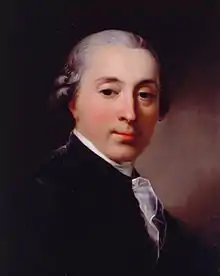

Jean Senebier

Jean Senebier (6 or 25 May 1742 – 22 July 1809[1][2]) was a Genevan Calvinist pastor and naturalist. He was chief librarian of the Republic of Geneva. A pioneer in the field of photosynthesis research, he provided extensive evidence that plants consume carbon dioxide and produced oxygen. He also showed a link between the amount of carbon dioxide available and the amount of oxygen produced and determined that photosynthesis took place at the parenchyma, the green fleshy part of the leaf.

Jean Senebier | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 6 or 25 May 1742 |

| Died | 22 July 1809 (aged 67) Geneva, Napoleonic Swiss Confederation |

| Nationality | Genevan |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Plant physiology, photosynthesis |

Biography

Senebier was born in Geneva, the son of a wealthy merchant.[3] He wrote extensively on plant physiology and was one of the major early pioneers of photosynthesis research.[4] Senebier also published on the experimental method, first in 1775,[5] and then in an expanded work, in 1802.[6] His precise definition of the experimental method anticipated the work of noted French physiologist Claude Bernard fifty years later.[7] Senebier also served as chief librarian of the Republic of Geneva.[3]

Senebier was greatly influenced by Swiss naturalist Charles Bonnet. Senebier was also influenced by the Italian animal physiologist and experimental biologist Lazzaro Spallanzani, several of whose works Senebier translated from Italian into French. Spallanzani's chemical research on bodily functions of animals helped lead Senebier towards studying plant chemistry. Although Senebier's first research on plants was a large study on effects of light, he is remembered mainly for the extensive evidence he provided that carbon dioxide ("fixed air" or "carbonic acid," in the terminology of his day) is consumed by plants in the production of oxygen ("dephlogisticated air"), in the physiological process that later became known as photosynthesis.[8][9] Senebier also found that the amount of oxygen produced is roughly proportional to the amount of carbon dioxide available to the plant.[9] Further, he determined that the green fleshy parts of leaves (the parenchyma) are the sites where carbon dioxide is transformed into oxygen.[8] Senebier also correctly concluded that plants use the carbon in carbon dioxide as a nutriment.[9] Senebier did some of his research[10] jointly with fellow Swiss naturalist François Huber.

Senebier arrived at his best known achievement, his demonstration that plants take up atmospheric carbon dioxide and give off oxygen, based entirely on the Phlogiston theory of chemistry, and only in his later works[11][12] did he reformulate his conclusions in terms of the more modern, oxygen chemistry developed by Antoine Lavoisier and colleagues.[13] This discovery by Senebier regarding gases ranks as one of the last of the important early discoveries in the unraveling of the fundamental chemical processes of photosynthesis. Marcello Malpighi and Nehemiah Grew, working independently in the late seventeenth century, and Stephen Hales in the early eighteenth century, had provided evidence that the atmosphere was important to plants,[4] but further progress in understanding the role of gases in plant physiology awaited discoveries made between 1750 and 1780. In 1754, Charles Bonnet reported that leaves that were plunged in aerated water produced bubbles of gas,[14] but he did not identify the gas. Then, in 1775, English chemist Joseph Priestley discovered oxygen (which he named "dephlogisticated air"),[15] and, just a few years later, in 1779, Dutch physician and researcher Jan Ingenhousz demonstrated that the bubbles of gas observed by Bonnet on submerged leaves consisted of this same gas. Ingenhousz also published the first convincing evidence that leaves produce this gas only in sunlight.[16]

Senebier was a close friend of noted Genevan geologist and meteorologist Horace-Bénédict de Saussure and was instrumental in the education of Horace-Bénédict's son Nicolas-Théodore de Saussure. Senebier trained the young man in Lavoisier's system of chemistry, which Nicolas-Théodore later applied in important plant-nutrition studies of his own.[13]: 180 The younger Saussure would eventually discover the role of water in photosynthesis, thus completing the early chemical research on this subject.[17]

In April 1809, Senebier became a Correspondent of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.[18]

For more detailed information on Senebier, see Kottler[13] and Nash.[19]

The standard botanical author abbreviation Seneb. is applied to species Senebier described.

Works

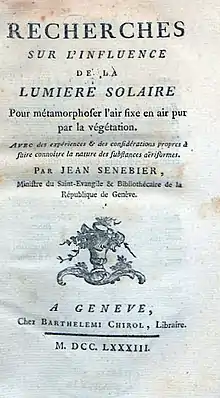

- Recherches sur l'influence de la lumiere solaire pour métamorpher l'air fixe en air pur par la végétation (in French). Genève: Chirol Barthelemi. 1783.

