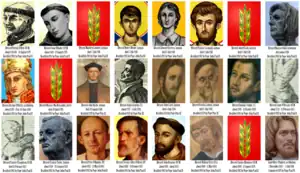

Irish Catholic Martyrs

Irish Catholic Martyrs (Irish: Mairtírigh Chaitliceacha na hÉireann) were 24 Irish men and women who have been beatified or canonized for dying for their Catholic faith between 1537 and 1681 in Ireland. The canonisation of Oliver Plunkett in 1975 brought an awareness of the others who died for the Catholic faith in the 16th and 17th centuries. On 22 September 1992 Pope John Paul II proclaimed a representative group from Ireland as martyrs and beatified them.

| Irish Catholic Martyrs | |

|---|---|

Irish Catholic Martyrs formally recognized | |

| Born | Ireland |

| Died | between 1537 (Venerable John Travers) – 1 July 1681 (Saint Oliver Plunkett), Ireland, England, Wales |

| Martyred by | Monarchy of England |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church |

| Beatified | 3 were beatified on 15 December 1929 by Pope Pius XI 1 was beatified on 22 November 1987 by Pope John Paul II 18 were beatified on 27 September 1992 by Pope John Paul II |

| Canonized | 1 (Oliver Plunkett) was canonized on 12 October 1975 by Pope Paul VI |

| Feast | 20 June, various for individual martyrs |

Canonized Martyrs

12 October 1975 by Pope Paul VI.

- Oliver Plunkett, Archbishop of Armagh, 1 July 1681 at Tyburn, London; beatified 1920

The 5 Irish Martyrs of England and Wales

15 December 1929 by Pope Pius XI.

- John Carey (alias Terence Carey) and Patrick Salmon, laymen, 4 July 1594 at Dorchester, England

- John Cornelius (Irish: Seán Conchobhar Ó Mathghamhna), Jesuit priest, 4 July 1594 at Dorchester, England

- John Roche, layman, 30 August 1588 at Tyburn, England

22 November 1987 by Pope John Paul II.

- Charles Mahoney (alias Meehan), Franciscan, 21 August 1679, Ruthin, Wales

The 17 Blessed Irish Martyrs

27 September 1992 by Pope John Paul II.

- Patrick O'Hely (Irish: Pádraig Ó hÉilí), Franciscan Bishop of Mayo, betrayed to Lord President of Munster Sir William Drury by the Rebel Earl and Countess of Desmond and executed at Kilmallock 13 August 1579

- Conn O'Rourke (Irish: Conn Ó Ruairc), Franciscan Friar, betrayed to the priest hunters by the Rebel Earl and Countess of Desmond and executed at Kilmallock, 13 August 1579

- Wexford Martyrs, 5 July 1581: Matthew Lambert, Robert Myler, Edward Cheevers, Patrick Cavanagh (Irish: Pádraigh Caomhánach), John O'Lahy, and one other unknown individual

- Margaret Ball, 1584, Dublin [1]

- Dermot O'Hurley ((Irish: Diarmaid Ó hUrthuile), Archbishop of Cashel, 20 June 1584

- Muiris Mac Ionrachtaigh (Maurice MacKenraghty), Chaplain to the Rebel Earl of Desmond, executed at Clonmel, during the Second Desmond Rebellion, 1585

- Dominic Collins, Jesuit lay brother executed without trial at Youghal, County Cork, 31 October 1602[2]

- Concobhar Ó Duibheannaigh (Conor O'Devany), Franciscan Bishop of Down & Connor, 11 February 1612

- Patrick O'Loughran, priest from County Tyrone and former spiritual director to Aodh Mór Ó Néill, 11 February 1612

- Francis Taylor, former Lord Mayor of Dublin, 1621

- Peter O'Higgins OP, Prior of Naas, 23 March 1642[3]

- Terence O'Brien OP, Bishop of Emly, 31 October 1651

- John Kearney, Franciscan Prior of Cashel, 1653[4]

- William Tirry (Irish: Liam Tuiridh), Augustinian Friar from St. Austin's Abbey in Cork City, captured by the priest hunters at Fethard, County Tipperary and executed by hanging, officially for high treason against The Protectorate and Commonwealth of England, but in reality for remaining in Ireland and continuing his priestly ministry in nonviolent resistance of the regime's decree of banishment for all priests, at Clonmel, County Tipperary, 12 May 1654

The 42 Irish Martyrs

_(14594645478).jpg.webp)

A group of 42 Irish martyrs have been selected for canonisation. This group is composed mostly of priests, both secular and religious as well as several lay men and two lay women. These martyrs have not yet been beatified.

