Ivan Goremykin

Ivan Logginovich Goremykin (Russian: Ива́н Лóггинович Горемы́кин; 8 November 1839 – 24 December 1917) was a Russian politician who served as the prime minister of the Russian Empire in 1906 and again from 1914 to 1916, during World War I. He was the last person to have the civil rank of Active Privy Councillor, 1st class. During his time in government, Goremykin pursued conservative policies.

Ivan Goremykin | |

|---|---|

| Иван Горемыкин | |

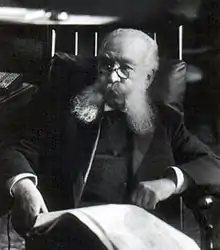

Ivan Goremykin, c. 1906 | |

| 2nd Prime Minister of Russia | |

| In office 5 May 1906 – 21 July 1906 | |

| Monarch | Nicholas II |

| Preceded by | Sergei Witte |

| Succeeded by | Pyotr Stolypin |

| In office 12 February 1914 – 2 February 1916 | |

| Monarch | Nicholas II |

| Preceded by | Vladimir Kokovtsov |

| Succeeded by | Boris Stürmer |

| Minister of Internal Affairs of Russia | |

| In office 15 October 1895 – 20 October 1899 | |

| Preceded by | Ivan Durnovo |

| Succeeded by | Dmitry Sergeyevich Sipyagin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ivan Logginovich Goremykin 8 November 1839 Novgorod, Novgorod Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 24 December 1917 (aged 78) Sochi |

| Cause of death | Homicide |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Alma mater | Imperial School of Jurisprudence |

| Occupation | Politician |

Biography

Goremykin was born on 8 November 1839 into a noble family. In 1860 he completed studies at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence and became a lawyer in Saint Petersburg. In the Senate, Goremykin became responsible for agriculture in Congress Poland. In 1866 he was appointed as vice governor in Płock and in 1869 in Kielce. In 1891 he was appointed as deputy minister of justice, considered an expert on the "peasant question".

Within a year he moved to the Ministry of the Interior, becoming Minister from 1895 to 1899. A self-described "man of the old school" who viewed the Tsar as the "anointed one, the rightful sovereign", Goremykin was a loyal supporter of Nicholas II as autocrat and accordingly pursued conservative policy. He was apparently well liked by the Empress Alexandra (in 1894 he was appointed as senator; in 1896 as Actual Privy Councillor and became a member of the Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society). In 1897 Vladimir Chertkov, a leading member of the Tolstoyan movement, was banned by Goremykin or his ministry.[1]

While heading the Interior Ministry he submitted a proposal to the tsar advocating administrative reform and the expansion of the zemstvo program and representation within the existing zemstvos. Faced with opposition to the program, he left the position in 1899. In April 1906, Sergei Witte, a reformist, was succeeded by Goremykin. In the Russian Constitution of 1906 the tsar, regretting his 'moment of weakness' when signing the October Manifesto, retained the title of autocrat and maintained his unique dominating position in relation to the Russian Church.[2] Goremykin's unwavering opposition to the political reform demanded by the First Duma left him unable to work with that body and he resigned in July 1906 after a conflict about ministerial responsibility and rejecting radical agrarian reforms proposed by Duma. He was replaced by his Minister of Interior, the younger and more forceful Pyotr Stolypin.

Called back to service by the tsar, he again served as Chairman of the Council of Ministers (Prime Minister) from April 1914 to February 1916. Vladimir Kokovtsov was replaced by the decrepit and absent-minded Goremykin, and Pyotr Bark as Minister of Finance. Seventy-five years of age, a conservative, and a life-long bureaucrat, he was, in his own words, 'pulled like a winter coat out of mothballs', to lead the government. The hostility expressed toward him by members of both the State Duma and the Council of Ministers greatly impaired the effectiveness of his government. When Nicholas II decided to take direct command of the army, Goremykin and Alexander Krivoshein begged the tsar not to lead the army and leave the capital. All the ministers realized that the change would put the empress and Rasputin in charge and threatened to resign.[3][4] Goremykin urged the Council to endorse the decision. When they refused, Goremykin told the tsar that he was not fitted and asked to be replaced with "a man of more modern views". He held a hostile attitude towards the Imperial Duma and the Progressive Bloc. In January 1916 Rasputin was opposed to the plan to send the old Goremykin away,[5] and he told Goremykin it was not right not to convene the Duma, as all were trying to cooperate; one must show them a little confidence.[6] His wish for retirement was granted at the beginning of February 1916, when he was replaced by Boris Stürmer. Stürmer was not opposed to the convening of the Duma, as Goremykin had been, and he would launch more liberal and conciliatory policies.

After the February Revolution in 1917, he was arrested and interrogated before the "Extraordinary Commission of Inquiry for the Investigation of Illegal Acts by Ministers and Other Responsible Persons of the Czarist Regime". In May Alexander Kerensky agreed to his release, on condition that he retired to his dacha in Sochi. On 24 December 1917 he was murdered in a robbery raid, together with his wife, his daughter, and father-in-law.

Legacy

Goremykin's conservatism and inability to function in a semi-parliamentary system made him largely unsuitable for the position of head of government during the last years of Imperial Russia. Goremykin was despised by parliamentarians and revolutionaries and personally desired only to retire, and the ineffectiveness of his last government contributed to the instability and ultimate downfall of the Romanov dynasty.

Quotations

- "The Emperor can't see that the candles have already been lit around my coffin and that the only thing required to complete the ceremony is myself" (commenting on his advanced age and unsuitability for office).

- "To me, His Majesty is the anointed one, the rightful sovereign. He personifies the whole of Russia. He is forty-seven and it is not just since yesterday that he has been reigning and deciding the fate of the Russian people. When the decision of such a man is made and his course of action is determined, his faithful subjects must accept it whatever may be the consequences. And then let God's will be fulfilled. These views I have held all my life and with them I shall die."

References

- Popoff, Alexandra (15 November 2014). Tolstoy's False Disciple: The Untold Story of Leo Tolstoy and Vladimir Chertkov. Pegasus Books. ISBN 9781605987279 – via Google Books.

- Riasanovsky, N.V. (1977) A History of Russia, p. 453.

- Fuhrmann, pp. 148–149

- Moe, pp. 331–332.

- Frank Alfred Golder (1927) Documents of Russian History 1914–1917. Read Books. ISBN 1443730297.

- The Complete Wartime Correspondence of Tsar Nicholas II and the Empress Alexandra. April 1914-March 1917, p. 317. By Joseph T. Fuhrmann, ed.

Bibliography

- Fuhrmann, Joseph T. (2013). Rasputin: The Untold Story (illustrated ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-1-118-17276-6.

- Massie, Robert K. Nicholas and Alexandra. New York: Ballantine, 1967, 2000. ISBN 978-0-345-43831-7 (pp. 216, 220, 319, 347, 349–350, 526).

- Moe, Ronald C. (2011). Prelude to the Revolution: The Murder of Rasputin. Aventine Press. ISBN 1593307128.

- Ferdinand Ossendowski (1921). Witte, Stolypin, and Goremykin. Translated by F. B. Czarnomski (New York: E.P.Dutton, 1925). It was republished in Sarmatian Review, vol. XXVIII, no. 1 (January 2008), pp. 1351–1355.

External links

Media related to Ivan Goremykin at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ivan Goremykin at Wikimedia Commons