Empress Shōshi

Fujiwara no Shōshi (藤原彰子, 988 – October 25, 1074), also known as Jōtōmon-in (上東門院), the eldest daughter of Fujiwara no Michinaga, was Empress of Japan from c. 1000 to c. 1011. Her father sent her to live in the Emperor Ichijō's harem at age 12. Because of his power, influence and political machinations she quickly achieved the status of second empress (中宮, Chūgū). As empress she was able to surround herself with a court of talented and educated ladies-in-waiting such as Murasaki Shikibu, author of The Tale of Genji.

| Fujiwara no Shōshi | |

|---|---|

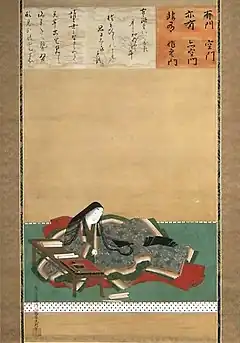

Fujiwara no Shōshi with her infant son Atsuhira is depicted in this 13th-century painting, with her father Fujiwara no Michinaga and lady-in-waiting Murasaki Shikibu presiding at the 50-day ceremony of the child's birth. | |

| Empress consort of Japan | |

| Tenure | 1000–1011 |

| Empress dowager of Japan | |

| Tenure | 1012–1018 |

| Grand empress dowager of Japan | |

| Tenure | 1018–1074 |

| Born | 988 |

| Died | October 25, 1074 (aged 86) |

| Spouse | Emperor Ichijō |

| Issue | Emperor Go-Ichijō Emperor Go-Suzaku |

| House | Fujiwara clan |

| Father | Fujiwara no Michinaga |

By the age of 20, she bore two sons to Ichijō, both of whom went on to become emperors and secured the status of the Fujiwara line. In her late 30s she took vows as a Buddhist nun, renouncing imperial duties and titles, assuming the title of Imperial Lady. She continued to be an influential member of the imperial family until her death at age 86.

Empress

In the middle of the 9th century Fujiwara no Yoshifusa declared himself regent to Emperor Seiwa—his young grandson—the Fujiwara clan dominated court politics until the end of the 11th century, through strategic marriages of Fujiwara daughters into the imperial family and the use of regencies. Fujiwara no Michinaga had four daughters he arranged to marry to emperors.[1] At this period emperors held little power, holding a nominal position for rituals, and often too young to make decisions. In their stead, the top position in the power structure was held by a regent, with power often measured by the how closely the regent was tied by family relationships to an emperor.[2] In 995 Michinaga's two brothers Fujiwara no Michitaka and Fujiwara no Michikane died in rapid succession, leaving the regency vacant; Michinaga won a power struggle against his nephew Fujiwara no Korechika, brother to Emperor Ichijō's wife Teishi, aided by his sister Senshi (mother to Emperor Ichijō, as Emperor En'yū's wife). Because Teishi supported Korechika—later discredited and banished from court—her base of power disintegrated.[3]

Four years later Michinaga sent Shōshi, his eldest daughter, to Emperor Ichijō's harem when she was about 12.[4][5] She became Imperial Consort, nyogo of the emperor. A year after placing Shōshi in the imperial harem, in an effort to undermine Teishi's influence and increase Shōshi's standing, Michinaga had her named Empress although Teishi already held the title. As historian Donald Shively explains, "Michinaga shocked even his admirers by arranging for the unprecedented appointment of Teishi (or Sadako) and Shōshi as concurrent empresses of the same emperor, Teishi holding the usual title of "Lustrous Heir-bearer" kōgō and Shōshi that of "Inner Palatine" (chūgū), a toponymically derived equivalent coined for the occasion".[3] She raised Imperial Prince Atsuyasu, Imperial Princess Shushi and Imperial Princess Bishi, the children of Empress Teishi until her son was born. She gave birth to Imperial Prince Atsuhira in 1008 and Imperial Prince Atsunaga in 1009.