- Edmund Daniel, SJ, 25 October 1572 in Cork

- Teige O'Daly, OFM, about March 1578 in Limerick

- Donal O'Neylan, OFM, 28 March 1580 in Youghal, Cork

- Gelasius Ó Cuileanáin (born 1554), Cistercian Abbot of Boyle, 21 November 1580 in Dublin

- Eoin O'Mulkern, OPraem, 21 November 1580 in Dublin

- David, John Sutton and Robert Scurlock, laymen, 13 November 1581 in Dublin

- Maurice, Thomas, and Christopher Eustace, laymen, 13 November 1581 in Dublin

- William Wogan and Robert Fitzgerald, laymen, 13 November 1581 in Dublin

- Felim O'Hara, OFM, 1 May 1582 in Moyne, Cork

- Walter Eustace, layman, 14 June 1583 in Dublin

- Richard Creagh (born 1523), Archbishop of Armagh, late 1586 in London, England

- Brian O'Carolan, priest, 24 March 1606 near Trim, Meath

- John Burke, layman, 20 December 1606 in Limerick

- Donough MacCready, priest, before 05 August 1608 in Coleraine, Northern Ireland

- George Halley (born 1622), OCD, 15 August 1642 in Siddan, Meath

- Theobald and Edward Stapleton, priests, 13 September 1647 in Cashel, Tipperary

- Thomas Morissey, priest, 13 September 1647 in Cashel, Tipperary

- Richard Barry, OP, 13 September 1647 in Cashel, Tipperary

- Richard Butler and James Saul, OFM, 13 September 1647 in Cashel, Tipperary

- William Boyton, SJ, 13 September 1647 in Cashel, Tipperary

- Elizabeth Kearney (mother of Blessed John Kearney) and Margaret (surname unrecorded), laywomen, 13 September 1647 in Cashel, Tipperary

- John Bathe, SJ and Thomas Bathe, priest, 11 September 1649 in Drogheda, Louth

- Peter Taafe, OSA,11 September 1649 in Drogheda, Louth

- Dominic Dillon and Richard Oveton, OP, 11 September 1649 in Drogheda, Louth

- Laurence and Bernard O'Ferrall, OP, between February-March 1649 in Longford

- Conor MacCarthy, priest, 5 June 1653 in Killarney, Kerry

- Francis O'Sullivan, OFM, 23 June 1653 on Scarrrif Island, Kerry

- Thaddeus Moriarty, OP, 15 October 1653 in Killarney, Kerry

- Donal Breen and James Murphy, priests, 14 April 1655 in Wexford

- Luke Bergin, OP, 14 April 1655 in Wexford

The 2 Irish Capuchin Martyrs

The cause of canonisation of these two Irish capuchins has also been opened:

- John Tobin (born 1620), OFMCap, 6 March 1656 in Waterford

- James Dowdall (born 1626), OFMCap, 20 February 1710 in London, England

History

The persecution of Catholics in Ireland in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries came in waves, caused by a reaction to particular incidents or circumstances, with intervals of comparative respite in between.[5]

Henry VIII

Religious persecution of Catholics in Ireland began under King Henry VIII (then Lord of Ireland) after his excommunication in 1533. The Irish Parliament adopted the Acts of Supremacy, which declared the Irish Church subservient to the State.[6] In response, Irish priests, bishops, and those who continued to pray for the pope during Mass were tortured and killed.[7] The Treasons Act 1534 defined even unspoken mental allegiance to the Holy See as high treason. Many were imprisoned on this basis. Alleged traitors who were brought to trial, like all other British subjects tried for the same offence prior to the Treason Act 1695, were forbidden the services of a defence counsel and forced to act as their own attorneys.[8]

