Elizabeth of Bosnia

Elizabeth of Bosnia (Serbo-Croatian: Elizabeta Kotromanić/Елизабета Котроманић; Bosnian: Elizabeta Bošnjačka; Hungarian: Kotromanics Erzsébet; Polish: Elżbieta Bośniaczka; c. 1339 – January 1387) was queen consort of Hungary and Croatia, as well as queen consort of Poland, and, after becoming widowed, the regent of Hungary and Croatia between 1382 and 1385 and in 1386.

| Elizabeth of Bosnia | |

|---|---|

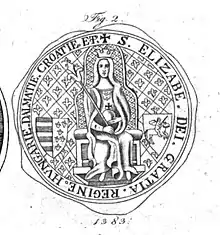

Seal of Elizabeth, naming her "by the grace of God queen of Hungary, Dalmatia, and Croatia" | |

| Queen consort of Hungary and Croatia | |

| Tenure | 20 June 1353 – 10 September 1382 |

| Queen consort of Poland | |

| Tenure | 5 November 1370 – 10 September 1382 |

| Born | c. 1339 |

| Died | January 1387 Novigrad Castle, Novigrad, Kingdom of Croatia |

| Burial | Székesfehérvár Basilica, Hungary (previously St Chrysogonus's Church, Croatia) |

| Spouse | Louis I, King of Hungary and Poland |

| Issue Details | |

| House | Kotromanić |

| Father | Stephen II, Ban of Bosnia |

| Mother | Elizabeth of Kuyavia |

Daughter of Ban Stephen II of Bosnia, Elizabeth became Queen of Hungary upon marrying King Louis I the Great in 1353. In 1370, she gave birth to a long-anticipated heir, Catherine, and became Queen of Poland when Louis ascended the Polish throne. The royal couple had two more daughters, Mary and Hedwig, but Catherine died in 1378. Initially a consort with no substantial influence, Elizabeth then started surrounding herself with noblemen loyal to her, led by her favourite, Nicholas I Garai. When Louis died in 1382, Mary succeeded him with Elizabeth as regent. Unable to preserve the personal union of Hungary and Poland, Elizabeth secured the Polish throne for her youngest daughter, Hedwig.

During her regency in Hungary, Elizabeth faced several rebellions led by John Horvat and John of Palisna, who attempted to take advantage of Mary's insecure reign. In 1385, they invited King Charles III of Naples to depose Mary and assume the crown. Elizabeth responded by having Charles murdered within two months of his coronation, in February 1386. She had the crown restored to her daughter and established herself as regent once more, only to be captured, imprisoned and ultimately strangled by her enemies. Her daughter remained on the throne.

Descent and early years

Born about 1339, Elizabeth was the daughter of Ban Stephen II of Bosnia, the head of the House of Kotromanić.[1] Her mother, Elizabeth of Kuyavia, was a member of the House of Piast[2] and grandniece of King Władysław I of Poland.[3] The Hungarian queen dowager Elizabeth was a first cousin once removed of Elizabeth's mother. After her daughter-in-law Margaret succumbed to the Black Death in 1349,[4] Queen Elizabeth expressed interest in her young kinswoman, having in mind a future match for her widowed and childless son King Louis I of Hungary. She insisted on immediately bringing the girl to her court in Visegrád for fostering. Despite her father's initial reluctance, Elizabeth was sent to the queen dowager's court.[5]

In 1350, Tsar Stephen Uroš IV Dušan of Serbia attacked Bosnia in order to regain Zachlumia. The invasion was not successful, and the tsar tried to negotiate peace, which would be sealed by arranging Elizabeth's marriage to his son and heir apparent, Stephen Uroš V. Mavro Orbini, whose reliability in this regard "is a subject of controversy", wrote that the tsar expected Zachlumia to be ceded as Elizabeth's dowry, which her father refused.[6] Later that year she was formally betrothed to the 24-year-old Louis,[7] who hoped to counter Dušan's expansionist policy either with her father's help or as his eventual successor.[8]

