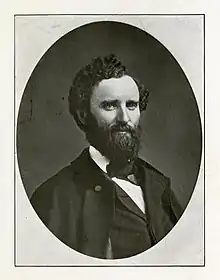

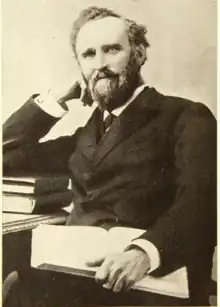

James B. Simmons

James B. Simmons (c. 1827 – December 17, 1905), was a minister and abolitionist during the Antebellum period. He served as a Baptist minister in Providence, Rhode Island; Indianapolis, Indiana; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and New York City.

James B. Simmons | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1827 |

| Died | December 17, 1905 (aged 77–78) |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Minister, missionary, and abolitionist |

| Known for | A founder of Hardin-Simmons University |

After the American Civil War, he was an American missionary who was Corresponding Secretary of the American Baptist Home Mission Society from 1867 to 1874. He was an early benefactor and trustee of Hardin–Simmons University in Texas, which is partially named for him.

Early life and education

He was born in North East, Dutchess County, New York in 1827.[1][2][lower-alpha 1] His father William Simmons was a thrifty farmer of Dutch extraction.[3] His mother Clarissa Roe, of Scotch descent, was thrown from a carriage and killed when James was not quite five months old.[4]

He had four older siblings:[2] Hervey Roe, Edward W. Julia and Amanda. His brother Edward, eleven years older than Simmons, was a teacher in a classic school of Sheffield. He prepared for an advanced education by his brother and he also attended Madison University's (now Colgate University) preparatory department in Hamilton, New York from 1846 to 1847.[5][lower-alpha 2] He decided to become a Baptist after hearing an evangelist speak in Sheffield. Rev. John LaGrange baptized him at the old Northeast Baptist Church.[6] He worked as a farmer and a teacher while receiving his education and also attended prayer meetings.[7] He entered Brown University in 1847 and graduated in 1851.[8] He studied alongside his wife at a seminary in Rochester, New York for one year. They also studied together at Newton Theological Seminary and he finished his education there in 1854.[2][9]

Marriage and a child

Simmons met Mary Eliza Stevens when he attended Brown University. Her parents, Deborah and Robert Stevens, were wealthy Quakers from Rhode Island. Mary graduated from a Quaker college with distinction.[10] She became a Baptist after she met Simmons. The couple married on October 28, 1851. Mary was interested in missionary work.[10] She studied Greek and Hebrew at the seminary. Their son Robert was born on December 9, 1854, in Providence, Rhode Island. He became a physician, having graduated from the Homeopathic Medical College in New York.[11]

Career

Minister

After receiving his degree from Brown, and while studying at the seminary, he was a pastor of the Third Baptist Church in Providence, Rhode Island from 1851 to 1854.[2][12] He led the First Baptist Church of Indianapolis beginning in August 1857.[12] In 1861, he left Indianapolis for the Fifth Baptist Church of Philadelphia. Under his leadership a Gothic English style church.[2] He became known for his ability to coordinate fundraising and his abilities as a minister, which was rewarded by two honorary doctorates from two universities.[2]

Simmons witnessed a fugitive slave named West get shot by a deputy marshal and subsequently was captured. He was horrified that the governmental rules were so distant from his Biblical understanding.[12] This led him to deliver a sermon entitled The American Slave System Tried by the Golden Rule and he vowed to act more forthrightly about his beliefs going forward. After he preached that all men are created equal and called out the governor, the church was set on fire. He also received threats.[12] He wrote The Cause and Cure of the Rebellion: How far the people of the loyal states are responsible for the war.[12]

After he retired from the American Baptist Home Mission Society,[2] he ministered to the Old Trinity Baptist Church congregation in New York.[13] He was there from 1874 to 1882.[2]

