Ivrea Morainic Amphitheatre

The Ivrea Morainic Amphitheatre (sometimes abbreviated as AMI) is a moraine relief of glacial origin located in the Canavese region.[note 1] Administratively, it encompasses the metropolitan city of Turin and, more marginally, the province of Biella and the province of Vercelli. It dates back to the Quaternary period and was created by the transport of sediment to the Po Valley that took place during the glaciations by the great glacier that ran through the Dora Baltea valley. With an area of more than 500 km2, it is one of the best-preserved geomorphological units of this type in the world.[1] As an extension, it is surpassed in Italy only by the similar formation surrounding Lake Garda.[2] The name amphitheater, usually given to these geomorphological structures, refers to their characteristic elliptical shape that is noticeable when it is shown as a plan on a map.

| Ivrea Morainic Amphitheatre | |

|---|---|

AMI satellite photo; in dark green the hills at the outlet of the Aosta Valley on the Po Valley | |

| Highest point | |

| Coordinates | 45.465°N 7.875°E |

| Geography | |

Orography

Throughout the area concerned, the various glacial pulsations that have produced impressive moraine accumulations over time are clearly evident. Of particular note among these is the left lateral moraine of the ancient glacier, known as the Serra di Ivrea: this is the largest formation of its kind existing in Europe.[3] The Serra originates on the southern slopes of Mombarone (2371 m a.s.l.) and heads in an almost straight path southeastward for almost 20 km, then fraying into the heights surrounding Lake Viverone. It consists of a series of sub-parallel ridges, the highest of which reaches a maximum elevation difference of 600 meters from the AMI inner plain in the Andrate area. This elevation difference gradually decreases eastward until it reaches about 250 meters near Zimone.[4]

Its right-hand counterpart, less regular in shape, is represented by the elevations located between Bairo and the outlet of the Chiusella stream on the plain. Here, as well, the highest altitudes are reached in the weld zone with the alpine chain (about 800 m a.s.l. near Brosso); between Strambinello and Baldissero Canavese the continuity of the hill chain is then interrupted by the gorge by which the Chiusella veers eastward heading toward the confluence with the Dora Baltea.[5]

The frontal moraine, on the other hand, consists of a succession of hills that extend between Agliè and Viverone and are interrupted between Mazzè and Villareggia by the gap opened by the Dora Baltea. The high point of this moraine sector is Bric Vignadoma (520 m a.s.l.), near Vialfrè.[5]

Within the amphitheater lies the vast flat area, whose elevation is generally between 210 and 270 m above sea level, in which numerous population centers, including the city of Ivrea, are located.[5] The continuity of this plain is interrupted here and there by isolated reliefs and a few minor hilly cordons; one of these defines within it the Small Morainic Amphitheater, centered on the towns of Strambino and Scarmagno.[1] The catchment area of Lake Viverone is also defined not only by the outer moraine circle of the AMI, but also by smaller internal deposits; the municipalities in this area have grouped into the hill community around the lake.[6]

According to the SOIUSA orographic classification, the elevations located on the hydrographic right of the Dora belong to the Graian Alps and, more specifically, to the Rosa dei Banchi alpine group, while the moraines on the hydrographic left are part of the Biellese Alps and therefore also of the Pennine Alps.[7]

Hydrography

The AMI is traversed in a north-south direction by the Dora Baltea, which also collects water from the Chiusella and other minor streams. Some of the water carried by the Dora is collected by the Naviglio di Ivrea and, after providing water for Vercelli's rice-growing industry, is diverted to the Sesia basin.[8] The outer slopes of the hills that make up the AMI are tributaries of the Orco (to the west) and Elvo (and east) basins.

Nestled among the various moraine cordons that make up the amphitheater are numerous lakes whose formation is closely related to the geological history of the AMI. While Lake Viverone is quite large (in terms of surface area it is the third largest body of water in Piedmont) the others are small to medium in size. Just north of Ivrea are located the 5 lakes, the largest of which is Sirio; the right side moraine, on the other hand, hosts Alice Lake and Meugliano Lake, while between the hills that make up the frontal moraine are Candia Lake and the smaller ones of Maglione and Moncrivello.

