Jacques Desjardin

Jacques Desjardin (French pronunciation: [ʒak deʒaʁdɛ̃]) or Jacques Jardin or Jacques Desjardins; (9 February 1759 – 11 February 1807) enlisted in the French royal army as a young man and eventually became a sergeant. During the first years of the French Revolutionary Wars he enjoyed very rapid promotion to the rank of general officer in the army of the French First Republic. In May and June 1794 he emerged as co-commander of an army that tried three times to cross the Sambre at Grandreng, Erquelinnes and Gosselies and each time was thrown back by the Coalition. After that, he reverted to a division commander and saw more service in the north of France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. In the campaign of 1805, he led an infantry division under Marshal Pierre Augereau in Emperor Napoleon's Grande Armée and saw limited fighting. In 1806 he fought at Jena, Czarnowo and Gołymin. He was mortally wounded at the Battle of Eylau on 8 February 1807 and died three days later. His surname is one of the names inscribed under the Arc de Triomphe, on Column 16.

Jacques Desjardin | |

|---|---|

Bust of Desjardin sculpted by Antoine Laurent Dantan in the Galerie des Batailles at the Palace of Versailles | |

| Born | 9 February 1759 Angers, Maine-et-Loire, France |

| Died | 11 February 1807 (aged 48) Landsberg in Ostpreußen, now Poland |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Infantry |

| Years of service | |

| Rank | General of Division |

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards | Légion d'Honneur |

Revolution

Born on 9 February 1759 in Angers, France, Desjardin joined the French army on 8 December 1776 at the age of 17. Since his father worked as a humble valet, Desjardin's prospects of advancement in the Vivarais Infantry Regiment were poor. He became a corporal in 1781 and sergeant in 1789. He was granted leave to see his father in 1790 and immediately threw himself into the task of drilling his hometown National Guard unit. Coming to the attention of the revolutionary authorities, he was appointed adjutant general on 5 August 1791.[1]

After a reorganization, Desjardin became lieutenant colonel of the 2nd Battalion of the Maine-et-Loire National Guard. He led his troops in the Army of the North at the Battle of Jemappes on 6 November 1792. This action was followed by the Siege of Namur,[1] which lasted from early November until the Austrian surrender on 2 December. During the siege, Desjardin's battalion served in the Left Brigade of Louis-Auguste Juvénal des Ursins d'Harville's Reserve Division.[2] In the actions during Charles François Dumouriez's subsequent retreat from Belgium, Desjardin greatly distinguished himself. On 3 September 1793, he received promotion to general of brigade. When he became a general of division on 19 March 1794, he already had charge of three divisions.[1]

By 4 May 1794, Desjardin had command over a 31,736-strong army that consisted of François Muller's division, 14,075 men, Jacques Fromentin's division, 10,619 soldiers, and Éloi Laurent Despeaux's division, 7,042 troops. One month later, Desjardin's Right Wing of the Army of the North had grown to a strength of 37,147 men. There were 43 infantry battalions, nine cavalry regiments, and three artillery companies under his orders.[3] The French strategy for 1794 called for Desjardins to join the Right Wing with Louis Charbonnier's Army of the Ardennes to form a 60,000-man army to strike toward Mons. The objective was later changed to Charleroi. Unfortunately, the Army of the North's commander Jean-Charles Pichegru neglected one of the basic principles of warfare by failing to appoint a single overall commander for the army. Between 11 May and 3 June this force crossed the Sambre river three times and was driven back each time. In one overheard conversation between the co-commanders, Charbonnier sounded like a buffoon. He noted that the troops were starving and they needed to cross the river to feed them, to which Desjardin replied that the crossing must be arranged in a military fashion. Charbonnier answered, "Good, you work out the details. As for me, I'm in charge of eating vegetables and pumping oil". One political agent attached to the army remarked, "I did not see the shadow of treason, but the incapacity of the leaders was flagrant". Nevertheless, the oft-beaten army returned to the fray each time "as if it had come fresh from the barracks".[4]

In his critique of the French defeat in the Battle of Grandreng, historian Victor Dupuis noted that the 53,000 French soldiers should have made quick work of Franz Wenzel, Graf von Kaunitz-Rietberg's 22,000 Allies. Instead Desjardin with 35,000 poorly trained troops attacked Kaunitz's men in fortified positions without support from the French heavy cannons because of the poor condition of the roads. While the battle was going on, the uncooperative Charbonnier was to the east on a foraging expedition. As Guillaume Philibert Duhesme later wrote, "We were all children in the art of war".[5] For the next attempt, the army was to be guided by a council of Generals Desjardin, Charbonnier, Jean-Baptiste Kléber and Barthélemy Louis Joseph Schérer.[4]

