Jean Jules Jusserand

Jean Adrien Antoine Jules Jusserand (18 February 1855 – 18 July 1932) was a French author and diplomat. He was the French Ambassador to the United States 1903-1925 and played a major diplomatic role during World War I.[2]

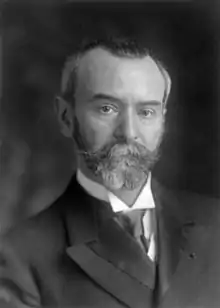

Jean Adrien Antoine Jules Jusserand | |

|---|---|

J. J. Jusserand in 1910 | |

| French Ambassador to the United States | |

| In office 1902–1924 | |

| Preceded by | Jules Cambon[1] |

| Succeeded by | Émile Daeschner[1] |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Jean Adrien Antoine Jules Jusserand 18 February 1855 Lyon, France |

| Died | 18 July 1932 (aged 77) Paris, France |

| Spouse | Elisa Richards |

| Parent(s) | Jean Jusserand and Marie Adrienne Tissot |

| Alma mater | University of Lyon |

Birth and education

Born into a rich Lyonnais family, Jean Jules Jusserand spent his childhood between his familial residence in Saint-Haon-le-Châtel and Chalon's boarding school in Lyon. After his father's death in 1870, he was determined to honour him by learning new cultures and excelling in his international and bicultural career.[3]

After his scholarship in Chartreux, he continued his studies at the University of Lyon, not knowing where these studies would lead him. He also wanted to increase his knowledge, which he judged insufficient. He studied literature, science, law and history, where he became an excellent student in all the subjects. He received two licenses, history and law, and, despite the worries his family had about him not completing his studies, he obtained a doctorate in history. Jusserand continued travelling across the world, learning languages and discovering new horizons. He completed his studies in 1875 and pursued an international career.[3]

Career

His career started in 1878 when he applied to the Foreign Affairs national competition, at the age of 23. He first started as a student-consul, and he was then kept as a help-consul in London under the direction of Mr. Langlet, who congratulated him on his remarkable work. In 1880, he became sous-chef of the 'cabinet de Barthélemy-Saint-Hilaire', where he worked as minister of foreign affairs. His literary work enabled him to reach a higher status as Paul Cambon's partner, the Minister of France in Tunisia, in 1882. During this time Jusserand was in charge of the administrative organisation of the protectorate. He became known as a respected diplomat, thanks to his contributions to the great humanization of the protectorate. Jusserand came back to the Quai d’Orsay In 1887, in a delicate moment, where he worked in the political sector. In 1898 he exercised in the role of emissary near Saint-Siège, then Minister of France in Copenhagen. In 1902 Jusserand was named Ambassador to the United States, under the presidency of Loubet.[3]

Ambassador in Washington

Before the war

As the new French ambassador in Washington, Jean Jules Jusserand succeeded Jules Cambon who, in Madrid, was replacing his brother Paul Cambon, himself nominated in London. Jusserand took up his position on 7 February 1903.

In 1911, he was admitted as an Honorary Member of the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of New Jersey.[4]

He soon won Roosevelt's sympathy, in addition to the President's successors'. Thus, during 22 years, Jusserand was the French politic spokesperson alongside 5 presidents of the United States (Roosevelt, Taft, Wilson, Harding and Coolidge), especially he had served as Dean of the Diplomatic Corps from May 1913 to January 1925.[5]

As in June 1905, the French and German concurrence over Morocco's domination nearly lead to a war. Jusserand used his influence on Roosevelt in order to play an efficient role in the Algeciras Conference. The support that was brought by the United States and the United Kingdom to France helped the French access to the Cherifian Empire (known today as the Moroccan Empire.). Everything happened in a very friendly and courteous manner, several American and French personalities considered that the ambassador had "saved the peace".

During the war

Jean Jules Jusserand played an important role in the United States's entry into the war. As early as 1914, he campaigned for the entry of the United States to support France. It was a period of anguish and concern for Jusserand because the American public's opinion was very divided. It took the Americans more than three years to enter the war, being triggered by the submarine campaign launched by Germany.

On 12 March 1917, the House of Representatives authorised the arming of commercial vessels. Following the attack on two US ships by German U-boats, the US president realised on 20 March that the US was in fact at war with Germany. The United States would not be able to limit its intervention to the naval domain alone. On 2 April, he announced to Congress that he wished to go to war alongside the Entente, sending troops on French soil, thus directly entering the conflict. The US Senate approved this resolution by 82 votes to 6. On 6 April 1917, the US was officially at war. On 28 June 1917, the first American division landed at Saint-Nazaire. Jean Jules Jusserand said on this occasion: "For the first time, a neutral nation has decided to enter the conflict without prior bargaining, without having laid down a condition."

On 10 May 1917, French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau sent him a telegram to congratulate him on his action, saying "All you have said is excellent." On 5 September, the United States of America participated in their first offensive against Germany. On 11 November, during an allied offensive, the armistice was signed, thus ending the First World War.

