Jacob Schaefer (composer)

Jacob Schaefer (Yiddish: יעקב שײפער, 1888–1936) was a Russian-born Jewish American composer, political activist and choir director whose career ran from the 1910s to the 1930s.[1][2] A committed Communist for the last two decades of his life, he founded and operated a number of workers' orchestras and choirs in Chicago and New York, including most famously the Freiheit Gezang Farein. He composed a number of cantatas, oratorios and song arrangements which were performed by the ensembles he directed, as well as by their affiliated performing groups around the United States.[3][4]

Jacob Schaefer | |

|---|---|

יעקב שײפער | |

| |

| Born | October 13, 1888 |

| Died | December 1, 1936 (aged 48) The Bronx, New York, United States |

| Occupation(s) | Composer, carpenter, choral director |

Biography

Early life

Schaefer was born in Kremenets, Volhynian Governorate, Russian Empire (now located in Ternopil Oblast, Ukraine) on October 13, 1888.[5][6][7] Jacob was born into a Jewish family of carpenters; his father, Moishe-Dovid, was a follower of Hasidic Judaism who knew many traditional songs and niguns, and his mother was named Hania-Chava.[3][5][8] (His father spelled the family name Soifer (סופר), which Jacob occasionally did as well even after emigrating.[5]) Jacob had a traditional Jewish education, studying in a Cheder.[2][5] Being immersed in the local Hasidic music world, Jacob became interested in famous cantors and in particular the idea of piano accompaniment to singing, but had no outlet for his newfound interest.[5] When he was 10 a new cantor Yankl Drohobitch arrived in town; Jacob's mother convinced him to take on Jacob as a student and assistant, and he soon became the soloist in Drohobitch's choir.[5][6][2] Jacob learned the basics of music notation, composition and vocal technique from him.[5] When Drohobitch left to become rabbi in a synagogue in Brody, Austria-Hungary, Jacob followed him as his assistant, against his parents' wishes who had been told he was only going briefly to perform at a wedding.[5][2] In addition, Drohobitch did not allow him to leave, telling him that he would not be able to cross the border back to Russia on his own. Nonetheless, during the three years he was living there, Jacob received an informal education in history, math and German from fellow boys who were enrolled in school there.[5][2] It was there that he was exposed to socialist politics for the first time.[5] After three years, when it came out that Jacob had been brought to Brody under false pretenses and forced to stay by Drohobitch, he was allowed to return home to Kremenetz.[5] When he returned he was sixteen years old and felt out of place; he rejected an offer to become a butcher's apprentice, preferring to work in his father's carpentry workshop and study music, Russian and politics on his own time.[2][5]

_Great_Synagogue.jpg.webp)

In around 1905 he tried to found a choir in Krememets, but did not have much success.[2] In 1908 he joined the General Jewish Labour Bund.[5] He entered into a relationship with a local girl Sonia Efrat against the wishes of her family, who were from a higher social class; she encouraged him to pursue his musical interests.[2][5] Finding Kremenets an unsatisfactory environment for that, and not being able to get away from the hostility of her family, they traveled to Bremen and from there emigrated to the United States in 1910.[6][2][5] After a brief stay in Baltimore, they settled in Chicago, where Jacob started working as a carpenter once again.[9] He met a man named Kerish in the carpentry workshop who shared his interest in music and who helped him get his first music gigs.[9] Jacob soon started working as a substitute singer and part time synagogue choir director, and continued to study music theory under a local musician named Samuel Epstein.[6][2][9] It was through his new higher-paying music jobs that in 1911 he was able to purchase his own piano for the first time in his life.[9]

Music career

In his first few years in Chicago he made a few unsuccessful attempts to found secular choirs.[2] One of them in late 1911 was funded by the Hebrew Institute, which at that time was trying to attract a younger membership.[9] However, the Institute reacted poorly to the workers' songs the choir was rehearsing and withdrew their support.[9] A later workers' choir he conducted, which was affiliated with Poale Zion, likewise fell apart before long.[9] Nonetheless, he became increasingly popular during this time as a piano accompanist, emerging composer, and synagogue choir director who could be relied upon to give good results.[9]

