Jan van der Croon

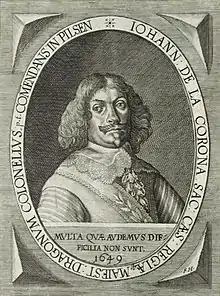

Jan van der Croon (c. 1600 – 6 November 1665), also called Jan della Croon, Johann de la Corona, or von der Cron, was a Dutch professional soldier and military commander in Spanish and Imperial service who reached the rank of lieutenant field marshal. Rising from a common soldier to an important officer, regiment holder, and city commander during the Thirty Years' War, he continued his career after the Peace of Westphalia in the military administration of Bohemia. For many years until his death, he served as city commander of Prague and vice military commander of Bohemia, strengthening fortifications and recruiting soldiers for the Second Northern War and the Austro-Turkish War.

Jan van der Croon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Military commander of Plzeň | |

| In office 1645–1650 | |

| Military commander of Prague, vice military commander of Bohemia | |

| In office 1652–1665 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1600 Weert |

| Died | 6 November 1665 Prague |

| Resting place | St. Thomas' Church, Prague |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service years | 1624–1665 |

| Rank | Lieutenant field marshal |

| Battles | Eighty Years' War Siege of Breda, 1624; Siege of Leuven; 1635; Siege of Schenkenschans, 1635 War of the Mantuan Succession Sack of Mantua, 1630 Thirty Years' War Rain, 1632; Alte Veste, 1632; Lützen, 1632; Siege of Regensburg, 1634; Nördlingen, 1634; Recapture of Lubin, 1640; Siege of Hirschberg, 1640; Siege of Görlitz, 1641; Battle of Schweidnitz, 1642; Raid on Litovel, 1642; Breitenfeld, 1642; Blockade of Głogów, 1644; Capture of Kiel, 1644; Blockade of Eger, 1647 |

Croon also became an ennobled landowner and patron to the Catholic church in Bohemia. He was one of the few soldiers of his time to rise to the rank of general despite non-noble descent, a characteristic he shares with cavalry general Johann von Werth with whom he was often confused with.

Life

From soldier to officer

.jpg.webp)

Jan van der Croon was born in the town of Weert in the Spanish Netherlands into the Cool or Coolen family, also called Croon after the inn De Croon in their property. The exact identity of his parents is not clearly identifiable. The temporary Weert mayor Jacob in de Croon was probably Jan's uncle,[1] but is also classified as his father in some sources.[2] His two brothers Franz (Frans) and Willem also became soldiers, Franz was a captain in imperial service[3] and Willem fell as a lieutenant colonel in Spanish service at Lille.[4]

Jan began his military career in 1624 in the Spanish army fighting the Netherlands in the Eighty Years' War. His role model was presumably his uncle Giel Jonghen d'Ongarie, who also fought as a soldier in Habsburg service.[3] Jan was usually referred to by his contemporaries in the army by the surname de la Corona.[1] Under Ambrosio Spinola, Croon took part in the siege of Breda from August 1624 until the city's surrender in early June 1625. Shortly after, he transferred to the Imperial army as a pikeman and served under Albrecht von Wallenstein in his Hungarian campaign against the Protestant commander Ernst von Mansfeld and the Holstein campaign against the Danes. In 1629, Croon moved to northern Italy with the imperial army under Ramboldo Collalto to support Spain in the War of the Mantuan Succession. In July 1630, he participated in the storming and sack of Mantua. Croon attracted the attention of his superiors and was promoted to corporal while his uncle Giel fell near Mantua as a lieutenant colonel.[3]

Returning from Italy after the Peace of Cherasco in June 1631 with the corps of Johann von Aldringen, Croon joined the combined Imperial and League army under Count Tilly in October. In April 1632, Croon fought in the Battle of Rain against the Swedes advancing towards Bavaria, in which the Catholic League army was defeated and Tilly was mortally wounded. Croon then fought under Wallenstein both at the Alte Veste, after which he was promoted to lieutenant, and at the Battle of Lützen, in which the Swedish king Gustavus Adolphus fell. After Wallenstein's assassination in early 1634, Croon again served under Aldringen. During the siege of Regensburg, he fell wounded into enemy captivity, but was able to escape by himself. At the end of July, Regensburg surrendered to the imperial forces, shortly after Aldringen had fallen in skirmishes against a Swedish relief army near Landshut. Croon next fought in the Battle of Nördlingen in September, where the Swedes were decisively defeated. Then, he was promoted to captain in the dragoon regiment of Ottavio Piccolomini.[3]

