Jane Ingham

Rose Marie "Jane" Ingham (née Tupper‑Carey /ˌtˈʌpə ˈkɛəri/ ⓘ; 15 August 1897 – 10 September 1982) was an English botanist and scientific translator. She was appointed research assistant to Joseph Hubert Priestley in the Botany Department at the University of Leeds, and together, they were the first to separate cell walls from the root tip of broad beans. They analysed these cell walls and concluded that they contained protein. She carried out experiments on the cork layer of trees to study how cells function under a change of orientation and found profound differences in cell division and elongation in the epidermal layer of plants.

Jane Ingham | |

|---|---|

Ingham (left) with Albert Ingham (right) in 1966 | |

| Born | Rose Marie Tupper‑Carey 15 August 1897 Leeds, England |

| Died | 10 September 1982 (aged 85) Cambridge, England |

| Alma mater | University of Leeds (1928: MSc) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives | Michael Sadleir (brother-in-law) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions |

|

| Thesis | Geotropism or Gravity and Growth (1928) |

| Academic advisors | Joseph Hubert Priestley |

At Leeds, Ingham was appointed sub-warden of Weetwood Hall, and honorary secretary of the British-Italian League. In 1930, she joined the Imperial Bureau of Plant and Crop Genetics at the School of Agriculture in Cambridge, England, as a scientific officer and translator. The bureau was responsible for publishing a series of abstract journals on various aspects of crop breeding and genetics. In 1932, she married Albert Ingham, then a fellow and director of studies at King's College, Cambridge. Ingham spent the war years in Princeton, New Jersey, with her two sons, not wishing to return to England after travelling to the US just before the outbreak of World War II. In the last years of her life, she and her husband travelled extensively, and in 1982, she died at Cambridge.

Early life

Ingham was born on 15 August 1897, at Cromer House, Cromer Terrace, Leeds,[1] and baptised an Anglican in the Church of England at Donhead St Andrew, Wiltshire, on 14 September 1897.[2][lower-alpha 1] She was the youngest daughter of Helen Mary Tupper‑Carey, née Chapman, and Albert Darell.[7] They had married at Donhead St Andrew on 16 May 1890.[8] Helen Mary was the daughter of Reverend Horace Edward Chapman, a former rector of Donhead St Andrew,[9] and Adelaide Maria, née Fletcher.[7][lower-alpha 2]

Ingham's father was the son of the Reverend Tupper Carey and Helen Jane, née Sandeman.[10][11][lower-alpha 3] He was educated at Eton and Christ Church, Oxford, and trained at Cuddesdon Theological College. He was curate of Leeds before being appointed rector of St Margaret's Church, Lowestoft.[lower-alpha 4] In 1910, he was appointed canon residentiary of York, and later, became vicar of Huddersfield. From 1938, he was Chaplain to the King and at Monte Carlo.[10] Despite his given name being Albert Darell, he was known as "Tupper" to his friends and was described by John Gilbert Lockhart in Cosmo Gordon Lang's biography as follows:[14]

He could get at once on the easiest terms with every sort of person, from the 'drunks' of Leeds and Lowestoft to the millionaires of Monte Carlo ... Mercurial, overflowing with high spirits, irrepressible, he was everybody's friend and had a smile and a word for every passer-by in the streets of his parish.

Ingham had four siblings.[7] Her eldest sister, Jacqueline Marjorie, married the Reverend Edgar James Mitchell, and after their marriage, they undertook missionary work in the Far East.[15][lower-alpha 5] Ingham's elder sister, Edith, known as "Betty" to her friends and family,[17] married the author Michael Sadleir. Sadleir was the only son of Sir Michael Ernest Sadler, a former vice-chancellor of the University of Leeds.[18] Her elder brother, Humphrey Darell, was a tea planter in British East Africa before the outbreak of World War I. He was commissioned a lieutenant in the King's African Rifles, but was severely wounded in the right thigh during the East African campaign.[19] He married Marjorie Gertrude Drakes, née Bredin, the widow of Charles Henry Drakes.[20] In later life, he worked for the Colonial Service in Nigeria and was appointed a Companion of the Imperial Service Order in the Queen's 1959 Birthday Honours.[21][lower-alpha 6] Her younger brother, Peter Charles Sandeman, was a captain in the Royal Navy. He married Anne Ethel Violet Montagu Dundas, the eldest daughter of Robert Neville Dundas and Cecil Mary, née Lancaster.[23][24]

| Tupper-Carey family tree | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Education

Ingham was educated at Claire House School,[25] an all girl school in North Parade, Lowestoft, which specialised in the teaching of French.[26][lower-alpha 7] At the age of ten, she gained a prize in preliminary French examinations that were organised by the National Society of French Professors in England. She competed against candidates from the "best girls' schools in England",[27] the written tests consisting of translation and composition (prose and poetry), essay, and questions on 17th to 19th century French literature.[28] In the same year, she performed as Philaminte in the school's production of three scenes from Molière's Les Femmes Savantes.[25][lower-alpha 8]

