Jan Claudius de Cock

Jan Claudius de Cock[1] (Brussels, baptized on 2 June 1667 – Antwerp, 1735)[2] was a Flemish painter, sculptor, print artist and writer.[3] De Cock produced both religious and secular sculpture on a small as well as monumental scale. De Cock completed many commissions in the Dutch Republic. He worked on decorations for the courtyard of the Breda Palace for William III, King of England, Ireland, and Scotland and stadtholder.[2] He is credited with introducing neoclassicism in Flemish sculpture.[4] He was a prolific draughtsman and designed prints for the Antwerp publishers. As a writer, he wrote a poem about the 1718 fire in the Jesuit Church in Antwerp and a book of instructions on the art of sculpture.[5]

Life

De Cock was the son of the sculptor Claudius de Cock and Magdalena van Havré.[6] In the guild year 1682-1683 he was registered at the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke as a pupil of Pieter Verbrugghen the Elder.[7][8] Verbrugghen operated one of the foremost sculpture workshops of Antwerp, which supplied local churches and international clients with a variety of statuary, church furniture and architectural decorations.[9]

_-_Asia.jpg.webp)

He was admitted as a master of the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke in the guild year 1688-1689.[8][10] Nevertheless, Joannes Claudius de Cock continued to work for some time in the studio of Peter Verbrugghen the Younger (c. 1640-1691), son of his master Pieter the Elder and brother of Hendrik Frans Verbruggen (1654-1724). Only after the death of Peter Verbrugghen the Younger in 1691 did he establish himself as an independent sculptor.[5]

From 1692 onwards, he was commissioned by King and Stadholder William III to execute the sculpture for the interior and exterior of the Prinsenhof in Breda, a project which was under the direction of Jacob Romans. De Cock decorated an interior staircase with foliage and animal figures, created two fireplaces, a mirror frame and a statue of Mars. In addition, stone and wooden sculptures by his hand were placed in various apartments. During his activities in Breda, he was given temporary residence and working space at the local government's location. There he also gave lessons in drawing.[10] He carved the 'William and Mary' ceiling and made a series of busts of the Princes of Orange, including of Prince Philip William and Prince Maurice.[4][11][12] As far as is known, nothing has been preserved of de Cock's works at Breda Castle.[10]

On 13 January 1693, he married Maria Clara Serlippens, the daughter of a merchant. In 1694 the couple's first child was born in Breda, followed by a second in 1696. More children were born of whom 3 died in childhood. De Cock was reportedly small in stature.[13] In his sketch regarding de Cock included in his biographies on Dutch and Flemish artists, the serial vilifier Jacob Campo Weyerman went so far as to compare him to a dwarf. Weyermans also alleges without evidence that the de Cocks had a troubled marriage. Nevertheless, at their 25th wedding anniversary de Cock published a eulogy to marriage. While living in Breda, de Cock worked on the decorations of the courtyard of the Breda Palace for King William III with the assistance of his brother-in-law Melchior Serlippens and seven or eight pupils.[2][14]

By around 1697, Jan Claudius de Cock had moved back to Antwerp, where he resided for the rest of his life. He operated a large workshop where he employed many assistants and trained 16 pupils in sculpture and drawing.[10][15] The latter also studies modeling with the aim of a career as a silversmith.[5]

He had close contacts with the Antwerp printers as shown by the bust he made of Balthasar III Moretus, the manager of the Plantin Press and the designs he made for the Plantin Press.[5]

After a productive career, De Cock died in Antwerp in early 1735. It is likely that his estate was insolvent as his daughter soon after his death travelled to The Hague to sell, with mixed feelings, some of his marble sculptures and models.[6]

Work

General

De Cock was a prolific and versatile artist who worked on a wide range of church furniture such as altars, choir stalls, confessionals, pulpits and tombs, as well as secular items such as garden statues and vases, designs for cradles, clocks, floats, reliquaries and monuments.[6] In addition, he also produced smaller scale sculptures and portrait busts.[14] He was a prolific draftsman and was sought after as a teacher of drawing and sculpting. He created designs for the frontispieces and illustration of publications of the Antwerp printers. He produced a few prints of his own. While he was described by Weyermans as a painter, no known paintings by his hand are known. He wrote poems on occasional subjects as well as a manual of sculpture in rhyme.[4]

