Supreme Court of Israel

The Supreme Court of Israel (Hebrew: בֵּית הַמִּשְׁפָּט הָעֶלְיוֹן, Beit HaMishpat HaElyon; Arabic: المحكمة العليا, Al Mahkama Al ‘Ulyā) is the highest court in Israel. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all other courts, and in some cases original jurisdiction.

| Supreme Court of Israel | |

|---|---|

| Hebrew: בית המשפט העליון Arabic: المحكمة العليا | |

Emblem of Israel[1] | |

| |

| Established | 1948 |

| Location | Givat Ram, Jerusalem |

| Composition method | Presidential appointment upon nomination by the Judicial Selection Committee |

| Authorized by | Basic Laws of Israel |

| Number of positions | 15 |

| Website | https://supreme.court.gov.il |

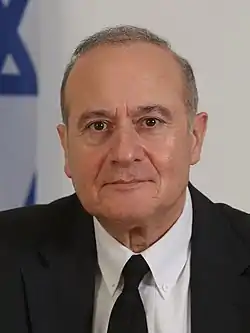

| President | |

| Currently | Uzi Vogelman (acting) |

| Since | 17 October 2023 |

| Lead position ends | TBD |

| Jurist term ends | 6 October 2024 |

| Deputy President | |

| Currently | Uzi Vogelman |

| Since | 9 May 2022 |

| Lead position ends | 6 October 2024 |

| Jurist term ends | 6 October 2024 |

The Supreme Court consists of 15 judges appointed by the President of Israel, upon nomination by the Judicial Selection Committee. Once appointed, Judges serve until retirement at the age of 70 unless they resign or are removed from office. The Presidency of the Supreme Court is currently vacant, following the retirement of Esther Hayut. As such, Deputy President Uzi Vogelman is serving as acting President. The Court is situated in Jerusalem's Givat Ram governmental campus, about half a kilometer from Israel's legislature, the Knesset.

When ruling as the High Court of Justice (Hebrew: בֵּית מִשְׁפָּט גָּבוֹהַּ לְצֶדֶק, Beit Mishpat Gavo'ah LeTzedek; also known as its acronym Bagatz, בג"ץ), the court rules on the legality of decisions of State authorities: government decisions, those of local authorities and other bodies and persons performing public functions under the law, and direct challenges to the constitutionality of laws enacted by the Knesset. The court may review actions by state authorities outside of Israel.

By the principle of binding precedent (stare decisis), Supreme Court rulings are binding upon every other court, except itself. Over the years, it has ruled on numerous sensitive issues, some of which relate to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, the rights of Arab citizens, and discrimination between Jewish groups in Israel.

On 24 July 2023, the 25th Knesset "passed the bill to cancel the reasonableness standard into law", which could diminish the power of the Supreme Court to check future actions of the government.[2]

Judicial appointments

.jpg.webp)

Supreme Court Judges are appointed by the President of Israel, from names submitted by the Judicial Selection Committee, which is composed of nine members: three Supreme Court Judges (including the President of the Supreme Court), two cabinet ministers (one of them being the Minister of Justice), two Knesset members, and two representatives of the Israel Bar Association. Appointing Supreme Court Judges requires a majority of 7 of the 9 committee members, or two less than the number present at the meeting.

All candidates for appointment to the Supreme Court must have a minimum of five years of experience as a district court judge or otherwise at least ten years of professional legal experience including a minimum of five years practicing law in Israel. These requirements may be waived for a person recognized as an "eminent jurist", although this special category has only been used once for an appointment.[3]

The three organs of state—the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government—as well as the bar association are represented in the Judges' Nominations Committee. Thus, the shaping of the judicial body, through the manner of judicial appointment, is carried out by all the authorities together.

