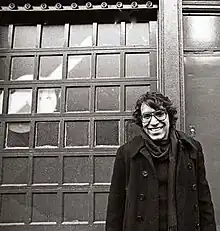

Jack Agüeros

Jack Agüeros (September 2, 1934 – May 4, 2014) was an American community activist, poet, writer, and translator, and the former director of El Museo del Barrio.

Jack Agüeros | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 2, 1934 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | May 4, 2014 (aged 79) New York City, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | American |

| Genre | Short stories, plays, and poetry |

| Children | 3 |

| Website | |

| jackagueros | |

Early life

Jack Agüeros was born September 2, 1934, in New York City, and grew up in East Harlem. His parents, Carmen Diaz and Joaquin Agüeros, had immigrated separately from Puerto Rico to New York. Carmen worked for many years as a seamstress, while Joaquin was in the merchant marine and also worked in restaurants and factories.[1] Agüeros attended Public School 72 (now the Julia de Burgos Cultural Center) and then Benjamin Franklin High School, East Harlem's first public high school, from which he graduated in June 1952.[2]

After serving for four years in the United States Air Force as a guided missile instructor, he attended Brooklyn College on the G.I. Bill, intending to become an engineer. Inspired by Bernard Grebanier, a charismatic professor of English, and his lectures on Shakespeare, Agüeros began writing plays and poems, and instead graduated with a B.A. in English literature and a minor in speech and theatre.

Activism

During the 1960s, Agüeros worked with a variety of community groups in New York. Starting out at the Henry Street Settlement, he moved on to the Office of Economic Opportunity, a federal agency created by President Lyndon Johnson to fight the War on Poverty, before becoming the deputy director of the Puerto Rican Community Development Project (PRCDP),[3] the nation's first Puerto Rican anti-poverty organization.[4]

After resigning from the PRCDP in early 1968,[5] Agüeros was appointed in April as deputy commissioner of New York City's Community Development Agency (CDA), created by Mayor John Lindsay.[6][7] As deputy commissioner of the CDA, he was the highest ranking Puerto Rican in the City's administration, and in 1968 staged a five-day hunger strike to protest the lack of Puerto Ricans in City government.[8]

Agüeros went on to be a member of the first cohort of National Urban Fellows, working as an advisor to the mayor of Cleveland and earning a M.A. in Urban Studies from Occidental College. He returned to New York and in 1970, became director of Mobilization For Youth, an organization located in the Lower East Side that provided job training and placement, social services, and special educational programming.[9]

Early writing

Jack Agüeros wrote his first poems and plays while still a student at Brooklyn College, receiving his first literary awards there. He continued to write while working as a community activist in the 1960s and early 1970s. Among the highlights from this period are the script for "They Can't Even Read Spanish," a half-hour play about Puerto Rican life in New York that aired on WNBC TV Channel 4 on Saturday, May 8, 1971.[10] The script is now preserved at the Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños[11] at Hunter College.

Agüeros also wrote a script for Sesame Street, "No Matter What Your Language".[12] The song by that name first appeared on the show in its third season (1971–1972). In the song, which has since been featured in a number of episodes, a Spanish speaker teaches an English speaker that, if they take the time, anyone can learn a new language. Agüeros was a member of the National Board for Bilingual Programming for Sesame Street, which received a portion of the show's budget to produce Spanish-language content, and was quoted at the time as being dissatisfied with the show's attempts at bilingualism.[13]

Agüeros's essay "Halfway to Dick and Jane", about his childhood in East Harlem, was included in The Immigrant Experience: The Anguish of Becoming American, a collection published in 1971 by the Dial Press that also featured contributions from Czesław Miłosz and Mario Puzo. In his New York Times review of The Immigrant Experience, Gay Talese praised Agüeros's contribution, writing "In this book is the first published work of Jack Agueros [sic], impressively describing Puerto Rican homelife in East Harlem."[14]

Agüeros maintained an active interest in theatre, reviewing several plays for the Village Voice.[15] (He has also written for El Diario-La Prensa, Soho News, and New York Newsday.)

Two of Agüeros's poems were included in one of the first anthologies of Puerto Rican literature, Borinquen, edited by Maria Teresa Babin and Stan Steiner, which was published by Knopf in December 1974. The two poems, "Canción del Tecato" and "El Apatético", are both in Spanish and appear in the section "Where am I at? The Youth," which also includes Pedro Pietri's well-known poem "Puerto Rican Obituary". Both poems had originally been published in a literary journal, The Rican (based in Chicago, Illinois) in 1971, and both were later included in Agüeros's first book, Correspondence Between the Stonehaulers.