It was in 1914 that Schaefer decided to leave carpentry behind and devote himself completely to music.[6][10] During the summer of 1914 there were extensive discussions among Jewish socialists in Chicago about the idea of founding a politically active singing society (Yiddish: סאָציאַליסטישן געזאַנג-פאַראײן sotsialistishn gezang-farayn).[10] Despite some misgivings, when the Arbeter Ring made its intentions known to found its own choir, the socialists did indeed found their singing society, inviting a long list of singers from various synagogue choirs.[10] Schaefer, as both a left-wing working man and a reliable conductor, was recruited to lead it.[10][11] That was how he ended up helping to found one of the first Jewish folk choirs in the United States.[2][12]

The financial backers of the singing society were initially nervous when he brought his own compositions for the group to sing; however, as his arrangements proved skillful and popular they soon began to support it.[10] He soon founded an affiliated mandolin orchestra, and dedicated himself to composing and arranging music for both of these ensembles.[2] It was in April 1915 that the singing society performed his first oratorio, Martirer blut (Martyr's blood), which was based on poems by the Belarusian socialist poet Avrom Lesin.[10][2] The concert was sold out, exceeding expectations.[10] It was followed in November of the same year by his next work, Beyn hashmoshes.[10] He stayed in Chicago during World War I.[7] His next project was to arrange 18 Yiddish folk songs, which the choir performed in February 1916 along with The Internationale, La Marseillaise and other staples of socialist gatherings.[10] After that, he entered into an ideological dispute with the choir's backers and did not compose any major works again until 1920.[10] The gap in composition during that time is also sometimes attributed to the unexpected death in January 1917 of his wife Sonia, who passed away during a minor operation.[10][2] He also heard about his own father's death later in the same year.[10]

Despite his family misfortunes, he continued to throw himself into his work. In December 1917 he met Moissaye Joseph Olgin who was visiting from New York to speak at a Bund event.[10] Olgin was very impressed by the singing association and would later lend his support to help Schaefer and others found similar singing groups in other cities.[10] After this time he started traveling between Chicago, New York City and New Jersey, conducting various different choirs, including the Harfe choir in New York and another in Paterson, New Jersey; when he was away his Chicago duties were taken over by H. Stern.[10][2] He also became a music teacher in Arbeter Ring schools and studied music theory under David Menes.[2] He returned to Chicago in 1919, where he founded a socialist symphony orchestra and resumed leadership of the singing society.[2][10] He brought his mother to Chicago in 1920, but she fell ill within six-month and died.[10]

By 1921 the society broke with the Socialist Party and aligned itself with the Communist Party; Schaefer followed Olgin's suggestion and renamed it the Freiheit Gezang Farein (Freedom singing society).[2][12] Schaefer himself joined the Communist Party at this time and his compositional themes began to be more closely linked to the October Revolution and the Soviet project.[12][2] His first project during this new era was based on a text by Alexander Blok, which Schaefer developed in 1922 into an oratorio named Di tsvelf (The twelve).[12] The singing society performed it in 1923; it was his most ambitious work yet, and would later become a major piece with his New York choir as well.[2] While still in Chicago, he also composed his next work Tsvey brider (Two brothers, based on a work by I. L. Peretz) which the singing society also performed.

During 1922–3 he lived with a couple named the Steinbergs; the wife, Lena (Leah) was a member of the choir and her husband Simon (Schlomo) was an administrative supporter although not a singer.[12] During that time he and Lena began a relationship and she left Simon, causing several years of very public disputes and legal cases between the two men.[12][13][14] That public dispute contributed to Schaefer leaving Chicago for New York in around 1924, although he continued to go back and forth to debut new works.

