James Greenwood (Australian politician)

James Greenwood (25 August 1838 – 6 November 1882) was an English-born Australian politician.

He was born at Stansfield near Todmorden, West Yorkshire to Richard and Betty Greenwood.

He studied at the University of London, receiving a Master of Arts in theology, philosophy and economics in 1866. John Clifford the Baptist Nonconformist minister and politician was a contemporary.[1]

On 26 June 1866 he married Mary Anne Wallis Ward; they had seven children, of whom four survived to adulthood.

Baptist pastor 1867 - 1876

In 1867 he became pastor at the Stoney Street Baptist Church, Nottingham.

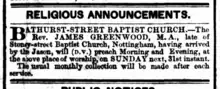

He migrated to Sydney to take up the position of pastor at the Bathurst Street Baptist Church in Sydney, arriving on the Jason on 25 July 1870.[2] He succeeded the Rev James Voller in the parish, as director of the Baptist Training College (1871) and in the residency of the Baptist Union of NSW.[3]

From 1836 – 1938, the Bathurst Street Baptist church was on the northeast corner of Kent and Bathurst Street, where today stands Council House. In 1938, the church moved to its current location at 619 George Street.[4]

In this role he celebrated the marriage of Captain Joshua Slocum and Virginia Walker on 31 January 1871.[5]

In 1874, on a trip to Melbourne,[6] he met Charles Clark[7] and Charles Bright.[8] Clark was a popular pastor at the Baptist church in Albert Street East Melbourne. Clark would go on to resign his ministry for a lucrative career as a public speaker, establishing that profession in Australia. Bright, the sometime editor of Melbourne Punch, moved on to be aspirant politician, campaigning journalist, education reformer and Free thinker.

In several ways, Greenwood’s own career would, with less success, follow these paths.

In 1875, Greenwood returned to Melbourne to preach at the Albert Street Baptist church[9] where his sermons were listened to with 'great attention'.[10]

The Sydney congregation became uncomfortable with their pastor’s involvement in the emerging campaign over State education and requested he choose the campaign or the ministry. Greenwood was also uncomfortable. After his death, the papers reported that he had begun to doubt his calling and he left the ministry with the intention of studying for the Bar, but was diverted from that course by the education campaign and his election to Parliament. [11]

In 1876, he published his 3 valedictory sermons at sixpence each – The damned City’s last warning, All for the best, and Commercial morality – under the title Sermons for the People. His aim he wrote was to impress the leading Christian truths and duties on the minds of his fellow citizens. He retired from his ministry at the end of July 1876.[12]

Journalist & researcher

While still a pastor, Greenwood had begun to write for the Sydney Morning Herald and the Echo.[13]

This was the era before the byline credited the journalist, so it is difficult to identify articles by Greenwood. However, the Northern Star in Lismore referenced an article in the Sydney Morning Herald on Victorian educational progress ‘which some would at once attribute to his pen’.[14]

This article ranged across the capital expenditure of the Victorian Government on State school buildings, the cost of some schools, the cost per pupil served (£5 per head), the school population, the transition from leased to owned schools, the number of acceptable quality school buildings in NSW, comparative attendance as a proportion of population, the amount that NSW would need to set aside to emulate Victoria, and the slow release of funds for schools in NSW (as opposed to the funding made available for roads).[15]

The content of the 3 May article matches the newspaper reports of Greenwood’s education campaign speeches and is consistent with the assessment of his obituary writers.

The Mail described him as an expert in all social and political subjects that could be represented by figures with no rival in the Colonies. They said he had a special gift for statistics and for getting the meaning out of figures. He watched eagerly for the appearance of public documents, which he studied with patient enthusiasm, and compelled them to yield fresh and valuable results to the political thought of the country.

‘Statistical returns of any kind had meanings for him that few other eyes discerned. Ministers and heads of departments feared the consummate skill and untiring energy which he brought to bear upon their reports. The banking corporations had in him the most competent critic they had yet encountered. Some of his statistical articles were revelations to many of those who read them. So he helped to educate many of our politicians. Protectionists, land monopolists, surplus-treasurers, and other jugglers with figures, had their carefully constructed balloons fatally pricked by his sharp and watchful pen.’[16]

It was also said that many of the statistical returns issued by the Government had been greatly improved following his suggestions and that the inaugural role of Government statist would have been offered to him if he had wanted it.[17]

Greenwood’s public opponents claimed he was more than just a journalist on the staff of the SMH.

