Ja'far al-Askari

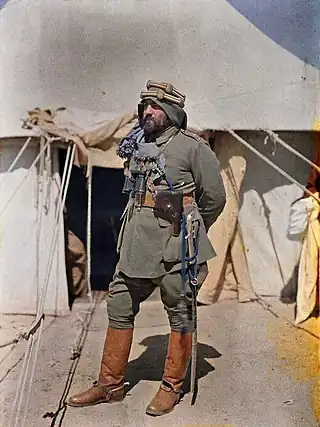

Ja'far Pasha al-Askari (Arabic: جعفر باشا العسكري, Ja‘far Bāsha al-‘Askari; 15 September 1885 – 29 October 1936) was an Iraqi politician who served twice as Prime Minister of Iraq in 1923–1924 and again in 1926–1927.

Ja'far Pasha al-Askari جعفر باشا العسكري | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prime Minister of Iraq | |

| In office 22 November 1923 – 3 August 1924 | |

| Monarch | Faisal I |

| Preceded by | Abd al-Muhsin as-Sa'dun |

| Succeeded by | Yasin al-Hashimi |

| In office 21 November 1926 – 11 January 1928 | |

| Monarch | Faisal I |

| Preceded by | Abd al-Muhsin as-Sa'dun |

| Succeeded by | Abd al-Muhsin as-Sa'dun |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 15 September 1885 Kirkuk, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 29 October 1936 (aged 51) Baghdad, Kingdom of Iraq |

Al-Askari served in the Ottoman Army during World War I until he was captured by British forces. After his release, he was converted to the cause of Arab nationalism and joined forces with Faisal I and Lawrence of Arabia with his brother-in-law, Nuri al-Said, who also served as Prime Minister of Iraq. Al-Askari took part in the capture of Damascus in 1918 and supported Faisal's bid for the Syrian throne. When Faisal was deposed by the French in 1920, al-Askari supported his bid for the Iraqi throne.

As a reward for his loyalty, Faisal granted al-Askari several important cabinet positions, including Minister of Defense in the first Iraqi government, as well as Minister of Foreign Affairs. Al-Askari served as Prime Minister twice. Al-Askari was assassinated during the events of the 1936 Iraqi coup d'état, in which Chief of Staff Bakr Sidqi overthrew the government. At the time, he was serving as Minister of Defense in Yasin al-Hashimi's government.

Early life and Ottoman Army career

Ja'far Pasha al-Askari was born on 15 September 1885 in Kirkuk, when it was still part of the Ottoman Empire. The fourth of five brothers and one sister, al-Askari's family was of Kurdish origin.[1] His father, Mustafa Abdul Rahman al-Mudarris, was a colonel in the Ottoman Army. Al-Askari attended the Military College in Baghdad before transferring to the Ottoman Military College in the Constantinople, where he graduated in 1904 as a Second Lieutenant. He was then sent to the Sixth Army, stationed in Baghdad. Al-Askari was then sent to Berlin from 1910 to 1912 to train and study as part of an Ottoman initiative to reform the army through the selection of officers via competition. Al-Askari stayed in this program until ordered back to the Ottoman Empire to fight in the Balkan Wars.[2]: 1–3

After the end of the Balkan Wars in 1913, al-Askari was made an instructor at the Officer Training College in Aleppo, but eight months later passed the qualifications for the Staff Officers' College in Constantinople.[2]: 4

World War I and the Arab Rebellion

When World War I broke out, al-Askari first fought on the side of the Ottomans and the Triple Alliance in Libya. His campaign started in the Dardanelles, after which he received the German Iron Cross and was promoted to General. After his promotion, he was sent to command the Senoussi Army in Libya. At the Battle of Agagia, al-Askari was captured by the British-led forces and imprisoned in a citadel in Cairo with his friend, and later brother-in-law, Nuri al-Said. Al-Askari made one escape attempt by fashioning a rope out of blankets to scale the citadel walls. During this attempt, the blanket tore and al-Askari fell, breaking his ankle and leading to his capture by the guards. According to his obituary, al-Askari offered to pay for the blanket, as he was on friendly terms with his captors.[2]: 100–103, 216–217, 273