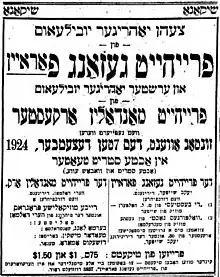

In New York, he was very impressed by the first concert in 1924 of a new choir which was supported by Olgin and was also named the Freiheit Gezang Farein. The composer Lazar Weiner founded it and was its director in its early years, although some sources state that Schaefer co-founded it.[12] Schaefer began to compose for it and eventually took on a leadership role as well.[12] Many members of the New York choir were garment workers.[15] Schaefer soon founded a companion mandolin orchestra, the Freiheit Mandolin Orchestra, as he had in Chicago. He also took leadership once again in the Paterson, N.J. and Brunswick choirs which had by now become Freiheit-affiliated singing societies as well.[16] During his first two years in New York Schaefer also studied music theory under Frank Patterson.[1] The choir soon grew quite large under his leadership and had several notable concerts of his works. It performed some of the pieces he had composed in Chicago such as Tsvey brider at the Mecca Temple in 1926 and Di tsvelf at Carnegie Hall in April 1927.[12][2]

In 1925 Schaefer helped found another organization, the Jewish Workers Music Alliance (Yiddish: דער ייִדיש-מוזיקאַלישער אַרבעטער-פאַרבאַנד) under the leadership of the International Workers Order, which helped coordinate and support the growing network of Freiheit singing societies.[16][17] The Alliance also published Schaefer's arrangements, partly to allow far-flung affiliate choirs to perform them, and also consulted with them about musical or organizational issues.[16] For a time in 1928 he returned to Chicago once again with Lena, who had obtained a divorce in Mexico and remarried to Schaefer in New Jersey, and took up leadership of his choirs and orchestras there once again.[16] However, he was arrested on the complaint of Simon Steinberg as the divorce paper from Mexico was not considered valid.[16] It was only after the New York and Chicago singing societies raised a large amount of money to pay off Steinberg that he finally dropped his complaint.[16] He and Lena returned to New York.[16] Another difficulty in 1929 was that Lazar Weiner, founder of the New York section who had still been sharing conducting duties with Schaefer, came into a dispute with the Communist Party after preparing a programme for the Socialist Party.[16] Weiner was expelled from the party and lost his leadership role in the Freiheit choir.[16]

In 1930 the choir debuted his new oratorio October at Carnegie Hall.[16][18] This "revolutionary oratorio" incorporated poems selected by Nathaniel Buchwald from the works of Itzik Feffer, Leib Kvitko, Peretz Markish, Morris Rosenfeld, and others.[19][2]

In 1932 Schaefer traveled to Kharkiv at the invitation of Soviet poet Itzik Feffer, where he premiered October there with the support of the Ukrainian Philharmonic and choirs from Kharkiv and Kyiv, and in 1933 went to Moscow to represent his New York choir at the International Congress of Proletarian Musicians.[2][1][20] There was even the suggestion of a Soviet tour by his New York choir, although it never happened in the end.[2] Upon his return to New York in May 1933 the choir gave another concert at Carnegie Hall; Schaefer also toured around Chicago, Detroit, Toledo, and various other places.[21] After 1933 Schaefer was also a member of a left-wing composer's organization called the Composers Collective which included Charles Seeger, Henry Cowell, Elie Siegmeister, Aaron Copland, and Marc Blitzstein.[22][23][24] The main function of the group, which was a spinoff of the Communist-affiliated Degeyter Club, was to compose new radical music for workers' choirs like the Freiheit singing society; Schaefer, as an experienced conductor, urged the other Collective members to simplify their music to make it more accessible and singable for working class singers.[25][26][27]

His final major work was A bunt mit a statshke (Strike and revolt). This work, which included dance choreography and folk song arrangements, sought to portray scenes in the lives of workers via music collected by Soviet musicologist Moisei Beregovsky.[28] It was only performed by the choir after his death in 1937, after Max Helfman had taken over for Schaefer, and again in 1938.[28][29]

Schaefer died of a heart attack at his home in the The Bronx on December 1, 1936.[8][1][6] His funeral was held at the Central Opera House on 67th St. and was attended by more than fifteen thousand people.[30] He was buried at the New Montefiore Cemetery in Suffolk County, New York.[30]