Marriage

Elizabeth's marriage to Louis was celebrated in Buda on 20 June 1353.[9] The couple were related within the prohibited degree of kinship, Duke Casimir I of Kuyavia being Elizabeth's maternal great-great-grandfather and Louis' maternal great-grandfather. A papal dispensation was thus necessary, but it was only sought four months after the wedding took place. The historian Iván Bertényi suggests that the ceremony may have been hastened by an unintended pregnancy, as the couple had been in contact for years. If so, the pregnancy likely ended in a stillbirth.[10] Elizabeth's mother had apparently died by the time she was married.[11] Louis was dismayed when, upon his father-in-law's death later the same year, Elizabeth's young and ambitious cousin Tvrtko ascended the Bosnian throne.[8] In 1357, Louis summoned the young Ban to Požega and compelled him to surrender most of western Zachlumia as Elizabeth's dowry.[1][12]

The new queen of Hungary subjected herself entirely to her controlling mother-in-law, Elizabeth of Poland. The fact that the young queen's retinue consisted of the same individuals who had served the queen mother indicates that Elizabeth of Bosnia may not even have had her own court. Her mother-in-law's influence prevailed until 1370, when Louis succeeded his maternal uncle, Casimir III, as king of Poland.[4] Elizabeth's maternal uncle, Władysław the White, had also been a candidate for the Polish throne.[13] Following his coronation in Poland, Louis brought Casimir's underage daughters, Anne and Hedwig, to be raised by Elizabeth.[14] Elizabeth, though queen of Poland, was never crowned as such.[15]

The problem of the succession marked Louis' reign. Elizabeth was long considered barren, and a succession crisis was expected after the childless king's death. Her brother-in-law Stephen was heir presumptive until his death in 1354, when his son John replaced him. However, John also died in 1360.[16] A daughter was born to the king and queen in 1365, but the child died the next year.[17] For a few years, John's sister, Elizabeth, was treated as heir presumptive and a suitable marriage for her was being negotiated. Things suddenly took a different course after Elizabeth had three daughters in quick succession; Catherine was born in July 1370, Mary in 1371, and Hedwig in 1373 or 1374.[16] Elizabeth is known to have written a book for the education of her daughters, a copy of which was sent to France in 1374. However, all copies have been lost.[18][19]

On 17 September 1374, Louis granted various concessions to the Polish nobility by the Privilege of Koszyce, in exchange for their promise that a daughter of his would succeed him and that he, Elizabeth or his mother could indicate which one.[20] In Hungary, he focused on the centralization of power as means of ensuring that his daughters' rights would be respected.[21] Securing marriage to one of the princesses was a priority in European royal courts.[16] Mary was scarcely one year old when she was promised to Sigismund of Luxembourg.[22] In 1374, Catherine was betrothed to Louis of France,[16] but died towards the end of 1378. The same year, Hedwig, promised to William of Austria in a sponsalia de futuro, left her mother's court and moved to Vienna, where she spent the next two years.[23] The Polish lords swore to uphold Mary's rights in 1379, while Sigismund received this recognition three years later. Elizabeth was present, along with her husband and mother-in-law, at a meeting in Zólyom on 12 February 1380, whereby Hungarian lords confirmed Hedwig's Austrian match; this indicates that Louis may have intended to leave Hungary to Hedwig and William.[24]

The king, weakened by illness, became progressively less active in the last years of his reign, devoting an increasing amount of time to prayer, as did his aging mother, who had returned from Poland in 1374. These circumstances allowed Elizabeth to assume a more prominent role at court. Her influence had grown steadily since she had given her husband heirs. It appeared probable that the crowns would pass to one of Elizabeth's underage daughters and by 1374, their rights were confirmed.[25] Behind the scenes, Elizabeth began ensuring that the succession would be as smooth as possible by encouraging a slow but decisive change in the personnel of the government. Warlike and illiterate barons were gradually replaced by a small group of noblemen who excelled in their professional skills but were not distinguished by birth or military ability. Palatine Nicholas I Garai led the movement and enjoyed the full support of the queen, and their power eventually became virtually unrestricted.[25]