Ingham showed an early interest in botany. In her youth, she would collect wildflowers to display at local parish shows.[30] Her grandmother, Helen Jane Carey, was a keen amateur botanist and specimen collector,[31] a popular and fashionable pastime in Victorian England.[32]: 29 In 1916, Ingham entered the University of Leeds to study botany and,[4] within three years, was a research student in the botany department at Leeds, studying water absorption at the growing point of plant roots.[33] In 1919, Ingham studied general zoology at the Citadel Hill Laboratory of the Marine Biological Association, Plymouth.[34] Annie Redman King, her friend from Weetwood Hall in Leeds,[35] was a Ray Lankester investigator at the laboratory.[34][lower-alpha 9]

Career

In January 1922, Ingham was appointed a research assistant in the botany department,[37] where Joseph Hubert Priestley was Dean of the Faculty of Science.[38] She and Priestley were the first to isolate cell walls from meristematic tissues in Vicia faba (broad beans). They analysed the walls for protein, cellulose, and pectin, and concluded that the walls contained protein.[39] They also studied when cellulose is first produced by plants,[37] the differences in shoot and root development,[40] and the role of the cork cambium.[41] These plant physiology studies were followed by two New Phytologist papers.[42] She later provided unpublished results from these experiments on broad bean embryos to the British botanist William Pearsall.[43] Described as a "brilliant scholar",[4] she was awarded a MSc degree on 28 June 1928, for her research work and thesis titled Geotropism or Gravity and Growth.[44]

In February 1930, Ingham joined the Imperial Bureau of Plant and Crop Genetics, at the Plant Breeding Institute, Cambridge,[45]: 140 as a translator and scientific officer.[46] Sir Rowland Biffen was the first director of the Cambridge bureau, and her supervisor, Penrhyn Stanley Hudson,[47] was deputy director.[45]: 140 [lower-alpha 10] She was fluent in French, Italian, German and Swedish,[4] and as a whole, the bureau had been capable of dealing with Spanish, Dutch, and Russian.[45]: 139 Abstracts were written on various aspects of plant breeding and genetics, with some of the foreign language papers requiring more complete translations. These abstracts were published in a quarterly journal called Plant Breeding Abstracts.[49] In 1931, she attended the eighth conference of the Association of Special Libraries and Information Bureaux (ASLIB) at Oxford,[50] where progress on ASLIB's newly-formed panel of expert translators was discussed.[51] After her marriage, she worked from home translating most of the German documents,[48] and in 1939, was put in charge of the bureau after Hudson fell ill.[52]

Personal life

Around 1922, Ingham sat for a portrait by William Roberts, the "English Cubist" artist. The finished painting was titled "Portrait of Miss Jane Tupper‑Carey" and was shown for the first time in November 1923 at New Chenil Galleries, Chelsea.[3] By 1926, she had been appointed sub-warden at Weetwood Hall, the then university hall of residence for women students.[53] In the same year, she was appointed the first honorary secretary of the Leeds branch of the British-Italian League. The League's aims were to found a chair in Italian at the University of Leeds and foster relations between the two countries.[54]

In the late 1920s, Ingham joined the Leeds University Amateurs, the university's amateur dramatics society, acting in several well-received roles, such as Sybil Bumont in The Watched Pot.[55] In December 1928, she took part in a fashion show of dresses through the ages at the Albion Hall, Leeds, in aid of St Faith's Homes. She wore a high-waisted, skin-tight coat of red cloth edged with fur, a long blue skirt trimmed with six rows of black velvet, and a feather toque. Her appearance was greeted with "shrieks of laughter" from the audience.[56]

They were ideally complementary, Jane as quick in thought and action as 'A. E.' was deliberate.

John Charles Burkill, Dictionary of National Biography (1981)

She married Albert Ingham on 6 July 1932 at St Edward's Church, Cambridge, in a private ceremony attended only by her parents, sister Edith, brother-in-law Michael Sadleir, who gave her away, and Redman King.[35] They had met after he had been appointed reader in mathematical analysis at the University of Leeds in 1926.[57][lower-alpha 11] Their engagement announcement in May 1932 had come as surprise to their circle of friends in Leeds, as there had been no indication that they were romantically involved. However, they had been quietly engaged with plans to announce it after lectures ended.[4][58]

In July 1939, Albert was awarded a Leverhulme Research Fellowship to study analytic number theory at the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) in Princeton, New Jersey.[59][60] At that point, they had two sons, Michael Frank and Stephen Darell,[lower-alpha 12] and the entire family sailed from Liverpool to New York on 1 September 1939.[61] However, just two days into their voyage, Britain declared war on Germany.[62] They were hesitant to bring their family back due to reports from Europe containing speculation of imminent total war.[63] Consequently, they made the decision to keep the family in Princeton, except for Albert, who had returned to England by 1942.[64] Alan Pars, godfather to their son Michael,[65] later recommended Albert for an Admiralty post in America knowing that Ingham and the children were still there.[64]

Later life and death

The Inghams owned a punt, called Pete, moored in the River Cam, and it was used regularly during the summer for trips and picnics.[66]: 127 They also went on many trips abroad, including India,[66]: 15, 128 and walking holidays in the French Alps.[57]: 563 It was on such a holiday that Albert died of a heart attack on a high path near Haute-Savoie, south-eastern France.[67] After his death, she resisted offers for her husband's mathematical notes and papers, instead keeping the papers in a cupboard at the house.[66]: 46

[She] was very wiry and fit ... [I have] an abiding memory of how fast and vigorously my grandmother would walk. She was always frustrated with my brother and I as we 'dawdled' fifty yards behind her. We just could not keep up with her furious pace.