In 1536, Fr. Charles Reynolds was posthumously convicted of high treason for successfully persuading the Pope to excommunicate Henry VIII of England. In 1537, John Travers, the Chancellor of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin, was executed under the Act of Supremacy.[9]

Elizabeth I

Relations improved after the accession of the Catholic Queen Mary in 1553–58, and in the early years of the reign of her sister Queen Elizabeth I. After Mary's death in November 1558, Elizabeth's Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy of 1559, which re-established the Church of England's separation from the Catholic Church. Initially, Elizabeth adopted a moderate religious policy. The Acts of Supremacy and Uniformity (1559), the Prayer Book of 1559, and the Thirty-Nine Articles (1563) were all Protestant in doctrine, but preserved many traditionally Catholic ceremonies.[10]

In 1563 the Earl of Essex issued a proclamation, by which all Roman Catholic priests, secular and regular, were forbidden to officiate, or even to reside in Dublin or in The Pale. Fines and penalties were strictly enforced for Recusancy from the Anglican Sunday service; before long, torture and death were inflicted. Priests and religious were, as might be expected, the first victims. They were hunted into the Mass rocks in mountains and caves; and the parish churches and few monastic chapels which had escaped the rapacity of Henry VIII were also destroyed.[11]

During the early years of her reign no great pressure was put on Catholics to conform to the "Established Church" of the new regime, but the situation changed rapidly from about 1570 onwards, mainly as a result of Pope Pius V's papal bull Regnans in Excelsis which "released [Elizabeth I's] subjects from their allegiance to her".[5]

In Ireland the First Desmond Rebellion was launched in 1569, at almost the same time as the Northern Rebellion in England. The Wexford Martyrs were found guilty of high treason for aiding in the escape of James Eustace, 3rd Viscount Baltinglass and refusing to take the Oath of Supremacy and declare Elizabeth I of England to be the Supreme Head of the Church of England and Ireland.

Charles II

During this period, the English treatment of Catholics in Ireland was more lenient than usual, owing to the sympathy of the king, until the Popish Plot, a conspiracy theory concocted by Titus Oates, between 1678 and 1681 gripped the Kingdoms of England and Scotland in anti-Catholic hysteria. Those caught up in the false allegations included:

- Peter Talbot, Archbishop of Dublin (died in prison, November 1680)

- Oliver Plunkett, Archbishop of Armagh, executed at Tyburn 1 July 1681

As persecution of Catholics heated up in reaction to the Titus Oates plot, a priest named Father Mac Aidghalle was murdered while saying the Tridentine Mass at a Mass rock that still stands atop Slieve Gullion. The perpetrators were a band of redcoats under the command of a priest hunter named Turner. Local Rapparee leader Count Redmond O'Hanlon is said in local oral tradition to have avenged the murdered priest and in so doing to have sealed his own fate.[12]

Investigations

Irish martyrs suffered over several reigns. There was a long delay in starting the investigations into the causes of the Irish martrys for fear of reprisals. Further complicating the investigation is that the records of these martyrs were destroyed, or not compiled, due to the danger of keeping such evidence. Details of their endurance in most cases have been lost.[6] The first general catalog is that of Father John Houling, SJ, compiled in Portugal between 1588 and 1599. It is styled a very brief abstract of certain persons whom it commemorates as sufferers for the Faith under Elizabeth.[7]

After Catholic Emancipation in 1829, the cause for Oliver Plunkett was re-visited. As a result, a series of publications on the whole period of persecutions was made. The first to complete the process was Oliver Plunkett, Archbishop of Armagh, canonized in 1975 by Pope Paul VI.[6] Plunkett was certainly targeted by the administration and unfairly tried.