Widowhood and regency

Louis died on 10 September 1382, with Elizabeth and their daughters at his bedside.[26] Elizabeth, now queen dowager, had Mary crowned "king" of Hungary only seven days later. Halecki believes that the reason behind Elizabeth's haste and Mary's masculine title was the dowager's desire to exclude Sigismund, her prospective son-in-law, from the government.[27] Acting as regent on behalf of the eleven-year-old sovereign, Elizabeth made Garai her chief adviser. Her rule was not to be peaceful. The royal court was pleased with the arrangement, but Hungarian noblemen were unwilling to defer to a woman and objected to Mary's accession, maintaining that the lawful heir to the throne was King Charles III of Naples, the only remaining male Angevin. Charles was, at that time, unable to claim Mary's throne because his own was threatened by Duke Louis I of Anjou.[28]

The first to rise against Elizabeth, in 1383, was the prior of Vrana, John of Palisna, who was primarily opposed to the centralizing policy which her husband had enforced. Her cousin Tvrtko also decided to take advantage of Louis' death and Elizabeth's unpopularity by trying to recover the lands he had lost to the king in 1357. Tvrtko and John formed an alliance against Elizabeth, but they were ultimately defeated by her army, with John being forced to flee to Bosnia.[29]

Polish succession

.png.webp)

Although Louis had designated Mary as his successor in both of his kingdoms, the Polish nobles, seeking an end to the personal union with Hungary, were not willing to recognize Mary and her fiancé Sigismund as their sovereigns.[30] They would have accepted Mary if she had moved to Kraków and reigned over both kingdoms from there rather than from Hungary, ruling according to their advice rather than that of the Hungarian nobles and marrying a prince of their choosing. Their intentions, however, were not to Elizabeth's taste. She too would have been required to move to Kraków, where a lack of men loyal to her would have rendered her unable to enforce her own will. Elizabeth was also aware of the difficulties her mother-in-law had faced during her regency in Poland, which had ended with the old queen fleeing her native kingdom in disgrace.[31]

An agreement was reached between Elizabeth's and Polish delegates in Sieradz on 26 February 1383.[32] The queen dowager thereby proposed her youngest daughter Hedwig as Louis' successor in Poland,[31][33] and absolved the Polish nobles from their 1382 oaths to Mary and Sigismund.[32][33] She agreed to send Hedwig to be crowned in Kraków but requested that, in view of her age, she spend three more years in Buda following the ceremony. The Poles, entangled in a bloody civil war, initially conceded to the requirement, but soon found it unacceptable for their monarch to reside abroad for so long. At the second meeting in Sieradz, held on 28 March, they contemplated offering the crown to Hedwig's distant relative, Duke Siemowit IV of Masovia.[33] They eventually opted against it, but at the third Sieradz meeting, on 16 June, Siemowit himself decided to lay claim to the crown. Elizabeth reacted by having an army of 12,000 men devastate Masovia in August, forcing him to drop his pretensions.[34] Meanwhile, she realized that she could not expect the nobles to accept her request and instead resolved to delay Hedwig's departure. Despite continuous Polish demands to expedite her arrival, Hedwig did not move to Kraków until the end of August 1384.[35] She was crowned on 16 October 1384.[36][37] No regent was appointed, and the 10-year-old exercised her authority according to the advice of Kraków magnates.[38] Elizabeth never saw her again.[39]

In 1385, Elizabeth received an official delegation from Grand Duke Jogaila of Lithuania, who wished to marry Hedwig. In the Act of Kreva, Jogaila promised to pay compensation to William of Austria on Elizabeth's behalf and requested that Elizabeth, as widow of King Louis and heiress of Poland herself as great-grandniece of King Władysław I (whose name Jogaila had purposely assumed on his baptism), legally adopt him as her son in order to give him a claim to the Polish crown in the event of Hedwig's death.[40][41] The marriage was celebrated in 1386.[36]

