Irish Christian Front

The Irish Christian Front (ICF) was a Catholic organisation that existed from August 1936 to October 1937. The organisation was founded with the intention of showing support and raising funds for the Nationalist faction of the Spanish Civil War. However, it quickly developed a domestic political agenda that was in opposition to the Irish government of the day. The ICF was able to send a substantial amount of money and supplies to the Nationalists but its domestic policies were never adopted.

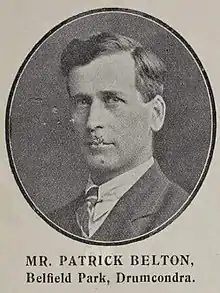

The ICF remains closely associated with its founder Patrick Belton, who was its president and leading figure. The Irish left accused Belton and the ICF of fascism. In response to these accusations Belton stated – ‘if it is necessary to be a fascist to defend Christianity then I am a fascist and so are my colleagues’.

Founding and early activities

The Spanish Civil War broke out in July 1936, as Spanish officers under Francisco Franco rebelled against the country's left-wing government. Sympathy for the rebellion was widespread in staunchly Catholic Ireland, as the rebels were seen as protecting their country from godless communism. The Irish media, especially the Irish Independent newspaper, generally supported the rebel (‘Nationalist’) cause. The murders of over 6,000 clergy and Catholic laypeople were heavily reported on. The war was generally seen as a religious, rather than a political conflict.[1]

It was in this context that the Irish Christian Front was set up. The ICF has been described as ‘the most significant manifestation of the widespread support for Franco’ in Ireland.[2] The group was established following a call by the Irish Independent on 22 August for the formation of a committee to help co-ordinate Irish support for the Nationalist cause. The first meeting of the ICF was on 31 August in the Mansion House in Dublin. The meeting was addressed by Alfie Byrne, the Lord Mayor of Dublin.[3] Branches were soon formed throughout the country, often spontaneously. The ICF was strongest in Leinster. Belton, a sitting TD for Cumann na nGaedheal, was the first and only president of the ICF and its leading figure. Former Cumann na nGaedheal TD Alexander McCabe served as secretary. American activist Aileen O'Brien served as Organizing Secretary and, later, the group's representative in Spain. Future Clann na Poblachta TD (and later Labour party member) Joseph Brennan served as vice-president.

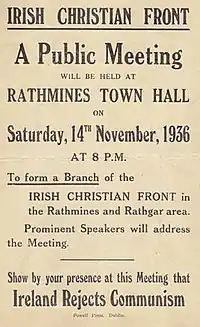

The ICF claimed that it was non-sectarian, to build up its support base.[4] It also claimed to be non-political, interested only in helping the church in Spain and not partisan politics.[5] The goals at this stage were to demonstrate Irish support for the Nationalists and raise funds.[6] A series of ‘monster’ rallies was held throughout the country. The first rally attracted over 15,000.[7] Another public meeting held in Cork in September attracted over 40,000.[8] Politicians of all major parties spoke at these meetings as did leading trade unionists, clergymen, academics and journalists.[9] Fights between the crowds and left-wing hecklers were not unknown.[10]

In opposition

The ICF's claim to be non-political quickly proved to be a sham, as by September the group was already petitioning the Fianna Fáil government of Éamon de Valera to officially recognise the Nationalist government as the legitimate government of Spain. This was contradictory to de Valera's policy of neutrality. Despite persistence, and the drafting of the ‘Clonmel Resolution’, which was affirmed by a number of local councils, the government did not budge and it passed the Spanish Civil War (Non-intervention) Bill in February 1937, which re-affirmed Irish neutrality. Belton was later to claim that 'the sympathies of the Fianna Fáil party are entirely with the Red Government in Spain.'[11]

The ICF also furthered a political agenda that was not directly related to Spain. This became increasingly important. The ICF called on the government to ban communism.[12] It called for the implementation of ‘a social policy based on the Papal encyclicals’.[13] More specifically, it advocated strict censorship of books and films that were ‘in any way subversive to the morals of the people’, youth in particular.[14] It campaigned to close down ‘nudist clubs’.[15] The ICF campaigned for the implementation of economic policies based on Catholicism.[16] As with many far-right organisations in Europe, it advocated corporatism.[17]

Anti-Semitism was increasingly a feature of the ICF. It campaigned against Jewish immigration to Ireland.[18] The supposed link between communism and Jews was heavily emphasised by speakers at ICF rallies. Speakers also expressed support and admiration for the policies of Adolf Hitler in Germany and Benito Mussolini in Italy.[19]

Decline and dissolution

The ICF raised over £30,000 for the Nationalists in Spain.[20] Medical supplies were sent, including ambulances. The Nationalists acknowledged the support given to them by the ICF.

The ICF failed to use Irish support for Franco to get right-wing social and economic policy implemented at home. One reason is the direction that war in Spain took. The murders of Spanish clergy did not persist beyond mid-1936. As Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy became involved, it became difficult to argue that conflict was a purely religious one.[21] Atrocities such as the bombing of Guernica also undermined the argument that the Nationalists were the more morally correct side.[22] The Irish people became less enthusiastic about Franco, and therefore the ICF.[23]

Corporatism and opposition to democracy were not popular ideas in Ireland, and the leadership in Dublin was not able to convert provincial branches to the cause, let alone the wider public.[24] Divisions on this were exacerbated over accusations that Belton had benefited personally from funds raised for Franco.[25] Despite extensive refutation by Belton of these suggestions, senior politicians and clergy distanced themselves from Belton and his organisation, further undermining its credibility.[26] Belton himself lost his seat in the July 1937 election, running on a theme of anti-communism.

Division between the Dublin leadership and provincial branches over the political direction of the organisation and accusations of corruption resulted in many branches closing in 1937. The national organisation was dissolved in October of that year.[27]

Standing Committee

- Patrick Belton (President)

- Dr James P. Brennan (Vice-President)

- Aileen O'Brien (Organizing Secretary)

- Alexander McCabe (Secretary)

- Liam Breen[28]

References

- Fearghal McGarry (2001) 'Ireland and the Spanish Civil War' in History Ireland Issue 3, Volume 9.

- McGarry (2001).

- Fallon (2014) 'All's Loud on the Christian Front'. .

- Martin White (2004). 'The Greenshirts: Fascism in the Irish Free State, 1935 – 45'. Queen Mary University of London PHD thesis. Available here: . p. 239.

- White (2004), p. 239.

- McGarry (2001).

- White (2004), p. 240.

- McGarry (2001).

- McGarry (2001).

- McGarry (2001).

- White (2004), p. 240.

- Fallon (2014).

- J. Bowyer Bell (1987). The Gun in Irish Politics: An Analysis of Irish Political Conflict, 1916 – 1986. London: Transaction Publishers. pp. 83–83.

- "Irish News reports on Spain - Jan- June 1937".

- Quoted in Fallon (2014).

- White (2004), p. 241.

- White (2004), p. 241.

- Fallon (2014).

- White (2004), pp. 241–42.

- White (2004), p. 243.

- McGarry (2001).

- Barry McLoughlin (2014). Fighting for Republican Spain, 1936–38: Frank Ryan and the Volunteers from Limerick in the International Brigades. P. 25.

- McGarry (2001).

- White (2004), p. 244.

- McLoughlin (2014), p. 25.

- White (2004), p. 242.

- White (2004), p. 244.

- White (2004), p.239.

.jpg.webp)