Sometime after his escape attempt, al-Askari learned about the nationalist Arab Revolt against the Ottomans led by the Hashemite leader of the Hijaz, Hussein bin Ali, the Sharif of Mecca. This revolt had been sponsored by the British and the Triple Entente to weaken the Ottoman Empire. In exchange, the British had promised, during the McMahon–Hussein Correspondence, to create an Arab country led by Hussein. Upon learning about the Arab Revolt, and due to an increasingly hostile Ottoman approach to Arab affairs as embodied by the execution of a number of prominent Arabs for nationalist activities by Jamal Pasha, al-Askari decided that this was precisely in line with beliefs he had and decided to join the Hashemite Revolt along with Nuri al-Said. At first, Sharif Hussein was hesitant to let al-Askari, a former general in the Ottoman army, join his forces, but eventually relented, and al-Askari was invited by Hussein's son, Prince Faisal, to join in the fight against the Ottoman Empire. Al-Askari fought under Prince Faisal throughout this period up until the fall of the Ottoman Empire, and participated in Faisal's assault on Damascus in 1918.[2]: 5–6, 103–112, 217

Governor of Aleppo and Iraqi nationalism

After World War I and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, another of Hussein's sons, Prince Zeid, asked al-Askari on behalf of Prince Faisal to be the Inspector General of the Army of the newly established Kingdom of Syria, which he accepted. Shortly thereafter, al-Askari was appointed the Military Governor of the Aleppo Vilayet in Syria. During his time as governor in Syria, al-Askari heard from Iraqis about the status of their country during British rule. Al-Askari advocated the idea that Iraqis could take charge of their own country and could govern it better than the British. Al-Askari was in favor of a Hashemite ruler for Iraq with ties to Britain; he joined his friend Nuri al-Sa’id in the al-‘Ahd group that was in favor of ties to Britain.[3]: 36 [2]: 161–162, 173–175

Establishment of Iraq and political career

In 1921, the British set up an Arab government in Iraq and chose Prince Faisal, the son of Sharif Hussein, to be King. Faisal had never even been to Iraq, and so chose certain commanders familiar with the area to fill various posts, including al-Askari, who was appointed Minister of Defense. During this period, al-Askari arranged the return of 600 Iraqi Ottoman soldiers to form the Officer Corps of the new Iraqi army.[3]: 47 [4]: 128–129

In November 1923, King Faisal appointed al-Askari as Prime Minister of Iraq. Faisal wanted a strong supporter of the King to be Prime Minister during this key time when the Constituent Assembly opened in March 1924. The dominant issue during this assembly was the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty, put forward by the British to legitimize the Mandate for Mesopotamia. Many Iraqis were opposed to the Treaty, and it appeared the Treaty would not be signed. However, after threats by High Commissioner Percy Cox, the Treaty passed in the Constituent Assembly. Al-Askari subsequently resigned as Prime Minister due to his personal dissatisfaction.[3]: 57 [4]: 148–151