The proposed Illawarra Railway was a campaign issue when Greenwood stood in the election of 1887. The Illawarra Mercury asserted 'Mr. Greenwood is intimately connected with the Sydney Morning Herald, if not at the very head of its editorial staff. On all occasions, and in every possible way, the Herald has opposed the Illawarra Railway, and will probably do so to the end, and if it should transpire that Mr. Greenwood will support the project while he is connected with that paper, it will be a matter for general surprise, and will greatly add to the high estimation in which he is now held by the people of this colony as a public man.'[18]

In the 1882 electoral confrontation between Sir John Robertson and Greenwood over the seat of Mudgee, Robertson claimed that it was Greenwood’s patrons at the SMH who had promised to bankroll Greenwood's campaign and that it was because the paper had withdrawn the promise of funding that Greenwood had to withdraw from the campaign ignominiously.[19]

That there might be something to these claims is suggested by the presence in the small group at Greenwood’s funeral of the editor of the SMH Dr. Andrew Garran, (Editor 1873-1885)[20] and Mr. E. Lewis Scott, the paper’s dramatic and musical critic.[21]

At least one article appeared under Greenwood’s name – The Equality of the Sexes.[22] In which he argued for greater (though not complete) equality, opposing the views in Sir William Hamilton’s Metaphysics and referencing John Stuart Mill.

Must we for ever go on educating our daughters with no other hope but that in time somebody will come to marry them ? What a degradation of woman to make that her only prospect in life 1 Why not multiply the avenues of feminine industry and give our daughters as good chances of independence as our sons ? There is no need to make them rivals in the avocations of life, because nature has given them certain distinctive adaptations^; but, whatever a woman can do as well as a man, there is no reason in nature, and there ought to be no reason in social life, why she should not be as free as a man to do it.

In the words of the Sydney Morning Herald. 'He was a man of great breadth and variety of knowledge, of extensive reading and patient research, and of scholarly tastes.'[23]

Secular education campaigner

While pastor he became a prominent campaigner for National, Secular, Compulsory and Free education. In 1874 he helped found the NSW Public School League, writing its manifesto and other publications. To further this campaign, he resigned from the Baptist ministry in 1876.

This campaign achieved most of its aims in the NSW in the Public Instruction Act 1880, namely government control, compulsory and secular. Later reforms ended government funding of church schools (1882) ended and removed fees (1906).[24]

Politician

In 1877 he was elected to the New South Wales Legislative Assembly for East Sydney, but he did not re-contest in 1880.

Death

Greenwood died of an overdose of chlorodyne at the age of 44 at Paddington on 6 November 1882, survived by his wife and three children.

He is buried at Rookwood Cemetery.

The Mitchell Library holds records of his writing and speeches mostly related to his campaign to reform education.[3][25][26]

References

- "John Clifford". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- The Sydney Morning Herald Wed 27 Jul 1870

- Burn, Kerrie (1 April 2006). "The Australian Baptist Heritage Collection". ANZTLA EJournal (58): 28–33. doi:10.31046/anztla.v0i58.1308. ISSN 1839-8758.

- "Central Baptist Church". www.sydneyorgan.com. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- SLOCUM—WALKER—January 31, by the Rev. James Greenwood, Captain Joshua Slocum, ship Constitution, Boston, Mass. U.S., to Virginia Albertina, daughter of William H. Walker, Survey Department. The Sydney Morning Herald Friday 24 Feb 1871

- The Sydney Morning Herald 19 Oct 1881

- "Charles Clark, Australian Dictionary of Biography".

- "Charles Bright, Australian Dictionary of Biography".

- "Former Baptist Church House".

- The Age, 25 January 1875

- The Sydney Morning Herald 30 Nov 1882

- The Sydney Morning Herald 17 Jun 1876

- An evening paper and another Fairfax title (1875-1893).

- Northern Star 20 May 1876

- Sydney Morning Herald 3 May 1876

- The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser 11 Nov 1882

- The Argus 14 Nov 1882, The Sydney Morning Herald 30 Nov 1882

- Illawarra Mercury 16 Nov 1877

- Sydney Morning Herald 14 January 1882

- "Andrew Garran, Australian Dictionary of Biography".

- The Sydney Morning Herald 2 October 1909

- Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser 10 January 1880

- The Sydney Morning Herald 30 Nov 1882

- "Free, compulsory and secular Education Acts". DEHANZ. 1 March 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- Morris, David, "Greenwood, James (1839–1882)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 12 September 2023

- "Mr James Greenwood (1838-1882)". Former members of the Parliament of New South Wales. Retrieved 8 June 2019.