— Dr Mark Ingham describing Jane Ingham, in Afterimages: Photographs as an External Autobiographical Memory System (2005), p. 46

Jane Ingham died at Cambridge on 10 September 1982,[5] and was cremated at the Cambridge City Crematorium, Huntingdon Road, Dry Drayton, on 20 September 1982.[68] Alan Pars, her friend and her husband's former colleague at Cambridge,[69] sent a wreath.[70]

Legacy

Discovery of protein in plant cell walls

Ingham and Priestley were the first to isolate cell walls from the middle lamella of the radicle and plumule meristems of Vicia faba.[71] They analysed the cell walls for protein, cellulose, and pectin. They noted that the cellulose walls of the radicle failed to react with iodine and sulphuric acid, or with chloriodide of zinc.[lower-alpha 13] They showed that the cellulose in the wall of the radicle is masked by other substances,[73] particularly proteins and fatty acids.[74] In the plumule, cellulose is associated with greater quantities of pectin, but less protein and fatty acid, particularly when the adult parenchyma is grown in light.[74]

They concluded that the meristematic cells had walls containing a protein‑pectin complex,[71]: 191 that is, these walls "... commencing as interfaces in a protein-containing medium may be regarded as composed at first mainly of protein."[75] Florence Mary Wood, a British postdoctoral researcher in biochemistry at Birkbeck College,[76] questioned their results and concluded that less than 0.001% of protein was found in the cell walls of the plants examined.[77]: 547, 569 Later researchers found protein in the cells but were unable to rule out the possibility of cytoplasmic contamination.[39] It is now known that the middle lamella consists of a pectic polysaccharide-rich material. However, the material properties and molecular organisation of the middle lamella are still not fully understood.[78]

Differences in cell division and elongation in the epidermal layer of plants

Ingham found that in the arch of the hypocotyl from sunflower seeds, Helianthus annuus, there are considerably more cells on the outside than on the inside. Counting from the beginning to the end of the arch, the result was "3,299 cells on the upper side as against 1,531 on the lower." This result means that the convex side of the arch leads the concave side, not only in terms of cell extension, but also in cell division behaviour, such that a different division rate would cause the growth difference. Consequently, the concave and convex sides show profound physiological differences.[79] The observation that in the hypocotyl the cells on the convex side are considerably larger than those on the inside could be explained by the uneven transverse transport of the growth hormone auxin. Auxin has a strengthening effect on the elongation growth of the cells. In the case of nutation phenomena, it is possible that curvature only occurs in a narrowly limited section of the shoot.[80]: 2

Harald Kaldewey, professor of botany at Saarland University in Saarbrücken, Germany,[81] measured the differences in the length of the sub-epidermal cells on the outer and inner periphery of the arch in the nutation curvature of the pedicels of snake's head fritillary, Fritillaria meleagris.[82] The result was expected if the curvature is based exclusively on differences in elongation growth. A difference in width between the sub-epidermal cells of the outer and inner periphery of the arch of curvature was not found. Sir Edward James Salisbury, the English botanist and ecologist,[83] found good agreement between the ratio of the epidermal cell lengths and the arch lengths of the nutation curvature of the epicotyl in seedlings of different woody plants. The findings of Ingham, Salisbury, and Kaldewey, do not necessarily contradict each other as the epidermis and sub-epidermal layer may well behave differently than cortical layers in terms of division and extension growth.[79]

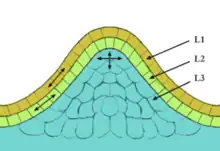

Importance of cell orientation in cork

.jpg.webp)

In Ingham's last study in the botany department at the University of Leeds, she ring-barked Laburnum and sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus) trees,[84] but left zigzag bridges of tissue with horizontal portions linking the bark above and below the cut.[41] At first, the lack of pressure within these bridges resulted in the formation of callus-like tissue, and the cambial initials, by repeated division, came to resemble ray cells. At a later stage, some of this mass of isodiametric (roughly spherical) cells became elongated horizontally in the direction of the bridge tissue.[85] Xylem and phloem formed in the horizontal portion of the bridge with its tracheary elements extended in a horizontal direction.[41] It has been postulated that calluses are formed because the cambium cells cannot function correctly under a change of orientation. For example, the altered direction of sap flow might affect the direction of cambial cell growth. Pressure, nutrient movements, and cambial basipetal auxin transport have also been suggested as causes.[84]

Publications

As author

- Priestley, Joseph Hubert; Tupper-Carey, Rose Marie (7 November 1922). "Physiological Studies in Plant Anatomy IV. The Water Relations of the Plant Growing Point". New Phytologist. London: Wheldon & Wesley. 21 (4): 210–229. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1922.tb07598.x. ISSN 0028-646X. JSTOR 2428025. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- Tupper-Carey, Rose Marie; Priestley, Joseph Hubert (2 July 1923). "The composition of the cell- wall at the apical meristem of stem and root". Proceedings of the Royal Society. Series B, Containing Papers of a Biological Character. London: Royal Society. 95 (665): 109–131. Bibcode:1923RSPSB..95..109T. doi:10.1098/rspb.1923.0026. ISSN 0950-1193. JSTOR 80874.