He helped to support of professor Thomas Garrigue Masaryk legions especially in Russia and in negotiation for independent Czechoslovak state in America from May to October 1918.[6]

For the Versailles negotiations, President Wilson was accompanied in France by Jean Jules Jusserand, whom he trusted. As a matter of fact, Wilson was the first incumbent US president to come to Europe. The Paris Peace Conference, beginning on 18 January 1919, culminated in the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June, establishing a seemingly definitive peace.

After a brief period of harmony lasting only 22 years, another world conflict ensued in 1939. However, Jusserand had no influence on this Second world war, passing away in 1932.

After the war

.jpg.webp)

Even after the First World War, Jean Jules Jusserand was still fighting to maintain the peace obtained after so many efforts and sacrifices. He accompanied the American President Woodrow Wilson to the Paris Peace Conference (1919), during which was signed the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June 1919. When the Polish army invaded Ukraine, a Russian counter-attack reached Warsaw, where there was a rise in revolutionary ideas. France sent Jusserand at the head of a diplomatic and military mission to save the Polish.

He remained the French ambassador to Washington for the next five years under presidents Warren G Harding and Calvin Coolidge. During this time, he published a dozen books in French and English, on various subjects. Later on he returned to France, where he spent some time with his wife in Saint-Haon-le-Châtel, their property in Forez.

In 1923, Jean Jules Jusserand presided and delivered a speech during the inauguration ceremony for the American war memorial.

At the age of seventy, he retired. Émile Daeschner succeeded him in 1924, followed by Henry Bérenger on 1 January 1925.

On 10 January 1925, a farewell banquet was organised in his honour by the American government in order to express their esteem and gratitude. This ceremony brought together the most important political, scientific and cultural figures of the United States. He was also awarded a medal for his deeds.

In 1930, Jean Jules Jusserand published his last book, The evolution of the American sentiment during the war (L'évolution du sentiment américain pendant la guerre).

He died in 1932 in Paris at the age of 77, following a lengthy bout of kidney disease.[2] His national funeral took place in Notre-Dame, and his body rests in the family home in Saint-Haon-le-Châtel.

Alliance Française

.jpg.webp)

In 1884, Jean Jules Jusserand took part in the foundation of the Alliance Française. The Alliance Française is a French organisation which aims to promote French culture and language, especially after France's defeat by Germany in 1870.

This association is not subject to any political or religious influence.

The Fondation de l’Alliance Française is the "moral and juridic reference" for the other Alliances Françaises. It is she whom approves the formation of new Alliances françaises by approving their status. It helps the Alliances to form employees, and guide them in the extension of their activities or even when they go through tough times.

The Alliance Française has buildings all around the world and is today the biggest cultural Non-Governmental Organisation of the world with around 1000 establishments in more than 136 countries. The Alliance Française in Lyon was created in 1984 and has received many Labels since then. Nowadays, it is the first French language school in Lyon and the third Alliance Française in France. Within it, there is a multicultural team of 40 people, who welcome 2500 students per year and more than 130 nationalities. The 2,500 m2 of modern locals dedicated to the study and learning of languages with 17 classrooms. It perpetuates the founders' spirit, including Jusserand's.

Legacy

Even today, different monuments exist in France and the United States in order to commemorate Jusserand's diplomatic role.

A pink granite bench in Rock Creek Park honoring Jusserand was dedicated by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt on 7 November 1936. It is the first memorial erected on Federal property to a foreign diplomat.[7] In 2014 Washington City Paper called it the "best obscure memorial" in D.C.[8]

Literary work

He wrote a series of articles published in Cosmopolis: An International Monthly Review on the history of French reactions to Shakespeare.[9] Jusserand was a close student of English literature who produced some lucid and vivacious books on comparatively little-known subjects:

His publications in French

- Le Théâtre en Angleterre, depuis la conquête jusqu'aux prédécesseurs immédiats de Shakespeare (1878)

- Les Anglais au Moyen Âge: la vie nomade et les routes d'Angleterre au XIVe siècle (1884; Eng. trans., English Wayfaring Life in the Middle Ages, by LT Smith, 1889)

- Le Roman au temps de Shakespeare (1887) (The English Novel in the Time of Shakespeare, (1887), translated from French by Elizabeth Lee)

- Histoire littéraire du peuple anglais (vol. 1, 1893; vol. 2, 1904; vol. 3, 1909; Eng. trans., A Literary History of the English People, by G.P. Putnam, 1914).

- L'Épopée de Langland (1893; Eng. trans., Piers Plowman, 1894).

