John Newlands (chemist)

John Alexander Reina Newlands (26 November 1837 – 29 July 1898) was a British chemist who worked concerning the periodicity of elements.

John Newlands | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 26 November 1837 Lambeth, London, England |

| Died | 21 July 1898 (aged 60) Lower Clapton, Middlesex, England |

| Alma mater | Royal College of Chemistry Imperial College London |

| Known for | Periodic table, law of octaves |

| Awards | Davy Medal (1887) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Analytical chemistry |

Biography

Newlands was born in London in England, at West Square in Southwark, the son of a Scottish Presbyterian minister and his Italian wife.[1]

Newlands was home-schooled by his father, and later studied at the Royal College of Chemistry, now part of Imperial College London. He was interested in social reform and during 1860 served as a volunteer with Giuseppe Garibaldi in his military campaign to unify Italy.[2] Returning to London, Newlands established himself as an analytical chemist in 1864. In 1868 he became chief chemist of James Duncan's London sugar refinery, where he introduced a number of improvements in processing. Later he quit the refinery and again became an analyst with his brother, Benjamin.

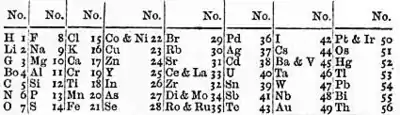

Newlands was the first person to devise a periodic table of chemical elements arranged in order of their relative atomic masses[3] published in Chemical News in February 1863.[2][4] Continuing Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner's work with triads and Jean-Baptiste Dumas' families of similar elements, he published in 1865 his "Law of Octaves", which stated that "any given element will exhibit analogous behaviour to the eighth element following it in the table." Newlands arranged all of the known elements, starting with hydrogen and ending with thorium (atomic weight 232), into eight groups of seven, which he likened to octaves of music.[5][6] In Newlands' table, the elements were ordered by the atomic weights that were known at the time and were numbered sequentially to show their order. Groups were shown going across the table, with periods going down – the opposite from the modern form of the periodic table.

The incompleteness of the table alluded to the possible existence of additional, undiscovered elements. However, the Law of Octaves was ridiculed by some of Newlands' contemporaries, and the Society of Chemists did not accept his work for publication.[7]

After Dmitri Mendeleev and Lothar Meyer received the Davy Medal from the Royal Society for their later 'discovery' of the periodic table in 1882, Newlands fought for recognition of his earlier work and eventually received the Davy Medal in 1887.

John Newlands died due to complications of surgery at his home in Lower Clapton, Middlesex and was buried at West Norwood Cemetery. His businesses was continued after his death by his younger brother, Benjamin.

Works

- On the discovery of the periodic law, and on relations among the atomic weights. London: Spon. 1884.

See also

References

- 'Newlands, Newlands, John Alexander Reina' by Michael A. Sutton, Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 515.

- Like many of his contemporaries, Newlands first used the terms "equivalent weight" and "atomic weight" without any distinction of meaning and in his first paper during 1863. He used the values accepted by his predecessors. It is now referred to as "standard atomic weight".

- Newlands, John A. R. (7 February 1863). "On Relations Among the Equivalents". Chemical News. 7: 70–72.

- Newlands, John A. R. (20 August 1864). "On Relations Among the Equivalents". Chemical News. 10: 94–95.

- Newlands, John A. R. (18 August 1865). "On the Law of Octaves". Chemical News. 12: 83.

- Bryson, Bill (2004). A Short History of Nearly Everything. London: Black Swan. pp. 141–142. ISBN 978-0-552-15174-0.

Further reading

- Scerri, Eric R. (2007). The periodic table: Its story and its significance. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-19-530573-9.