Communicated by Frederick Blackman. Received 25 April 1923.

Refereed by William Lawrence Balls in May 1923.[86] - Tupper-Carey, Rose Marie; Priestley, Joseph Hubert (23 July 1924). "The Cell Wall in the Radicle of Vicia faba and the Shape of the Meristematic Cells". New Phytologist. London: Wheldon & Wesley. 23 (3): 156–159. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1924.tb06630.x. ISSN 0028-646X. JSTOR 2427781. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- Tupper-Carey, Rose Marie (1928). Geotropism or Gravity and Growth (MSc). Leeds: University of Leeds. pp. 1–86. OCLC 1184171098. 30106005063069. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

Ingham's MSc thesis.

- Tupper-Carey, Rose Marie (1928). "The Development of the Hypocotyl of Helianthus annuus considered in connection with its Geotropic Curvatures". Proceedings of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society. Science Section Part 2. 1925 to 1929 Parts 5 to 10. Leeds: Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society. 1: 361–368. ISSN 0024-0281. OCLC 848524378.

Communicated by Joseph Hubert Priestley. Received 4 December 1928.

- Tupper-Carey, Rose Marie (1930). "Observations on the anatomical changes in tissue bridges across rings through the phloem of trees". Proceedings of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society. Science Section Part 2. December 1929 to May 1934. Leeds: Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society. 2: 86–94. ISSN 0024-0281. OCLC 848524378.

Communicated by Joseph Hubert Priestley. Received 26 February 1930.

As experimental collaborator

- Pearsall, William Harold; Ewing, James (1 March 1927). "The Absorption of Water by Plant Tissue in Relation to External Hydrogen-Ion Concentration" (PDF). The Journal of Experimental Biology. London. 4 (3): 245–257. doi:10.1242/jeb.4.3.245. ISSN 0022-0949. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 July 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

Ingham provided unpublished work on the swelling in buffer solutions of the air-dry, but living, embryos of broad bean seeds.

- Priestley, Joseph Hubert (31 July 1926). "Light and Growth II. On the Anatomy of Etiolated Plants". New Phytologist. London: Wheldon & Wesley. 25 (3): 145–170. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1926.tb06688.x. ISSN 0028-646X. JSTOR 2427687. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Priestley, Joseph Hubert; Swingle, Charles Fletcher (December 1929). Vegetative Propagation from the Standpoint of Plant Anatomy. Technical Bulletin 151. Washington: United States Department of Agriculture. pp. 1–98. hdl:2027/uiug.30112019336897. OCLC 784311303.

- Rhodes, Edgar; Woodman, Rowland Marcus (1925). "The Fatty Substances of the Plant Growing Point". Proceedings of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society. 1925 to 1929. Leeds: Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society. 1: 27–36. ISSN 0024-0281. OCLC 848524378.

Communicated by Professor Joseph Hubert Priestley. Received 21 October 1925.

See also

Footnotes

- A number of sources call her by the name "Jane", including the title of her portrait by William Roberts,[3] engagement announcement,[4] death notice in The Times,[5] and her husband's Royal Society memoir,[6]: 272 and in most instances, note she was born Rose Marie.

- Chapman was a son of banker David Barclay Chapman, who in 1875, purchased the advowson of St Andrew Donhead, and presented Horace Edward as the rector.[9]

- On 3 November 1887, Albert Darell Carey changed his surname by deed poll to Tupper‑Carey.[12]

- For a photograph of Albert Darell Tupper‑Carey taken at Lowestoft, see the photograph by Harry Jenkins at Lowestoft History.[13]

- Mitchell was rector of Donhead St Andrew from 1932 to 1952.[16]

- For more information on Humphrey Darell, and a photograph of him taken in British East Africa, see Europeans In East Africa.[22]

- At the school, Ingham was commonly known as "Marie".[25]

- Ingham's father was in the audience to see her performance, and after the play had finished, he addressed the audience in French.[25] Her mother was also fluent in French.[29]

- Redman King was warden at the hall when Ingham was a post-graduate research student.[36]

- Hudson ("Pen") was a remarkable linguist, who spoke most European languages fluently, including Russian and Ukrainian. His idea of a summer holiday was "to go to some distant place on a foreign freighter, practising the language, whatever it might be, with the crew."[48]

- Albert, whose hobby was mountaineering, flew from a holiday in Central Europe for the interview in Leeds.[4]

- In 1961, Michael was elected a Fellow of King's College, Cambridge, and later joined the staff of the University Observatory at Oxford.[6]: 273

- Cells that have cellulose in their walls are stained blue by chloriodide of zinc, or a solution of iodine followed by sulphuric acid.[72]: 77