Supreme Court Judges cannot be removed from office except by a decision of the Court of Discipline, consisting of judges appointed by the President of the Supreme Court, or upon a decision of the Judicial Selection Committee—at the proposal of the Minister of Justice or the President of the Supreme Court—with the agreement of seven of its nine members.[4]

The following are qualified to be appointed Judge of the Supreme Court: a person who has held office as a judge of a District Court for a period of five years, or a person who is inscribed, or entitled to be inscribed, in the roll of advocates, and has for not less than ten years –continuously or intermittently, and of which five years at least in Israel – been engaged in the profession of an advocate, served in a judicial capacity or other legal function in the service of the State of Israel or other service as designated in regulations in this regard, or has taught law at a university or a higher school of learning as designated in regulations in this regard. An "eminent jurist" can also be appointed to the Supreme Court.

The number of Supreme Court Judges is determined by a resolution of the Knesset. Currently, there are 15 Supreme Court Judges.

At the head of the Supreme Court and at the head of the judicial system as a whole is the President of the Supreme Court, and the Deputy President. A judge serves until reaching 70 years of age, or the judge resigns, dies, is appointed to a position which is disqualifying from continued service as a judge, or is removed from office.

Current judges

As of October 2023, the Supreme Court judges are:

| Position | Judge | Nominated by | Appointed by | Start date | Tenure as president | Expected retirement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acting/Deputy President of the Supreme Court | .jpg.webp) |

עוזי פוגלמן

(1954, Israel) |

Yaakov Neeman | Shimon Peres | 14 October 2009 | – | 6 October 2024 | |

| Supreme Court Judge |  |

יצחק עמית

(1958, Israel) |

Yaakov Neeman | Shimon Peres | 14 October 2009 | – | 20 October 2028 | |

| Supreme Court Judge |  |

נעם סולברג

(1962, Israel) |

Yaakov Neeman | Shimon Peres | 21 February 2012 | – | 22 January 2032 | |

| Supreme Court Judge |  |

דפנה ברק-ארז

(1965, United States) |

Yaakov Neeman | Shimon Peres | 31 May 2012 | – | 2 January 2035 | |

| Supreme Court Judge |  |

דוד מינץ

(1959, UK) |

Ayelet Shaked | Reuven Rivlin | 13 June 2017 | N/A | 8 May 2029 | |

| Supreme Court Judge |  |

יוסף אלרון

(1955, Israel) |

Ayelet Shaked | Reuven Rivlin | 30 October 2017 | N/A | 20 September 2025 | |

| Supreme Court Judge |  |

יעל וילנר

(1959, Israel) |

Ayelet Shaked | Reuven Rivlin | 30 October 2017 | N/A | 22 September 2029 | |

| Supreme Court Judge |  |

עופר גרוסקופף

(1969, Israel) |

Ayelet Shaked | Reuven Rivlin | 27 March 2018 | – | 12 October 2039 | |

| Supreme Court Judge |  |

אלכס שטיין | Ayelet Shaked | Reuven Rivlin | 9 August 2018 | N/A | 27 October 2027 | |

| Supreme Court Judge | _(cropped).jpg.webp) |

Gila Canfy-Steinitz | גילה כנפי-שטייניץ

(1958, Israel) |

Gideon Sa'ar | Isaac Herzog | 6 March 2022 | N/A | 2028 |

| Supreme Court Judge |  |

Khaled Kabub | ח'אלד כבוב

(1958, Israel) |

Gideon Sa'ar | Isaac Herzog | 9 May 2022 | N/A | 3 March 2028 |

| Supreme Court Judge |  |

Ruth Ronnen | רות רונן

(1962, Israel) |

Gideon Sa'ar | Isaac Herzog | 9 June 2022 | N/A | 2032 |

| Supreme Court Judge | _(cropped)_(cropped).jpg.webp) |

Yechiel Kasher | יחיאל כשר

(1961, Israel) |

Gideon Sa'ar | Isaac Herzog | 9 June 2022 | N/A | 9 June 2031 |

| Supreme Court Judge | – | seat vacant | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Keren Azulay and Lior Mishaly Shlomai serve as the Court Magistrate Judges (or "Registrars").[5]

Court presidents

Below is a list of presidents of the Supreme Court.