Mary's marriage

Mary's fiancé Sigismund and his brother Wenceslaus, king of Germany and Bohemia, were also opposed to Elizabeth and Garai. The queen dowager and the Palatine, on the other hand, were not enthusiastic about Sigismund reigning together with Mary. Both Sigismund and Charles schemed to invade Hungary; the former intended to marry Mary and become her co-ruler, while the latter intended to depose her. Elizabeth was determined to allow neither and, in 1384, started negotiating Mary's marriage to Louis of France, notwithstanding her daughter's engagement to Sigismund. Had this proposal been made after Catherine's death in 1378, the Western Schism would have represented a problem, with France recognising Clement VII as pope and Hungary accepting Urban VI. However, Elizabeth was desperate to avoid an invasion in 1384 and unwilling to let the schism stand in the way of the negotiations with the French. Clement VII issued a dispensation which annulled Mary's betrothal to Sigismund, and her proxy marriage to Louis was celebrated in April 1385, but it was not recognized by the Hungarian noblemen, who adhered to Urban VI.[42]

Elizabeth's plan to have Mary married to Louis of France divided the court. The Lackfis, the master of the treasury Nicholas Zámbó and the judge royal Nicholas Szécsi openly opposed it and renounced their allegiance to the queen dowager in August, which resulted in her depriving them of all their offices and replacing them with Garai's partisans. The kingdom was on the verge of a civil war when Charles decided to invade, encouraged by John Horvat and his brother Bishop Paul of Zagreb. Charles' imminent arrival forced Elizabeth to yield and abandon the idea of French marriage. While her envoys in Paris were preparing for Louis's journey, Elizabeth came to terms with her opponents and designated Szécsi as the new palatine.[43] Four months after her proxy marriage to Louis, Sigismund entered Hungary and married Mary, but the reconciliation between the factions turned out to be too late to forestall Charles' invasion. Sigismund fled to his brother's court in Prague in the autumn of 1385.[43]

Deposition and restoration

Charles's arrival was well-prepared. He was accompanied by his Hungarian supporters and Elizabeth was unable to raise an army against him or prevent him from convoking a diet, in which he obtained an overwhelming support. Mary was forced to abdicate, opening the path for Charles to be crowned on 31 December 1385.[43] Elizabeth and Mary were compelled to attend the ceremony[44] and swear allegiance to him.[45]

Deprived of authority, Elizabeth feigned friendly feelings for Charles while his retinue was at the court, but after his supporters had returned to their homes, he was left defenseless.[46] She acted quickly and invited him to visit Mary in Buda Castle. Upon his arrival there on 7 February 1386, Elizabeth had Charles stabbed in her apartments and in her presence. He was taken to Visegrád, where he died on 24 February.[44][46]

Having had the crown restored to her daughter, Elizabeth immediately proceeded to reward those who had helped her, giving a castle in Gimes to Blaise Forgách, the master of the cupbearers, who had mortally wounded Charles. In April, Sigismund was brought to Hungary by his brother Wenceslaus and the queens were pressured into accepting him as Mary's future co-ruler by the Treaty of Győr.[46] Having Charles murdered did not help Elizabeth as much as she hoped it would, however, as Charles's supporters immediately recognized his son Ladislaus as heir[47] and fled to Zagreb. Bishop Paul pawned church estates in order to collect money for an army against the queens.[48]

Death and aftermath

Elizabeth believed that her daughter's mere presence would help calm the opposition.[46] Accompanied by Garai and a modest following,[46] she and Mary set out for Đakovo.[47] However, Elizabeth had seriously misjudged the situation. On 25 July 1386, they were ambushed en route and attacked by John Horvat in Gorjani.[46][47] Their small entourage failed to fight off the attackers. Garai was killed by the rebels and his head was sent to Charles's widow Margaret, while the queens were imprisoned in the bishop of Zagreb's castle of Gomnec.[46] Elizabeth took all blame for the rebellion and begged the attackers to spare her daughter's life.[49]

Elizabeth and Mary were soon sent to Novigrad Castle, with John of Palisna as their new jailer.[47] Margaret insisted that Elizabeth be put to death.[50] She was tried and, after the Christmas adjournment of the proceedings, found guilty of inciting Charles' murder.[51] Sigismund marched into Slavonia in January 1387, with the intention to reach Novigrad and rescue the queens.[52] Towards the middle of January, when news of Sigismund's approach reached Novigrad, Elizabeth was strangled by guards before Mary's eyes.[47][51][52]