With Piccolomini's troops, Croon moved to the Southern Netherlands in support of the Spanish. In July 1635, he took part in the successful relief of Leuven and the capture of Schenkenschanz. He participated in two operations in the winter to supply the fortress, which was subsequently besieged by Dutch troops. For his actions, he was promoted to Obristwachtmeister in Johann Wilhelm von Kuefstein's dragoon regiment. The regiment spent the next year either in Bohemia or Saxony. After Kuefstein's death in early May 1637, Croon became the interim commander of the regiment. From its base at Oschatz, it made several raids on the Swedes, some led by Croon himself, capturing 300 horses and several officers.[3]

The main imperial army under Matthias Gallas, returning from Burgundy, attacked the Swedes under General Banér in mid-June at Torgau. Banér narrowly escaped and retreated to Pomerania. Alongside Gallas' army, Croon pursued the Swedes and took up quarters in Mecklenburg. For his achievements in this campaign, he received the next promotion to lieutenant colonel. Throughout 1638, he stood in Mecklenburg against the Swedes who were trapped in Pomerania. At the end of the year, Swedish reinforcements and the disastrous supply situation forced the imperial forces to retreat. During the retreat, Croon and Generalwachtmeister Bruay crushed two Swedish regiments at Boizenburg on the Elbe. Over the winter, Croon's troops were sent to quarters in Silesia. Here, he remained in action in the following years, defending the region against Swedish attacks.[3]

Regiment owner and city commander

In 1640, Croon distinguished himself in the recapture of the castle and town of Lubin, and was proposed for promotion by his superior Martin Maximilian von der Goltz. On 28 August 1640, Emperor Ferdinand III appointed Croon colonel and commander of the previous dragoon regiment D'Espaigne, whose previous holder had died.[5] Croon had thus risen to become one of the few non-noble regiment holders. From then on, he earned money directly from its operations as a war contractor.[3] With the regiment, he took part in the siege of Hirschberg in September 1640 and the recapture of Görlitz during the summer of 1641. At the end of May 1642, under Franz Albrecht of Saxe-Lauenburg, he participated in the failed relief of the Swedish-besieged fortress of Schweidnitz, during which Franz Albrecht was captured and mortally wounded. Croon escaped capture and subsequently led several successful attacks on the Swedes who had moved into Moravia, including a raid on the Swedish garrison of Litovel on 5 July. After the imperial army had pushed the Swedes out of Moravia and Silesia, Croon and his dragoons fought on the right wing of the imperial forces at the defeat of Breitenfeld in November.[5]

In May 1643, Croon was ordered by the new commander-in-chief Gallas to take up a position with his and Gallas's own dragoon regiment between Poděbrady and Nymburk in northern Bohemia against the invading Swedes to prevent them from crossing the Elbe and advancing towards Prague.[6] The Swedish army under Lennart Torstensson was able to cross the Elbe with a pontoon bridge at Mělník in early June, but did not advance against Prague, instead moving via Kolín to Moravia.[7] After the Swedish army left for a surprise attack on Denmark at the end of the year, Croon and his regiment were sent to Silesia to blockade the Swedish-occupied fortress of Głogów.[5] In March 1644, he captured Herrnstadt Castle on the outskirts of Głogów.[6]

With the main imperial army under Gallas, Croon and his regiment moved as far as Holstein in June 1644 in support of the Danes. In August, he took part in the storming of Swedish-occupied Kiel.[3] Shortly afterwards, the Swedes under Torstensson bypassed the imperial army to the south and threatened Saxony as well as Bohemia with an advance along the Elbe. Gallas had to go back with his army through the devastated country and took up camp near Bernburg to cover Saxony against the Swedes. However, the army was soon surrounded and starved by the superior Swedish cavalry. Croon was involved in several engagements with the Swedes on the retreat, and was hit in the arm by a musket ball near Bernburg.[6][3]