Agüeros also published two children's stories in Nuestro, the first national Latino magazine, which was launched in 1977. The first, "The Magic Maraca", appeared in English and in Spanish in the December 1977 issue and was illustrated by Agüeros's one-time neighbour and friend, the artist Robert Zakanitch. The second, "Cheo Y Los Reyes Magos" ("Cheo and the Three Kings"), written in English, was included in the December 1978 issue. His children's story written around the same time, Kari & the Ice Cream Cone, was later turned into a play co-written with David Smith, and produced at Monroe Community College Theatre in Rochester, NY, and at Eastern Connecticut State University Theatre, Willimantic, CT, in 1988 and 1994 respectively.

Cayman Gallery and El Museo Del Barrio

On June 10, 1975, the Friends of Puerto Rico, a non-profit organization founded and incorporated in 1956, opened the Cayman Gallery in a SoHo loft at 381 West Broadway, with Jack Agüeros as its first director.[16] The Cayman Gallery was one of the first galleries dedicated to Puerto Rican and Latin American art in New York City.[17]

In July 1977, Agüeros was appointed director of El Museo del Barrio by the Museo's Board of Trustees. That fall, he negotiated with Boys Harbor, a non-profit youth services agency, to relocate El Museo from its home on Third Avenue to its present location: the main floor of the Heckscher Building, a multi-tenant, city-owned property at 1230 Fifth Avenue, between 104th and 105th Streets.[18] In January 1978, Agüeros began El Museo's tradition of organizing a Three Kings Day Parade to celebrate the Epiphany. The Parade, held annually on January 6, includes live animals (including camels), school groups, and props and costumes, such as paper-mache figures of the Three Kings, made by artists.

During his tenure, Agüeros implemented a series of capital improvements and gallery expansions, and helped build El Museo's permanent collection. In 1979, he co-founded the annual Museum Mile Festival on Fifth Avenue with ten major institutions, including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Museum of the City of New York, and The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. He also articulated the evolution of El Museo to an institution with a pan-Latin American mission, telling an interviewer in 1978: "Our focus is no longer limited to Puerto Ricans. We are too culturally rich to force ourselves into ghettoes of narrow nationalism. El Museo now wants to embody the culture of all of Latin America. New York is the fourth or fifth largest Spanish speaking city in the world, with people from every Spanish speaking country, and El Museo must reflect everything that is Latino. We must look upon Latin America as our Indian ancestors did. They did not see artificial boundaries dividing nations. They saw an open world where they were free to travel from one place to another, pursuing their livelihood and mixing their culture."[19]

Agüeros served as director of El Museo until March 14, 1986.[18][20]

Later writing

After leaving the Museo, Agüeros's poems and short stories began to appear more regularly in literary magazines. For example, his poem "Sonnet After Columbus II" appeared in The Portable Lower East Side (Volume Six, Number One) in 1989 and he was a regular contributor to Hanging Loose, a magazine published three times a year by Hanging Loose Press. Two of his sonnets, "For Maddog" and "For Willie Classen", appeared in Hanging Loose 55, while "Sonnet For The Bicycle Rider's Leg", "Sonnet: The History Of Puerto Rico", and "Sonnet For Alejandro Roman, Remarkable Rider" all appeared in issue 64. The poems for Maddog and for Willie Classen are typical of Agüeros's use of a classical form to pay tribute to unusual poetic subjects: in the case of Maddog, a 19-year-old with (already) a long criminal record, and in the case of Classen, a boxer who died a few days after a fight at Madison Square Garden in November 1979.[21]

His poems also occasionally appeared in national magazines: for example, "Sonnet on the Location of Hell" was published in the April 1996 issue of the Progressive.

In 1991, Agüeros's first collection of poems, Correspondence Between Stonehaulers, was published by Hanging Loose Press. This was followed by Sonnets from the Puerto Rican (a play on Elizabeth Barrett Browning's famous Sonnets from the Portuguese) and Lord, Is This a Psalm?, which were also published by Hanging Loose in 1996 and 2002 respectively.