She went on to hold the title(s) of Empress Dowager (Kōtaigō) and Grand Empress Dowager (Taikōtaigō).[6]

Ladies-in-waiting

To give Shōshi prestige and to make her competitive in a court that valued education and learning, Michinaga sought talented, educated and interesting ladies-in-waiting to build a salon to rival that of Teishi and Seishi (daughter of Emperor Murakami). Michinaga invited Murasaki Shikibu, author of The Tale of Genji, to Shōshi's court, where she joined Izumi Shikibu and Akazome Emon. Later Ise no Taifu, a talented poet and musician also joined. At Teishi's court as lady-in-waiting was writer Sei Shōnagon, author of The Pillow Book. The women at the two empresses' courts wrote some of the best-known and enduring Heian era literature.[7][8]

Although she lived in the Imperial palace, Shōshi's main residence for was in one or another of her father's many mansions, particularly after the Imperial palace burned down in 1005.[9] Shōshi was about 16 when Murasaki joined her court, probably to teach her Chinese. Japanese literature scholar Arthur Waley describes Shōshi as a serious young lady based on a passage from Murasaki who wrote in her diary: "As the years go by Her Majesty is beginning to acquire more experience of life, and no longer judges others by the same rigid standards as before; but meanwhile her Court has gained a reputation for extreme dullness, and is shunned by all who can manage to avoid it".[10] Moreover, Murasaki describes advice Shōshi gave to her ladies-in-waiting to avoid appearing too flirtatious:

Her Majesty does indeed still constantly warn us that it is a great mistake to go too far, 'for a single slip may bring very unpleasant consequences,' and so on, in the old style; but she now also begs us not to reject advances in such a way as to hurt people's feelings. Unfortunately, habits of long standing are not so easily changed; moreover, now that the Empress's exceedingly stylish brothers bring so many of their young courtier-friends to amuse themselves at her house, we have in self-defence been obliged to become more virtuous than ever'.[10]

Mother to two emperors

Shōshi gave Ichijō two sons, in 1008 and 1009. The births are described in detail in Murasaki's The Diary of Lady Murasaki. The boys were born at their grandfather's Tsuchimikado mansion, with Buddhist priests in attendance.[9][11] With her second son Atsuhira, Shōshi had a difficult birth; to appease evil spirits she underwent a ritual head shaving, although only a lock of hair was cut.[12] This ritual was considered to have been a minor ordination, or jukai into Buddhism, for the purpose of receiving divine protection when her life, and that of her unborn infant, was at risk.[6]

Ritual ceremonies were followed on specific days after the births. As was customary, Michinaga's first visit to Shōshi took the form of a lavish ritual 16 days after she gave birth.[11] In her diary, Murasaki described the clothing of one woman in attendance, "Her mantle had five cuffs of white lined with dark red, and her crimson gown was of beaten silk".[13] On the 50th day after the birth a ceremony was held in which the infant was offered a piece of mochi; Michinaga performed the ritual offering of the rice cake to his grandson Atsuhira. In her diary Murasaki described the event that she probably attended.[14]

Michinaga's influence meant that Shōshi's two sons had a better chance of ascending the throne than Teishi's children—particularly after Teishi's death in 1001.[3] When Ichijō abdicated in 1011 and died soon after,[15] Shōshi's eldest son, the future Emperor Go-Ichijō, was named crown prince.[3] At that time Shōshi retired from the Imperial Palace to live in a Fujiwara mansion in the Lake Biwa region, most likely accompanied by Murasaki.[16] In 1016 when Michinaga had Emperor Sanjō—married to Shōshi's younger sister Kenshi—removed from the throne, Go-Ichijō became emperor. Shōshi's second son, Go-Suzaku, became crown prince in 1017. With an emperor and a crown prince as sons, Shōshi's position was secure and she became a powerful influence at court.[4]

For many years Shōshi's power extended to selecting friends and relatives to fill court positions and to approving consorts—decisions that affected the imperial court. The consorts she selected were her father's direct descendants, thus she asserted control of her father's lineage for many years.[15]