.jpg.webp)

As a result of the injury and the unfortunate campaign, from the Bernburg camp, he asked his former commander Piccolomini for another use for himself and his regiment. Piccolomini, by now in Spanish service, recommended him in December to Walter Leslie at the Viennese court for a new function.[3] In January 1645, Croon was back in Bohemia and stationed as city commander in Plzeň. He was thus able to leave active field service. A part of his regiment under Bartolomeo Strassoldo was placed in Pardubice and successfully defended this city against Swedish attack attempts in October.[6] Plzeň also withstood the Swedes; Croon remained stationed there for the following years and had the city's neglected defences greatly expanded.[3]

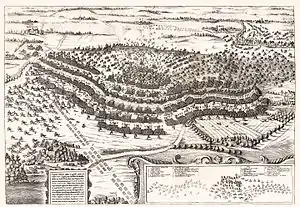

In August 1647, Croon and his regiment supported the imperial reconnaissance in the run-up to the cavalry skirmish at Triebl. His regiment and two Croatian regiments ordered to Plzeň made it possible for the imperial forces under General Holzappel to know exactly about the Swedish movements and to inflict losses of over 1,000 men on the Swedes at the nearby village of Triebl on 22 August. In the run-up to the battle, Croon had also had additional powder made for the army in Plzeň on Holzappel's instructions.[8] On 25 October 1647, shortly after the departure of the main imperial army, Croon recaptured the Königswarter redoubt outside Eger from the Swedes. He was then to blockade the Bohemian border town and fortress of Eger, which had been captured by the Swedes in July, in order to win it back by starvation, but he was not able to completely seal off the town until the onset of winter.[9] Eger was close to falling when the Swedes sent General Königsmarck with a large amount of cavalry to relieve it at the end of March 1648. Königsmarck broke through Croon's blockade between Wunsiedel and Waldsassen, bringing 300 wagons of provisions and 100 head of cattle to the starving town on 6 April.[10]

Although Croon had reinforced Elbogen and Falkenau against possible Swedish attacks on order of Emperor Ferdinand III, Königsmarck conquered Falkenau in June 1648 after several days of shelling. However, he found Elbogen too strongly fortified and withdrew from there.[11] On 22 July, Königsmarck surprisingly appeared in front of Plzeň with 2,500 horsemen. He did not attack the city, but rode on to Bělá nad Radbuzou, where he picked up 600 infantrymen. Croon's garrison was not strong enough to effectively hinder Königsmarck in his actions. The latter moved with his entire troop via Rakovník to Prague, which he attacked by surprise on 26 July, capturing the Lesser Town.[12] The Peace of Westphalia at the end of October ended the fighting in Bohemia. In the subsequent downsizing of the imperial forces, all dragoon regiments were disbanded except Croon's own.[3]

General and Bohemian military commander

After the end of the Thirty Years' War, Croon remained in imperial service. Together with his patron Piccolomini, he took part in the Nuremberg Execution Day as an imperial plenipotentiary from 1649 to 1650.[2] To enforce the provisions made for troop withdrawals, he was charged with securing the withdrawal of foreign troops in Erfurt and other still Swedish-occupied towns from June to October 1650. In October, he was appointed commander of Eger and finally in November of the same year, he was elevated to the Bohemian nobility and raised to the rank of baron under the name Johann Freiherr von der Cron. Until then he had called himself Jan de la Croon.[1] In 1651, he acquired landed property in Bohemia with the village of Zahořany near Litoměřice and its surroundings,[13] and was awarded the title of Hofkriegsrat. The next year, he was appointed commander of Prague and vice military commander of Bohemia, as well as promoted to the rank of Generalfeldwachtmeister. In 1653, he became the owner of the former Waldstein Regiment which formed the garrison of Prague. In exchange, he handed over his old dragoon regiment to Peter de Buschiere; it was to continue under changing names until the end of Austria-Hungary in 1918.[3]