- Expériences sur l'action de la lumière solaire dans la végétation (in French). Genève: Manget Barde & C. 1788.

- Météorologie pratique a l'usage de tous les hommes, et sourtout des Cultivateurs (in French). Paris: Jean Jacques Paschoud. 1810.

References

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Senebier, Jean, in the Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Bay, J. Christian (1931). "Jean Senebier". Plant Physiology. 6 (1): 188–193. doi:10.1104/pp.6.1.188. PMC 441368. PMID 16652699.

- Hill, Jane (2012). "Chapter 30: Early Pioneers of Photosynthesis Research". In Eaton-Rye, Julian J.; Sharkey, Thomas D.; Tripathy, Baishnab C. (eds.). Photosynthesis: Perspectives on Plastid Biology, Energy Conversion and Carbon Metabolism. Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration, Vol. 34. Dordrecht, Heidelberg, London, New York: Springer. pp. 771–800.

- Senebier, Jean (1775). L'Art d'observer [The art of observing] (in French). Geneva: chez Cl. Philibert & Bart. Chirol. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- Senebier, Jean (1802). Essai sur l'art d'observer et de faire des experiences [Essay on the art of observing and making experiments] (in French). Geneva: J.J. Paschoud, Libraire. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- Pilet, P.E. (1975). ""Senebier, Jean"". In Gillispie, C.C. (ed.). Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. XII. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. pp. 308–309.

- Senebier, Jean (1782). Mémoires physico-chymiques sur l'influence de la lumière solaire pour modifier les êtres des trois règnes de la nature, & sur-tout ceux du règne vegetal, 3 vols [Physicochemical memoires on the influence of sunlight on the modification of the beings of the three kingdoms of nature, and above all those of the vegetable kingdom] (in French). Geneva: Chez Barthelemi Chirol. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- Senebier, Jean (1783). Recherches sur l'influence de la lumière solaire pour métamorphoser l'air fixe en air pur par la végétation [Research on the influence of solar light on the metamorphosis of fixed air into pure air by plants] (in French). Geneva: Chez Barthelemi Chirol. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

Senebier, Recherches sur l'influence de la lumière solaire pour métamorphoser l'air fixe en air pur par la végétation.

- Huber, François; Senebier, Jean (1801). Mémoires sur l'influence de l'air et de diverses substances gazeuses dans la germination de différentes grains [Memoirs on the influence of air and various gaseous substances on the germination of different seeds] (in French). Geneva: Chez J. J. Paschoud. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- Senebier, Jean (1791). Physiologie végétale. In Encyclopédie méthodique [Plant Physiology] (in French). Paris: Panckoucke. ISBN 9781277658293.

- Senebier, Jean (1800). Physiologie végétale, 5 vols [Plant Physiology] (in French). Geneva: Chez J. J. Paschoud. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- Kottler, Dorian B. (1973). Jean Senebier and the Emergence of Plant Physiology, 1775–1802: From Natural History to Chemical Science (Thesis). Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD. p. 12.

- Bonnet, Charles (1754). Recherches sur l'usage des feuilles dans les plantes [Research on the use of leaves in plants] (in French). Göttingen and Leiden: Chez Elie Luzac, fils. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- Priestley, Joseph (1775). "An account of further discoveries in air. Letters to Sir John Pringle". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 65: 384–394. doi:10.1098/rstl.1775.0039.

- Ingen-Housz, Jan (1779). Experiments upon vegetables, discovering their great power of purifying the common air in the sun-shine, and of injuring it in the shade and at night, to which is joined, a new method of examining the accurate degree of salubrity of the atmosphere. London: Elmsly and Payne. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- Hill, Jane F.; de Saussure, Theodore (2013). "Translator's Introduction". Chemical research on plant growth: A translation of Nicolas-Théodore's Recherches chimiques sur la Végétation. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4614-4136-6. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- "J. Senebier (1742–1809)". Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- Nash, Leonard K. (1952). Plants and the Atmosphere; Case 5, Harvard Case Histories in Experimental Science. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674673014.

- Sachs, Geschichte d. Botanik, and Arbeiten, vol. ii.

- Legée, G (1991), "[Physiology in the work of Jean Senebier (1742–1809)]", Gesnerus, vol. 49 Pt 3–4, pp. 307–22, PMID 1814778

- Marx, J (1974), "L'art d'observer au XVIIIe siècle: Jean Senebier et Charles Bonnet.", Janus; revue internationale de l'histoire des sciences, de la médecine, de la pharmacie, et de la technique, vol. 61, no. 1, 2, 3, pp. 201–20, PMID 11615396

- Bay, J C (1931), "JEAN SENEBIER", Plant Physiol. (published January 1931), vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 188–93, doi:10.1104/pp.6.1.188, PMC 441368, PMID 16652699