Irish clans

Irish clans are traditional kinship groups sharing a common surname and heritage and existing in a lineage-based society, originating prior to the 17th century.[1] A clan (or fine in Irish, plural finte) included the chief and his patrilineal relatives;[2] however, Irish clans also included unrelated clients of the chief.[3]

History

The Irish word clann is a borrowing from the Latin planta, meaning 'a plant, an offshoot, offspring, a single child or children, by extension race or descendants'.[4] For instance, the O'Daly family were poetically known as Clann Dalaigh, from a remote ancestor called Dalach.[4]

Clann was used in the later Middle Ages to provide a plural for surnames beginning with Mac meaning 'son of'.[4] For example, "Clann Cárthaigh" meant the men of the MacCarthy family and "Clann Suibhne" meant the men of the MacSweeny family.[4] Clann was also used to denote a subgroup within a wider surname, the descendants of a recent common ancestor, such as the Clann Aodha Buidhe or the O'Neills of Clandeboy, whose ancestor was Aodh Buidhe who died in 1298.[4] Such a "clan", if sufficiently closely related, could have common interests in landownership, but any political power wielded by their chief was territorially based.[4]

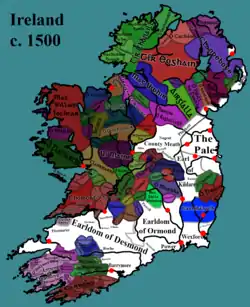

From ancient times, Irish society was organised around traditional kinship groups or clans. These clans traced their origins to larger pre-surname population groupings or clans such as Uí Briúin in Connacht, Eóganachta and Dál gCais in Munster, Uí Neill in Ulster, and Fir Domnann in Leinster.[5] Within these larger groupings there tended to be one sept (division) who through war and politics became more powerful than others for a period of time and the leaders of some were accorded the status of royalty in Gaelic Ireland. Some of the more important septs to achieve this power were Ó Conor in Connacht, MacCarthy of Desmond and Ó Brien of Thomond in Munster, Ó Neill of Clandeboy in Ulster, and MacMorrough Kavanagh in Leinster.

The largely symbolic role of high king of Ireland tended to rotate among the leaders of these royal clans.[6] The larger or more important clans were led by a taoiseach or chief who had the status of royalty and the smaller and more dependent clans were led by chieftains. Under brehon law, the leaders of Irish clans were appointed by their kinsmen as custodians of the clan and were responsible for maintaining and protecting their clan and its property. The clan system formed the basis of society up to the 17th century.[7]

"Clan" or "sept"

Scholars sometimes disagree about whether it is better to use the terms family, clan, or sept when referring to traditional Irish family groups. Historically, the term sept was not used in Ireland until the nineteenth century, long after the disfranchisement of much of the native Gaelic aristocracy. It is often argued that the English word 'sept' is most accurate referring to a sub-group within a large family, especially when that group has taken up residence outside of their family's original territory (O'Neill, MacSweeney, and O'Connor are examples); or if the branch of a name is substantially large enough or has a different surname (for example, Costigan and O’Dunphy are septs of the larger Fitzpatrick clan). Related Irish families or clans often belong to even larger groups, sometimes called tribes, such as the Dál gCais, Uí Néill, Uí Fiachrach, and Uí Maine. More recently, Edward MacLysaght suggested the English word sept be used in place of the word clan with regards to the historical social structure in Ireland, so as to differentiate it from the centralised Scottish clan system.[1] This would imply that Ireland possessed no formalised clan system, which is not wholly accurate. Brehon Law, the ancient legal system of Ireland clearly defined the clan system in pre-Norman Ireland, which collapsed after the Tudor Conquest. The Irish, when speaking of themselves, employed their term clan[n] which means 'children of the family' in Irish, though in Northern Irish the word has come to mean 'family'; this latter is teaghlach in Standard Irish, in the other Irish dialects, and in Scotland.

The end of the clan system

In the 16th century, English common law was introduced throughout Ireland, along with a centralised royal administration in which the county and the sheriff replaced the "country" and the clan chief.[8]

When the Kingdom of Ireland was created in 1541, the Dublin administration wanted to involve the Gaelic chiefs into the new entity, creating new titles for them such as the Baron Upper Ossory, Earl of Tyrone, and Baron Inchiquin. In the process, they were granted new coats of arms from 1552. The associated policy of surrender and regrant involved a change to succession to a title by the European system of primogeniture, and not by the Irish tanistry, where a group of male cousins of a chief were eligible to succeed by election. This change to the inheritance system was also taken up by the Scottish clans in the 17th and 18th centuries.

The early 17th century was a watershed in Ireland. It marked the destruction of Ireland's ancient Gaelic aristocracy following the Tudor re-conquest and cleared the way for the Plantation of Ulster.[9] In 1607 the senior Gaelic chiefs of Ulster left Ireland to recruit support in Spain but failed, and instead eventually arrived in Rome where they remained for the rest of their lives . After this point, the English authorities in Dublin established real control over all of Ireland for the first time, bringing a centralised government to the entire island, and successfully disarmed the native clans and their lordships.[10]

Later developments and "revival"

The first modern Irish clan societies were reformed in the latter half of the 20th century. Today, such groups are organised in Ireland and in many other parts of the world. Many independent Irish clan societies have sprung up with international affiliation and membership from across the global Irish diaspora for the purposes of helping others with preserving history, culture, and the pursuit of genealogy.[11] In 1989, the private organisation Clans of Ireland was formed under the leadership of Rory O'Connor, "Chieftain" of the "O'Connor Kerry Clan", with the purpose of creating and maintaining a Register of Clans, which can be consulted on the organisation's website.

See also

References

- Nicholls, 2003: pp. 8–11.

- Aitchison, N. B. (1994). "Kingship, Society, and Sacrality: Rank, Power, and Ideology in Early Medieval Ireland". Traditio. 49: 46. doi:10.1017/S036215290001299X.

- Bhreathnach, Edel (2014). Ireland in the medieval world, AD 400–1000: Landscape, kingship and religion. Four Courts Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-1846823428.

- Connolly, S. J., ed. (2007). Oxford Companion to Irish History. Oxford University Press. pp. 101–102. ISBN 978-0-19-923483-7.

- Ó Muraíle, 2003.

- Curley, 2004.

- Duggan, Catherine (2013). "14: End of the Brehon Era". The Lost Laws of Ireland. 13 Upper Baggot Street, Dublin: Glasnevin Publishing. p. 116. ISBN 9781908689214.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Connolly, S. J., ed. (2007). Oxford Companion to Irish History. Oxford University Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-19-923483-7.

- Curley, 2004

- Duggan, Catherine (2013). "14: End of the Brehon Era". The Lost Laws of Ireland. 13 Upper Baggot Street, Dublin: Glasnevin Publishing. pp. 122–124. ISBN 9781908689214.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - "The Fitzpatrick – Mac Giolla Phádraig Clan Society – Fitzpatrick clan genealogy, history, heraldry, tartans, gatherings, DNA, and research".

Sources

- Nicholls, K. (2003). Gaelic and Gaelicized Ireland in the Middle Ages, 2nd ed. Dublin: Lilliput Press.

- Curley, W. J. P. (2004). Vanishing Kingdoms: The Irish Chiefs and their Families. Dublin: Lilliput Press.

- Mac Fhirbhisigh, Dubhaltach (2004) [Written from original manuscript Leabhar na nGenealach which was written 1649-1650]. Ó Muraíle, Nollaig (ed.). The Great Book of Irish Genealogies. Dublin: De Burca Books. ISBN 0946130361.