He was extremely active in developing the defences of Eger and Prague, in addition to overseeing the maintenance and development of fortifications throughout Bohemia as vice military commander. For Piccolomini's castle at Náchod, he drew up the fortification concept together with the military engineer Giovanni Pieroni.[14][4] After the entry of the imperial forces into the Northern War on the side of Poland against the Swedes in 1657, Croon was responsible for troop recruitment in Bohemia. In the same year, Melchior von Hatzfeldt asked for Croon to take command of the recently captured Kraków. However, the Viennese court refused because it considered Croon indispensable in Bohemia. In the war against the Turks in 1663–1664, he was responsible for the passage of German auxiliary troops into Hungary. In the last year of his life, he was promoted to field marshal lieutenant.[3] On 6 November 1665, Jan van der Croon died in Prague where he was buried in St. Thomas' Church.[13]

Properties

%252C_kostel_Nejsv%C4%9Bt%C4%9Bj%C5%A1%C3%AD_trojice.jpg.webp)

In 1651, Croon had acquired the village of Zahořany (today part of Křešice) and the surrounding villages of Horní and Dolní Týnec as well as Řepčice (today parts of Třebušín), besides Lovečkovice, Tašov, Řetouň (today part of Malečov), Valtířov (today part of Velké Březno) and other places. In 1663, he also bought Divice (today part of Vinařice) south of Louny. In Prague, he owned two houses in the Lesser Town, one on the site of today's Liechtenstein Palace on Kampa Island at the banks of the Vltava, the other on Malostranské náměstí, which was rebuilt by his heirs around 1700 to become today's Palais Kaiserstein.[13]

With his fortune, Croon funded the construction of the Holy Trinity Church in Zahořany, which was completed in 1657,[1] and the decoration of the Chapel of Mary Magdalene in the cloister of the Svatá Hora monastery and pilgrimage site.[13] In 1662, he donated the Baroque enclosure of the baptismal font in the Saint Martin church to his hometown. Until today, it bears his coat of arms.[1]

Reception and legend

His hometown of Weert still commemorates him and has the "Jan van der Croonstraat" named after him. From the middle of the 18th century onwards, he and his life were often mixed up or confused with Johann von Werth. Werth bears the same first name in Dutch (Jan van Werth) and his surname resembles Croon's birthplace. Contributing to the confusion may have been the fact that both came from closely neighbouring regions, Croon from Limburg, Werth from the Lower Rhine. Both also share a similar vita with the rise from simple origins to general and elevation to the Bohemian nobility. In Weert, also the legend arose that van der Croon had been viceroy ("onderkoning") of Bohemia, a position that did not exist at all, but to which his actually important post as vice military commander was falsely upgraded.[1]

The reappraisal of the confusion was mainly advanced by the 19th-century author Josef Habets.[15] Nevertheless, some legends continued to persist, such as the alleged title of "onderkoning", which Josef Habets saw as synonymous with the military command in Bohemia. Existing stories about Johann von Werth were even transferred to Jan van der Croon. In 1857, for example, the Dutch writer Emile Seipgens published a story about the shoemaker's servant Jan from Weert, who was once rejected by the beautiful woman Hanna as too poor. Returning to Weert as a general in 1635, Jan meets Hanna again, who recognises him and says to him "Ach, als ik dat had kunnen weten" ("Oh, if I had known"). This plot about Jan en Hanna was taken almost directly from the Cologne saga Jan un Griet to Johann von Werth and moved from Cologne to Weert.[1]

Family

Croon was married twice, first to Margaretha von Birnbach. After her death in 1663 he married Margaretha Blandina, née Söldner von Söldenhofen, the widow of his former regiment member Ernst von Schützen. Both marriages remained childless, and Croon adopted his younger brother Franz in 1662, appointing him as his heir. As the latter died only a few weeks after him, the inheritance passed to his only daughter Franziska Blandina van der Croon († 1701), who later married Helfried Franz von Kaiserstein and had three daughters with him. The eldest daughter Barbara married Leopold Wilhelm von Waldstein and brought Zahořany as a dowry into the marriage, but Leopold Wilhelm soon sold the manor in autumn 1703.[13][4]

His brother's wife, Maria Blandina, was the daughter of his own second wife Margarethe Blandina and thus became Jan's stepdaughter.[4] After Franz van der Croon's death, Maria Blandina married Hilfgott von Kuefstein, the brother-in-law of Johann von Werth. Werth had married Hilfgott's sister Susanna Maria in his third marriage. Susanna Maria later married in her fourth and last marriage Ernst Gottfried von Schütz und Leipoldsheim, a son of Margaretha Blandina and thus stepson of Jan van der Croon.[16] Ernst Gottfried also took over Werth's original lordship of Benatek from Werth's heirs.[17]

References

- Haanen 2000, pp. 243–256.