Mary was released from the captivity by Sigismund's troops on 4 June.[51] Having been secretly buried in St Chrysogonus's Church in Zadar on 9 February 1387, Elizabeth's body was exhumed on 16 January 1390, transferred by sea to Obrovac and then carried overland to Székesfehérvár Basilica.[53]

Legacy

Elizabeth was regarded by her contemporaries as an efficient and powerful but ruthless politician who used political intrigues to protect and defend her daughters' rights.[54] She seemed to be a caring parent, but may have lacked political flexibility to prepare Mary and Hedwig for their roles as monarchs. Elizabeth did not set a passable example for her daughters, and her questionable methods in politics would serve partially as a warning to the young sovereigns. Her procrastination threatened Hedwig's future status in Poland, while the problems with Croatian nobles and strained relations with her native Bosnia made Mary's reign insecure and tumultuous.[39]

Queen Elizabeth commissioned the creation of the Chest of Saint Simeon around 1377. The chest, located in Zadar, is of great importance for the history of the city, as it depicts various historical events – such as the death of her father – and Elizabeth herself. According to legend, she stole the saint's finger and paid for the creation of the casket in order to atone for her sin.[55] The casket contains a scene which allegedly depicts the queen gone mad after stealing the relic.[56]

Genealogical table

Notes

- Engel 1999, p. 163.

- Kellogg 1936, p. 9.

- Rudzki 1990, p. 47.

- Engel 1999, p. 171.

- Instytut Historii (Polska Akademia Nauk)

- Van Antwerp Fine 1994, p. 323.

- Várdy, Grosschmid & Domonkos 1986, p. 226.

- Gromada & Halecki 1991, p. 40.

- Michael 1997, p. 303.

- Bertényi 1989, p. 89.

- Gromada & Halecki 1991, p. 88.

- Van Antwerp Fine 1994, p. 369.

- Várdy, Grosschmid & Domonkos 1986, p. 147.

- Jasienica 1978, p. 6.

- Rożek 1987, p. 49.

- Engel 1999, p. 169.

- Gromada & Halecki 1991, p. 49.

- Jansen 2004, p. 13.

- Johnson & Wogan-Browne 1999, p. 203.

- Reddaway 1950, p. 193.

- Engel 1999, p. 174.

- Engel 1999, p. 170.

- Gromada & Halecki 1991, p. 69.

- Gromada & Halecki 1991, p. 73.

- Engel 1999, p. 188.

- Gromada & Halecki 1991, p. 75.

- Gromada & Halecki 1991, p. 97.

- Engel 1999, p. 195.

- Van Antwerp Fine 1994, p. 395.

- Goodman & Gillespie 2003, p. 208.

- Varga 1982, p. 41.

- Przybyszewski 1997, p. 7.

- Gromada & Halecki 1991, p. 101.

- Przybyszewski 1997, p. 8.

- Przybyszewski 1997, p. 97.

- Goodman & Gillespie 2003, p. 221.

- Gromada & Halecki 1991, p. 109.

- Przybyszewski 1997, p. 10.

- Gromada & Halecki 1991, p. 85.

- McKitterick 2000, pp. 709–712.

- Rowell 1996, pp. 10–11.

- Goodman & Gillespie 2003, pp. 222–223.

- Engel 1999, pp. 196–197.

- Grierson & Travaini 1998, p. 236.

- Gromada & Halecki 1991, p. 146.

- Engel 1999, p. 198.

- Van Antwerp Fine 1994, pp. 396–397.

- Šišić 1902, p. 50.

- Duggan 2002, p. 231.

- Gaži 1973, p. 61.

- Gromada & Halecki 1991, p. 164.

- Engel 1999, p. 199.

- Petricioli 1996, p. 196.

- Parsons 1997, p. 16.

- Stewart 2006, p. 210.

- Filozofski fakultet u Zadru, 455.

- Gromada & Halecki 1991, pp. 40, 88.

- Creighton 2011, p. 69.

- Kosáry & Várdy 1969, p. 418.

References

- Bertényi, Iván (1989). Nagy Lajos király. Kossuth Könyvkiadó. ISBN 963-09-3388-8.