References

- "Births". The Times. No. 35285. London. 18 August 1897. p. 1. ISSN 0140-0460. Gale CS17228050. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- "Baptisms at Donhead St Andrew. 1858 to 1922" (1897) [Baptism register]. Parish Records of Donhead St Andrew, Series: Registers, ID: 1732/5, p. 77. Chippenham: Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- Cleall, David; Davenport, Bob (2019). "English Cubist. William Roberts. Portrait of Miss Jane Tupper-Carey". www.englishcubist.co.uk. Tenby: William Roberts Society. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- Mather, Joyce (2 June 1932). "A Yorkshire Woman's Notes. A Later Development". Leeds Mercury. p. 8. OCLC 1016307518. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Deaths". The Times. No. 61338. London. 15 September 1982. p. 26. ISSN 0140-0460. Gale CS436701999. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- Burkill, John Charles (November 1968). "Albert Edward Ingham, 1900 to 1967". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. London: Royal Society. 14: 271–286. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1968.0012. ISSN 0080-4606. JSTOR 769447.

- Hesilrige, Arthur George Maynard, ed. (1903). "The Baronetage. Fletcher". Debrett's Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Companionage (190 ed.). London: Dean & Son. p. 232. OCLC 613690386. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- "Donhead St. Andrew. Marriage of Miss Helen Mary Chapman and the Rev. A. D. Tupper Carey". Western Gazette. Yeovil. 19 September 1890. p. 8. OCLC 14708041. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Harding, Timothy David (2015). Joseph Henry Blackburne: A Chess Biography. Jefferson: McFarland & Company. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-7864-7473-8. OCLC 900306725. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- "Obituary. Canon A. D. Carey". The Times. No. 49657. London. 22 September 1943. p. 8. ISSN 0140-0460. Gale CS135740726. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- Frecker, Paul (2021). "Miss Helen Sandeman (1831–1900) 15 January 1861". paulfrecker.com. London: Paul Frecker Fine Photographs. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- Phillimore, William Phillimore Watts; Fry, Edward Alex (1905). An index to Changes of name: Under authority of act of Parliament or Royal license, and including irregular changes from I George III to 64 Victoria, 1760 to 1901. London: Phillimore & Co. p. 322. OCLC 60736898. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- Jenkins, Harry (1910). "Reverend Albert Darell Tupper-Carey, Rector of St Margaret's, Lowestoft, 1901 to 1910". www.lowestofthistory.com. Arthur Taylor. Lowestoft: Lowestoft History. Archived from the original on 12 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- Lockhart, John Gilbert (1949). "6. Oxford". Cosmo Gordon Lang. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 35. OCLC 1244583479. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- "Miss Tupper-Carey and Mr. E. J. Mitchell". The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. Leeds. 23 April 1927. p. 16. OCLC 18793101. Retrieved 3 October 2021 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Ball, Duncan; Ball, Mandy (9 July 2020). "Rectors of The Church of St. Andrew, Donhead St. Andrew, Wiltshire". www.oodwooc.co.uk. Swindon: D & M Ball. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- "Noted Author's Home in the Cotswolds". Tatler. London. 19 April 1944. p. 81. ISSN 0263-7162. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "The Wedding of Mr. M. T. Sadler and Miss Edith Tupper Carey". The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. Leeds. 4 June 1914. p. 8. ISSN 0963-1496. OCLC 18793101. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "North Country Notes". Newcastle Journal. 4 October 1916. p. 4. ISSN 0307-3645. OCLC 926117601. Retrieved 3 October 2021 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Busy Cupid: Weddings and Engagements". Tatler. London. 22 March 1922. p. 48. ISSN 0263-7162. Retrieved 3 October 2021 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Imperial Service Order Companions". The London Gazette. No. 41727. 5 June 1959. p. 3724. OCLC 1013393168. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- Ayre, Peter J.; Ayre, Carolyn O. (2021). "Tupper‑Carey, Humphrey Darell (Capt.)". www.europeansineastafrica.co.uk. Wellington: Europeans In East Africa. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- "Wedding at St Mary's. Tupper Carey-Dundas". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. 8 July 1927. p. 8. ISSN 0307-5850. OCLC 624981792. Retrieved 3 October 2021 – via British Newspaper Archive.

-

"It's a Long Way to Tipperary. An Irish Story of the Great War. A to Z". longwaytotipperary.ul.ie. Limerick: Glucksman Library, University of Limerick. 2021. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

University of Limerick's World War I Online Exhibition.