- Verzijl 1933, pp. 183–185.

- Haanen 2001, pp. 105–118.

- Crone 1922.

- Kleeberg 1893, pp. 6–7.

- Warlich 2012.

- Höbelt 2016, pp. 351–352.

- Höfer 1997, pp. 83–86.

- Höfer 1997, pp. 95–96.

- Höfer 1997, pp. 171–172.

- Heber 1847, p. 35.

- Höfer 1997, pp. 216–217.

- Zeman & Pátek 2017.

- Podlaha & Wirth 1912, p. 60.

- Habets 1862.

- Marek 2008.

- Meraviglia-Crivelli 1886, p. 169.

Sources

- Crone, G.C.E. (1922). "Stamboom Jan van der Croon" (PDF). Stichting Historisch Onderzoek Weert (in Dutch). Retrieved 2022-03-14.

- Haanen, Emile (2000). "Jan van der Croon" (PDF). De Maasgouw: Tijdschrift voor Limburgse Geschiedenis en Oudheidkunde (in Dutch). 119: 243–256. Retrieved 2022-03-14.

- Haanen, Emile (2001). "De militaire levensloop van Jan van der Croon" (PDF). Weert in woord en beeld : jaarboek voor Weert 2001 (in Dutch). Weert: Stichting Historisch Onderzoek Weert.

- Habets, Josef (1862). Jan Van Weert, en Jan Van Der Croon: eene bijdrage tot de geschiedenis van den dertigjarigen oorlog (in Dutch). Roermond: J.J. Romen.

- Heber, Franz Alexander (1847). Böhmens Burgen, Vesten und Bergschlösser (in German). Prague: Artistisch-Typographisches Institut.

- Höbelt, Lothar (2016). Von Nördlingen bis Jankau: Kaiserliche Strategie und Kriegsführung 1634-1645 (in German). Wien: Heeresgeschichtliches Museum. ISBN 978-3902551733.

- Höfer, Ernst (1997). Das Ende des Dreißigjährigen Krieges. Strategie und Kriegsbild (in German). Köln/Weimar/Wien: Böhlau. ISBN 978-3-412-04297-4.

- Kleeberg, Emilian (1893). K. u. k. Dragoner-Regiment Johannes Josef Fürst von Liechtenstein Nr.10, 1640-1893 (in German). Tarnopol: St. Kossowski.

- Marek, Miroslav (2008). "Kuefstein family". Genealogy.eu. Retrieved 2022-03-14.

- Meraviglia-Crivelli, Rudolf Johann von (1886). J. Siebmacher's grosses und allgemeines Wappenbuch Vierten Bandes, neunte Abteilung. Der Böhmische Adel (in German). Nürnberg: Bauer & Raspe.

- Podlaha, Anton; Wirth, Zdenek (1912). Topographie der historischen und Kunst-Denkmale im Königreiche Böhmen von der Urzeit bis zum Anfange des XIX. Jahrhunderts (in German). Vol. 35–36. Prague.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Verzijl, J. (1933). "Croon (Jan baron van der)". Nieuw Nederlandsch Biografisch Woordenboek (in Dutch). Vol. 9. Leiden: Sijthoff. pp. 183–185.

- Warlich, Bernd (2012). "Croon, Jan Freiherr van der". Der Dreißigjährige Krieg in Selbstzeugnissen, Chroniken und Berichten (in German). Retrieved 2022-03-14.

- Zeman, Václav; Pátek, Jakub (2017). "Zahořany a jejich držitelé ve stručné historické retrospektivě". Terra Sacra Incognita (in Czech). Retrieved 2022-03-14.