In 1996, Curbstone Press published Agüeros's Song of the Simple Truth: The Complete Poems of Julia de Burgos, the first book to collect all of the poems by the woman widely considered to be Puerto Rico's greatest poet and to present them in both Spanish and English. In his introduction to the book, Agüeros recounts seeing de Burgos twice on the streets of East Harlem in the 1950s and having a hard time believing that she was Puerto Rico's most famous poet, as one of his friends told him. He then mostly forgot about her until years later, as an adjunct professor at Touro College teaching English as a second language and public speaking, "[o]ne day I asked if they [his students, mostly Puerto Rican women] had ever heard of Julia de Burgos and to my surprise nearly every student had. Moreover, they repeated the 'Puerto Rico's greatest poet' line. I decided to find some poems by Julia de Burgos and translate them into English for my students to recite. Ever since I have been in her custody."[22]

Dominoes and Other Stories from the Puerto Rican, a collection of short stories, was published by Curbstone Press in 1993. Later short stories appeared individually, including "i always wanted to be an old man" in Hanging Loose 72 (Hanging Loose Press) in 1998 and "He is Shorter...A Story" in Prosodia (published by the New College of California, San Francisco) in 1999.

An autobiographical essay on Agüeros's love of bread, "Beyond the Crust", appeared in Daily Fare: Essays from the Multicultural Experience, an anthology that appeared in 1993. "Johnny United", a story centered on a stickball game in East Harlem, was included in Growing Up Puerto Rican, another anthology published in 1997 that also featured contributions from Abraham Rodriguez, Piri Thomas, Edwin Torres, and Ed Vega among others.

In parallel, Agüeros wrote plays, several of which ran off Broadway. Awoke One was produced at the Ensemble Studio Theatre in 1992; The Sea of Chairs was produced by the Medicine Show Theatre Ensemble in 1993; and Love Thy Neighbor was produced at HERE Theatre in 1994. Dream Star Café ran at Theater for the New City from January 31 to February 24, 2002. He also translated plays; for example, his English translation of Alberto Adellach's Sabina and Lucrecia was performed by the Puerto Rican Traveling Theatre in spring 1991.[23]

Awards and legacy

In 1973, Agüeros won a Council on Interracial Books for Children (CIBC) literary award in what was the CIBC's fifth annual contest. Founded in 1965, one of the CIBC's goals was to promote a literature for children that better reflects the realities of a multicultural society.[24]

Agüeros's play The News from Puerto Rico won the McDonald's Latino Dramatist Competition in 1989.

In April 2012, Agüeros was the recipient of the Asan World Prize for Poetry.[25]

In summer 2012, Agüeros's papers were donated to Columbia University, where they are housed in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library.[26][27]

Personal life and death

Agüeros married three times and had three children and five grandchildren.

Agüeros was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease in December 2004,[28] and died from related complications at his home in Manhattan on May 4, 2014, at the age of 79.[29] His brain was donated to the Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer's Disease and the Aging Brain at Columbia University Medical Center.

Publications

Short stories

- Dominoes and Other Stories from the Puerto Rican (Curbstone Press, 1993)

Poems

- Correspondence Between Stonehaulers (Hanging Loose Press, 1991)

- Sonnets from the Puerto Rican (Hanging Loose Press, 1996)

- Lord, Is This a Psalm? (Hanging Loose Press, 2002)

Translations

- Song of the Simple Truth: The Complete Poems of Julia de Burgos (Curbstone Press, 1996)

- Come, Come-My Boiling Blood: The Complete Poems of José Martí (unfinished and unpublished)

Contributions to anthologies

- Borinquen: An Anthology of Puerto Rican Literature, edited by Maria Teresa Babin and Stan Steiner (Knopf, 1974)

- The Immigrant Experience: The Anguish of Becoming American, edited by Thomas Wheeler (Dial Press, 1971)

- Daily Fare: Essays from the Multicultural Experience, edited by Kathleen Aguero (University of Georgia Press, 1992)

- Men of Our Time: An Anthology of Male Poetry in Contemporary America, edited by Fred Moramarco and Al Zolynas (University of Georgia Press, 1992)

- Currents from the Dancing River: Contemporary Latino Writing, edited by Ray González (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1994)

- Boricuas: Influential Puerto Rican Writings, edited by Roberto Santiago (Ballantine Books, 1995)

- Growing Up Puerto Rican, edited by Joy L. De Jesús (William Morrow and Company, 1997)