Sculpture

De Cock worked in many materials including marble, stone, bronze, wood and terracotta.[10] His style shows the influence of the late Baroque works produced by the workshop of his master Verbrugghen. He also admired sculpture from the Antique and the work of his compatriots François Duquesnoy and Artus Quellinus the Elder.[16] This is reflected in the tendency towards Classicism in his work.[4]

_-_Bust_of_a_young_moor_with_a_medallion_representing_Rudolf_II_(2).jpg.webp)

He known for his allegorical representations of children. An example are a pair of terracotta figures representing Air and Fire. The Africa boy stands for the element Fire because of the association of black people with the heat of the African sun.[17] The statues may also be allegorical representations of the continents Europe and Africa. They were likely created as workshop models for larger stone and marble compositions. These terracotta models appealed as individual works of art and were collected by contemporary collectors.[18] Among his allegorical representations of children are a few busts and statues of African boys, such as the African boy with a crown in the form of a fortress (1704, Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam),[19] the marble Bust of a black boy (1705–10, Victoria and Albert Museum)[14] and the bronze Bust of an African Boy (Walters Museum). There have also been a number of similar busts attributed to de Cock sold on the art market. These busts may have been based on a particular individual but were also intended to represent a general type of the African[20] The African boys typically wear on their chest a medallion, showing a portrait or a symbol. These were likely connected with the particular preference of the patron for whom the sculpture was produced. For instance, the medallion on the bust in the Victoria and Albert Museum represents a cardinal's hat. This suggests that the boy represented a cleric's page and that the bust was likely commissioned by a cardinal.[21]

De Cock also made a set of four sculpture groups representing the four continents (Princeton University Art Museum). The set once were in the collection of the American statesman Elias Boudinot IV (1740–1821). The continents are personified by women shown with bear attributes characterizing each continent and its peoples. Europe features a domed temple, papal crown, books, arms and armor, grains, flowers and a horse. These symbolized Europe's religious, cultural and military achievements and its abundant resources, which in the European ideology of that time was deemed to reflect the Christian God's favor.[22] Another allegorical group is the Allegory of War and Peace (Stedelijk Museum Breda), a terracotta sculpture, which was possibly created at the time of the peace talks in the War of the Spanish Succession held in 1710 in Geertruidenberg.[23][24] An example of the work he did for the Princes of Orange in the Dutch Republic are the bas reliefs with the mythological scenes of Alpheius and Arethusa and Apollo en Daphne, both signed and dated 1707. They are located in the house at the Korte Vijverberg 3, The Hague, where the Dutch cabinet holds its meetings. These companion pieces depict scenes of mythological lovers taken from Ovid's Metamorphoses.[25][26]

Many of de Cock's commissions were for church furniture and decoration as well as tomb monuments. He made in 1713 Caryatids for the choir stalls of the former priory of Corsendonk in Oud-Turnhout, today partially displayed in the collegiate St. Peter's Church in Turnhout.[27] They are the most striking example of the classicist streak in de Cock's work. He was able to incorporate his medallions and caryatids into the back panel in a soberly harmonious manner, so that the balance between architecture and sculpture was restored. Some of the elegant figures in the choir stall are executed in the late Baroque style, others in a restrained classical manner.[28]