Post-war mission and schools

Following the end of the American Civil War (1861–1865), there were four million enslaved people who were freed. However, there were no constructs to help build successful lives, like education and opportunities to move out of poverty.[2] He was recruited by the American Baptist Home Mission Society and became the secretary of the Baptist Home Missions.[2][13]

He established schools in the post-war Southern states for freedmen, starting with a Christian school in Richmond, Virginia.[2] He negotiated a $10,000 (~$141,591 in 2021) donation from the Freedmen's Bureau for Colver Institute in 1865. The money was used to purchase the old United States Hotel in Richmond and convert it into a school. Before that, the slave pen called Lumpkin's Jail was rented out and used as a school. In 1876, it was named the Richmond Institute and it was later merged into the Virginia Union University.[2]

He was instrumental in this role in the early development of a number of schools in the south.[14] He helped establish the following schools:[2]

- Benedict Institute (now Benedict College) in Columbia, South Carolina

- Leland College in New Orleans

- Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina

- Wayland Seminary in Washington, D.C.

- the Nashville Institute, now defunct Roger Williams University, in Nashville, Tennessee

- Augusta Seminary in Augusta, Georgia.

He helped establish Morehouse College. He was assigned in 1869 to development of missions among the colored peoples of the South and West and Mexico.

He was a trustee of Brown University.[13] In 1891, Simmons was a founder of Simmons College, now known as Hardin-Simmons University in Abilene, Texas.[12][15] Simmons set up a fund for a library, which was used to build Anna Hall. He donated and catalogued a large number of books for the library.[16]

After working as a minister from 1874 to around 1882, the board of the American Baptist Publication Society elected Simmons as field secretary for the State of New York. He fundraised for Bible and mission work, as well as two more schools. One of the schools became the University of Columbia in Washington D.C. Another was a short-lived school in Indiana.[2]

Death

Mary died on September 24, 1894, and she was buried in a Quaker cemetery near Providence.[17] He died in his home on East 59th Street in New York on December 17, 1905. A service was held at the Fifth Avenue Baptist Church.[18][19] Simmons, Mary, and Robert are all buried in a gravesite on the Simmons College campus[14][15] in the Founders' Cemetery.[20] Simmons once said that he hoped that even their "very ashes may witness for Christian Education."[2]

Notes

- There are unreliable sources that state that his birthday was in 1825 and also 1826, but different months. The biography about Simmons does not supply a date of birth. Census records show that he was born about 1827.

- The biography from the Hardin-Simmons University states that he was at Madison University for three years,[2] but his biography states that he went to Madison in 1846 and entered Brown in 1847.[5]

References

- MacArthur, p. 7.

- "James B. Simmons". Hardin-Simmons University. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- MacArthur, pp. 7–9.

- MacArthur, pp. 9, 12.

- MacArthur, pp. 9, 13, 15, 16.

- MacArthur, pp. 14–15.

- MacArthur, p. 16.

- MacArthur, pp. 18, 23.

- MacArthur, p. 26.

- MacArthur, pp. 27–29.

- MacArthur, p. 30.

- Jaklewicz, Greg. "Civil rights: Hardin-Simmons benefactor James B. Simmons was rooted in abolition". Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- "Rev. Dr. James B. Simmons". Spokane Chronicle. 1905-12-18. p. 8. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- "Obituary for James B Simmons (Aged 78)". Chattanooga Daily Times. 1905-12-19. p. 3. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- "History". History, Hardin-Simmons University.

- "HSU's Only Living Ex-President Relates University's Early Days". Abilene Reporter-News. 1941-04-29. p. 6. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- MacArthur, pp. 30–31.

- "Simmons (James B.)". New-York Tribune. 1905-12-18. p. 7. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- MacArthur, p. 131

- "Headstone of James B. Simmons". The Portal to Texas History. April 1939. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

Bibliography

- Robert Stuart MacArthur (1911). A Foundation Builder: Sketches in the Life of Rev. James B. Simmons, D.D. (PDF). Revelle.