The largest of these bodies of water belong to the category of moraine-dammed lakes, that is, they were trapped between moraine cords deposited during the various glacial pulsations that affected the area. In other cases, however, the geological origin is referred more directly to glacier action: indeed, Lake Alice and the 5 lakes of Ivrea are considered by geologists to be glacial erosion lakes.[9]

| Lake | Sup. body of water (km2)[9] | Sup. basin (km2)[9] | Altitude (m a.s.l.)[9] | Origin[9] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lago di Viverone | 5,72 | 25,7 | 229 | Moraine-dammed lake |

| Lago di Candia | 1,35 | 7,5 | 227 | Moraine-dammed lake |

| Lake Sirio | 0,29 | 1,4 | 266 | Glacial lake |

| Lago di Bertignano | 0,09 | 0,6 | 377 | Moraine-dammed lake |

| Lago di Campagna | 0,1 | 4,1 | 238 | Glacial lake |

| Lago Nero | 0,1 | 1,3 | 299 | Glacial lake |

| Lago di Alice | 0,096 | 1,05 | 575 | Glacial lake |

| Lago di Moncrivello | 0,03 | 0,3 | 263 | Moraine-dammed lake |

| Lago San Michele | 0,07 | 0,7 | 239 | Glacial lake |

| Lago Pistono | 0,12 | 2,8 | 280 | Glacial lake |

| Lago di Meugliano | 0,029 | 0,18 | 717 | Moraine-dammed lake |

| Lago di Maglione | 0,05 | 2,7 | 251 | Moraine-dammed lake |

Geology

Even before the birth of modern geology, some legends widespread in the Canavese area told of the existence in the AMI area of a vast lake (the existence of which is denied by geologists)[note 2] which Ypa, the mythical queen-priestess who led the Salassi people, is said to have reclaimed by having a tunnel dug near Mazzè so as to discharge its waters outside the circle of hills that acted as an embankment to the south.[10] Traces of this legend may also be found in the chronicle De bello canepiciano, compiled by Pietro Azario in the 14th century, in which the ancient presence of a large lake in the area is reported as certain news.[11] Beginning in the second half of the 19th century, the origin of the AMI was studied by various Piedmontese geologists; the first classical studies can be credited to Luigi Bruno (1877), Carlo Marco (1892, 1893) and the geographer Giovanni De Agostini (1894, 1895). These studies were later deepened culminating in the synthesis works of the 1970s by geologist Francesco Carraro.[12]

The substrate

The rocky substrate on which the Ivrea Morainic Amphitheatre stands today belongs to three distinct geological units, separated from each other by the Insubric Line. This major tectonic discontinuity divides in the Biella and Canavese area into two faults with an almost parallel trend:[13] the Inner Canavese Line, more southerly, and the Outer Canavese Line, more northerly. In the AMI zone north of the Outer Canavese Line is the Sesia-Lanzo Zone, composed mainly of mica schists and, in general, rocks that underwent metamorphic processes at depth; it includes Mombarone on the hydrographic left and Mount Gregorio on the opposite side of the Dora River.[14] Between the two Canavese lines is the Canavese Zone, an area geologically characterized by rather heterogeneous lithological types and emerging near Montalto Dora and the 5 lakes. South of the Inner Canavese Line, on the other hand, the bedrock belongs to the Ivrea zone. Among the various types of rocks that make up this geological unit in the AMI area are particularly rare basic granulites, which, according to geological studies, originated from the deepest portions of the continental crust near its boundary with the Earth's mantle. Part of the city of Ivrea was built on this rocky substrate, which surfaces prominently near the sanctuary of Monte Stella.[14]

Glacial phases

According to geologists, in the final phase of the Pliocene, the geological period that preceded the formation of the morainic amphitheater, in the Canavese area the sea that occupied the Po River basin at that time and reached into the interior of the Aosta and Orco valleys was gradually filled in by sediments originating from the erosion of the Alpine range.[14]

The AMI, on the other hand, formed during the Pleistocene when, due to decreasing average temperatures and increased precipitation over the Alpine arc, a considerable mass of ice began to accumulate and was carried downstream by large glaciers. In particular, the valley floor of what is now Aosta Valley was on several occasions totally occupied by the Balteo Glacier, which, with a path similar to that of today's Dora Baltea, exited onto the Canavese plain and then widened in a fan-like pattern, reaching as far as to lap, in the most intense glaciation phases, the present-day settlements of Caluso and Agliè.

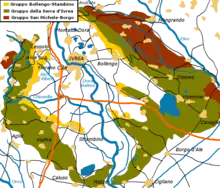

The glacial phases of the Pleistocene were traditionally divided by geological literature into Mindel, Riss and Würm. In the past, the designation of the three main moraine circles constituting the AMI was borrowed directly from these sub-periods, the temporal subdivision of which was determined mainly on the basis of studies of the effects of glaciation north of the Alps. Later this classification was no longer considered sufficiently accurate to describe the geological evolution of the basins located south of the Alpine chain,[4] so that the current subdivision of the moraine circles became the one shown in the following table (reworked from the Geological Map of the Serra Morainic Amphitheater):[14]

| Period | Early period (millions of years ago) | Moraine circle | Old attribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Late Pleistocene | 0,13 | Bollengo-Strambino Group | Würm |