In November 1926, Faisal again appointed al-Askari (who at the time was acting as a Diplomatic Minister in London) Prime Minister of Iraq. Two main issues dominated his term in office: conscription and Shi'a discontent. Conscription was a controversial issue, with some believing it was needed to encourage a strong Iraq by creating a strong army.Sharifians—former Ottoman soldiers who had fought in the Arab revolt—saw conscription as a holy duty, and those in power also saw it as a way to create national unity and an Iraqi identity. On the other side, Iraqi Shi'a found it repugnant, and the various tribes who wished to be autonomous found it threatening. The British were not in favor of conscription, as they thought it could lead to issues in Iraq that would require their intervention, and they also wanted to keep the country weak to enable them to have tighter control of the country. Further complicating al-Askari's term was the growing Shi'a discontent in Iraq with massive protests occurring across the country in response to a book written by a Sunni official criticizing the Shi'a majority, as well as the promotion of the commanding officer of an army unit that opened fire on Shi'a demonstrators during a rally. Also at this time, the British wanted a new Anglo-Iraqi Treaty signed. Among the numerous powers the British retained in the new Treaty, the British would support Iraq's entry into the League of Nations in 1932—not in 1928 as previously promised—as long as it kept itself progressing in a manner consistent with British supervision. Al-Askari resigned as Prime Minister in December 1927 as a result of the lukewarm reception the Draft Treaty received among the Iraqi people and the growing discontent among the Shi'a majority.[3]: 61–63 [4]: 177–178

In addition to his two terms as Prime Minister, al-Askari also served as Minister for Foreign Affairs, as Diplomatic Minister in London, and as Minister of Defense on four separate occasions.[2]: 273–274 He was elected as the President of the Chamber of Deputies in November 1930 and in November 1931.[5][6]

Assassination and aftermath

During the 1936 military coup led by Bakr Sidqi against the government of Yasin al-Hashimi, al-Askari, who was serving as Minister of Defense, was sent to negotiate with Bakr Sidqi in an attempt to stop the violence, and to inform him of the new change in government, since Hashimi resigned and was replaced with Sidqi's ally Hikmat Sulayman. Sidqi was suspicious and ordered his men to intercept and kill al-Askari. His body was hastily buried along the roadside as Sidqi's supporters triumphantly took over Baghdad.[7] It is mentioned in some sources that Sidqi claimed to be a distant cousin of al-Askari.[8]

Al-Askari's assassination proved to be detrimental to Sidqi. Many of Sidqi's supporters in the army no longer supported the coup, as al-Askari was popular among the rank-and-file—many of whom had been recruited and trained under him. His death helped to undermine the legitimacy of Sidqi's government. The British, the Iraqis, and many of Sidqi's supporters were horrified by the act. The new government only lasted 10 months before Sidqi was assassinated in a plot by the Officers' Corps of the Iraqi army. After his assassination, his government was dissolved and Sulayman stepped down as Prime Minister. Al-Asakari's brother-in-law was not content with Sidqi's death, and sought revenge against those he found responsible for al-Askari's death. He claimed Sulayman and others were plotting to assassinate King Ghazi. The evidence was speculative and, in all likelihood, false, and yet they were found guilty and sentenced to death, later commuted to life in prison.[3]: 88–89, 98 [4]: 249–250

References

- Al-Askari, Kefah (1933). Al-Askari family: origin and branches. Baghdad. p. 12.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Al-Askari, Jafar Pasha (2003). Facey, William; Ṣafwat, Najdat Fatḥī (eds.). A Soldier's Story: From Ottoman Rule to Independent Iraq: the Memoirs of Jafar Pasha Al-Askari. Arabian Pub. ISBN 9780954479206. OL 8479542M.

- Tripp, Charles (2002). A History of Iraq. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521702478. OL 18384194M.

- Longrigg, Stephen Hemsley (1956). Iraq, 1900 to 1950: A Political, Social, and Economic History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780598936608.

- Report by His Britannic Majesty's Government to the Council of the League of Nations on the Administration of Iraq (Report). Colonial Office. 1930. p. 17.

- Report by His Britannic Majesty's Government to the Council of the League of Nations on the Administration of Iraq (Report). Colonial Office. 1931. p. 10.

- "Further Correspondence Parts XXXVIII & XXXIX" (1936). Foreign Office: Confidential Print, ID: FO 406/74. Kew: The National Archives of the United Kingdom.

- Basri, Mir (2004). أعلام السياسة في العراق الحديث [Political Figures in Modern Iraq] (in Arabic). Vol. 2. London: Dar al-Hikma. p. 268. ISBN 9781904923084.