- "Claire House School". Lowestoft Journal. 5 December 1908. p. 5. OCLC 900349662. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Claire House School for Girls, North Parade, Lowestoft". Eastern Daily Press. Norwich. 7 January 1910. p. 2. ISSN 0307-0956. OCLC 1063250029. Retrieved 12 October 2021 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Scholastic Successes". Lowestoft Journal. 25 July 1908. p. 5. OCLC 900349662. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "The Teaching of French". Boston Guardian. 7 March 1908. p. 5. OCLC 556439943. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Mrs. A. D. Tupper-Carey". The Times. No. 48051. London. 20 July 1938. p. 16. ISSN 0140-0460. Gale CS270217972. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- "Wild Flower Show at Lowestoft". Lowestoft Journal. 4 July 1908. p. 5. OCLC 900349662. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "An Important Discovery – Helen J. Tupper Carey, Ebbesborne Wake, Salisbury". Leeds Mercury. 13 August 1883. p. 8. OCLC 1016307518. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Shteir, Ann B. (1997). "Gender and 'Modern' Botany in Victorian England". Osiris. Women, Gender, and Science: New Directions. Chicago: History of Science Society. 12: 29–38. doi:10.1086/649265. ISSN 0369-7827. JSTOR 301897. PMID 11619778. S2CID 42561484.

-

"Botany" (PDF). Annual Report. 1919 to 1920. Leeds: University of Leeds. 16: 73. 1920. OCLC 499388156. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

Page 83 in the PDF.

- "Report of the Council. Occupation of Tables" (PDF). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. New series. Plymouth: Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 12 (2): 369. July 1920. ISSN 0025-3154. OCLC 1167043554. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- Mather, Joyce (3 August 1932). "The Tupper-Carey Wedding". Leeds Mercury. p. 6. OCLC 1016307518. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- King, Annie Redman. "King, Annie Redman 1911 to 1948" (1932) [Boxes]. Personalia, ID: LUA/PER/045. Leeds: University of Leeds. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

-

"Departmental Reports. Botany" (PDF). Annual Report. 1921 to 1922. Leeds: University of Leeds. 18: 94–95. 1922. OCLC 499388156. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

Pages 426 to 427 in the PDF.

-

"The Officers of the University" (PDF). Annual Report. 1921 to 1922. Leeds: University of Leeds. 18: 5. 1922. OCLC 499388156. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

Page 337 in the PDF.

- Lamport, Derek Thomas Anthony (1965). "The Protein Component of Primary Cell Walls. I. Introduction. B. Historical Perspective 1888 to 1959". In Preston, Reginald Dawson (ed.). Advances in Botanical Research. Vol. 2. London: Academic Press. p. 152. OCLC 879904706. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- Tupper-Carey & Priestley 1923, p. 129.

- "Societies and Academies. Leeds. Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society". Nature. London: Nature Portfolio. 125 (3155): 622. 19 April 1930. Bibcode:1930Natur.125..621.. doi:10.1038/125621a0. ISSN 1476-4687. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Priestley & Tupper-Carey 1922; Tupper-Carey & Priestley 1924.

- Pearsall & Ewing 1927, p. 252.

- "University News. Leeds, June 28". The Times. No. 44932. London. 29 June 1928. p. 18. ISSN 0140-0460. Gale CS302587613. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- Hudson, Penrhyn Stanley (May 1931). Ministry of Agriculture. "Imperial Bureau of Plant Genetics (for crops other than Herbage), Plant Breeding Institute, School of Agriculture, Downing Street, Cambridge, England". The Journal of the Ministry of Agriculture. Cambridge: HMSO. 38 (2): 138–142. OCLC 860139833. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- Diels, Ludwig; Merrill, Elmer Drew; Chipp, Thomas Ford; et al., eds. (1931). International Address Book of Botanists. Bentham Trustees. London: Baillière, Tindall & Cox. p. 204. OCLC 877383380. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- "Queen's Birthday Honours 1957. Officers of the Order of the British Empire (OBE). Civil Division". The London Gazette. No. 41089. 4 June 1957. p. 3380. OCLC 1013393168. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 July 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- Ellerton, Sydney (2020). "Chapter 9: Clouds Loom Over England" (PDF). Sugar Beet and World Travel. A Short Autobiography of Dr Sydney Ellerton 1914 to 2011 (Booklet). Kew: Shôn Ellerton. p. 70. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- Willis, John Christopher, ed. (September 1931). Empire Cotton Growing Corporation. "485. Plant-Breeding Abstracts". The Empire Cotton Growing Review. London: P. S. King & Son. 8 (3): 264. ISSN 0010-9819. OCLC 70734842. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- "List of Visitors". Report of Proceedings. 8th Conference. London: Association of Special Libraries and Information Bureaux. 8: 9. September 1931. OCLC 706048068.

- "A Key To Information. Value of Expert Translators". The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. Leeds. 26 September 1931. p. 8. OCLC 18793101. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Imperial Agricultural Bureaux Executive Council (1940). "C. The Bureaux — The Personnel". Annual Report. 1938 to 1939. London: HMSO. 10: 6. OCLC 950895993. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

-

"Halls of Residence for Women" (PDF). Annual Report. 1925 to 1926. Leeds: University of Leeds. 22: 57. 1926. OCLC 499388156. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

Page 226 in the PDF.