| Middle Pleistocene | 0,73 | Serra d'Ivrea Group | Riss |

| Early Pleistocene | 1,65 | San Michele - Borgo Group | Mindel |

The deposits left by the oldest of the three main glacial pulsations (San Michele - Borgo group) are the outermost and are best identified on the left side of the AMI, in the Biella area of the Serra. The frontal moraine and much of the right moraine have in fact been covered by the debris left by the later phase, which began about 700,000 years ago. During this period the best preserved of the three moraine circles, the Serra d'Ivrea group, was deposited. In addition to the main body of the Serra this includes a large part of the frontal moraine observable today (the area roughly between Moncrivello and Torre Canavese) and part of the reliefs located at the outlet of the Valchiusella. The hilly reliefs due to this glacial phase are the ones that reach the greatest heights partly because they were to some extent curbed by the presence of the moraines left by the previous pulsation, which resulted in a higher elevation than would have occurred in the case of undisturbed deposition on a flat area. The third group of deposits, referred to as the Bollengo-Strambino (or also Bollengo-Albiano), is the most recent and is located within the previous two; it includes some moraine cordons of lesser elevation development as well as the Serretta, a low hill that breaks away from the main body of the Serra near Bollengo.[14]

The other glacial episodes that have marked Pleistocene history left no traces in the area because their deposits were later covered and/or displaced by the sedimentary masses related to the three main morainic circles.[4]

The creation of the large morainic apparatuses at the outlet of the Aosta Valley not only had an impact on the area now included in the AMI but also substantially modified the hydrography of the neighboring territories. Paleogeographical research (in particular by geologists Francesco Carraro[15] and Franco Gianotti[16]) shows, for example, that in ancient times the Cervo stream, after leaving the alpine valley of the same name, headed decisively southward and flowed into the Dora Baltea roughly where Verrone stands today. In this reconstruction, the Viona, Elvo and Oropa also went directly into the Dora, whose ancient course was shifted markedly further northeast than it is today. However, the deposition of the enormous morainic apparatus of the Serra and of sedimentary beds east of it changed this configuration and progressively diverted the course of the Cervo eastward, eventually leading it to flow into the Sesia. Sediments transported by the Balteo Glacier also barred the way toward the Dora to the present right tributaries of the Cervo itself, thus conveying their waters toward the Sesia basin as well.[17]

As for the plain inside the amphitheater, on the other hand, it is interesting to note how it is lowered in relation to the surrounding flat areas.[14] For example, on the hydrographic left of the Dora at Moncrivello, whose chief town straddles the moraine circle, the flat areas located inside the amphitheater are at an elevation of about 215 m a.s.l. while those to the east of the town, outside the AMI, have an average elevation around 260 m.[5] This phenomenon is due to the erosive action of the Balteo Glacier, the flow of which, during periods of maximum expansion, lowered the ground level, transferring part of the sediments that made it up into the moraine reliefs being formed.[14]

The interglacial phases

The periods of time between two successive glacial pulsations are called interglacial periods and are characterized, in mountainous and foothill areas, by the retreat of the glacier front within the valleys of origin. In the specific case of the AMI, the most recent geological studies have found, through sediment analysis, that each phase of retreat of the Balteo glacier corresponded to a more or less generalized lacustrine phase. The waters derived from the melting of the glacier and those carried downstream by the Dora River and its tributaries were in fact trapped within the depressions due to plucking and between the abandoned moraine ridges of the retreat of the glacier itself.[12]

One of the consequences of the retreat of the Balteo Glacier was the capture by the Dora Baltea of the upland portion of the Chiusella stream basin. About 150,000 years ago the Chiusella, in the section downstream of the present Gurzia dam, was in fact supposed to flow in a southwesterly direction and then flow into the Orco on the hydrographic left. After the last glaciation, however, the greater gradient and lower resistance to erosion of the rocks on the eastern side of the stream caused an increase in the erosive force of the small streams that, flowing down toward the southeast, went to flow into the Dora Baltea. One of them, moving upward the head of its own small basin, dug the deep gorge still observable today downstream from Lake Gurzia and ended up catching the Chiusella. The latter was thus channeled into the marked elbow bend downstream of which, heading eastward, it goes today to flow into the Dora River.[18]

In the present interglacial period, which began approximately 10,000 years ago, one or more extensive intramoraine lacustrine areas were presumably formed within the AMI, the presence of which is evidenced by finer-grained, well-stratified graded sediments as opposed to heterogeneous, unstratified sediments typical of the moraines that make up the area's reliefs. The emptying of the lacustrine area occurred as a result of the progressive deepening of the incision carved by the Dora Baltea, its distributary, between Mazzè and Villareggia. Trapped between the moraine ridges, however, several smaller bodies of water remained for a long time, some of which still exist today. Among these the largest are Lake Viverone and Lake Candia. Other lake basins of various sizes were gradually filled in by the only partially decomposed remnants of riparian vegetation and formed the numerous peat bogs still visible in the area.

