Jacob Muschong

Jacob Muschong (Hungarian: Muschong Jakab, Romanian: Iacob Muschong, born 1868, Nagykikinda, Austria-Hungary - died 13 December 1923, Lugoj, Romania) was a Banat German industrialist, business magnate, philanthropist and investor who made a fortune producing bricks.[1] He is also known as the Brick King. He revived the Spa of Busiasch.

Jacob Muschong | |

|---|---|

| Born | Jakob Muschong 1868 |

| Died | 13 December 1923 |

| Nationality | Banat Swabian |

| Other names | Jakab Muschong "the Brick King" |

| Citizenship | Hungarian Romanian |

| Occupation(s) | Industrialist Investor |

| Known for | Reviving Busiasch |

| Board member of | CEO Dampfziegelwerke AG (Stream Brick Factory) CEO Közönséges tömörfaltéglákat árusító részvénytársaság (Ordinary Solid Wallbrick Selling plc) CEO Hatzfelder Dampfziegelei AG |

| Spouse | Margaret Bohn |

| Children | Borbála Margit Jakab Jr |

Life

Early years

He was born in Nagykikinda (Serbian: Velika Kikinda, now Kikinda, Serbia), a town in the Banat, in a Banat Swabian family with a long tradition in the production of bricks, however he had Banat French origin.[1] His surname was written as Mougeon before it got Germanized.[2] His grandparents and great-grandparents produced bricks in workshops located at the edge of Lugoj.[3]

Dampfziegelwerke AG

At the age of 20 years he married Margaret Bohn the daughter of a famous German industrialist specialized in the production of tiles and bricks that built the brick factory at Zsombolya (now Jimbolia, Romania) and Gyertyámos (Cărpiniş) and had other several factories in Europe.[3]

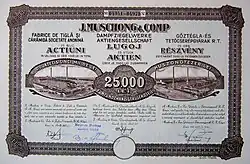

At the age of 20, Muschong and his wife founded the M. Bohn & Comp. which in 1888 built a brick factory in Lugoj. After several years he built a new plant in Lugoj and bought several factories from his competitors. In 1908 the company changed its name to J. Muschong & Comp.[3] Muschong brick and tile products were of high quality and were sold throughout the Austro-Hungarian Empire and then in Greater Romania. Muschong built more factories in Banat but he also built one at the outskirts of Budapest. In 1910 his company had 357 employees which made it the 23rd biggest employer in the Banat and the biggest in Lugoj.[4]

Bad Busiasch

He was also the founder of the Buziaş Spa (German: Bad Busiasch, Hungarian: Buziásfürdő).[3] He bought the bath and the 100 ha forest around it in 1906 from the family of the Hungarian tire manufacturer, Ernő Schottola. He built a bottling hall to produce bottled mineral water under the names Phönix[5] and Muschong.[6] He also built a carbon acid factory in 1907 for 2 million krones. The main export market for the mineral waters was the Balkan region. The plant had 700 m^2 area where the 700 HP steam engine and 60 HP electric engines provided the driving force. The plant had 36 employees.[7]

He carried out probing drills, which were successful: the water came from 103 meters deep and it became medically proven that the water was good for gout or gastric lavage.[8] He also laid the beautiful spa gardens with valuable plants, built a 500-meter-long covered walkway, 22 villas for spa guests, a zoo and sports fields.[9] He also raised a hotel in 1922-1923 which he named Muschong Hotel (now Felix Hotel) after himself.[10] In the same year he built a 2.9 km long railway with a normal gauge (1435 mm) between Buziaş railway station and the spa. According to the 1958 timetable, the journey took 7 minutes between the two stations. (On 10 October 1973 the railway line was dismantled.)[11]

Until 1948 the spa, the hotels and the bottling plant stayed in the Muschong family's ownership. Then it was nationalized.[12]