The French army re-crossed the Sambre and on 21 May the opposing armies fought a drawn battle during which one of the Army of the Ardennes divisions remained completely inert because Charbonnier failed to approve its movements.[6] Two days later, the committee of generals authorized Kléber to take 15,000 troops on a raid to the north.[7] On 24 May in the Battle of Erquelinnes, Kaunitz launched a pre-dawn attack in five columns, catching Desjardin's troops completely by surprise and capturing hundreds of sleepy French soldiers. Total disaster was averted when Kléber heard cannon fire and countermarched, helping to slow the Allied pursuit.[8] Urged on by the political agents, the French generals decided to attempt a third advance.[9] With the better part of this force, Desjardin laid siege to Charleroi. On 3 June, a 28,000-man Austro-Dutch relief force under William V, Prince of Orange defeated him in the Battle of Gosselies, inflicting 2,000 casualties on the 27,000 French who were present and capturing one 12-pound cannon. For a loss of 424 killed and wounded, the allies drove the French south of the Sambre and broke the siege.[10] Charbonnier was sacked and Desjardin was given command of the army. However, Jean-Baptiste Jourdan's 45,000-strong Army of the Moselle arrived and on 8 June took over command from Desjardin. On 13 June the combined force became the Army of Sambre-et-Meuse.[11]

Desjardin participated in the siege of Le Quesnoy, which ended on 16 August 1794 with an Austrian surrender.[1][12] During the Siege of Luxembourg his division and two others replaced the original besieging corps. Desjardin's 8th Division counted 12,972 infantry, 682 cavalry, 205 gunners and 188 sappers. His 1st Brigade under Jean-Baptiste Rivet was made up of the 53rd and 87th Line and the 1st Battalion of the Sarthe Volunteers and the 5th Battalion of the Yonne. Nicolas Soult's 2nd Brigade included the 66th and 116th Line. The division's mounted contingent was the 7th Cavalry Regiment.[13] After the reduction of Luxembourg City, which lasted until June 1795, Desjardin remained in the Army of the North. During 1796 he became part of the occupation forces of the former Dutch Republic.[1] After the Rhine Campaign of 1796, Desjardin took command of the division of Jean Castelbert de Castelverd who was in disgrace.[14] In February 1797 he replaced Jacques MacDonald in command of the Army of Sambre-et-Meuse's Left Wing.[15] In October 1801 he was placed on inactive duty.[1]

Empire

On 28 February 1804, the soon-to-be Emperor Napoleon made Desjardin a member of the Légion d'Honneur and recalled him to military service at Brest. In recognition of his services, the emperor appointed him a Commander of the Légion d'Honneur on 14 June 1804.[1] In 1805, Desjardin was appointed to command a division in Marshal Augereau's VII Corps.[16]

Having a long march from Brest to the Danube at the start of the War of the Third Coalition, Augereau's corps missed the Ulm Campaign in October 1805. While the main army was headed for a showdown at the Battle of Austerlitz, the VII Corps operated against enemy troops in the Vorarlberg. The French tracked down Franz Jellacic's Austrian division on the upper reaches of the Iller River.[17] On 13 November 1805, Augereau, accompanied by Desjardin's 1st Division forced Jellacic to surrender in the Capitulation of Dornbirn. Three generals, 160 officers, and 3,895 rank and file laid down their arms and were permitted to march to Bohemia where they were not to undertake operations against France for one year. Seven colors became trophies of the French.[18]

At the beginning of the War of the Fourth Coalition, Desjardin still commanded the 1st Division of the VII Corps, a total of 8,242 soldiers and eight artillery pieces. Pierre Belon Lapisse's brigade consisted of the 4-battalion 16th Light Infantry Regiment. Jacques Lefranc's brigade comprised the 44th and 105th Line Infantry Regiments, three battalions each, and the 2nd Battalion of the 14th Line Infantry Regiment. The divisional artillery was made up of a half company each of foot and horse artillery and included two 12-pound guns, four 6-pound guns, and two 6-inch howitzers.[19]

At the Battle of Jena, Augereau's corps formed the left flank as Napoleon engaged the Prussian-Saxon army of Frederick Louis, Prince of Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen. Led by Lapisse's 16th Light, Desjardin led his division up the Schneke Pass against Hans Gottlob von Zeschwitz's Saxon Division posted on the Prussian right flank. They soon bore to the right to form a flank guard to Marshal Jean Lannes' main attack.[20] As the French attack pressed forward, the 1st Division captured the village of Isserstadt around 11:30 AM.[21]