With the progressive silting up of the lacustrine areas left by the retreat of the glacier, the Dora Baltea began to erode the sedimentary cover that constitutes the plains inside the AMI. Its course, which formerly included numerous branches, gradually assumed a single-channel morphology and tended to meander as a result of this deepening. The westernmost branches, which rambled into the Fiorano and Loranzè area, were thus abandoned and the river, passing through the bottleneck between Ivrea and Cascinette, created a well-marked gorge. This state of affairs during exceptional flood events, however, results in the reactivation of the western paleochannel because of the dam effect created when the present Dora riverbed cannot dispose of the flood wave coming from the Aosta Valley. The phenomenon has occurred several times in historical times and in particular, in the 21st century, during the floods of the years 2000, 2002, and 2008,[19] causing considerable damage in the areas traversed by the paleochannel.[note 3]

Paleobotany

With the final phase of the last glaciation, the areas that were being cleared of ice, albeit discontinuously and gradually, were occupied by vegetation that was initially herbaceous and shrubby and then forested. At least a qualitative idea of the evolution of flora in the AMI area can be derived from the study of pollen diagrams obtained from sediments in the Viverone and Alice lake areas dated by radiometric methods.[note 4]

The retreat of the Balteo glacier within the present-day Aosta Valley is generally located around 20,000 years before the present;[20] at this early stage paleobotanical data indicate that the outer bands of the moraine amphitheater were occupied by thickets in which green alder and willows predominated while a continuous forest cover of larch trees had developed around Lake Viverone.

With the further rise in temperatures during the Bølling-Allerød interstadial, there was an abrupt increase in the upper limit of forest vegetation to around 14,000 years ago around 1800 m asl. During this phase, larch was joined by scotch pine, birch, and junipers as the dominant species, and towards the end of the period, there was also a significant expansion of thermophilic broadleaf trees.

With the return of cold temperatures that occurred in the Younger Dryas, the tree line lowered in the area concerned by about 200 to 300 meters in elevation, and trees in large areas gave way to grassland. After about 1,100 years, the cold period ended, and with the mild temperatures characteristic of the Holocene, the forest cover was able to rapidly recover the lost ground.[21]

Human presence and its impact on the territory

The particular geographical conformation of the AMI has greatly conditioned land use and human settlement in the area over time. Today's satellite photographs of the area show, for example, how to this day the moraine hills still differ in the presence of extensive forests from the inland plain and surrounding territories, which are instead characterized by a denser human population and the prevalence of intensive farming.

Prehistory

Even assuming that human settlements had existed within the AMI before the phase of maximum glacial expansion these would not be documentable because the action of the Balteo glacier would have erased all traces of them. There are, however, numerous human testimonies in the area dating back to the Neolithic period and, particularly, to the final phase of the last glacial pulsation of the Early Pleistocene (starting about ten to twelve thousand years ago).[22][23][24] The human population was consolidated during the Bronze Age; among the finds dating back to this period particularly well preserved are those referable to settlements near lake basins that still exist or that over time have been transformed into peat bogs. Of considerable importance, for example, is the research carried out on the pile-dwelling villages of Viverone[25] and Bertignano, where a number of pirogues were also found.[26]

The presence of human settlements around the lakes is evidently not coincidental but testifies to how the inhabitants of this part of the Canavese appreciated the additional food resources provided by fishing and the greater security offered by pile-dwelling settlements compared to those on dry land. Evidence of Bronze and Iron Age human settlements can also be found, however, in areas far from the lakes, such as the megalithic complex of Cavaglià, located in the southeastern area of the AMI.[27] Favorable climatic conditions and the use of metal tools led to some population growth and reinforced an agricultural practice integrated with animal husbandry.[28]

Roman period

In pre-Roman times the Canavese was inhabited by the Salassi, a people of Celtic origin. The first clash with Rome took place in 143 BC, when the Salassi resisted the troops of Consul Appius Claudius Pulcher. There were no noteworthy battles over the next forty years, but certainly Rome's economic penetration continued, which allowed the Senate to found the Roman colony of Eporedia (today's Ivrea[29]) in 100 BC on a pre-existing fortified village of the Salassians. The resistance of the populations in the plain and in the nearby Aosta Valley was resolved in 25 B.C. by Emperor Augustus, who, as narrated by historian Strabo, obtained the surrender of the Salassi and was able to found the municipium of Aosta.[30] As early as 100 B.C. a remarkable transformation in land use began in the AMI: in parallel with the military occupation the settlement of citizens of Roman or Latin origin began, to whom were assigned carefully measured and surveyed plots of land of which the settlers themselves began agricultural exploitation.[31] This land organization of the lowland area took place according to the classic scheme of centuriation, that is, the division of fields with a network of orthogonal lanes and canals; traces of this ancient subdivision can still be found in the Canavese countryside, according to archaeological studies.[32] The AMI area also had considerable commercial importance in the imperial period, being located along Gaul, which, via Augusta Praetoria (Aosta) and the passes of the Little and Great St. Bernard, connected the Po Valley with Gaul.