Legacy

After Schaefer's death the Freiheit singing society continued to perform his compositions. In December 1937 they also performed in a joint memorial event for Schaefer, George Gershwin, and Henry Kimball Hadley, funded by the Works Progress Administration.[31] And the following year a biography of Schaefer was published by the Jewish Workers Music Alliance. It was written by Israel Ber Bailin, a longtime friend of Schaefer's who had been involved in politics with him in Chicago and had long promised to write his biography.[5] Other books published by the Alliance came out in later decades, including a collection of Schaefer's compositions entitled Ich Her a Kol in 1952 and an illustrated memorial book to mark the twentieth anniversary of his death in 1962.[32][33]

Selected works

Oratorios

- Martirer blut (Martyr's blood, 1915)

- Beyn hashmoshes (1915)

- Kirkhn-glokn (1920, an opera-oratorio based on a poem by Avrom Reyzen[10])

- Di tsvelf (The twelve, composed 1922, performed 1927, based on a poem by Alexander Blok[2])

- Tsvey brider (Two brothers, performed in Chicago in 1923 and in New York in 1926, based on a work by I. L. Peretz[2])

- Moshiakh ben Yosef (performed 1925, text by B. Shteinman[3])

- Oktober (performed 1930, with text arranged from various poets by Nathaniel Buchwald)

- Kein eintsikn shpan (composed and performed 1931, text by Peretz Markish[16][3])

- Geviter (together with I. Greenshpan)

- Biro-Bidzhan (text by Peretz Markish)

- A bunt mit a statshke (Strike and revolt, performed posthumously in 1937)

Cantatas

- Trupn geyen[3]

- Shturem foygl (Adaptation of Maxim Gorky, translated to Yiddish by Moissaye Joseph Olgin[3])

Published scores

- Mit gezang tsum kamf – Songs for Voice and Piano (International Workers Order, 1932, compiled by Jacob Schaefer)[34]

- Gezang un kamf 2 (Yidisher muzikalisher-arbeter farband, 1934, by Jacob Schaefer)

- Gezang un kamf 3 (YMAF, 1935, by Jacob Schaefer)

- Gezang un kamf 4 (YMAF, 1936, by Jacob Schaefer)

- Gezang un kamf 5 (Yidisher muzik-farband, 1937, by Jacob Schaefer and Max Helfman)[35]

- "Ich Her a Kol": 22 Selected songs of Jacob Schaefer (YMF, 1952)[32]

References

- "OBITUARY. Jacob Schaefer". Musical Courier. Summy-Birchard Publishing Company. 114 (14): 20. December 12, 1936.

- Zylbercweig, Zalmen; Mestel, Jacob (1931). Leḳsiḳon fun Yidishn ṭeaṭer Vol 6 (in Yiddish). New York: Elisheva. pp. 5909–62.

- Schaeffer, Jacob (1952). Cefkin, Misha; Green, Ber; Korenman, Irving R.; Novick, P.; Rauch, Maurice; Rubin, Ruth; Shain, Mendy; Yukelson, R.; Suller, Chaim (eds.). Tsṿey un tsṿantsig geḳlibene lider. New York: Idishe muziḳ farband. pp. 4–13.

- Heskes, Irene (1994). Passport to Jewish music : its history, traditions, and culture. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 207. ISBN 0313280355.

- Bailin, Israel Ber (1938). "1". Yaaḳov Sheyfer zayn lebn un shafn (in Yiddish). New York: Idishin muziḳalishn arbeṭer-farband. pp. 9–32.

- "JACOB SCHAEFER, COMPOSER, DIES". Times Union. Brooklyn, New York. December 2, 1936. p. 12A.

- "Jacob Soifer discovered in U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918". Ancestry.com. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- "Jacob Schaefer discovered in New York, New York, U.S., Index to Death Certificates, 1862–1948". Ancestry.com. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- Bailin, Israel Ber (1938). "2". Yaaḳov Sheyfer zayn lebn un shafn (in Yiddish). New York: Idishin muziḳalishn arbeṭer-farband. pp. 33–42.

- Bailin, Israel Ber (1938). "3". Yaaḳov Sheyfer zayn lebn un shafn (in Yiddish). New York: Idishin muziḳalishn arbeṭer-farband. pp. 44–72.