Budapest

According to the Cégfelszámoló (Company Directory) he was named as liquidator of the Egyesült magyar kénsavgyárak értékesítő szövetkezete (United Sulfuric Acid Manufacturers Cooperative, est. 1909, 11 Ipar utca, District IX, Budapest), shareholder of Kőbányai Gőztéglagyár (Steam Brick Factory of Kőbánya, est. 1876, 1 Erzsébet-körút, District VII, Budapest) and shareholder of the Közönséges tömörfaltéglákat árusító részvénytársaság (Ordinary Solid Wallbrick Selling plc, est. 1900, 27 Andrássy út, District VI).[13]

One of the most emblematic buildings of Lugoj is the Timiș Hotel which was built in 1926 as the Muschong Palace and was owned by Jakob Muschong.

Later years

In 1913 he worked as the CEO of Ziegel- und Kalkbrennerei AG in Budapest while his son, Jakab Muschong Jr was the manager of Bad Busiasch, co-leader of the Ziegel- und Kalkbrennerei AG and Hatzfelder Dampfziegelei AG, Zsombolya.[14]

After the Great Union of 1918 the Romanian authorities began the persecution of Jacob Muschong, considering that he opposes Romanian capital development.[3] He is teased and persecuted by a broad campaign of denigration by the media. Many financial controls from the authorities followed which discovered accounting irregularities alleged in the statements of income, considering the amounts invested by Muschong as profit and forcing him to pay tax on them.

Death

Soon after, Muschong died of a heart attack, on 13 December 1923 at his residence in Lugoj.[3]

After his death no one in the family could raise to the level of driving experience and ability that Jacob had. His wealth re-evaluated in today's money would probably amounts to over three billion dollars.[15] All his factories were nationalized by the communists in 1948 and largely demolished. Instead of his largest brick factory located on Timişorii street in Lugoj the communists built the Tiles and Sanitary Equipment Factory Mondial which was later privatized in 1996 to German investors and still exists today.[16]

Personal life

He was married to Margaret Bohn and had two daughters, Margit and Borbála and a son, Jakab. According to the Cégfelszámoló (Company Directory) his son, Jakab Muschong Jr. had a grenade patron company in 6203 Külső Bécsi út, Budapest, District III.[13]

Literature

- Ioan Sebastian Jucu : Selective issues on BUZIAŞ touristic resort of Romania between tourism economies and post-communist dereliction[17]

References

- József Kádár - Az óbudai Viktória

- László Palásti - Franciák és a francia nyelv a Bánátban a XVIII. és a XIX. században

- "Jacob Muschong, cel mai bogat lugojean din toate timpurile" (in Romanian). hotnews.ro. 2005-08-12. Retrieved 2009-09-10.

- Közép-Európai Közlemények - A történelemtudomány, a regionális tudomány, a földrajztudomány, és a gazdálkodás- és szervezéstudományok művelőinek folyóirata - VIII. year 2. Vol., 2015/2. No. 29

- Nyugati Jelen - Sipos - Újabb tulajdonosváltás előtt Buziásfürdő?

- Europeana Collections - Buziási "Phönix" forrás savanyúvize | Muschong Jakab; Grafikai Intézet Rt.

- Samu Borovszky - Magyarország vármegyéi és városai - MAGYARORSZÁG MONOGRÁFIÁJA - Temes vármegye

- infotourism.info - Temes megye – Buziásfürdő

- Balthasar Waitz - Grünes Licht für die Sanierung des Kurparks - February 8, 2017

- Heti Újszó - Graur János – Buziásfürdő Legenda és valóság az emlékek tükrében

- - Buziásfürdő

- Ribana Linc, Angela Ioana MARUŞCA - Spas at the west of the country

- Cégmutató Budapest bejegyzett működő cégeiről 1921. (Budapest)

- Compass 1913, I. Band - Seite 1850

- "Imperiul Muschong naste mostenitori" (in Romanian). hotnews.ro. 2006-04-15. Retrieved 2009-09-10.

- Dr Árpád Jancsó - Bányászati-kohászati kirándulásvezet

- http://gtg.webhost.uoradea.ro/PDF/GTG-2-2016/203_Jucu.pdf