James W. Watts

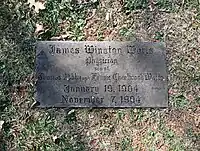

James Winston Watts (January 19, 1904 – November 15, 1994) was an American neurosurgeon, born in Lynchburg, Virginia. He was a graduate of the Virginia Military Institute as well as the University of Virginia School of Medicine. Watts is noteworthy for his professional partnership with the neurologist and psychiatrist Walter Freeman. The two became advocates and prolific practitioners of psychosurgery, specifically the lobotomy.[1] Watts and Freeman wrote two books on lobotomies: Psychosurgery, Intelligence, Emotion and Social Behavior Following Prefrontal Lobotomy for Medical Disorders in 1942, and Psychosurgery in the Treatment of Mental Disorders and Intractable Pain in 1950.

James W. Watts | |

|---|---|

Walter Jackson Freeman II (left) and Watts (right) studying an X ray before a psychosurgical operation, photo published in May 1941 | |

| Born | January 19, 1904 Lynchburg, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | November 15, 1994 (aged 90) |

| Education | |

| Known for | Worked as Walter Freeman's surgeon contributing to the popularization of Lobotomy in the United States |

| Medical career | |

| Profession | |

He is also known for carrying out the lobotomy of Rosemary Kennedy under the supervision of Freeman. Kennedy's mental capacity diminished to that of a two-year-old child. She could not walk or speak intelligibly and was considered incontinent.[2]

Career

After completing medical school in 1928, Watts worked as a research fellow at Yale before joining the faculty of the Department of Neurosurgery and Neurological Surgery at The George Washington University Hospital in 1935. He remained in this position until his retirement in 1969.

Watts was recruited into a medical partnership by his colleague Walter Freeman, who needed the collaboration of a trained surgeon in order to practice the leucotomy, a technique pioneered by the Portuguese neurologist António Egas Moniz. In the procedure developed by Moniz, the "white matter" in the frontal lobes was severed using a leucotome, an instrument Moniz designed specifically for the procedure. Freeman and Watts acquired several of the instruments and performed their first operation in 1936. They eventually modified the procedure to sever more of the white matter, and renamed it lobotomy in order to distinguish it from the earlier procedure developed by Moniz. Their technique soon became the standard form of the operation, and was known as the "Freeman-Watts Procedure".[3]

Watts' colleague, however, was less conservative and sought other ways to access the frontal lobes of the brain without the complications associated with conventional brain surgery. Inspired by the work of the Italian psychiatrist Amarro Fiamberti, Freeman developed, without the knowledge or participation of Watts, a procedure for reaching the frontal lobes by inserting a probe under the eyelid and above the tear duct, then hammering it through the thin bone of the eye socket. The instrument was swished around, severing the white matter, and was then repeated on the other side. The whole operation took only minutes under local anesthesia or by using an electroshock machine to render the patient unconscious by passing a large electrical current through the brain, inducing a seizure, then leading to a brief period of post-seizure coma, which was when the procedure would be carried out. This new procedure became known as the transorbital lobotomy, also dubbed the "ice pick lobotomy" because the instrument used, an orbitoclast, was very similar to a common ice pick. The new procedure also signaled the end of the professional relationship between Freeman and Watts. After performing the new procedure by himself on ten patients, Freeman finally revealed to Watts what he had been doing. Watts, unlike Freeman, was a trained neurosurgeon and adamantly believed lobotomy should be performed only by a proper surgeon.[4] He insisted that Freeman cease performing operations alone, but it was to no avail and Watts soon left the practice that he had jointly established with Freeman.

The 1950s saw the introduction of the first truly effective antipsychotic medications, notably Thorazine. This, combined with a growing discomfort among the medical profession and general public regarding lobotomy, led to a sharp decline in the use of the procedure. In the intervening years, the theoretical basis of lobotomy has been largely discredited.

Watts retired in 1969, but continued his association with The George Washington University Hospital until the late 1980s.

Personal life

Watts was born in 1904 in Lynchburg, Virginia. He had two children with wife Julia Harrison Watts. He died in 1994.

References

- Dr. James Watts, 90, Pioneer In Use of Frontal Lobotomy, Tim Hilchey. The New York Times, November 11, 1994.

- Henley, John (August 12, 2009). "The Forgotten Kennedy". theguardian.com.

- George Washington University

- Valenstein, Elliot (1986). Great and Desperate Cures: The Rise and Decline of Psychosurgery and Other Radical Treatments for Mental Illness. ISBN 0465027105.

- The GW; Foggy Bottom Historical Encyclopedia. "Watts, James W." The George Washington University. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- "Guide to the Walter Freeman and James Watts Papers, 1918–1988". Special Collections Research Center, The George Washington University. Retrieved 2014-03-25.

- Kopell, Brian H., Machado, Andre G., Rezai, Ali R (2005). "Not Your Father's Lobotomy: Psychiatric Surgery Revisited". Clinical Neurosurgery. Congress of Neurological Surgeons. 52: 315–330. PMID 16626089. Archived from the original on 2012-02-06. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jansson, Bengt. "Controversial Psychosurgery Resulted in a Nobel Prize". Nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 2010-01-09. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- The Obituary Page. "Science, 1994". Retrieved 2009-12-07.