- Moshe Smoira (1948–1954)

- Yitzhak Olshan (1954–1965)

- Shimon Agranat (1965–1976)

- Yoel Zussman (1976–1980)

- Moshe Landau (1980–1982)

- Yitzhak Kahan (1982–1983)

- Meir Shamgar (1983–1995)

- Aharon Barak (1995–2006)

- Dorit Beinisch (2006–2012)

- Asher Grunis (2012–2015)

- Miriam Naor (2015–2017)

- Esther Hayut (2017–2023)

Roles of the Supreme Court

Appellate court

| Part of a series on the |

|

|---|

|

|

As an appellate court, the Supreme Court considers cases on appeal (criminal, civil, and military ) on judgments and other decisions of the District Courts. It also considers appeals on judicial and quasi-judicial decisions of various kinds, such as matters relating to the legality of Knesset elections and disciplinary rulings of the Bar Association.

High Court of Justice

As the High Court of Justice (Hebrew: בית משפט גבוה לצדק, Beit Mishpat Gavo'ah LeTzedek; also known as its acronym Bagatz, בג"ץ), the Supreme Court rules on matters within its original jurisdiction, primarily regarding the legality of decisions of State authorities: Government decisions, those of local authorities and other bodies and persons performing public functions under the law, and direct challenges to the constitutionality of laws enacted by the Knesset. The Israeli Defense Forces are also subject to the HCJ's judicial review.[6]

The court has broad discretionary authority to rule on matters in which it considers it necessary to grant relief in the interests of justice, and which are not within the jurisdiction of another court or tribunal.[7] The High Court of Justice grants relief through orders such as injunction, mandamus and Habeas Corpus, as well as through declaratory judgments.

Further hearing

The Supreme Court can also sit at a “further hearing” on its own judgment. In a matter on which the Supreme Court has ruled, whether as a court of appeals or as the High Court of Justice, with a panel of three or more Judges, it may rule at a further hearing with a panel of a larger number of Judges. A further hearing may be held if the Supreme Court makes a ruling inconsistent with a previous ruling or if the Court deems that the importance, difficulty or novelty of a ruling of the Court justifies such hearing.

Composition

The Supreme Court, both as an appellate court and the High Court of Justice, is normally constituted of a panel of three Judges. A single Supreme Court Judge may rule on interim orders, temporary orders or petitions for an order nisi, and on appeals on interim rulings of District Courts, or on judgments given by a single District Court judge on appeal, and on a judgment or decision of the Magistrates’ Courts.

The Supreme Court sits as a panel of five Judges or more in a rehearing on a matter in which the Supreme Court sat with a panel of three Judges. The Supreme Court may sit as a panel of a larger uneven number of Judges than three in matters that involve fundamental legal questions and constitutional issues of particular importance.

Presiding Judge

In a case on which the President of the Supreme Court sits, the President is the Presiding Judge; in a case on which the Deputy President sits and the President does not sit, the Deputy President is the Presiding Judge; in any other case, the Judge with the greatest length of service is the Presiding Judge. The length of service, for this purpose, is calculated from the date of the appointment of the Judge to the Supreme Court.

Retrial

A special power, unique to the Supreme Court, is the power to order a "retrial" on a criminal matter in which the defendant has been convicted by a final judgment. A ruling to hold a retrial may be made where the Court finds that evidence provided in the case was based upon lies or was forged; where new facts or evidence are discovered that are likely to alter the decision in the case in favor of the accused; where another has meanwhile been convicted of carrying out the same offense and it appears from the circumstances revealed in the trial of that other person that the original party convicted of the offense did not commit it; or, where there is a real concern for miscarriage of justice in the conviction. In practice, a ruling to hold a retrial is very rarely made.