- "Letter to the Editor. The British-Italian League in Leeds". Leeds Mercury. 20 November 1926. p. 4. OCLC 1016307518. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Leeds University Amateurs". The Stage. London. 5 December 1929. p. 26. ISSN 0038-9099. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Mather, Joyce (7 December 1928). "Fashions Through the Ages. A Leeds Parade. Nothing New in Dresses To-day". Leeds Mercury. p. 3. OCLC 1016307518. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Burkill, John Charles (1981). "Ingham, Albert Edward". In Williams, Edgar Trevor; Nicholls, Christine Stephanie (eds.). Dictionary of National Biography 1961 to 1970. Vol. 8. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 562–563. ISBN 978-0198652076. OCLC 1038051360. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- "Forthcoming Marriages". The Times. No. 46146. London. 30 May 1932. p. 15. ISSN 0140-0460. Gale CS252651198. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- "Leverhulme Fellowships". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. 13 July 1939. p. 6. ISSN 0307-5850. OCLC 624981792. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Bulletin No. 9 (PDF) (Report). IAS Publications Collection. Princeton: Institute for Advanced Study. April 1940. p. 12. hdl:20.500.12111/5956. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 October 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- "S. S. Vandyck. Departed Liverpool 1 September 1939" (13 September 1939) [JPEG]. Book Indexes for New York Passenger Lists, Series: 1 January 1906 to 1 April 1942, ID: T715 157914759, p. 183. Washington: National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- "History of the BBC. Anniversaries. Chamberlain announces Britain is at war with Germany". BBC Online. London: BBC. 2021. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- Pars, Leopold Alexander. "Letter from A.E. Ingham at Berkeley, California" (1930) [Letter]. Papers of Leopold Alexander Pars, Series: Correspondence, ID: JCPP/Pars/1/1930. Cambridge: Jesus College. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- Pars, Leopold Alexander. "About a job that A.E. Ingham was offered in America" (1942) [Letter]. Papers of Leopold Alexander Pars, Series: 161 letters, ID: JCPP/Pars/1/1942. Cambridge: Jesus College. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- Pars, Leopold Alexander. "Letter from Pars's godson Michael Ingham and to him" (1980) [Letter]. Papers of Leopold Alexander Pars, Series: 235 letters, ID: JCPP/Pars/1/1973. Cambridge: Jesus College. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- Ingham, Mark (1 June 2005). Afterimages: Photographs as an External Autobiographical Memory System and a Contemporary Art Practice (PhD). Goldsmiths, University of London, Visual Arts Department [Fine Art]. London. OCLC 1006191005. 7465. Archived from the original on 21 August 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2021 – via PhilPapers.

- Burkill, John Charles (2004). "Ingham, Albert Edward (1900–1967), mathematician". Maths History St Andrews. Revised by Paul Cohn. St Andrews: Oxford University Press. 34099. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- Cambridge City Crematorium (20 September 1982). Cremation Register (Book). Cremations 1 to 104,953, dated 21 December 1938 to 28 June 1996. Girton: Cambridge City Council. Register Entry 635576. Retrieved 3 January 2022 – via Deceased Online.

- Pars, Leopold Alexander. "Death of Theodora Alberta Pars" (1980) [Letter]. Papers of Leopold Alexander Pars, Series: 218 letters, ID: JCPP/Pars/1/1980. Cambridge: Jesus College. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- Pars, Leopold Alexander. "Letter from Michael Ingham" (1982) [Letter]. Papers of Leopold Alexander Pars, Series: 146 letters, ID: JCPP/Pars/1/1982. Cambridge: Jesus College. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- McPherson, D. C. (23 October 1939). "Cortical Air Spaces in the Roots of Zea mays". New Phytologist. London: Cambridge University Press. 38 (3): 190–202. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1939.tb07098.x. ISSN 1469-8137. JSTOR 2428235. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- Sifton, Harold Boyd (29 February 1940). "Lysigenous Air Spaces in the Leaf of Labrador Tea, Ledum Groenlandicum Oeder". New Phytologist. London: Cambridge University Press. 39 (1): 75–79. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1940.tb07122.x. ISSN 1469-8137. JSTOR 2428866. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- Office of Experiment Stations (1924). "Recent Work in Agricultural Science. Agricultural Botany". Experiment Station Record. July to December 1924. Washington: Department of Agriculture. 51 (4): 330–331. ISSN 0097-689X. OCLC 869754915. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- "Societies and Academies. London. Royal Society". Nature. London: Nature Portfolio. 112 (2801): 26. 7 July 1923. Bibcode:1930Natur.125..621.. doi:10.1038/112026a0. ISSN 1476-4687. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Tupper-Carey & Priestley 1923, p. 110.

- Rayner-Canham, Marelene F.; Rayner-Canham, Geoffrey William (2008). "2. The Professional Societies. The Chemical Society. The Lesser-Known Initial Members". Chemistry Was Their Life: Pioneer British Women Chemists, 1880–1949. London: Imperial College Press. pp. 79–82. ISBN 978-1-86094-986-9. OCLC 768046657. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- Wood, Florence Mary (July 1926). "Further Investigations of the Chemical Nature of the Cell-membrane". Annals of Botany. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 40 (3): 547–570. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a090037. ISSN 0305-7364. JSTOR 43236554. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Zamil, Mohammad Shafayet; Geitmann, Anja (16 February 2017). "The middle lamella — more than a glue". Physical Biology. Bristol: IOP Publishing. 14 (1): 015004. Bibcode:2017PhBio..14a5004Z. doi:10.1088/1478-3975/aa5ba5. ISSN 1478-3975. PMID 28140367. S2CID 25394535.

