Irish soviets

The Irish soviets (Irish: Sóivéidí na hÉireann) were a series of self-declared soviets that formed in Ireland during the revolutionary period of the Irish War of Independence and the Irish Civil War (1919 to 1923), mainly in the province of Munster. "Soviet" in this context refers to a council of workers who control their place of work, not a Soviet state.

Background

The labour movement in Ireland during the Irish War of Independence had been deeply affected by the events of the Dublin Lockout of 1913 as well as Bolshevik Revolution in Russia in 1917. It was also being influenced by the concurrent Revolutions of 1917–1923, which saw several left-wing led revolutions rise up in Europe, also inspired by the revolution in Russia. Soviets were emerging across Europe in places such as Bavaria, Bremen, Ukraine and Hungary. This trend caught on in Ireland as well, itself in the midst of a revolution as the Irish Republican Army sought to end British rule over Ireland.[1][2][3]

The first soviet - Monaghan Asylum

Preceding the more famous Limerick Soviet by two months, the first Irish soviet was declared on 29 January 1919. Lead by Donegal union organiser and IRA Commander Peadar O'Donnell, the soviet was declared as part of a strike for better working conditions for the staff of the Monaghan Lunatic Asylum (as it was then known). Amongst the worker's complaints were that they were being forced to work 93 hours a week and were not allowed to leave the premises between shifts. Upon declaration of the soviet, a red flag was flown over the building. In response armed police were sent to remove the workers, however, they had barricaded themselves inside. The operators of the Asylum were forced to negotiate with the workers. Workers won a 56-hour week and a pay rise for both male and female staff. A further concession was that married staff were to be allowed go home after their shifts ended. The Asylum is still in operation today as St. Davnet's Hospital.[4][5] It was eventually disestablished on 4 February of the same year.

Limerick Soviet

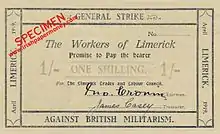

One of the first and most important soviets to be declared in Ireland at this time was the soviet declared in Limerick City from 14 to 27 April 1919.[6] Following IRA activity inside the city as well as the death of IRA member Robert Byrne, the Royal Irish Constabulary sought to lock down the city to prevent further encroachment by the revolutionaries. However, their implementation of the lockdown was overzealous and heavyhanded and resulted in a backlash from the inhabitants of the city. A strike committee was created by Trade Unionists inside Limerick and they declared a general strike against "British Military Occupation". For two weeks all British troops were boycotted and the special strike committee organised the printing of their own money, control over food prices and the publishing of newspapers.[2]

Subsequent soviets

Knocklong Soviet

The soviet in Limerick City was the most significant soviet to be declared owing to the fact it had the largest number of participants, but many more followed in its wake. The following month on 15 May 1920, workers in County Limerick began seizing creameries belonging to the Cleeve Family Business, the primary one being located near the village of Knocklong. The Cleeves were an Anglo-Canadian Unionist family committed to the British Empire, and a major business operator, employing over 3,000 workers across Ireland in dairy-related industries in addition to about 5,000 farmers.[7] During World War I they heavily promoted recruitment efforts by the British Army in Limerick. It was in their personal interest to do so, as the Cleeves were also profiting from the war as they were also supplying food to the British army, netting a profit around £1,000,000 from this contract by end of 1918.[8] The Cleeves' support for the British would have found them little support amidst the revolution in Ireland, but further compounding resentment against them was the fact that the Cleeves were considered to be one of the lowest paying employers in Ireland. The average unskilled labourer working for the Cleeves could only expect to be paid 17 shillings a week, an amount considered a pittance at the time.[2][9]

Following a trade dispute with the Cleeves, workers belonging to the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU) seized production facilities and began running them independently of the Cleeves. A red flag was flown over the main building and a banner reading "KNOCKLONG SOVIET CREAMERY: WE MAKE BUTTER NOT PROFITS" was displayed. Work continued as per usual at the creameries but the Cleeves were forced to negotiate with the workers in order to regain control of the facilities. After five days of occupation, the workers were able to force the Cleeves to agree to a wage increase, a 48-hour work week, the introduction of 14 holiday days per year, and the improvement of ventilation systems across the workspaces.

