Ivan I of Moscow

Iván I Danilovich Kalitá (Russian: Ива́н I Данилович Калита́; 1 November 1288 – 31 March 1340 or 1341[1]) was Grand Prince of Moscow[2] from 1325 to at least 1340, and Grand Duke of Vladimir from 1332 until at least 1340.[3]

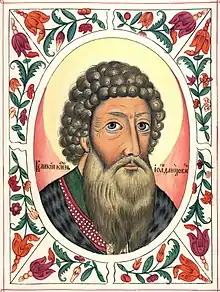

| Ivan I | |

|---|---|

Miniature from the Tsarskiy titulyarnik ("Tsar's Book of Titles", 1672) | |

| Prince of Moscow | |

| Reign | 21 November 1325 – 31 March 1340 or 1341 |

| Predecessor | Yury |

| Successor | Simeon I |

| Born | 1 November 1288 Moscow, Duchy of Moscow |

| Died | 31 March 1340 or 1341 (aged 51–52) Moscow, Duchy of Moscow |

| Burial | |

| Consort | 1.Elena Aleksandra; 2.Ulyana |

| Issue more... | Simeon Ivanovich Ivan Ivanovich |

| House | Daniilovichi |

| Father | Daniel of Moscow |

| Mother | Maria |

| Religion | Russian Orthodox Church |

Biography

Ivan was the son of the Prince of Moscow Daniil Aleksandrovich.

After the death of his elder brother Yury, Ivan inherited the Principality of Moscow. Ivan participated in the struggle to get the title of Grand Duke of Vladimir which could be obtained with the approval of a khan of the Golden Horde. The main rivals of the princes of Moscow in this struggle were the princes of Tver – Mikhail, Dmitry the Terrible Eyes, and Alexander II, all of whom obtained the title of Grand Duke of Vladimir and were deprived of it. All of them were murdered in the Golden Horde. In 1328 Ivan Kalita received the approval of khan Muhammad Ozbeg to become the Grand Duke of Vladimir with the right to collect taxes from all Rus' lands.

According to the Imperial Russian historian Vasily Klyuchevsky, the rise of Moscow under Ivan I Kalita was determined by three factors. The first one was that the Moscow principality was situated in the middle of other Rus' principalities; thus, it was protected from any invasions from the East and from the West. Compared to its neighbors, Ryazan principality and Tver principality, Moscow was less often devastated. The relative safety of the Moscow region resulted in the second factor of the rise of Moscow – an influx of working and tax-paying people who were tired of constant raids and who actively relocated to Moscow from other Rus' regions. The third factor was a trade route from Novgorod to the Volga river.

According to Baumer,[4] Öz Beg Khan took a fateful decision when he abandoned the former policy of divide and rule by making the new grand prince responsible for collecting and passing on all the tribute and taxes from all Rus' cities. Ivan delivered these exactions punctually, so further strengthening his position of privilege. In this way he laid the foundations for Moscow's future as a regional great power.

Ivan Kalita intentionally pursued the policy of relocation of people to his principality by an invitation of people from other places and by purchase of Rus' people captured by Mongols during their raids. He managed to eliminate all the thieves in his lands, thus ensuring the safety of traveling merchants. Internal peace and order together with the absence of Mongolian raids to the Moscow principality was mentioned in Rus' chronicles as “great peace, silence, and relief of Rus' land.

Ivan made Moscow very wealthy by maintaining his loyalty to the Horde (hence, the nickname Kalita, or the Moneybag[5]). He used this wealth to give loans to neighbouring Rus' principalities. These cities gradually fell deeper and deeper into debt, a condition that would eventually allow Ivan's successors to annex them. He bought lands around Moscow, and very often the poor owners sold their lands willingly. Some of them kept the right to rule in their lands on behalf of Ivan Kalita. In one way or another a number of cities and villages joined the Moscow principality – Uglich in 1323, the principality of Belozero in 1328–1338, and the principality of Galich in 1340. Ivan's greatest success, however, was convincing the Khan in Sarai that his son, Simeon The Proud, should succeed him as the Grand Duke of Vladimir and from then on this position almost always belonged to the ruling house of Moscow. The Head of the Russian Church – Metropolitan Peter, whose authority was extremely high, moved from Vladimir to Moscow to Prince Ivan Kalita.