- Les Anglais au Moyen Âge. L'Épopée mystique de William Langland (1893) (Piers Plowman, a contribution to the history of English mysticism, (1894), translated from the French by Marion and Elise Richards, revised and enlarged by the author)

- Le Roman d'un roi d'Écosse, (1895), (The Romance of a King's life,(1896), translated from French by Marion Richards, revised and enlarged by the author)

- Histoire abrégée de la littérature anglaise (1896) Online text

- Shakespeare en France sous l'ancien régime (1898) Online text

- Les Sports et jeux d'exercice dans l'ancienne France (1901)

- Ronsard (1913) Online text

- Recueil des instructions données aux ambassadeurs et ministres de France depuis les traités de Westphalie jusqu'à la Révolution française. XXIV-XXV, Angleterre, publié sous les auspices de la commission des archives diplomatiques au ministère des affaires étrangères, avec une introduction et des notes par J. J. Jusserand (1929)

His publications in English

- A French Ambassador at the Court of Charles II (1892), from the unpublished papers of the count de Cominges. Online text

- English essays from a French pen (1895) Online text

- A Literary history of the English people from the origins to the Renaissance (1895)

- A Literary history of the English people from the Renaissance to the Civil War (1906)[10]

- Piers Plowman, the work of one or of five (1909) Online text

- "What to Expect of Shakespeare". Proceedings of the British Academy, 1911–1912. 5: 223–244. First Annual Shakespeare Lecture of the British Academy (1911)

- With Americans of Past and Present Days (1916),[11] for which he earned the first Pulitzer Prize for History.

- The School for ambassadors and other essays (1925) Online text

- The evolution of the American sentiment during the war (1930)

- What Me Befell : The Reminiscences of J. J. Jusserand (1933).

Participation in other works

- Jean-Jules Jusserand, "La Tunisie", an extract from La France coloniale, histoire, géographie, commerce, ouvrage published under M. Alfred Rambaud. Paris : A. Colin (1888)

- Jean-Jules Jusserand, « Les Grands Écrivains Français. Études sur la vie, les œuvres et l’influence des principaux auteurs de notre littérature », text inserted in Jules Simon, Victor Cousin, Paris, Hachette, 1887

Letters

- Jean-Jules Jusserand, [Letter to Anatole France], 9 March 1888 or 1889, Correspondence d’Anatole France, Bibliothèque Nationale

- Jean-Jules Jusserand, [Letters to Ferdinand Brunetière], 11 and 23 March, 23 September, Correspondance de Ferdinand Brunetière, Bibliothèque Nationale (Nouvelles Acquisitions Françaises, 25 041/307, 309, 313).

- Jean-Jules Jusserand, [Letter to Gaston Paris], 11 September 1900, Correspondance de Gaston Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale

- Jean-Jules Jusserand, [Letter to Joseph Reinach], 23 November 1898, Correspondance de Joseph Reinach, Bibliothèque Nationale

- Jean-Jules Jusserand, [Letter to Arvède Barine], 12 February 1889, Correspondence d’Arvède Barine, Bibliothèque Nationale

See also

References

- "Ambassadeurs de France aux Etats-Unis depuis 1893 - France in the United States". Embassy of France in Washington, D.C. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- "Jules Jusserand Expires. Was French Ambassador". Free Lance-Star. Associated Press. 18 July 1932. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

Jean J. Jusserand, former French ambassador to the United States, died at 8 o'clock this morning. ... Death came peacefully as he lay ill in his Paris home.

- H. Cogoluenhe (December 1988). "Un lyonnais injustement oublié : Jules Jusserand". La Revue Rive Gauche (in French). p. 3.

- "Jean-Adrien-Antoine-Jules Jusserand | The Society of the Cincinnati in the State of New Jersey". njcincinnati.org. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- "Deans of the Diplomatic Corps". Bureau of Public Affairs, U.S. Department of State. 1 March 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- Preclík, Vratislav. Masaryk a legie (Masaryk and legions), váz. kniha, 219 str., vydalo nakladatelství Paris Karviná, Žižkova 2379 (734 01 Karvina, CZ) ve spolupráci s Masarykovým demokratickým hnutím (Masaryk Democratic Movement, Prague), 2019, ISBN 978-80-87173-47-3, pages 87, 92, 124–128, 140–148, 167, 184–190.

- "Rock Creek Park: Monuments, Statues and Memorials". National Park Service. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- Michael E. Grass (2014). "Best Obscure Memorial: Jules Jusserand Memorial". Washington City Paper. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- "Shakespeare in France". The Dial. 22 (256): 105–107. 16 February 1897.

- Matthews, Brander (1907). "Review of A Literary History of the English People, Vol. I, Part I, From the Renaissance to the Civil War by J. J. Jusserand". North American Review. 184: 759–763.

- Jusserand, Jean Jules (1916). With Americans of Past and Present Days. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

Further reading

- Greenhalgh, Elizabeth. "The Viviani-Joffre Mission to the United States, April–May 1917: A Reassessment." French Historical Studies 35.4 (2012): 627–659.

- Haglund, David G. "Theodore Roosevelt and the "Special Relationship" with France." in A Companion to Theodore Roosevelt (2011): pp 329–349.

- Young, Robert. An American by Degrees: The Extraordinary Lives of French Ambassador Jules Jusserand (McGill-Queen's University Press, 2009). excerpt, A standard scholarly biography

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Jusserand, Jean Adrien Antoine Jules". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 593.