Biographies

John Kearney, OFM

John Kearney (1619-1653) was born in Cashel, County Tipperary and joined the Franciscans at the Kilkenny friary. After his novitiate, he went to Leuven in Belgium and was ordained in Brussels in 1642. Returned to Ireland, he taught in Cashel and Waterford, and was much admired for his preaching. In 1650 he became erenagh of Carrick-on-Suir, County Tipperary. During the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, he was arrested by the New Model Army and hanged at Clonmel, County Tipperary. He lies buried in the chapter hall of the suppressed friary of Cashel.[4]

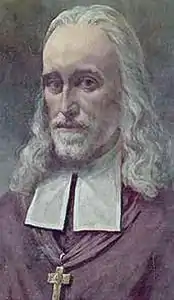

Peter O'Higgins OP

Peter O'Higgins was born in Dublin around 1602 during the persecution under James I. He was educated secretly in Ireland and later in Spain. With the accession of Charles I in 1625, a limited tolerance obtained and Peter came back to Dublin and was sent to re-open the Dominican house in Naas, supported by the Viceroy Strafford who was building Jigginstown nearby. The 1641 rebellion, a result of the plantations, evictions and persecutions (but not in County Kildare), brought with it years of conflict between Gaels vs Hiberno-Normans, Catholics vs Protestants; Puritans vs Anglicans. During this time Dr. William Pilsworth, Protestant Vicar of Donadea, was arrested by rebel soldiers and was about to be hanged, when Fr. Peter O'Higgins stepped forward. Dr. Pilsworth later wrote that when he was on the gallows, "a priest whom I never saw before, made a long speech on my behalf saying that this…was a bloody inhuman act that would…draw God's vengeance on them. Whereupon I was brought down and released."[3]

The Irish Royal Army moved on Naas in February 1642 and O'Higgins was arrested and turned over to Sir Charles Coote, Governor of Dublin. O'Higgins was offered his life if he would renounce his faith. He responded, "So here the condition on which I am granted my life. They want me to deny my religion. I spurn their offer. I die a Catholic and a Dominican priest. I forgive from my heart all who have conspired to bring about my death." Among the crowd at the foot of the scaffold was Dr. William Pilsworth who shouted out: "This man is innocent. This man is innocent. He saved my life." Dr. William Pilsworth was not wanting in courage, but his words fell on deaf ears. With the words "Deo Gratias" on his lips Peter O'Higgins died on 23 March 1642.[3]

The most likely reason for Prior Higgins' execution without trial was that on the previous day, 22 March, at a synod at Kells, County Meath chaired by Archbishop Hugh O'Reilly, the Catholic bishops had pronounced the rebellion to be a "Holy and Just War". Higgins had been summarily executed as a result.[13]

Legacy

Various churches have been dedicated to the martyrs, including:

- Church of the Irish Martyrs, Ballyraine, Letterkenny[1]

- Church of the Irish Martyrs, Ballycane, Naas[14]

- Church of the Irish Martyrs, Cromwell, Otago, New Zealand.

- Church of the Irish Martyrs, Mallee Border Parish, Lameroo, South Australia, Australia

- Chapel of the Irish Martyrs, Pontificio Collegio Irlandese, Pontifical Irish College, Rome, Italy.

See also

References

- ""The Irish Martyrs", The Church of the Irish Martyrs, Ballyraine". Archived from the original on 2013-09-24. Retrieved 2013-04-13.

- "Archives".

- "Peter O'Higgins OP". Newbridge College.

- "Franciscan Saints & Blessed". Archived from the original on 2014-02-04.

- Barry, Patrick, "The Penal Laws", L'Osservatore Romano, p.8, 30 November 1987

- "The Irish Martyrs", Irish Jesuits, sacredspace.ie; accessed 16 December 2015.

- "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Irish Confessors and Martyrs".

- Hale's History of Pleas of the Crown (1800 ed.) vol. 1, chapter XXIX (from Google Books).

- "Martyrs of England and Wales" New Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9 (1967), p. 322.

- "The Reign of Elizabeth I" Archived 2017-05-09 at the Wayback Machine by J.P. Sommerville, University of Wisconsin.

- Cusack, Margaret Anne, An Illustrated History of Ireland, libraryireland.com; accessed 11 July 2015.

- Tony Nugent (2013), Were You at the Rock? The History of Mass Rocks in Ireland, pages 80–81.

- Catholic encyclopedia article, accessed Feb 2017

- "Naas Parish website". Archived from the original on 2007-11-23. Retrieved 2008-01-29.

Sources

- New Catholic Dictionary: Irish Martyrs