- Hispanic New York: A Sourcebook, edited by Claudio Iván Remeseira (Columbia University Press, 2010)

- Sunken Garden Poetry, 1992-2011, edited by Brad Davis (Wesleyan University Press, 2012)

Plays

- Dreamstar Café

- The Sea of Chairs

- The News from Puerto Rico

- No More Flat World

- House Warmer

- Awoke One

- They Can't Even Read Spanish

- The New York Cycle

- Blue Rings

- Dio

- Men More

- Bueno Pepo

- In Sight

- Alcatraz and Jaguarox

- Kari and the Ice-Cream Cone

See also

References

- Espada, Martín. "Jack Agüeros," "Jack Agueros". Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved August 31, 2012.

- "Benjamin Franklin High School (former) - Place Matters". www.placematters.net. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- Kihss, Peter (July 28, 1967). "Puerto Ricans Lay Inaction to Mayor; Puerto Ricans Accuse the Mayor Of Inaction on Their Proposals." The New York Times.

- Lee, Sonia and Diaz, Ande. "'I Was the One Percenter': Manny Diaz and the Beginnings of a Black-Puerto Rican Coalition." Journal of American Ethnic History, Vol. 26, No. 3 (Spring 2007).

- Kihss, Peter (January 25, 1968). "15 Top Officers Quit Puerto Rican Agency Here." The New York Times.

- (1968-04-22). "Agueros Made Aide of Poverty Agency." The New York Times.

- NYC Department of Youth & Community Development History, "DYCD - History". Archived from the original on September 7, 2012. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- Bigart, Homer (June 29, 1968). "High Poverty Aide Starts Fast After Dismissal; Vows to Stay in Office Until Demands Are Met -- Failed to File Tax Returns." New York Times.

- "Mobilization for Youth records, 1958-1970". www.columbia.edu. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- Berg, Beatrice (April 25, 1971). "This Bodega Sells Insight." The New York Times.

- "Personal Papers | Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños". Archived from the original on November 17, 2014. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- Interview with Carmen Dolores Hernández, Puerto Rican Voices in English: Interviews with Writers (Praeger, 1997)

- UPI (1971-04-26). "Dissension on 'Sesame Street'." Palm Beach Post

- Talese, Gay (August 29, 1971). "The Immigrant Experience; The Anguish of Becoming American. Edited by Thomas C. Wheeler. 212 pp. New York: The Dial Press. $6.95." The New York Times.

- Agüeros, Jack. "A moral Don Juan" (January 4, 1973), "Oedipus in the ghetto? Never!" (1973-02-22), "In a very Ghetto way" (1973-04-19), "The taste of things Latin" (1973-07-05). Village Voice.

- "1970's | Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños". Archived from the original on September 9, 2011. Retrieved October 27, 2012.

- "Boricua Culture". Archived from the original on October 10, 2007. Retrieved October 27, 2012.

- "EL MUSeo's HISTORY | el Museo del Barrio New York". Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2012.

- Carlos Ortíz (1978-04). "The Arts: Museo de la Gente." Nuestro.

- "EL MUSeo's HISTORY | el Museo del Barrio New York". Archived from the original on April 10, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2012.

- "Classen's death changed boxing in New York". ESPN.com. March 15, 2012. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- Agüeros, Jack. Song of the Simple Truth: The Complete Poems of Julia de Burgos (Curbstone Press, 1996)

- Bruckner, D. J. R. (1991-04-14). "The Games of Women Trapped in Madness." The New York Times

- Banfield, Beryle (Spring 1998). "Commitment to Change: The Council on Interracial Books for Children and the World of Children's Books." African American Review, Vol. 31, No. 1.

- Unnithan, Sangeetha (2012-05-05). "Blurring boundaries, their poems lash out at injustice." The Hindu

- Yee, Vivian (2012-08-30). "Papers of a Puerto Rican Poet Will Find a Home at Columbia." The New York Times

- "New York Stories". Archived from the original on November 16, 2012. Retrieved October 27, 2012.

- González, David (2008-03-20). "A Puerto Rican Poet's Last Fight With Alzheimer's." The New York Times

- González, David (2014-05-06). "Jack Agüeros, 79, a Champion of El Barrio, Dies." The New York Times

External links

- Author website

- Biography at poets.org

- A biographical and critical assessment by Martín Espada

- Jack Agüeros Papers, 1914-2012 at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University, New York, NY