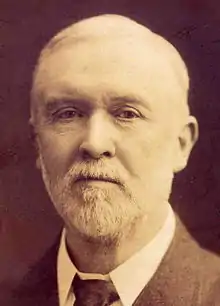

J. J. Clancy (North Dublin MP)

John Joseph Clancy (15 July 1847 – 25 November 1928), usually known as J. J. Clancy, was an Irish nationalist politician and Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons for North Dublin from 1885 to 1918. He was one of the leaders of the later Irish Home Rule movement and promoter of the Housing of the Working Classes (Ireland) Act 1908, known as the Clancy Act. Called to the Irish Bar in 1887, he became a King's Counsel in 1906.[1]

Origins

Son of a farmer, William Clancy of Carraghy, J. J. Clancy was born at the height of the Great Irish Famine in the parish of Annaghdown, County Galway, which was one of the worst affected areas. He was educated at the College of the Immaculate Conception, Athlone, and at the recently founded non-sectarian Queen's College, Galway, obtaining an MA in Ancient Classics in 1868. At both institutions he was a contemporary of his later parliamentary colleague, T. P. O'Connor.

Clancy spent three years as a Classics teacher at Holy Cross School, Tralee, where he married Margaret Louise Hickie (d. 1912) of Newcastle West, County Limerick, in 1868. She was from a strongly Nationalist family and one of her nephews was the Irish revolutionary and author Piaras Béaslaí, who had close relations with the Clancy family.

Early political life

In 1870, J. J. Clancy took up the post of assistant editor of the leading Nationalist weekly The Nation, acting as editor in 1880–85. During this time he was a Council member of the Home Rule League and active in the Young Ireland Society. He organised a vigorous voter registration campaign in County Dublin after the Nationalist defeat at a by-election in 1883, and was elected MP for the North seat in the Nationalist landslide December 1885 general election.

Clancy was appointed by the Irish Party in 1886 as editor of the Irish Press Agency in London, whose purpose was to win support for Irish Home Rule in Great Britain. In this role he wrote or edited dozens of pamphlets, many of them attacking the regime of coercion introduced by Arthur Balfour as Chief Secretary for Ireland after the Conservative Party returned to power in 1886.

Parnell split

Clancy had long been a strong supporter of the Irish leader Charles Stewart Parnell. When a majority of the Irish Parliamentary Party turned against Parnell in November 1890, following what amounted to a demand by the Liberal leader, Gladstone, that Parnell should stand down over his involvement with Katharine O'Shea, Clancy rapidly emerged as one of Parnell's key defenders. On the third day of the Irish Party's week-long debate on Parnell's leadership in Committee Room 15 of the House of Commons, Clancy proposed an amendment that attempted to compromise by seeking further views from Gladstone and the other British Liberal Party leaders. Although this move held off a decision for another three days, it was ultimately unsuccessful. Clancy was among the minority who stayed with Parnell when the party split on 6 December 1890 into the pro-Parnellite Irish National League (INL) and the anti-Parnellite Irish National Federation (INF). He later joined the editorial staff of the Irish Daily Independent, founded to support the Parnellite cause.

After Parnell's death in October 1891, the Parnellites were in an isolated position. At the July 1892 general election they faced vigorous opposition from the Catholic Church and Clancy was one of only nine INL Parnellites elected. Thereafter he worked closely with John Redmond, who led the small Parnellite group and after the 1900 general election the re-united Irish Parliamentary Party. Together with fellow Parnellites Willie Redmond and Pat O'Brien, Clancy was one of the small core of Redmond's confidants, and until Redmond's death in March 1918 was his most trusted adviser on legal draftsmanship and constitutional law. After the retirement of Thomas Sexton, Clancy was seen as the Irish Party's financial expert.

Reforming legislation

Following the overwhelming rejection of the second Irish Home Rule Bill by the House of Lords in 1893 and the Conservatives' return to power in 1895 general election, immediate prospects for Home Rule were abandoned. Over the next 15 years, Clancy focused on making the most of opportunities for reform. He helped in the framing of the various Land Acts, which settled the land question by enabling tenant farmers to buy their holdings, publishing a guide to the Land Act of 1896. He supported the introduction of democratic local government in Ireland following the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898 by publishing a guide to the Act and editing the County Councils Gazette. He acted as spokesman for the Irish Party in support of the Trade Disputes Bills of 1904 and 1906 that restored the effective right to strike—which had been undermined by the Taff Vale Case of 1901.

After the Liberals' return to office in the 1906 general election, Clancy helped get inscribed on the Statute Book Acts of considerable importance.[2] He played a major role in promoting the Town Tenants (Ireland) Act of 1906, which gave rights to urban tenants to retain the value of their improvements parallel to those the Land Acts extended to farmers. Housing conditions in Ireland at the time were very poor, and Clancy's 1908 Housing Act, known as the Clancy Act made various financial and administrative changes with the aim of speeding up the building of council housing. The Clancy Act created a boom in urban social housing in Ireland.[3] Clancy also contributed to the resolution of the Catholic University question, via the Act of 1908 that established the present National University of Ireland, which removed barriers that had held back participation in higher education by Ireland's Catholic majority.