The success of the Knocklong Soviet would result in both further strikes against Cleeves' owned premises but also retaliation from the Cleeves. At first, the Cleeves attempted to lay off workers at Knocklong under the auspices that a national general strike by ITGWU against handling British munitions had resulted in "a lack of work". However, this ploy was defeated by the formation of a strike committee. The Cleeves quickly changed tack; On the 24th of August, they insured the creamery against the outbreak of a fire. Coincidentally on the 26th of August, a unit of Black and Tans arrived in Knocklong and burnt down the creamery.[8]

Waterford Soviet

One of the shorter-lived but nonetheless influential soviets arose in April 1920 in Waterford City. The soviet existed during a national general strike against the detention of Republicans on hunger-strike. Workers enforced the general strike as well as a permit system. After a number of days, word came to Waterford that the general strike had been a success and the British government had caved in to the demand. Thousands flocked to the City Hall where, before Amhrán na bhFiann was sung to close out the event, Union leaders sang the verses of The Red Flag while a crowd less familiar with the song piped in on the choruses.[10]

Within Ireland, the Waterford did not draw much comment. The reason for this was partly because nationalists had no wish to fuel loyalist propaganda that Sinn Féin was really ‘Bolshevist’, partly because ‘red flaggery’ was no longer a novelty in Ireland, and partly because the ‘soviets’ did not offer any immediate threat to class relations; none of them attempted to change the social order, and the status quo ante resumed with the termination of the strike. The Irish Labour Party similar shied away from the topic; the party was emerging as a Reformist party and was steering away from encouraging or discussing militant socialist tactics.[10]

In Britain however, the press showed a much greater interest. On 27 April, an article headed " 'Soviet' Government in Waterford" graced the Guardian and asserted that a group of southern loyalists had given Bonar Law a ‘full account’ of events in the city. They reported that Waterford been ‘taken over by a Soviet Commissioner and three associates’. On 24 and 28 April, the British Labour paper, the Daily Herald, carried articles on Waterford's ‘Red Guards’, stating that a red flag floated over the Town Hall, and a sort of ‘Red Guard’ was established under three transport leaders and gave the impression that the city was undisputedly ruled by a soviet during the time of the strike.[10]

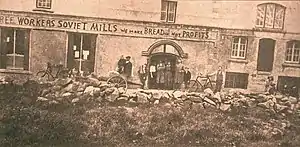

Bruree Soviet

On 26 August 1921, the bakery and mills in Bruree, County Limerick (owned by the Cleeve Family) were occupied by almost all of its employees save the manager and a clerk. The workers raised a red flag, raised a banner reading "Bruree Soviet Workers Mill" and proclaimed they were now in control of the mill and would be selling its food at a lower price, forgoing the "profiteering" formerly being practised there. Forcing the owners to the negotiation table at Liberty Hall in Dublin, Union officials claimed the soviet was able to drop prices, double sales and increase wages.[11] Sinn Féin's Minister for Labour Countess Markievicz mediated the negotiations and it is alleged she threatened to send in IRA troops to the Bruree Soviet if they did not accept the outcome of the arbitration.[8]

Cork Harbour Soviet

In 1920 a commission in Cork City established by Lord Mayor Tomás Mac Curtain had been tasked with determining what the living wage of workers in Cork City should be. By late September 1920 it was reporting that this wage should be 70 shillings a week, an amount rather more than most workers in the city received at this time. The commission repeated their recommendation again in February 1921. It was at this point that the local ITGWU branch asked the Cork Harbour Board to make 70 shillings the wage for workers. The Cork Harbour Board resisted for months and by June 1921 had firmly rejected the proposal. The proposal was rejected a final time in September 1921. In response, workers seized control of the Cork Custom House, a red flag was flown and a soviet declared on 7 September.[12] News of the Cork Harbour Soviet was covered in media as far away as the New York Times.[13] Locally, the Unionist aligned paper The Irish Times decried the Cork Harbour Soviet as an outbreak of "Irish Bolshevism" and fearfully pondered of the possibility of a civil war between Nationalists and Socialists breaking out if Ireland achieved independence from Britain.[13] Eventually, the Cork Harbour Soviet was disestablished after concluding with an agreement regarding an increase in wages.[14]

Other soviets

Between 1921 and 1923, other soviets were said to have arisen and seized North Cork railways, the mines at Arigna in County Roscommon (4 May 1921), the Drogheda Iron Foundry (September 1921), the quarry and the fishing boats at Castleconnell (November 1921), a coach builders in Tipperary as well as the local gas works (4 May 1922), a clothing factory in Dublin's Rathmines, sawmills in Killarney and Ballinacourtie (24 April 1922), the Ballingarry Coal Mines near Ballingarry, South Tipperary (24 April 1922), and the Waterford Gas Works (26 January 1923).[8] Furthermore, it is claimed there was a soviet in Broadford, County Clare (February 1922), while it is also claimed that the IRA was used to break up soviets in Whitechurch, County Dublin, Youghal and Fermoy.[3]