De Cock was one of the artists who worked on the creation of a group of statues referred to as the Calvary on the outside of the St. Paul's Church in Antwerp. Its overall design dates from 1697. In 1734 construction of the Calvary was completed but further statues were added up to 1747. It is built as a courtyard and leans on one side against the south aisle of the church and the Chapel of the Holy Sacrament. The structure includes 63 life-size statues and nine reliefs executed in a popular and theatrical style. The statues are arranged into four groups: the angel path, which ascends to the Holy Sepulcher, the garden of the prophets on the left, the garden of the evangelists on the right and the Calvary itself, which consists of an elevated artificial rock, divided into three terraces, on which statues are placed with Christ on the cross at the top.[29] Most statues are of white stone with some made of wood. Some statues are dated or signed. The principal sculptors were de Cock, Michiel van der Voort the Elder and Alexander van Papenhoven with some statues by the hand of Jan Pieter van Baurscheit de Elder, Willem Kerricx and his son Willem Ignatius Kerricx and anonymous collaborators. De Cock also sculpted a number of the statues, 12 of which are signed and 5 of which are attributions. These include various angels carrying symbols of Christ's Passion, various biblical figures as well as a penitent Maria Magdalen.[30][31]

Graphic work

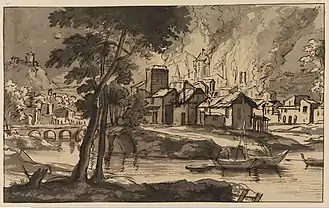

De Cock was a prolific draughtsman who left an extensive body of drawings. Many of these were studies for his sculptures or other objects such as garden vases and cradles. Some were artworks in their own right such as the Burning city by a river (Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum).[32] Others were designs for illustrations made for the Antwerp printers. We now know that no fewer than five engravers turned his designs into prints, including Jan Antoni de Pooter,, Petrus Balthasar Bouttats, Hendrik Frans Diamaer, Jan Baptist Jongelinck and Norbert Heylbrouck the Elder.[5]

He designed the title page and 17 illustrations for the Breviarium Romanum published by Balthasar IV Moretus first in 1707. The Antwerp engraver cut the plates for the publication. In 1706 and 1708 he provided the design for the title page of the Syntagma de annulis historico-symbolicum. Authore R.P. Francisco Curtio Augustiniano Brugensi (...) and a portrait of the eighty-one-year-old artist biographer Cornelis de Bie, which were both engraved by Hendrik Frans Diamaer.

He made several prints of which only two are known, one an etching of the Martyrdom of Saint Quirin of Neuss and the other a woodcut representing Psyche in clair obscur.[5] He had apparently learned his printmaking techniques from his study of the, which appeared in Dutch translation of Abraham Bosse's 1645 Traité des manières de graver en taille-douce (Treatise on Line Engraving) published in Amsterdam in 1662 as Tractaet in wat manieren men op root koper snijden ofte etzen zal (…). A copy of the book with de Cock's name inscribed in it was found in his collection.[5]

Writings

He also wrote treatises on art and poems.[4] In 1720 he wrote a treatise on sculpture entitled Eenighe voornaemste en noodighe regels van de beeldhouwerye om metter tydt een goet meester te worden (Some principal and necessary rules of sculpture to become a good master with time). This manual was written in verse and contained practical instructions for sculptors aiming become a good master over time.[6] In the book he also takes the opportunity to criticize the training at the academy of Antwerp. The question is, however, whether this was merely based on the quality of the teaching, are was also driven by selfish motives. Master sculptors often relied on apprentices to help in the projects of their workshops. By educating new sculptors in the academy, this important resource was lost to the master sculptors.[5]

References

- Alternative name spellings and versions: Jan Gelauden de Cock, Jan Claudius de Cocq, Jan Claudius de Cocx, Jan Claudius de Kock, Gelaude de Cock, Joannes-Geloude de Kock

- Jan Claudius de Cock at the Netherlands Institute for Art History (in Dutch)

- Bower, James M.; Getty, Murtha B. (1994). Union List of Artist Names: Aa-Dzw. Cengage Gale. p. 572. ISBN 978-0-8161-0725-4. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- Cynthia Lawrence. "Cock, Jan Claudius de." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 9 May 2021.

