James Bowman Lindsay

James Bowman Lindsay (8 September 1799 – 29 June 1862) was a Scottish inventor and author. He is credited with early developments in several fields, such as incandescent lighting and telegraphy.

James Bowman Lindsay | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 8 September 1799 |

| Died | 29 June 1862 (aged 62) |

| Resting place | Western Cemetery, Dundee, Scotland |

| Alma mater | University of St. Andrews |

| Known for | Pioneer of Incandescent lighting and telegraphy |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | Watt Institute Dundee, Scotland |

| Signature | |

Life and work

James Bowman Lindsay was born in Cotton of West Hills, Carmyllie near Arbroath in Angus, Scotland, son of John Lindsay, farm worker, and Elizabeth Bowman. During his childhood he was trained as a handloom weaver. However at the same time he educated himself and his parents recognised their son's potential. As a result, they saved enough money to be able to send him to St. Andrews University where he matriculated in 1821.[1] As a student he soon made a name for himself in the fields of mathematics and physics and, after completing an additional course of studies in theology, he finally returned to Dundee in 1829 as Science and Mathematics Lecturer at the Watt Institution.

Among his technological innovations, which were not developed until long after his death, are the incandescent light bulb, submarine telegraphy and arc welding. Unfortunately, his claims are not well documented but, in July 1835, Lindsay did demonstrate a constant electric lamp at a public meeting in Dundee, Scotland. He could "read a book at a distance of one and a half feet".[2] However, he did little to establish his claim or to develop the device.

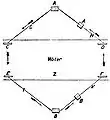

In 1854 Lindsay took out a patent for his system of wireless telegraphy through water. This was the culmination of many years' painstaking experimentation in various parts of the country. The device, however, had an unfortunate flaw. In order to maximise its effectiveness, it was desirable to lay another line on dry land, which exceeded the width of water to be traversed. Although this would have been possible across the Straits of Dover, it would not have been practicable in the case of the Atlantic. A realistic alternative, the use of significantly larger batteries and terminals, was never fully explored.

Aware that the difficulties in laying transatlantic cable had not yet been solved, Lindsay took a great interest in the debate, with the revolutionary suggestion of using electric arc welding to join cables, and sacrificial anodes to prevent corrosion. These ideas, though not entirely new, were not to see widespread practical application for many years to come.

Lindsay was an accomplished astronomer and philologist. In 1858, he published a set of astronomical tables intended to assist in fixing historical dates, which he called his 'Chrono-Astrolabe'.[1] The same year, on the recommendation of Prime Minister Lord Derby, Queen Victoria granted Lindsay a pension of £100 a year. He died on 29 June 1862.

Like Preston Watson, the Dundee pioneer of flight, Lindsay possessed neither the will nor the sheer ruthlessness to promote his innovations as effectively as he might. A deeply religious and humane person, he refused the offer of a post at the British Museum so that he could care for his aged mother.

Lindsay's chief glory lay in his vision, which helped to propel scientific advance through the 19th and 20th centuries. His Lecture on Electricity effectively foretold the development of the information society, and he confidently predicted cities lit by electricity. His concern with electric light was mainly prompted by the need to provide a safe method of illuminating the jute mills, where severe fires had devastated the lives of the workers.

James Lindsay was buried in the Western Cemetery, Dundee.[3] In 1901 a monument, in the form of an obelisk, was erected by public subscription, at his grave. The monument is topped by a bronze hand clasping a lightning conductor.

Obituary

An obituary from The British Millennial Harbinger, page 292, 1 August 1862, provides more information:

- "Departed this life, Lord's day, June 29, 1862 at his residence in South Union Street, Dundee, Mr. J. B. Lindsay. Some of our readers will remember a recent review of a critical and learned "Treatise on the Mode and Subjects of Baptism"[4] which Mr. Lindsay had then just published. On a recent visit to Dundee we had an interesting conversation with the author upon more advanced truths, and a brief inspection of his great and still incomplete work – a Dictionary of 53 Languages, upon which he has labored closely since 1828. He commenced with 150 languages, but in time concluded that three lives would be requisite to its completion and therefore reduced the number. When we saw it, he deemed himself able, if spared, to finish the work within one year. His treatise upon baptism is the work of a scholar, and places before the reader that exhaustive proof that immersion is the one and only action commanded by the Saviour which can only be reached as the result of complete classical research. Recently the author put on the Lord in baptism and cast his lot with brethren who continue steadfastly observing the order of the Lord's house. He was born at Carmullie, in 1799, and commenced life by an apprenticeship to the loom, although at times he would leave his sedentary occupation for the more agreeable one of the plough. By deep application, and by constantly snatching the leisure moments which might present themselves for reading, he acquired considerable knowledge, and began to aspire to a university education, which he obtained at St. Andrews. The study of languages, as well as more abstruse scientific subjects, occupied the chief part of his attention, and to which he applied himself with all his native love of learning. In 1841 he was appointed teacher at the Dundee prison, which appointment he held till he resigned it in 1858. During the whole of this time he scarcely ever moved from his house, except to the prison and back, and the result of a portion of his labors was discovered to his friends in conversations and experiments relating to electrical phenomena, which revealed to them the fact that, alone and unaided – from the sheer force of his genius – he had discovered as early, if not earlier, than Morse or Wheatstone, the principles of the present system of electric telegraphy. Immediately after the public adoption of the present system of land-telegraphy, Mr. Lindsay directed his attention to the sending of messages across water by means of insulated wires, and succeeded – after several trials on ponds and sheets of water in the neighborhood – in establishing on a sure basis the principles of electric communication by means of insulated submerged wires.

- Nor did he stop here – his searching experiments inspired him with the hope of transmitting messages across rivers and seas without the aid of wires, and he so far perfected his invention as to transmit currents across several small pieces of water – the last occasion on which he publicly experimented with this invention being in Portsmouth, about two years ago, when he was highly successful and the results afforded great satisfaction to the scientific gentlemen who assisted. He directed almost every penny he could spare, after procuring the bare necessaries of existence, to the acquisition of philological, as well as scientific and philosophical tomes – and with an income that never till the last few years, we believe, exceeding £50, collected a library of rare and profound works, valued, by competent judges at from £1300 to £1500. At several times however, he was assisted by friends who took an interest in his efforts, and chief among these the present Lord Lindsay. The last gift from this nobleman was a splendid copy of the works of Confucius, in the original, which is said to be the only complete copy of the works of that philosopher in Great Britain.

- Mr. Lindsay's attention was originally riveted on philological studies, owing to doubts which he entertained as to the authenticity of Scripture history – more especially as regarded the origin of the human race from one primal pair: but the more he studied the different languages dead and extant, the more his doubts gave way, and the stronger did his convictions of the truth of the literal exactness of the Scripture statements on this subject become.

- Mr. Lindsay also published what may be called a prelude to the great work to which he has devoted his life – viz.: "The Pentecontaglossal Paternoster," being the Lord's prayer in fifty languages.

- The little time we spent with Mr. Lindsay was enough to enable us to know that profound study had not turned either his head or heart from Christ. He was looking unto Jesus and there is every reason to hope that he will receive a crown of rejoicing at the coming of the Lord."

Gallery

James Bowman Lindsay's diagram for telegraphy across a body of water

James Bowman Lindsay's diagram for telegraphy across a body of water James Bowman Lindsay's obelisk at Western Cemetery, Dundee

James Bowman Lindsay's obelisk at Western Cemetery, Dundee James Bowman Lindsay, Western Cemetery, Dundee, monument inscription

James Bowman Lindsay, Western Cemetery, Dundee, monument inscription James Bowman Lindsay, Western Cemetery, Dundee, monument inscription

James Bowman Lindsay, Western Cemetery, Dundee, monument inscription

References

- "Archive Services Online Catalogue MS 123 Papers relating to James Bowman Lindsay". University of Dundee. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- Letter of Lindsay published in the Dundee, Perth & Cupar Advertiser, 30 October 1835. Reprinted in "A history of wireless telegraphy: including some bare-wire proposals for ..." By John Joseph Fahie, Third Edition, Dodd, Mead & Company, 1902

- For a photo of his grave, see "Western Cemetery – Dundee, Scotland". Retrieved 22 June 2008.

- Lindsay, James Bowman (1861). The British Millennial Harbinger. London: Arthur Hall and Company. pp. 353–355. Retrieved 23 June 2008.

Further reading

- Fahie, John Joseph (1902). A History of Wireless Telegraphy. New York: Dodd, Meade, and Company. pp. 13–32. – The third edition is here.

- Alexander Hastie Millar (1901). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Tim Procter (2004). "Lindsay, James Bowman (1799–1862)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16702. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)