When Ernst von Rüchel made his belated and futile attack after 1:00 PM, it was opposed by the artillery of Desjardin, as well as the guns of Marshals Nicolas Soult, Michel Ney, and Lannes.[22] Meanwhile, Augereau's main assault fell on Zeschwitz's Saxons and a supporting Prussian brigade under Karl Anton Andreas von Boguslawsky. While Étienne Heudelet de Bierre's 2nd Division hammered at the Saxons from the front,[23] part of Desjardin's division turned their left flank. By 3:00 PM, the Saxons were completely cut off from Hohenlohe's main army. Seeing an opportunity, Marshal Joachim Murat led Louis Klein's dragoons to take the Saxons in the rear while Jean-Joseph Ange d'Hautpoul's cuirassiers attacked their left flank.[24] Zeschwitz cut his way out of the trap at the head of 300 cavalrymen, but a total of 6,000 Saxons and Prussians were forced to surrender.[25]

In November, the corps of Lannes, Augereau, and Marshal Louis-Nicolas Davout thrust into Prussian Poland.[26] In late December, Napoleon launched an offensive against the Russian Empire armies that were gathering against him.[27] At the Battle of Czarnowo on 23 and 24 December, the French pressed their enemies back.[28] Also on the 24th, Augereau directed his two divisions to force a crossing of the Wkra River in the face of nine Russian infantry battalions and five cavalry squadrons under Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly. Heudelet's attack at Sochocin was repulsed by three battalions. Furious at this setback, he ordered a second attack which only resulted in more casualties. At Kołoząb, Desjardin ordered the 16th Light to line the west bank of the river to give covering fire while the grenadier company of the 14th Line stormed the incompletely demolished bridge. Securing a foothold, the grenadiers were rapidly reinforced and repelled counterattacks by Russian infantry and hussars. Aided by Lapisse's task force which crossed 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) downstream, Desjardin's men drove off the Russians and captured six cannons. Augereau lost 66 men killed and 452 wounded in these two actions.[29]

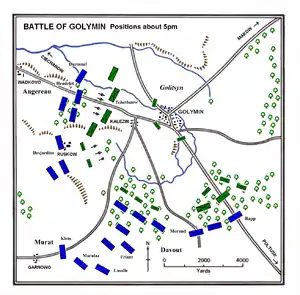

Two days later, Desjardin fought at the Battle of Gołymin.[30] In this action, Dmitry Golitsyn with 16,000 to 18,000 Russians held off 37,000 to 38,000 Frenchmen under Marshals Davout and Augereau. The large French numerical advantage was partly offset by the fact that Golitsyn had taken up an excellent defensive position. The Russians also employed 28 pieces of artillery, while the French could get no guns forward because of the poor condition of the roads.[31] After a cavalry clash, Desjardin's division was the first French infantry to reach the battlefield.[32] Heudelet's division marched on a different road and took position on Desjardin's left. Repeatedly attacked by cavalry, Heudelet was forced to keep his men in square and consequently could make little forward progress. Desjardin attacked with more verve, pressing back a Russian infantry regiment. Reinforced, the Russians pushed his troops back in turn. Rallying his men, Desjardin ordered a new advance but it was stopped by point-blank artillery fire. After Augereau's advance ended in a stalemate,[33] Davout's troops appeared on the scene. At first they were successful, but this attack eventually stalled and the Russians retreated that evening in good order.[34] Russian casualties are put at 775, but this may be too low. The French claimed that their losses were the same as their adversaries.[31]

On 7 and 8 February, the French and Russian-Prussian armies fought the costly Battle of Eylau. Soult's troops were involved in a hot fight with the Russian rear guard on the 7th. Augereau was ordered to help by moving against the enemy right flank, but his troops were not seriously engaged.[35] At 8:00 AM on the 8th, the VII Corps was brought into the battle line with its left flank at the Preußisch Eylau church. Desjardin's division was in the first line and Heudelet's was in the second. This move split Soult's IV Corps, placing the divisions of Claude Legrand and Jean François Leval to Augereau's left and Louis-Vincent-Joseph Le Blond de Saint-Hilaire's division to his right.[36] This day, Augereau was not in good health. He had asked Napoleon for sick leave the evening before, but the emperor talked him into staying on for one more day.[37]

Around 9:00 AM, Napoleon ordered Soult to attack on the left, but his two divisions were thrown back by the Russians after a terrific struggle.[38] Fearing that his enemies might crush his left flank, the emperor ordered Augereau and Saint-Hilaire to advance. They were instructed to bear slightly to the right in order to contact Davout's corps, which was beginning to arrive on the right flank. At 10:00 AM, when the troops were set in motion, a blinding snowstorm swept across the field.[39]

