Isidore van Kinsbergen

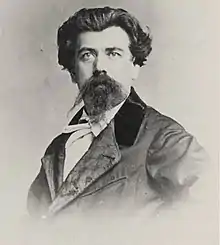

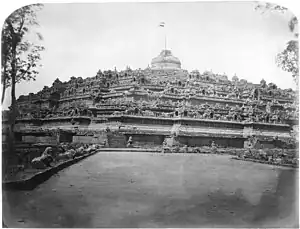

Isodorus "Isidore" van Kinsbergen (3 September 1821 – 10 September 1905) was a Dutch-Flemish engraver who took the first archaeological and cultural photographs of Java during the Dutch East Indies period in the nineteenth century. The photographs that he produced during his visit to the colony in 1851 ranged in subject from antiquities and landscapes to portraits, court-photography, model studies and nudes. His monograph was published in black and white with a coloured quire of nearly 400 photographs.[1] His photograph of Borobudur was the first picture of the monument that showed the results of the first restoration c. 1873.

Isidore van Kinsbergen | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Isodorus van Kinsbergen 3 September 1821 |

| Died | 10 September 1905 (aged 84) |

| Nationality | Dutch-Flemish |

| Known for | Engraving, photography |

Early life

Isidore van Kinsbergen was born in Bruges in 1821 (at that time, Bruges was part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands). Having studied painting and singing in Paris, he joined a French opera group that travelled to Batavia (the present day Jakarta) in 1851.[2] After several performances the group left the Dutch East Indies, but Van Kinsbergen decided to stay there. He became interested in the new medium of photography, particularly in using the albumen print technique. He opened the first albumen print processing shop in Batavia.

Commissions

In 1862, the General Secretary of East Indies Alexis Loudon invited van Kinsbergen to join the government mission to Siam (present day Thailand) in February 1862 to cover the 1860 Treaty of Friendship, Trade and Navigation between the Netherlands and Siam.[2] It was van Kinsbergen's first government assignment and he used the occasion to capture a number of curiosities in the country.

During that period, the Batavia Society of Arts and Sciences, whose main interests were in archaeological research and conservation, became interested in the newly invented albumen print medium. The society felt that the world should know more about Javanese culture as expressed in the old inscriptions, statues, customs and temples. The Society arranged an archaeological tour around Java, headed by J.F.G. Brumund, a priest of the Batavian Evangelic Community and a specialist in Javanese. The Society also commissioned van Kinsbergen to accompany Brumund during his tour in order to illustrate Brumund's publication of Javanese culture and antiquities.[2] The government granted permission for this tour, with the restriction that all wet-prints (cliches) would be government property and that extra printing would only be allowed with permission from the government.

As part of his contract with the Batavian Society, van Kinsbergen had to take photographs of Borobudur, which had just been cleaned and restored. However, when he went to photograph the Panataran Hindu temple complex in East Java in 1867, he ran out of chemicals. In his enthusiasm for photographing the many reliefs of the temple complex, he used up so many glass slides that he could not go to Borobudur as he had intended to.[2] The Society was nervous about van Kinsbergen's delay, so they did not grant his request to supply new slides.

However, van Kinsbergen's photographs satisfied the Society and he became renowned as "the Society's Photographer". His work on repairing the system for managing water flow during his trip in the Dieng Plateau in order to photograph the Javanese Hindu temple there was avidly praised by the Society. The board then decided that van Kinsbergen was no longer obliged to follow Brumund's directions, but should pursue his own vision.[2] Brumund published his work in 1868, but without the full illustrations of van Kinsbergen. Later in 1872, van Kinsbergen published photographs of monuments in Java, but he was criticized for missing some important ruins, for instance, those in the east of Kediri.[3]

Although Brumund's publication included drawings of Borobudur, the Batavia Society still felt that it was incomplete. In April 1873, van Kinsbergen set off to the monument. Cleaning, digging and other technical difficulties delayed his start in taking pictures until August that year. The wet monsoon season further hampered his work, resulting in a series of only 43 photographs taken between August and December. The Society was disappointed with the number of photographs, although satisfied with the printing and artistic quality.[2]

Photographic styles

Isidore van Kinsbergen was known as a perfectionist.[2] During his work in Borobudur, he selected the statues and panels which had been preserved best to take pictures of. He preferred a non-frontal angle, which shows a better depth of the relief and the skills of the relief maker. To stress its timeless beauty, van Kinsbergen blocked out the original background in the negative film instead of putting up a black curtain during photographing.

There are some criticisms of van Kinsbergen's photographs. He missed some details and sometimes his series was unbalanced. Trained as an artist, his works lacked archaeological descriptions, the main purpose of his contract. The printing quality, however, is beyond question and he had success showing the beauty of classical Javanese arts. His photographs were shown to the public both in the 1873 International Exhibition in Vienna and the 1878 World Exhibition in Paris.[2] His works can be seen in several places, including the National Museum in Amsterdam.

Gallery

Dutch naval officer at Batavia, Dutch East Indies

Dutch naval officer at Batavia, Dutch East Indies Dancers for the Sultan of Yogyakarta (circa 1866)

Dancers for the Sultan of Yogyakarta (circa 1866) Chinese locksmith in Batavia (1870)

Chinese locksmith in Batavia (1870) Balinese dancer at Singaraja

Balinese dancer at Singaraja Statuary from Buitenzorg (Bogor)

Statuary from Buitenzorg (Bogor) Local guards in Batavia

Local guards in Batavia Bronze items from a priest at "Kawali near Tjiamis"

Bronze items from a priest at "Kawali near Tjiamis" Sculptures at Gaprang in Kediri Kingdom

Sculptures at Gaprang in Kediri Kingdom Portrait of a woman in Batavia circa 1875

Portrait of a woman in Batavia circa 1875

References

- Theuns-de Boer, Gerda; Asser, Saskia & Wachlin, Steven (2005). Isidore van Kinsbergen 1821–1905: photo pioneer and theatre maker in the Dutch East Indies. Zaltbommel / Brill Academic. ISBN 978-9067182690.

- Theuns-de Boer, Gerda (March 2002). "Java through the Eyes of Van Kinsbergen" (PDF). The Newsletter. International Institute of Asian Studies (27): 32.

- Malkiel-Jirmounsky, Myron (1939). "The Study of The Artistic Antiquities of Dutch India". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. Harvard-Yenching Institute. 4 (1): 59–68. doi:10.2307/2717905. JSTOR 2717905.