Middle Ages and Renaissance

The period of crisis following the fall of the Roman Empire and the early Middle Ages were also politically and economically troubled in the Canavese. The area changed hands several times until the final passage under the Savoy family in 1356.[33] As in ancient times, this part of the Canavese in the Middle Ages was traversed by an important communication route: the Via Francigena, which gave pilgrims from central and northern Europe a way to reach the city of Rome. Its Canavesean section, after leaving the Aosta Valley, reached Ivrea and continued southeast, presumably skirting the Serra.[28] Somewhat linked to the presence of the Via Francigena is the flowering of Romanesque architecture, which alongside religious buildings of considerable importance dotted the moraine hills with minor churches and chapels, often located in isolated places. The tops of the hills that make up the AMI were in many cases used for the construction of castles and villages, which benefited in this way from more easily defensible and healthier positions because they were far from the flat areas that tended to be marshy. Viticulture, already practiced before the arrival of the Romans, was consolidated and expanded on the hillsides in the Middle Ages,[34] also favored by a period of particularly mild climate. Viticulture was accompanied by the cultivation of olives, which according to some scholars was even more widespread and was regulated by numerous edicts and local regulations.[35] In the final phase of the medieval period, thanks in part to the relative political stability provided by the Savoy state, the area experienced a fair amount of economic growth; among the various works built in this period is the Naviglio di Ivrea, the construction of which as a navigable canal was initiated by Amadeus VIII based on a design by Leonardo da Vinci with the aim of connecting the city of Ivrea to Vercelli and irrigating the Vercelli countryside.[36]

Modern and contemporary age

The cooling of the climate that occurred between the early 14th century and the mid-19th century caused the disappearance of olive growing in the AMI area;[35] viticulture, on the other hand, continued to be assiduously practiced, also aided by the generalized increase in population until the first half of the 20th century. Various land development activities of the amphitheater wetlands and peat extraction date back to the period between the 19th and early 20th centuries, which then ceased due to the low productivity and limited economic interest of the product obtained. [14][37] With industrialization and the consequent abandonment of agricultural activity in the less fertile areas, noticeable especially after World War II, the less favorable slopes of the moraine hills were left to a natural process of reforestation while in the sunnier areas vine cultivation was preserved, often raised in traditional form on terraces housing tall pergolas (in Piedmontese topie[38]) supported by circular stone columns.[39] Also in the post-World War II period, the AMI was affected by widespread building growth, especially in the area of the inland plain,[40] and the construction of various infrastructures including the Turin-Aosta highway and the A4/A5 - Ivrea-Santhià branch, or the so-called Bretella. Some of these infrastructures, as well as the countryside and towns in the area, were heavily damaged by the flood that hit the AMI area in October 2000 causing the Dora Baltea and several other Piedmont and Valle d'Aosta waterways to overflow.[41]

Nature conservation

Given the environmental importance of the moraine hills and the wetlands they enclose an important portion of the AMI is in various ways protected from a naturalistic point of view.

In particular, the Piedmont Region established the Lake Candia Natural Park of Provincial Interest in 1995.[42]

Also in the Province of Turin and in the AMI area are the following Sites of Community Importance: Pelati Mountains and Torre Cives (cod.IT1110013), Lake Viverone (cod.IT1110020), Ivrea Lakes (cod.IT1110021), Meugliano and Alice Lakes (cod. IT1110034), Scarmagno - Torre Canavese (right moraine of Ivrea) (cod.IT1110047), Mulino Vecchio (cod.IT1110050), Serra di Ivrea (cod.IT1110057, partially in the province of Biella), Maglione and Moncrivello lakes (cod. IT1110061), Settimo Rottaro underground pond (cod.IT1110062), Bellavista woods and marshes (cod.IT1110063), Romano Canavese marshes (cod.IT1110064), Isolotto del Ritano (Dora Baltea) (cod. IT1120013); in addition, in the Province of Biella, there is the SCI Lago di Bertignano (Viverone) and pond near the road to Roppolo (cod.IT1130004).[43][44] Several of these sites have also been designated as SACs.[45]

The morainic amphitheater as a whole has also been designated by the Province of Turin as a geo-site.[46] This recognition does not imply for now, as in the case of nature reserves, a direct protection of the area; however, the classification should be taken into consideration during urban planning, in the drafting of territorial planning documents and in the choice of tools for a possible tourist enhancement of the areas concerned.[47]

Tourism and sport

The area of the morainic amphitheater includes within it some popular tourist destinations such as Lake Viverone and Lake Sirio, around which a decent network of accommodation facilities such as campsites, hotels and restaurants of various kinds has long been developed. The waters of the two lakes are suitable for bathing and, in the case of Lake Viverone, a public boat line connects the main towns along the coast.