Third Home Rule Bill

Attaining Home Rule for Ireland by constitutional means required overcoming opposition from the House of Lords. This opportunity arose as a result of David Lloyd George's 1909 budget, which the Lords attempted to veto, leading the Liberals to fight a general election in 1910 on a platform of limiting the power of the Lords. But the 1909 budget was also unpopular in Ireland, because of changes to alcohol taxes and death duties, the latter affecting the very farmers whom the Irish Party itself had successfully campaigned to make owners of their farms. A delicate balance needed to be trodden and it fell to Clancy, by now the Irish Party's finance spokesman, to deal with the problem.

The Government of Ireland Act 1914, creating a settlement for Ireland similar to the later devolution arrangements for Scotland of 1998, eventually received the royal assent on 18 September 1914. But this was after earlier vehement Unionist opposition had become apparent in Ulster, featuring the Larne gun-running and near-mutiny in the British army. Implementation of the Act was postponed until after the First World War, which began on 4 August.

Rise of Sinn Féin

Following the Easter Rising of 1916, misjudgments by the British government bolstered support for Sinn Féin, the broad movement campaigning for an independent Republic, and events slipped out of the Irish Parliamentary leaders' control. The younger generation had been brought up in a greatly intensified atmosphere of cultural nationalism focusing particularly on militant separatism.

Clancy was one of five Irish Parliamentary Party representatives in the Irish Convention of 1917–18 who tried to get an agreed settlement of the Ulster question. In this capacity he took the majority Nationalist line, compromising over the question of customs and excise and safeguards for Protestant interests for the sake of agreement with the Southern Unionists, and rejecting the more assertive Nationalist line of a group led by the Bishop of Raphoe. Although the Convention produced a majority report, the consensus did not include the Northern Protestants and Lloyd George subsequently went ahead with legislation for partition under the Fourth Home Rule Act. Following Redmond's death in March 1918, Clancy was seen as the leader of the remnants of the Redmondite wing of the Party. He was one of the committee of six who drafted the Irish Parliamentary Party manifesto for the 1918 general election. In that election he was defeated by more than two to one by the Sinn Féin candidate, Frank Lawless, the Parliamentary Party swept aside and only winning a disproportionate six contested seats, on 21.7% of the national vote in Ireland.

J. J. Clancy died in Dublin on 25 November 1928.[4]

Notes

- "Clancy, John Joseph". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- Sheehan, D. D., Ireland since Parnell, p. 196, Daniel O'Connor, London (1921)

- Potter, Matthew, The Municipal Revolution in Ireland Urban Government in Ireland Since 1800 p.209, Irish Academic Press Dublin (2011) ISBN 978-0-7165-3082-4

- The Times, Obituary of J. J. Clancy KC, 27 November 1928, Irish Independent, Obituary of J. J. Clancy KC, 26 November 1928

Selected writings

- Essays and Speeches on the Irish Question: Vol. 1, edited by J. J. Clancy, London, Irish Press Agency, 1888

- ‘The Position of the Irish Tenant’, Contemporary Review, Vol.LVI, July 1889

- Short Lessons on the Irish Question; or, The leaflets of the Irish Press Agency, Vol.1, Nos.1–102, edited by J. J. Clancy, London, Irish Press Agency, 1890

- ‘The Question of the Irish Leadership’, Contemporary Review, Vol.LIX, March 1891

- ‘The Financial Aspects of Home Rule’, Contemporary Review, Vol.LXIII, January 1893

- ‘The Housing Problem: How to Solve It’, Speech delivered at the meeting of the Central branch of the United Irish League on 6 Nov 1907, Dublin, United Irish League, 1907

- The Irish Party and the Budget: A Vindication, Dublin, Sealy, Bryers and Walker, 1910

- The Home Rule Act: A Statement of its Provisions, Dublin, United Irish League, 1917

References

- Bew, Paul (1987), Conflict and Conciliation in Ireland 1890–1910: Parnellites and Radical Agrarians, Oxford, Clarendon Press

- Callanan, Frank (1992) The Parnell Split 1890–91, Cork University Press

- Freeman's Journal, 12–15 October 1881, 7–20 October 1882, 4 December 1885, 29 December 1911

- Gwynn, Stephen (1919), John Redmond's Last Years, London, Edward Arnold

- Hansard, Parliamentary Debates, 1886–1918

- Kennedy, Liam et al. (1999) Mapping the Great Irish Famine: A Survey of the Famine Decades, Dublin, Four Courts Press

- Lyons, F.S.L. (1951), The Irish Parliamentary Party 1890–1910, London, Faber (republ. Westport, Connecticut, Greenwood Press, 1975)

- Maume, Patrick (1999), The Long Gestation: Irish Nationalist Life 1891–1918, Dublin, Gill & Macmillan

- Mc Dowell, R. B. (1970), The Irish Convention 1917–18, London, Routledge

- O'Brien, Conor Cruise (1957), Parnell and His Party 1880–90, Oxford, Clarendon Press

- Béaslaí, Piaras papers, National Library of Ireland

- Sheehan, Daniel Desmond (1921), Ireland Since Parnell, London, Daniel O'Connor

- The Times (1891) "The Parnellite Split: or, The Disruption of the Irish Parliamentary Party", from The Times, with an Introduction, London

- Jackson, Alvin (2003), Home Rule: An Irish History 1800–2000, Weidenfeld & Nicolson

External links

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by J. J. Clancy

- John Redmond's Last Years by Stephen Lucius Gwynn at Project Gutenberg

- Ireland Since Parnell by D. D. Sheehan at Project Gutenberg

- Parnell’s visit to Ennis, Co. Clare in 1891

- Cartoon relating to J. J. Clancy’s sharing a platform with D. D. Sheehan in 1907