Fall of the soviets

As the revolutionary period in Ireland drew to a close, so too did the age of the soviets. The protracted conflict in Ireland was draining the economy and the ability of employers to meet wage demands and their ability to quickly end strikes by simply giving in to the workers' demands. In fact, falling prices caused by the conflict now saw employers seeking to cut wages. At the end of 1921 the Cleeves business empire declared that it was £100,000 in debt, and claimed to have taken roughly £275,000 in losses for the year. The soviets, having fought so hard to make the gains that they had, were not receptive to these claims. The two sides attempted to mediate but talks soon broke down. On 12 May 1922 The Cleeves declared a lockout, put 3,000 of its employees out of work. In response the soviets seized production centres in Bruff, Athlacca, Bruree, Tankardstown, Dromin and Ballingaddy near Kilmallock all in County Limerick, and centres in Tipperary Town, Galtymore, Bansha, Clonmel and Carrick-on-Suir in County Tipperary and finally Mallow in County Cork.[2]

The Irish Times denounced the seizures and declared that the workers had "neither allegiance to the Irish Free State nor the Irish Republic, but only to Soviet Russia". Trouble for the soviets was also brewing on another front: the farmers who supplied the creameries with milk were beginning to sour on their comrades. The Irish Farmers Union led a campaign to deny the soviets a supply of milk, and resolved to "forbid our members to supply under the Red Flag, which is the flag of Anarchy and revolution".[2]

The Civil War that erupted between those for and against the Anglo-Irish Treaty had seen Munster become a hotbed and base for the Anti-Treaty IRA forces, and thus a battleground to be fought over. The soviets came into conflict with both Anti-Treaty and the Free State National Army. The Tipperary Soviet was involved in a shoot out with the anti-treaty side. The gasworks in Tipperary was destroyed by the retreating anti-treaty forces.[3] Similarly the newly formed National Army also took to dismantling the soviets. Extreme pressure was being placed on the fledgeling Irish Free State by both the British Government and the wider world to maintain a conservative order in Ireland. The soviets were deemed agents of anarchy by both the conservative press and conservative politicians, and thus another element the National Army had to remove. Without a wider political structure or organisation to unify them, nor a fighting force to defend themselves, the soviets were forced to fold and bow out. When Free State forces entered any town that had a soviet, they would arrest the leaders and take down any symbols signalling defiance such as Red Flags.[2][15]

References

- Dorney, John (6 June 2013). "The General Strike and Irish independence". The Irish Story. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- Lee, D. (2003), "The Munster Soviets and the Fall of the House of Cleeve" (PDF), Made In Limerick, archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2019 [Accessed 30 Jan. 2019].

- Nielsen, Robert (8 October 2012). "Irish Soviets 1919-23". Whistling in the Wind. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- McNally, F. (2015). "Political asylum – An Irishman's Diary on mental health and the Monaghan Soviet". The Irish Times. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- "SF Councillor calls for the Monaghan Lunatic Asylum Soviet of 1919 to be commemorated". northernsound.ie. 4 June 2018. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- Patrick Smyth (21 January 2019). "When Limerick Workers Seized The City For Two Weeks". The Irish Times. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- O'Donoghue, Ciara (15 May 2017). "Cleeve's Condensed Milk Company, Limerick, and the Irish revolution". ul.ie. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- O'Connor Lysaght, D.R. (1981), "The Munster Soviet Creameries", Irish History Workshop, retrieved 31 January 2019

- "When the red flag flew over Munster". 6 November 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- O’Connor, Emmet (2000). "The Waterford Soviet: Fact or fancy?". historyireland.com. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- Nielsen, Robert (8 October 2012). "Irish Soviets 1919-23". Whistling in the Wind. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- "The Cork Harbour Soviet". Mother Jones. 5 May 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- "The Cork harbour strike of 1921". libcom.org. 21 February 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- "Did you know that 99 years ago this week in 1921, a Soviet took control of the docks in Cork City Ireland for seven days?". linkedin.com. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- D’Arcy, Ciarán (4 May 2015). "Red flag – An Irishman's Diary on the Irish soviets". The Irish Times. Retrieved 31 January 2019.