- Bailin, Israel Ber (1955). Perzenlekhkayṭn in der geshikhṭe fun Idn in Ameriḳe (in Yiddish). New York: Iḳuf farlag. pp. 12–3.

- Bailin, Israel Ber (1938). "4". Yaaḳov Sheyfer zayn lebn un shafn (in Yiddish). New York: Idishin muziḳalishn arbeṭer-farband. pp. 73–82.

- "SEEKS WRIT TO KEEP HIS WIFE FROM MARRYING". Chicago Tribune. Chicago. January 30, 1927. p. 16.

- "Asks Injunction to Prevent Wife from Marrying". Chicago Tribune. Chicago. January 31, 1927. p. 3. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- Jacobson, Marian (2006). "9. From Communism to Yiddishism: The Reinvention of the Jewish People's Philharmonic Chorus of New York City". In Ahlquist, Karen (ed.). Chorus and community. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. pp. 202–20. ISBN 9780252030376.

- Bailin, Israel Ber (1938). "5". Yaaḳov Sheyfer zayn lebn un shafn (in Yiddish). New York: Idishin muziḳalishn arbeṭer-farband. pp. 83–110.

- Biderman, Morris (2000). A life on the Jewish Left : an immigrant's experience. Toronto: Onward Pub. p. 45. ISBN 0968693709.

- "Freiheit Singing Society". Musical Courier. Summy-Birchard Publishing Company. 101 (26): 22. December 27, 1930.

- "ORATORIO "OCTOBER" SAT. NITE AT CARNEGIE". Daily Worker. Vol. 7, no. 303. December 19, 1930. Archived from the original on September 24, 2022. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- "Freiheit Chorus to Sing Oratorio by Own Conductor". Daily Worker. Vol. 10, no. 277. November 18, 1933. Archived from the original on September 24, 2022. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- "Freiheit Gezang Farein". Musical Courier. Summy-Birchard Publishing Company. 106 (19): 14–5. May 13, 1933.

- Denning, Michael (1998). The cultural front : the laboring of American culture in the Twentieth Century (Paperback ed.). London: Verso. p. 66. ISBN 1859841708.

- Copland, Aaron; Perlis, Vivian (1984). Copland. 1900 through 1942 (1st ed.). New York: St. Martin's /Marek. pp. 223–4. ISBN 0312169620.

- Wiley Hitchcock, H.; Sadie, Stanley, eds. (1986). The New Grove dictionary of American music, Volume 1 (A-D). New York, NY: Macmillan. p. 479. ISBN 0943818362.

- Denning, Michael (1998). The cultural front : the laboring of American culture in the Twentieth Century (Paperback ed.). London: Verso. p. 293. ISBN 1859841708.

- Pescatello, Ann M. (1992). Charles Seeger : a life in American music. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 111–2. ISBN 9780822937135.

- Buhle, Paul; Buhle, Mari Jo; Georgakas, Dan, eds. (1992). Encyclopedia of the American left (Illini books ed.). Urbana: University of Illinois Press. p. 158. ISBN 0252062507.

- K., R. (March 13, 1937). "Yiddish Folk Opera Sung". Musical Courier. Summy-Birchard Publishing Company. 115 (11): 25.

- "Max Helfman to Lead Freiheit Gezang Concert May 13". The Jewish Post. Paterson, N. J. May 5, 1938. p. 7.

- "JACOB SCHAEFER Music Leader Buried". Daily News. New york. December 7, 1936. p. 48.

- "TRIBUTES ARE PAID TO THREE COMPOSERS: Gershwin, Hadley and Schaefer Works Offered in Program of WPA Theatre of Music". The New York Times. New York. December 30, 1937. p. 13.

- "Tsṿey un tsṿantsig geḳlibene lider". Archive.org. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- "Yaʼaḳov Sheyfer ilusṭrirṭer zamlbukh tsu zayn finf un tsvantsiḳsṭn yortsayṭ". Yiddish Book Center. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- "Mit gezang tsum kamf". Internet Archive. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- "Gezang un kamf". Internet Archive. Retrieved September 25, 2022.