Following a Lithuanian raid on the town of Torzhok in 1335 (as part of the Muscovite–Lithuanian Wars), Ivan retaliated by burning the towns of Osechen and Riasna.[6]

Ivan died in Moscow, 31 March 1340 or 1341.[1] He was buried 1 April in the Church of the Archangel Michael.[1] Ivan had built the church and was also the first person to be buried there.[7]

Family

Ivan Kalita was married twice. His first wife was called Elena, and nothing is known exactly about her origin. There is a hypothesis that she was the daughter of the prince of Smolensk, Alexander Glebovich.[8]

From marriage were born:

- Simeon Ivanovich (7 November 1316 – 27 April 1353), future Grand Duke of Moscow;

- Daniel Ivanovich (11 December 1319/20–1328);

- Fefinia Ivanovna (died young);

- Maria Ivanovna (died 2 June 1365), married to Prince Konstantin of Rostov in 1328.;

- Ivan Ivanovich (30 March 1326 – 13 November 1359), future Grand Duke of Moscow;

- Andrei Ivanovich (4 August 1327 – 6 June 1353), Prince of Novgorod;

- Evdokia Ivanovna (1314 – 1342), married to Vasili Mikhailovich, Prince of Iaroslavl. They were the ancestors of the Princes of Shakhovskoy, possibly the most senior remaining branch of the Rurikids;

- Feodosia Ivanovna (died 1389), married to Fyodor Romanovich, Prince of Belozersky .

Princess Elena died on 1 March, 1331. A year later, Ivan married again, although only the given name of his second wife is known - Ulyana . There is a hypothesis that she was a daughter of Fyodor Davydovich Galitsky, who received half of her father's principality as a dowry. According to A. V. Eksemplyarsky, this second marriage produced one daughter; while V.A. Kuchkin suggested there were two daughters: Maria and Theodosia, who appear in the prince's will as "young children". One of them was alive in 1359; nothing more is known about the other. Ulyana survived her husband and died between 1366 and 1372.

Legacy

Under Ivan Kalita, Moscow was actively growing, and his residence on the Borovitsky hill became the main part of the city. Erection of either wooden or white-stone constructions was started in the Kremlin. A number of churches were built: in 1326–1327 the Assumption Cathedral, in 1329 the Church of Ivan of the Ladder (John Climacus), in 1330 the Cathedral of the Saviour on the Bor (Forest), and in 1333 the Cathedral of Archangel Michael, where Ivan Kalita and his descendants were buried. Between 1339 and 1340, Ivan Kalita erected a new, bigger oaken fortress on the Borovitsky hill.

In Ivan’s will “the golden cap” was mentioned for the first time; this cap is identified with the well-known Monomakh’s crown, the main crown of Russian sovereigns.

In an oration written in the 1470s (about 135 years after his death) praising the life of Ivan I's grandson Dmitry Donskoy (r. 1359–1389), Ivan Kalita was retroactively referred to as the ‘gatherer of the Rus' land'.[9] This was part of a wider effort by Muscovite writers in the late 15th century to claim that the authority of the Grand Princes of Kievan Rus' had been transferred from Kyiv to Vladimir on the Klyazma, and then to Moscow, thus arguing (against other princely claimants from Kyiv, Lithuania, and elsewhere) that the Muscovite rulers were the only true legitimate heirs to the Rurikid dynasty, and the Rus' land.[10]

See also

References

- Basil Dmytryshyn, Medieval Russia:A source book, 850-1700, (Academic International Press, 2000), 194.

- Frankopan, P. (27 August 2015). The Silk Roads: A New History of the World. Vintage Books. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-101-91237-9.

- Basil Dmytryshyn, Medieval Russia:A source book, 850-1700, 190.

- Christoph Baumer, History of Central Asia, 2016, v3, p268

- Basil Dmytryshyn, Medieval Russia:A source book, 850-1700, 195.

- S. C. Rowell, Lithuania Ascending:A Pagan Empire within East Central Europe, 1295-1345, (Cambridge University Press, 1994), 250.

- Cherniavsky, M. (1975). Ivan the terrible and the iconography of the kremlin cathedral of archangel michael. Russian History, 2(1), 3-28. doi:10.1163/187633175X00018

- Averyanov K. Principality of Moscow under Ivan Kalita (Accession of Koloman. Acquisition of Mozhaisk). - M., p. 36, 1994.

- Plokhy 2006, p. 136.

- Plokhy 2006, p. 136–138.

Sources

- V. O. Kluchevsky. The course of Russian history. Lecture #21

- Janet Martin, Medieval Russia 980–1584

- Plokhy, Serhii (2006). The Origins of the Slavic Nations: Premodern Identities in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 378. ISBN 978-0-521-86403-9.

External links

- Bain, Robert Nisbet (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). pp. 87–91.

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)