Augereau arranged his divisions so that the leading brigade's battalions were deployed in line and the trailing brigade's battalions formed in mobile squares. Historian David G. Chandler suggested that Augereau should have formed his men in battalion columns in the prevailing weather conditions. Saint-Hilaire's division managed to keep a true course, but the VII Corps soon lost its way, veering to the left. Not only did this create a dangerous gap on Augereau's right flank, but it sent his men marching blindly into range of a 70-gun grand battery in the center of the Russian line. When the Russian guns opened up, they began to mow down hundreds of Augereau's hapless infantry.[37]

The Russian commander Levin August, Count von Bennigsen, sent his reserves to counterattack the badly disordered French infantry. In the white-out conditions, Russian cavalry appeared out of nowhere and began to cut down the French foot soldiers. Survivors related that their muskets often misfired because of the wet snow. Massacred by artillery and assailed by infantry and cavalry, the VII Corps panicked and fled. As the snowstorm began to abate, Napoleon watched their mob-like flight to the rear. He ordered Murat to lead a massed cavalry charge, which put the Russians back on the defensive and gave Davout time to start pressing back the enemy's left flank. That evening, the acting VII Corps commander Jean Dominique Compans reported that only 700 men were with the colors from each of the divisions. He stated that 30 officers above the rank of chef de bataillon (major) were killed or wounded. Later, Augereau's official report noted that he lost 929 killed and 4,271 wounded, but did not give the number of missing.[40] One of Augereau's aides, lieutenant Marbot believed that only 3,000 men were unwounded out of the 15,000 present for duty on the morning of the 8th.[41] Soon after, Napoleon dissolved the VII Corps and sent the surviving units to fill out the other army corps.[42]

During the slaughter of his division, Desjardin fell gravely wounded. He was removed to the town of Landsberg (Gorowo Ilaweckie) where he died on 11 February 1807. The name DESJARDINS is inscribed on Column 16 of the Arc de Triomphe in honor of the fallen general.[1]

Notes

- Mullié, Jacques Jardin

- Smith, 32. Smith misspelled Harville as Marville.

- Smith, 70–71. The author misspelled Muller as Miller

- Phipps 2011, pp. 145–147.

- Dupuis 1907, pp. 141–144.

- Dupuis 1907, p. 165.

- Dupuis 1907, p. 167.

- Dupuis 1907, pp. 172–179.

- Dupuis 1907, p. 184.

- Smith 1998, p. 83.

- Phipps 2011, p. 150.

- Smith, 89

- Lefort (1905), 69–71

- Phipps 2011, p. 389.

- Phipps 2011, p. 410.

- Chandler Campaigns, 1103

- Chandler Campaigns, 402-403

- Smith, 214

- Chandler Jena, 37

- Chandler Jena, 54 map

- Chandler Jena, 60

- Petre Prussia, 142-143

- Petre Prussia, 143

- Petre Prussia, 144

- Petre Prussia, 145

- Chandler Campaigns, 514

- Petre Poland, 75

- Petre Poland, 79-82

- Petre Poland, 84-85

- Smith, 236

- Petre Poland, 114

- Petre Poland, 109

- Petre Poland, 110

- Petre Poland, 111-112

- Petre Poland, 165-166

- Petre Poland, 178

- Chandler Campaigns, 542

- Chandler Campaigns, 541

- Petre Poland, 180

- Petre Poland, 181-182

- Petre Poland, 184

- Petre Poland, 227

References

- Chandler, David G. (2005). Jena 1806: Napoleon Destroys Prussia. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-98612-4.

- Chandler, David G. (1966). The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York, N.Y.: Macmillan. OCLC 401930.

- Dupuis, Victor (1907). Les operations militaires sur la Sambre en 1794 (in French). Paris: Librarie Militaire R. Chapelot et Cie. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- Lefort, Alfred (1905). Publications de la Section Historique: De l'Institut G.-D. de Luxembourg (in French). Vol. 50. Luxembourg: Worré-Mertens. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- Mullié, Charles (1852). Biographie des célébrités militaires des armées de terre et de mer de 1789 a 1850 (in French). Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Petre, F. Loraine (1976) [1910]. Napoleon's Campaign in Poland 1806-1807. London: Lionel Leventhal Ltd.

- Petre, F. Loraine (1993) [1907]. Napoleon's Conquest of Prussia 1806. London: Lionel Leventhal Ltd. ISBN 1-85367-145-2.

- Phipps, Ramsay Weston (2011) [1929]. The Armies of the First French Republic: Volume II The Armées du Moselle, du Rhin, de Sambre-et-Meuse, de Rhin-et-Moselle. Vol. 2. USA: Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 978-1-908692-25-2.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.