More recently, some initiatives to promote tourism of the amphitheater have been taken by the Ecomuseum of the Ivrea Morainic Amphitheater, a nonprofit association formed in 2008 and bringing together 14 municipalities in the area, the Piccolo Anfiteatro Morenico Canavesano hill community as well as various associations and private law entities. The Comunità Montana Val Chiusella, later dissolved in 2012, also participated in the initiative. In addition to the strictly museum activities, various types of events such as theater performances, concerts, seminars and thematic excursions are organized and/or promoted.[49]

In the area there are many marked hiking routes; the one most closely related to the geological conformation of the AMI is undoubtedly the Alta Via dell'Anfiteatro Morenico di Ivrea, whose main track, of about 120 km in length, runs entirely along the outer hilly circle of the AMI starting from Andrate and ending in Brosso. Accompanying the main track are several connecting routes that allow access to the main track from surrounding settlements. An extension of hiking in the area of the 5 lakes of Ivrea, some variants to the main trail and several thematic routes have also been marked. All of these routes can be traveled on foot or on horseback and, in general, also by mountain bike.[50] Another important hiking route that crosses the AMI in a north-south direction is the Via Francigena, which retraces the aforementioned route of the medieval pilgrims.[note 5] The northeastern part of the AMI is also affected by the GtB (Grande traversata del Biellese).

There are also numerous sporting events; of particular note is a classic of Piedmontese running, the 5 laghi, which reached its 33rd edition in 2010.[51] The competition, about 25 km in length, takes place in the area of the 5 lakes and transits for the most part on trails and dirt tracks. More closely related to the hiking trails seen above is the Morenic Trail, an individual or relay trail that runs for 109 km following the main trail of the Alta Via dell'Anfiteatro Morenico di Ivrea.[52]

Notes

- The northeastern strip of the AMI, centered on the municipal territories of Sala Biellese and Zubiena, is generally not considered part of Canavese but of Biella.

- The existence of a single lake basin extending over the entire area within the AMI, at least as far as the period following the Upper Pleistocene glacial expansion is concerned, is denied by modern geologists and, in particular, by studies published by Francesco Carraro in the 1980s.

- The western paleochannel of the Dora Baltea in its lower part is now occupied by the Rio Ribes, a left tributary of the Chiusella River.

- In particular, the two sites were analyzed in the 1970s by scholar R. Schneider

- The Canavese section of the Via Francigena has been reconstructed and marked by various local associations with the collaboration of the City of Ivrea and has been manned since 2009 by Sigerico's Via Francigena Association (The association's website Archived September 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine)

References

- "Il territorio". Comunità Collinare "Piccolo Anfiteatro Morenico Canavesano". Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- "Sito ufficiale della Regione Piemonte". Retrieved November 10, 2010.

- Scavini, Andrea (1998). "Piccoli grandi viaggi: la via Francigena all'ombra della Serra d'Ivrea". Piemonte Parchi. Archived from the original on June 7, 2012. Retrieved November 23, 2010.

- AA.VV. (2009). Aggiornamento e adeguamento del Piano Territoriale di Coordinamento Provinciale - Assetto geologico e geomorfologico. Torino: Provincia di Torino.

- Carta Tecnica Regionale raster 1:10.000 (vers.3.0) della Regione Piemonte - 2007

- "Geologia". Archived from the original on October 25, 2008. Retrieved November 23, 2010.

- Marazzi, Sergio (2005). Atlante Orografico delle Alpi. SOIUSA. Pavone Canavese: Priuli & Verlucca. ISBN 88-8068-273-3.

- "Il gran Canale Cavour e la precedente situazione irrigua piemontese". Consorzio Ovest Sesia. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- Direzione Pianificazione delle Risorse Idriche (2003). Atlante dei laghi Piemontesi. Regione Piemonte.

- Barengo, Livio (2002). Ypa, Morrigan salassa : il lago, l'oro, la vite : storia di Ypa e della sua gente. Aosta: Keltia. ISBN 88-7392-001-2.

- Azario, Pietro (1970). De bello canepiciano : la guerra del canavese. Translated by Vignono, Ilo; Monti, Pietro. Mercenesco: Tip. L. Marini.

- AA.VV. (2009). Studio di base per il Sito di Importanza Comunitaria (SIC) Laghi id Ivrea (PDF). WWF Italia. pp. 10–11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- Accotto, Secondo (2005). Piano regolatore generale comunale variante strutturale n° 5 - Verifica di compatibilità idraulica ed idrogeologica (PDF). Banchette: Comune di Banchette. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- Duregon, Corrado (2006). Carta Geologica dell'Anfiteatro Morenico della Serra. Borgaro: ATL 3 Canavese e Valli di Lanzo.

