Jean Miélot

Jean Miélot, also Jehan, (born Gueschard, Picardy, died 1472) was an author, translator, manuscript illuminator, scribe and priest, who served as secretary to Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy from 1449 to Philip's death in 1467, and then to his son Charles the Bold.[1] He also served as chaplain to Louis of Luxembourg, Count of St. Pol from 1468, after Philip's death.[2] He was mainly employed in the production of de luxe illuminated manuscripts for Philip's library. He translated many works, both religious and secular, from Latin or Italian into French, as well as writing or compiling books himself, and composing verse. Between his own writings and his translations he produced some twenty-two works whilst working for Philip,[3] which were widely disseminated, many being given printed editions in the years after his death, and influenced the development of French prose style.

Career

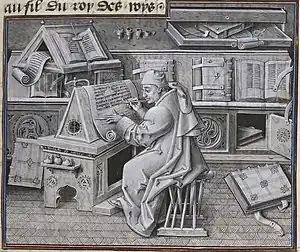

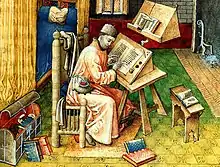

Little is known of his early career. He was born at Gueschard, between Abbeville and Hesdin, in what is now the Somme department, but was then in Picardy, and from 1435 part of the Duchy of Burgundy.[4] He was recruited by the Duke after he translated and adapted the Speculum Humanae Salvationis into French in 1448, and as well as his court salary he was made a canon of Saint Peter's in Lille in 1453, serving until his death in 1472, when he was buried in the church. He was probably not usually resident.[5] As a priest and as an employee of the court he would have been exempt from guild regulations, which was probably an advantage to his career.[6] He seems to have had lodgings in the palace, which are perhaps realistically shown in a miniature in Brussels,[7] and also to have run a workshop of scribes in Lille. After the Feast of the Pheasant in 1454, an enthusiasm in the Court to revive the Crusades led to commissions to translate travel books about the Middle East.

Because of the particular Burgundian fashion for presentation miniatures, where the author is shown presenting the book (in which the miniature itself is contained) to the Duke or another patron, we have an unusually large number of portraits of Miélot for a non-royal person of the period, which mostly show consistent facial features - he would have been very well known to the artists, and may well have had influence in allocating commissions to them. These are in books he wrote - in both senses of the word, as he usually scribed Philip's copy himself.[8]

Philip the Good was the leading bibliophile of Northern Europe, and employed a number of scribes, copyists and artists, with Miélot holding a leading position among the former groups (see also David Aubert). His translations were first produced in draft form, called a "minute", with sketches of the images and illuminated letters. If this was approved by the Duke, after being examined and read aloud at court, then the final de luxe manuscript for the Duke's library would be produced on fine vellum, and with the sketches worked up by specialist artists. Miélot's minute for his Le Miroir de l'Humaine Salvation survives in the Bibliothèque Royale Albert I in Brussels, which includes two self-portraits of him richly dressed as a layman.[9] The presentation portrait to La controverse de noblesse, a year later, shows him with a clerical tonsure.[10] His illustrations are well composed, but not executed up to the standard of manuscripts for the court. His text, on the other hand, is usually in a very fine Burgundian bastarda blackletter script, and paleographers can recognise his hand.

Works

A fuller list, in French, with partial details of surviving manuscripts and a bibliography, is on-line at Arlima.

Translations

- Cicero's letter to his brother on the duties of a governor - Philip presented this to his son Charles the Rash

- Romuléon of Benevento da Imola, a history of Ancient Rome,[12] surviving in six copies. Like other works below, this addressed issues of the correct conduct of rulers of great interest to the inner court circle.[13] Philip the Good's copy was scribed by Colard Mansion, who was shortly to become the first printer of books in French.

- Vie et miracles de Saint Joss

- La controverse de noblesse, a translation of De nobilitate (1429) by Buonaccorso da Montemagno (Buonaccorso da Pistoia), a precursor of Castiglione's Il Cortegiano, together with:

- Le Débat d'honneur from the Italian of Giovanni Aurispa, a version of "Comparatio Hannibalis, Scipionis et Alexandri, Lucian's Twelfth Dialogue of the Dead. Both works survive in fourteen manuscript copies, and were printed together in about 1475 by Colard Mansion in Bruges.[14]

- Traité sur l'Oraison Dominicale

- Miroir de l'âme pécheresse, a translation of the Speculum aureum animae peccatricis.

- Les quattres choses derrenieres, translation of Cordiale quattuor novissimorum, later printed in Bruges by William Caxton and Colard Mansion in about 1475. Caxton later printed an English translation from Miélot's French by Anthony Woodville, Earl Rivers.

- Advis directif pour faire le passage doultre-mer, a translation of the Directorium ad faciendum passagium transmarinum, a Latin treatise on recovering the Holy Land through crusading

- La Vie de sainte Catherine d'Alexandrie, later printed. The only two illuminated copies known are Philip's (BnF) and one illuminated by Simon Marmion for Margaret of York.[15]

- Secret des secrets, by the Pseudo-Aristotle, supposedly advice given by Aristotle to Alexander the Great, originally an Arabic text, translated into Latin by Philip of Tripoli in the 13th century.[16]

Own works

Mostly copies, compilations or adaptations relying heavily on other writers.

- Le Miroir de l'Humaine Salvation, one of four French versions of the Speculum Humanae Salvationis[17]

- Miracles de Nostre Dame an important compilation.

- A version of the Epître d'Othéa by Christine de Pisan, augmented with material from the Genealogia Deorum Gentilium of Boccaccio.

- His commonplace book or workbook survives in the BnF (Ms. fr. 17001, apparently not originally bound up together), containing draft translations and drawings and initials, as well as verses, including some written for court occasions. They are more of more historical than literary interest. There is a "labyrinth" design containing the letters of MIELOT.[18]

Notes

- Sometimes spelled "Miellot" in the 18th and 19th centuries.

- Wilson & Wilson, p.59

- Catholic Encyclopedia

- It was ceded in the 1435 Treaty of Arras. Gueschard was a commune in 1854, but now appears to have been swallowed up by Abbeville.

- Wilson & Wilson, p.59, though Arlima (external link) say he was made a canon in 1452.

- T Kren & S McKendrick, 19

- below and Brussels Royal Library, MS 9278, fol. 10r Archived 2008-06-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Two further images of Miélot are shown here

- Wilson & Wilson, pp.50-60. Self-portraits pp. 51 and 56

- The Frontispiece to the Chroniques de Hainaut: An Introduction to Valois Burgundy drawing, near bottom

- For full image see Brussels link below.

- Craig Kallendorf, A Companion to the Classical Tradition, p. 24, 2007, Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 1-4051-2294-3

- Humanism and Good Governance, article by Christine Raynaud, in Fifteenth-century Studies, 1998

- Princes and Princely Culture, 1450-1650, pp.75-77 Arjo Vanderjagt, 2003, Brill

- T Kren & S McKendrick, 116 and 182

- T Kren & S McKendrick, 245

- MS in Glasgow and Illuminated copy, with presentation miniature

- Wilson & Wilson, pp. 66-71

References

- T Kren & S McKendrick (eds), Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe, Getty Museum/Royal Academy of Arts, 2003, ISBN 1-903973-28-7

- Wilson, Adrian, and Joyce Lancaster Wilson. A Medieval Mirror. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

External links

- Modern recreation of Miélot's "scribal station", as shown in the Brussels portrait.

- Jean Miélot at Waddesdon Manor