- Creighton, Mandell (2011). A History of the Papacy During the Period of the Reformation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-04106-5.

- Duggan, Anne J. (2002). Queens and Queenship in Medieval Europe: Proceedings of a Conference Held at King's College London, April 1995. Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-881-1.

- Engel, Pal (1999). Ayton, Andrew (ed.). The realm of St. Stephen: a history of medieval Hungary, 895–1526 Volume 19 of International Library of Historical Studies. Penn State Press. ISBN 0-271-01758-9.

- Radovi: Razdio filoloških znanosti. Vol. 9. Filozofski fakultet u Zadru. 1976.

- Gaži, Stephen (1973). A History of Croatia. Philosophical Library.

- Goodman, Anthony; Gillespie, James (2003). Richard II: The Art of Kingship. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926220-9.

- Grierson, Philip; Travaini, Lucia (1998). Medieval European coinage: with a catalogue of the coins in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, Volume 14. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-58231-8.

- Gromada, Tadeusz; Halecki, Oskar (1991). Jadwiga of Anjou and the rise of East Central Europe. Social Science Monographs. ISBN 0-88033-206-9.

- Instytut Historii (Polska Akademia Nauk) (2004). Acta Poloniae Historica, Issues 89–90 (in Polish). Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich.

- Jansen, Sharon L. (2004). Anne of France: lessons for my daughter – Library of medieval women. DS Brewer. ISBN 1-84384-016-2.

- Jasienica, Paweł (1978). Jagiellonian Poland. American Institute of Polish Culture. ISBN 978-1-881284-01-7.

- Johnson, Ian Richard; Wogan-Browne, Jocelyn (1999). The idea of the vernacular: an anthology of Middle English literary theory, 1280–1520 Library of medieval women. Penn State Press. ISBN 0-271-01758-9.

- Kellogg, Charlotte (1936). Jadwiga, Queen of Poland. Anderson House.

- McKitterick, Rosamond (2000). Jones, Michael (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History: c. 1300–c. 1415. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36290-3.

- Kosáry, Domokos G.; Várdy, Steven Béla (1969). History of the Hungarian Nation. Danubian Press.

- Michael, Maurice (1997). The Annals of Jan Długosz: An English Abridgement, Part 1480. IM Publications. ISBN 1-901019-00-4.

- Parsons, John Carmi (1997). Medieval Queenship. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-17298-2.

- Petricioli, Ivo (1996). Srednjovjekovnim graditeljima u spomen (in Croatian). Književni krug.

- Przybyszewski, Bolesław (1997). Saint Jadwiga, Queen of Poland 1374–1399. Veritas Foundation Publication Centre. ISBN 0-948202-69-6.

- Reddaway, William Fiddian (1950). The Cambridge history of Poland. Cambridge University Press.

- Rowell, Stephen C. (1996). "Forging a Union? Some Reflections on the Early Jagiellonian Monarchy". Lithuanian Historical Studies. 1: 6–21. doi:10.30965/25386565-00101001.

- Rożek, Michał (1987). Polskie koronacje i korony (in Polish). Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza. ISBN 83-03-01913-9.

- Rudzki, Edward (1990). Polskie królowe (in Polish). Vol. 1. Instytut Prasy i Wydawnictw "Novum".

- Stewart, James (2006). Croatia. New Holland Publishers. ISBN 1-86011-319-2.

- Šišić, Ferdo (1902). Vojvoda Hrvoje Vukc̆ić Hrvatinić i njegovo doba (1350–1416) (in Croatian). Zagreb: Matice hrvatske.

- Van Antwerp Fine, John (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.

- Várdy, Steven Béla; Grosschmid, Géza; Domonkos, Leslie S. (1986). Louis the Great: King of Hungary and Poland. East European Monographs. ISBN 0-88033-087-2.

- Varga, Domonkos (1982). Hungary in greatness and decline: the 14th and 15th centuries. Hungarian Cultural Foundation. ISBN 0-914648-11-X.

External links

Media related to Elizabeth of Bosnia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Elizabeth of Bosnia at Wikimedia Commons