- Carraro Francesco; F.Medioli; F.Petrucci (1975). Geomorphological study of the morainic Amphiteatre of Ivrea, Northwest Italy. R. Soc. New Zealand.

- Gianotti, Franco (1993). Ricostruzione dell'evoluzione quaternaria del margine esterno del settore laterale sinistro dell'Anfiteatro Morenico d'Ivrea. Tesi di Laurea. Università di Torino.

- Assessorato alla Pianificazione Territoriale della Provincia di Biella (2004). "Fisiografia e pericolosità ambientale". Variante n.1 al Piano Territoriale Provinciale - Matrice ambientale (pdf). Archived from the original on May 5, 2014. Retrieved September 1, 2009.

- AA.VV. Genesi dell'anfiteatro di Ivrea (PDF). Provincia di Torino. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- Lauria Nicola; Leonardo Perona (2009). Relazione geologico-tecnica (PDF). Comune di Fiorano Canavese. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- "Il parco naturale del lago di Candia". Provincia di Torino. Archived from the original on December 1, 2010. Retrieved December 27, 2010.

- Ravazzi, Cesare. "Il Tardoglaciale: suddivisione stratigrafica, evoluzione sedimentaria e vegetazionale nelle Alpi e in Pianura Padana". Studi Trent. Sci. Nat., Acta Geol., 2005 (82): 17–29. ISSN 0392-0534

- "Insediamenti umani in Età Preistorica". Comune di Vialfrè. Archived from the original on June 7, 2008. Retrieved November 23, 2010.

- "Preistoria". Associazione Via Francigena. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- "Da Borgofranco ad Ivrea". Associazione Serramorena. Archived from the original on 6 September 2010. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- AA.VV. (2003). Biella e provincia: Candelo, Santuario di Oropa, Valle del Cervo, Oasi Zegna. Borgaro: Touring Editore.

- Cavallari-Murat, Augusto (1976). Tra Serra d'Ivrea, Orco e Po. Torino: Istituto bancario San Paolo di Torino.

- Marco Roggero. "Il complesso megalitico di Cavaglià, ricostruzione geometrica da fotografie storiche". Politecnico di Torino. Archived from the original on 14 July 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- "La via francigena di Sigerico". Archived from the original on 19 December 2010. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- AA.VV. (1995). Torino e Valle d'Aosta. Torino: Touring Editore.

- Strabone. Geografia - libro IV 6-7.

- Elisa Brunero. "Eporedia - città romana d'importanza strategica". Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- "Il paese di Strambino". Comune di Strambino. Archived from the original on April 9, 2010. Retrieved November 23, 2010.

- AA.VV. (1976). Piemonte. Milano: Touring Editore.

- Fiandro, Federico (2003). La storia del vino in Canavese. Santhià: GS editrice.

- Senatore, Fulvio. "Olivo in canavese: benvenuto o bentornato?". Associazione Piemontese Olivicoltori. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- "Cenni storici". ovestsesia.it. Consorzio Ovest Sesia. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- "Aspetti Storico Culturali". Comune di Cascinette di Ivrea. Archived from the original on June 21, 2012. Retrieved November 23, 2010.

- Marchisio, Matteo. "Erbaluce di Caluso: un bianco importante". laculturadelcibo.it. La cultura del cibo. Archived from the original on 10 May 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- "Strada del Vino del Canavese e Valli di Lanzo". Associazione Nazionale Città del Vino. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- "AMI - orografia, nuclei antichi ed espansioni recenti" (PDF). Osservatorio del Paesaggio AMI. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- Masuelli, Elena. "Alluvione 2000, dieci anni fa". La Stampa. Archived from the original on October 18, 2010. Retrieved November 23, 2010.

- "Il parco del Lago di Candia festeggia i 15 anni". Provincia di Torino. 2010. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- AA.VV. (2009). La rete Natura 2000 in Piemonte - I siti di importanza comunitaria. Savigliano: Regione Piemonte.

- "Ricerca le schede dei Siti di Importanza Comunitaria (SIC) in Piemonte". Archived from the original on 17 September 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- Deliberazione della Giunta Regionale 4 luglio 2016, n. 29-3572 (PDF). Regione Piemonte. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- AA.VV. (2004). I geositi nel paesaggio della Provincia di Torino. Nichelino: Litografia Geda.

- "Aggiornamento del PTCP (Piano Territoriale Di Coordinamento Provinciale) in materia di dissesto idrogeologico". Provincia di Torino. Archived from the original on 7 September 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- Ecomuseo dell'Anfiteatro Morenico di Ivrea. "Programma eventi 2010". Archived from the original on September 23, 2009. Retrieved November 23, 2010.