Judicial opinions

The Court announces its judgments through individually signed opinions setting out the result and underlying reasoning. In general, there is a lead opinion for the majority, but there is no "opinion of the Court" as such. Each participating Judge will either note that she or he concurs in the lead opinion (and possibly another opinion as well) or write a separate concurrence. It is not unusual for most or all of the participating Judges to write separately, even when they agree as to the outcome.

The Court's opinions are available in Hebrew on its own website and from Nevo. A relatively small subset has been translated into English. These are available in a searchable online database at Versa. They can also be found on the Court's own site and have been published in hard copy in annual volumes by William S. Hein & Co. as the Israel Law Reports. In addition, the Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in cooperation with the Court, has published three volumes of English translations of selected decisions entitled Judgments of the Israel Supreme Court: Fighting Terrorism within the Law. These are part of the Versa database and also can be found online at the MFA's website.

Intervention

In the 1980s and the 1990s, the Supreme Court established its role as a protector of human rights, intervening to secure freedom of speech and freedom to demonstrate, reduce military censorship, limit the use of certain military methods[8] and promote equality between various sectors of the population.[9] However critics question the role of the court in protecting the human rights of Palestinians in Judea and Samaria and point to double standards in their application.[10]

Public perception

According to a 2017 poll by non-profit organization Israel Democracy Institute, the Supreme Court is the only State institution that the majority of both Jewish (57%) and Arab (54%) Israelis have trust in,[11] marking a slight increase from their 2016 poll.[12]

The Institute's 2017 poll on the statement "[t]he power of judicial review over Knesset legislation should be taken away from the Supreme Court" found that 58% of Israelis disagree, 36% agree, and 6% do not know.[13]

Trust in the court has since dropped dramatically, with a 2022 poll shows trust in the court dropping to just 41% among Jews,[14] and opposition to an "overide clause", allowing the Knesset to nulify supreme court decisions with a 61 vote majority, dropping to just 48%.[15]

Judicial reforms

The 2023 Israeli judicial reform is a proposed series of changes to the judicial system and the balance of powers in Israel put forward by the current Israeli government, and spearheaded by Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Justice Yariv Levin and the Chair of the Knesset's Constitution, Law and Justice Committee, Simcha Rothman. It seeks to curb the judiciary's influence over lawmaking and public policy by limiting the Supreme Court's power to exercise judicial review, granting the government control over judicial appointments and limiting the authority of government legal advisors. If adopted, the reform would grant the Knesset the power to override Supreme Court rulings by a majority of 61 or more votes, diminish the ability of the court to conduct judicial review of legislation and of administrative action, prohibit the court from ruling on the constitutionality of basic laws, and change the makeup of the Judicial Selection Committee so that a majority of its members are appointed by the government. The legislation is currently being considered by the Knesset and the relevant committees.

Architecture

_-_An_aerial_photo_of_the_supreme_court_building.jpg.webp)

The building was donated to Israel by the Jewish philanthropist Dorothy de Rothschild.[16] Outside the President's Chamber has displayed the letter Ms. Rothschild wrote to Prime Minister Shimon Peres expressing her intention to donate a new building for the Supreme Court.[17]

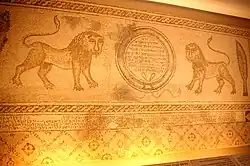

It was designed by Ram Karmi and Ada Karmi-Melamede and opened in 1992.[18] According to the critic Ran Shechori, the building is a "serious attempt to come to grips with the local building tradition". He writes that,

It makes rich and wide-ranging references to the whole lexicon of Eretz-Israel building over the centuries, starting with Herodian structures, through the Hellenistic tomb of Absalom, the Crusaders, Greek Orthodox monasteries, and up to the British Mandate period. This outpouring is organized in a complex, almost baroque structure, built out of contrasts light-shade, narrow-wide, open-closed, stone-plaster, straight-round, and a profusion of existential experiences.[19]

Paul Goldberger of The New York Times calls it "Israel's finest public building," achieving "a remarkable and exhilarating balance between the concerns of daily life and the symbolism of the ages." He notes the complexity of the design with its interrelated geometric patterns:

There is no clear front door and no simple pattern to the organization. The building cannot be described solely as long, or solely as rounded or as being arranged around a series of courtyards, though from certain angles, like the elephant described by the blind man, it could be thought to be any one of these. The structure, in fact, consists of three main sections: a square library wing within which is set a round courtyard containing a copper-clad pyramid, a rectangular administrative wing containing judges' chambers arrayed around a cloistered courtyard and a wing containing five courtrooms, all of which extend like fingers from a great main hall.[20]

The building is a blend of enclosed and open spaces; old and new; lines and circles.[18] Approaching the Supreme Court library, one enters the pyramid area, a large space that serves as a turning point before the entrance to the courtrooms. This serene space acts as the inner "gatehouse" of the Supreme Court building. The Pyramid was inspired by the Tomb of Zechariah and Tomb of Absalom in the Kidron Valley in Jerusalem.[18] Natural light enters round windows at the apex of the pyramid, forming circles of sunlight on the inside walls and on the floor.[21]

References

- Version of emblem of Israel used by the Judicial Authority. court.gov.il

- Reasonableness bill passes 64-0 after compromise falls at last minute

- "The Judiciary: The Court System". Archived from the original on June 15, 2013.

- "The Judiciary: The Court System". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

- Justices and Registrars of the Supreme Court

- Watt, Horatia Muir; Arroyo, Diego P. Fernández (2014). Private International Law and Global Governance. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-104337-6.

- Coercing Virtue: The Worldwide Rule of Judges / Robert Bork (2003) ISBN 0-8447-4162-0 Chapter 4

- Samia Chouchane, « The judicialization of the Israeli military Ethics. A political analysis of the Supreme Court's role in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict », Bulletin de Recherche du Centre de Recherche Français à Jérusalem, 20 | 2009

- Dorit Beinish (December 6, 2002). "Protecting Democracy and Human Rights in Tense Times: the Israeli Supreme Court". Israel21c.org. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- Shamir, Ronen (1990). "Landmark Cases and the Reproduction of Legitimacy: The Case of Israel's High Court of Justice". Law and Society Review. 24 (3): 781–805. doi:10.2307/3053859. JSTOR 3053859.

- "IDI Releases 2017 Israeli Democracy Index". en.idi.org.il. Retrieved September 20, 2018. – Direct link to poll graph on State institutions

- "IDI Releases 2016 Israeli Democracy Index". en.idi.org.il. Retrieved September 20, 2018. – Direct link to poll graph on State institutions

- "IDI Releases 2017 Israeli Democracy Index". en.idi.org.il. Retrieved September 20, 2018. – Direct link to poll graph on the Supreme Court

- ohadr (January 6, 2022). "נמשכת הירידה באמון הציבור בבית המשפט העליון". מקור ראשון (in Hebrew). Retrieved January 6, 2023.

- "N12 - סקר מיוחד של "אולפן שישי": מה חושב הציבור על המינוי של..." N12. November 26, 2022. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

- New York Times Obituary – Dorothy de Rothschild

- The Judicial Authority Tour of Supreme Court – The Presidents Chamber

- "Supreme Court of Israel, Official Website". Elyon1.court.gov.il. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- ""Architecture in Israel 1995–1998", The Israel Review of Arts and Letters – 1995/99-100". Mfa.gov.il. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- "Paul Goldberger, "ARCHITECTURE VIEW; A Public Work That Ennobles As It Serves"". The New York Times. August 13, 1995. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- Tourism.gov.il (March 5, 2011). "Supreme Court building". Tourism.gov.il. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

External links

- Supreme Court of Israel Official website

- Jewish Virtual Library: The Judicial Branch

- Harvard Law School guide to finding selected decisions and opinions translated to English.

- Versa (Cardozo Law School site devoted to the Israeli Supreme Court, including English translations of several hundred opinions)

- Israel 365 News "The Torah and Judicial Reform" January 29,2023