- W. Nys, Joannes Claudius de Cock als ontwerper van boekillustraties: een overzicht, De Gulden Passer 73 (1995), p. 155–186 (in Dutch)

- Dennis de Kool, Jan Claudius de Cock (1667-1735) en zijn tekeningen van tuinbeelden, in: Cascade: bulletin voor tuinhistorie, Jrg. 23. no. 2 (2014), pp. 13-36 (in Dutch)

- Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art; Ward, Roger B.; Philbrook Art Center (June 1996). Dürer to Matisse: master drawings from the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Cummer Museum of Art, Hood Museum of Art. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-942614-27-5. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- Ph. Rombouts and Th. van Lerius (eds.), De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche sint Lucasgilde Volume 2, Antwerp, 1864, pp. 318, 493, 495, 531, 537, 606, 607, 626, 632, 678, 685, 689, 691, 713, 727, 742, 744, 866 (in Dutch)

- Pieter Verbruggen at the Netherlands Institute for Art History (in Dutch)

- Dennis de Kool, De verloren strijd van Mars. De beeldhouwkunst van Jan Claudius de Cock en Jan Baptist Xavery in Breda, Jaarboek 'de Oranjeboom' 70 (2017), pp. 161-173 (in Dutch)

- Harris, John (2007). Moving rooms. Yale University Press. pp. 291–. ISBN 978-0-300-12420-0. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- Jeroen Grosveld, 'De Oorlog' van Jan Claudius de Cock' Archived 2014-03-04 at the Wayback Machine (in Dutch)

- Fernand Donnet, Un oeuvre intime du sculpteur J.C. de Cock, in: Annales de l’Académie Royale d’Archéologie de Belgique, 65 (1913) pp. 249-254 (in French)

- "Bust of a black boy, Jan-Claudius de Cock". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- His pupils included: Jan Frans Meskens, Jan Karel van Bueghen and Michiel Hennekin in 1697; Frans Goubau in 1700; Daniel Govaerts in 1701; Guillielmus van Boeck in 1711; Jan Baptist Buys in 1712; Jacobus de Wolf in 1713; Joannes van Hoostenryck in 1714; Francis van Paesschen and Jan Peter de la Porte in 1718; Lowis Bertolis de Laen, Pieter van den Bosch, Christiaen van der Wee and Mertinus Joseph le Gandermes in 1721; Martinus Lauwers in 1725

- Wim Nys, Tekenen en boetseren om zilversmid te worden, 2009 (in Dutch)

- Black is beautiful: from Rubens to Dumas Exhibition: 26 July - 26 October 2008 at Codart

- Jan Claudius de Cock, Pair of Figures Representing Air and Fire at Sotheby's

- Blakely, Allison (1 March 2001). Blacks in the Dutch World: The Evolution of Racial Imagery in a Modern Society. Indiana University Press. pp. 129–130. ISBN 978-0-253-21433-1. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- Jan Claudius de Cock, Bust of an African Boy at the Walters Museum

- Attributed to Jan Claudius de Cock (1667-1735), Flemish, circa 1700, Bust of a Cardinal's page at Sotheby's

- Jan Claudius de Cock, Europe at the Princeton University Art Museum

- Bellum / Oorlog en Vrede at Brabants Erfgoed (in Dutch)

- "Kunstzalen A. Vecht". TEFAF Maastricht. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- "Jan Claudius de Cock – Alpheius and Arethusa (1707)". cedargallery.nl. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- Iris Kockelbergh. "Verbrugghen." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 14 May 2021.

- Baisier, Claire; Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten (Belgium) (2000). 17th and 18th century drawings: The Van Herck collection. King Baudoin Foundation. p. 188. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- Helena Bussers, De baroksculptuur en het barok Archived 2021-04-10 at the Wayback Machine at Openbaar Kunstbezit Vlaanderen (in Dutch)

- De Inventaris van het Bouwkundig Erfgoed, Sint-Pauluskerk en dominicanenklooster (ID: 4648) (in Dutch)

- Rudi Mannaerts, Saint Paul's, the Antwerp Dominican church, a revelation, Toerismepastoraal Antwerpen

- 'The calvary garden: on a pelgrimage ’round the corner’', Toerismepastoraal Antwerpen

- Jan Claudius de Cock, Brennende Stadt an einem Fluss at the Kupferstichkabinett, Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum (in German)

External links

Media related to Jan Claudius de Cock at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Jan Claudius de Cock at Wikimedia Commons