- Halbsguth, Wilhelm (2020) [1965]. "3. Induktion von Dorsiventralität bei Pflanzen. 5. Krümmungen. e) Vergleich von Krümmungen und Dorsiventralität" [3. Induction of Dorsiventrality in Plants. 5. Curvatures. e) Comparison of Curvatures and Dorsiventrality]. In Ruhland, Wilhelm (ed.). Handbuch der Pflanzenphysiologie. Differenzierung und Entwicklung [Encyclopedia of Plant Physiology. Differentiation and Development]. Part III. Growth, Development, Movement (in German). Vol. 15/1. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. p. 370. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-36273-0_11. ISBN 978-3-662-36273-0. OCLC 913814739. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- Kunze, Henning (1977). "Nutation und Wachstum III" [Nutation and Growth III]. Elemente der Naturwissenschaft [Elements of Science] (in German). Goetheanum: Natural Science Section at the Goetheanum. 27: 1–11. doi:10.18756/EDN.27.1. OCLC 720264704. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- Edelbluth, Eckhardt; Kaldewey, Harald (January 1976). "Auxin in scapes, flower buds, flowers, and fruits of daffodil (Narcissus pseudonarcissus L.)". Planta. Bonn: Springer Science+Business Media. 131 (3): 285–291. doi:10.1007/BF00385428. ISSN 0032-0935. JSTOR 23372225. PMID 24424832. S2CID 6834483.

- Kaldewey, Harald (June 1957). "Wachstumsverlauf, Wuchsstoffbildung und Nutationsbewegungen von Fritillaria meleagris L. im Laufe der Vegetationsperiode" [Growth Pattern, Growth Substance Formation and Nutation Movements of Fritillaria meleagris L. in the Course of the Vegetation Period]. Planta (in German). Bonn: Springer Science+Business Media. 49 (3): 300–344. doi:10.1007/BF01911291. ISSN 1432-2048. JSTOR 23363315. S2CID 41817628.

- Clapham, Arthur Roy (November 1980). "Edward James Salisbury. 16 April 1886 to 10 November 1978". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. London: Royal Society. 26: 502–526. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1980.0014. ISSN 0080-4606. JSTOR 769791.

- Sinnott, Edmund Ware (1960). "Part Two. The Phenomena of Morphogenesis. 6. Polarity". Plant Morphogenesis. McGraw-Hill publications in the botanical sciences. Vol. 2. New York: Academic Press. pp. 128–129. hdl:2027/uc1.b3741908. OCLC 325141.

- Philipson, William Raymond; Ward, Josephine Margaret; Butterfield, Brian Geoffrey (1971). "10. Experimental Control of Cambial Development". The Vascular Cambium: Its development and activity. London: Chapman & Hall. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-412-10400-8. OCLC 144649. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- Balls, William Lawrence. "Referee's report on 'The composition of the cell-wall at the apical meristem of stem and root' by R. M. Tupper-Carey and J. H. Priestley" (May 1923) [Item]. Referees' reports on scientific papers submitted to the Royal Society for publication, Series: Referees' reports: volume 29, peer reviews of scientific papers submitted to the Royal Society for publication, ID: RR/29/62, pp. 1–4. London: Royal Society. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

Further reading

- Blight, Denis; Ibbotson, Ruth (2011). Hemming, David (ed.). CABI: a century of scientific endeavour (PDF). CABI International. Malta: Gutenberg Press. ISBN 978-1-84593-873-4. OCLC 1040280202. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Ede, Ronald, ed. (1930). "Members of Staff at the School of Agriculture, Downing Street, Cambridge". Cambridge University Agricultural Society Magazine. Vol. 3. Cambridge University Agricultural Society. Cambridge: W. Heffer & Sons. p. 74. OCLC 43472660.

Penrhyn Stanley Hudson and Ingham are photographed seated together, on the left, at the front.

- Lang, Cosmo Gordon (1945). Tupper (Canon A. D. Tupper-Carey): A Memoir of a Very Human Parish Priest. London: Constable & Co. OCLC 931231033. Archbishop Cosmo Lang's biography of Ingham's father.

- Priestley, Joseph Hubert; Scott, Lorna Iris; Harrison, Edith (1964) [First published in 1938]. An Introduction to Botany, with special reference to the structure of the flowering plant. Illustrated by Marjorie Edith Malins and Lorna Iris Scott. London: Longmans Green & Co. OCLC 1150024139. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

External links

- Portrait of Ingham by William Roberts, circa 1922, "An English Cubist".

- Afterimages: Photographs as an External Autobiographical Memory System and a Contemporary Art Practice, University of the Arts London Research Online. Photographs of Jane Ingham, taken by Albert Ingham, for Mark Ingham's PhD thesis at Goldsmiths, University of London.

- Works by Ingham at WorldCat.

- Lorna Scott and her Mortar Board by Margaret Stewart, for Egham Museum, on botanist Lorna Iris Scott, Joseph Hubert Priestley's collaborator after Ingham left for Cambridge.