- Alta Via dell'Anfiteatro Morenico della Serra. San Mauro Torinese: ATL 3 Canavese e Valli di Lanzo. 2007.

- "Storia della gara". Archived from the original on 10 May 2010. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- "Percorso Sito della gara". Morenictrail. Archived from the original on 24 September 2010. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

Bibliography

- AA.VV. (2006). Carta Geologica dell'Anfiteatro Morenico della Serra. Borgaro: ATL 3 Canavese e Valli di Lanzo.

- AA.VV. (2004). L'anfiteatro morenico di Ivrea : un geosito di valore internazionale. Nichelino: Litografia Geda. Archived from the original (pdf) on June 12, 2009.

- AA.VV. (2009). La rete Natura 2000 in Piemonte - I siti di importanza comunitaria. Savigliano: Regione Piemonte. ISBN 978-88-904283-0-2.

- Antonicelli, Matteo; Biava Bertinatti, Stefano (2013). Anfiteatro Morenico di Ivrea. Guida all'Alta Via e alla Via Francigena Canavesana. Biella: Lineadaria Editore. ISBN 978-88-97867-17-3. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- Azario, Pietro (1970). De bello canepiciano : la guerra del canavese. Translated by Vignono, Ilo; Monti, Pietro. Mercenesco: Tip. L. Marini.

- Barengo, Livio (2002). Ypa, Morrigan salassa. Il lago, l'oro, la vite : storia di Ypa e della sua gente. Aosta: Keltia. ISBN 88-7392-001-2.

- Bolzon, Pio (1916). Nuovi materiali per la flora dell'anfiteatro morenico d'Ivrea. Aosta: Tipografia Cattolica.

- Bolzon, Pio (1915). Studio fitogeografico sull'anfiteatro morenico di Ivrea. Firenze: Pellas.

- Bruno, Luigi (1877). I terreni costituenti l'anfiteatro allo sbocco della Dora Baltea. Ivrea: Cubris.

- Carraro, Francesco; Petrucci, F. (1975). Dislocazioni recenti nell'Anfiteatro morenico d'Ivrea. Ateneo Parmense.

- Francesco, Francesco; Medioli, F.; Petrucci, F. (1975). Geomorphological study of the morainic Amphiteatre of Ivrea, Northwest Italy. R. Soc. New Zealand.

- De Agostini, Giovanni (1895). Le torbiere dell'anfiteatro morenico d'Ivrea. Ricci.

- De Agostini, Giovanni (1894). Scandagli e ricerche fisiche sui laghi dell'anfiteatro morenico d'Ivrea. Torino: Clausen.

- Direzione Pianificazione delle Risorse Idriche (2003). Atlante dei laghi Piemontesi. Regione Piemonte.

- Fiandro, Federico (2003). La storia del vino in Canavese. Santhià: GS editrice. ISBN 88-87374-80-5.

- Gallotti, Raffaella (1987). L'anfiteatro morenico d'Ivrea : caratteristiche e genesi. Pavia: Università degli Studi di Pavia - facoltà di Scienze Naturali.

- Gribaudi, Dino (1932). Sulla distribuzione dei centri abitati nell'anfiteatro morenico d'Ivrea. Dell'Erma.

- Lauria, Nicola (1990). Elementi geologici ed evoluzione del paesaggio del Canavese Orientale dalla fine dell'era Terziaria all'Olocene. Ivrea: Litografia Bolognino.

- Marco, Carlo (1893). Dalla scomparsa del mare pliocenico alla formazione dell'anfiteatro morenico della Dora Baltea con cenni sulla formazione dei ghiacciai alpini. Ivrea: Tomatis.

- Marco, Carlo (1892). Studio geologico dell'anfiteatro morenico d'Ivrea. Roux.

- Ravazzi, Cesare. "Il Tardoglaciale: suddivisione stratigrafica, evoluzione sedimentaria e vegetazionale nelle Alpi e in Pianura Padana" (PDF). Studi Trent. Sci. Nat., Acta Geol., 2005 (82): 17–29. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 12, 2020. Retrieved December 27, 2010.

- Sacco, Federico (1917). Escursione storico-geologico-tecnica nell'Anfiteatro morenico di Ivrea. Torino.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sacco, Federico (1927). Il glacialismo nella Valle d'Aosta. Parma: Cecchini.

- Schneider, R. "Pollenanalytische Untersuchungen zur Kenntnis der spät- und postglazialen Vegetationgeschichte am Südrand der Alpen zwischen Turin und Varese (Italien)". Botanische Jahrbücher für Systematik, Pflanzengeschichte und Pflanzengeographie; Leipzig, 1978 (100): 26–109.

- Tassoni, Mario (2011). L'Anfiteatro morenico di Ivrea, dalla Pera Cunca alla Olivetti. Cossano Canavese (TO): Alfredo Editore. ISBN 978-8896960073.