Imperial Lady

It was not uncommon for Heian aristocratic women to take religious vows, become nyūdō, and yet remain in secular life. As her father and her aunt Seishi had done before her, at 39 in 1026, Shōshi underwent an ordination ceremony to become a Buddhist nun. This was done at a lavish ceremony, at a place decorated with gold-leafed illustrated folding screens, priceless gifts were displayed, and courtiers, dressed in sumptuous costumes, were in attendance. The ritual was performed by five priests, three representing the most senior hierarchy of the Buddhist priesthood, one of whom was Shōshi's cousin who performed the hair-cutting ceremony, in which her long hair was cut shoulder-length, called amasogi style. At this time she assumed the name Jōtōmon-in. This, her second jukai, symbolized a transition from Empress to Imperial Lady, a change of lifestyle, and marked her as a novice nun. However, research suggests that political power was gained rather than lost when becoming Imperial Ladies, despite relinquishing imperial duties and devoting themselves to Buddhist rites. As was the custom for noblewomen of her period, Shōshi took ordination rites in steps; much later in life, in yet another ritual, she received full vows and at that time underwent a full shaving of her head.[6]

The first two empresses to take title of Imperial Lady were Seishi, later followed by Shōshi. With the title came a new residence and permission to hire men for the household. Shōshi's role as Imperial Lady, as documented in the Eiga Monogatari, was studied and emulated by imperial women who were to follow her as Imperial Ladies.[17]

She died in 1074 aged 86.[4]

References

- Henshall (1999), 24–25

- Bowring (2005), xiv

- Shively and McCullough (1999), 67–69

- McCullough (1990), 201

- Bowring believes she was 10 years old when she was sent to court. See Bowring (2005), xiv

- Meeks, 52–57

- Shirane (1987), 58

- Mulhern (1994), 156

- Bowring (2005), xxiv

- Waley (1960), viii

- Mulhern, (1991), 86

- Groner (2002), 281

- qtd in Mulhern, (1991), 87

- "Detached segment of the diary of Lady Murasaki emaki". National Treasures and Important Cultural Properties of National Museums, Japan. National Institutes of Cultural Heritage. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- Adolphson (2007), 31

- Shirane (1987), 221

- Meeks, 58

Sources

- Adolphson, Mikhael; Kamens, Edward and Matsumoto, Stacie. Heian Japan: Centers and Peripheries. (2007). Honolulu: Hawaii UP. ISBN 978-0-8248-3013-7

- Bowring, Richard John (ed). "Introduction". in The Diary of Lady Murasaki. (2005). London: Penguin. ISBN 9780140435764

- Groner, Paul. Ryōgen and Mount Hiei: Japanese Tendai in the tenth century. (2002). Kuroda Institute. ISBN 978-0-8248-2260-6

- Henshall, Kenneth G. A History of Japan. (1999). New York: St. Martin's. ISBN 978-0-312-21986-4

- Meeks, Lori. "Reconfiguring Ritual Authenticity: The Ordination Traditions of Aristocratic Women in Premodern Japan". (2006) Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. Volume 33, Number 1. 51–74

- McCullough, Helen. Classical Japanese Prose: An Anthology. (1990). Stanford CA: Stanford UP. ISBN 978-0-8047-1960-5

- Mulhern, Chieko Irie. Heroic with Grace: Legendary Women of Japan. (1991). Armonk NY: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-87332-527-1

- Mulhern, Chieko Irie. Japanese Women Writers: a Bio-critical Sourcebook. (1994). Westport CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-25486-4

- Shirane, Haruo. The Bridge of Dreams: A Poetics of "The Tale of Genji". (1987). Stanford CA: Stanford UP. ISBN 978-0-8047-1719-9, 58

- Shively, Donald and McCullough, William H. The Cambridge History of Japan: Heian Japan. (1999). Cambridge UP. ISBN 978-0-521-22353-9

- Waley, Arthur. "Introduction". in Shikibu, Murasaki, The Tale of Genji: A Novel in Six Parts. translated by Arthur Waley. (1960). New York: Modern Library.