Jennie Bosschieter

Jennie Bosschieter (1883–1900) was a 17-year-old girl who was raped and murdered in Paterson, New Jersey, on October 19, 1900.[1] She was an early victim of the date rape drug chloral hydrate which caused her death. Her death received national news coverage and was described as "one of the most revolting [crimes] ever committed in New Jersey."

Early life

Martijntje "Jennie" Bosschieter was born on April 21, 1883, in the village of Melissant, South Holland, the Netherlands. She was the second daughter of Johannis "John" Bosschieter (1846-1929) and his second wife Dina Kaslander Bosschieter (1861-1953). Jennie had seven siblings: Susie, Gabriel, Joseph, John, Cora, Martin, and Lena. And three half-siblings: Aart, Leonard, and Aggie. When Jennie was seven years old, her family left the Netherlands for America. They settled in Paterson, New Jersey, around 1890. At the time of her murder she lived with her parents at 155 East Fifth Street in the Riverside section, and worked at the Paterson Ribbon Company on Vreeland Avenue.

Murder

Jennie left home on October 18, 1900, at approximately 8pm to purchase baby powder for a young niece at the drug store, where she encountered William A. Death (pronounced "Deeth") and Andrew Campbell. Jennie had previously dated Death but he had abruptly dropped her and married another woman, five weeks earlier. She spoke to them for a few minutes and headed inside the store. While she was inside, Walter McAlister, a wealthy young man, approached Death. McAlister suggested Death invite Jennie to go to Saal's Saloon, which was located nearby at the corner of River Street and Bridge Street.[2]

Death persuaded Jennie to go to the saloon with him and Campbell. While they were there, McAlister dropped in, as if by accident, and while Jennie's back was turned, he spiked her absinthe frappe with chloral hydrate. When she did not pass out immediately, McAlister put a second dose of chloral hydrate into her drink---an amount which turned out to be lethal.[2] When Jennie passed out, McAlister called his friend George, who was waiting at a nearby hotel, and he hired a cab to pick up the group. They took the girl to a secluded area, raped her, and she died sometime during the assault from the effects of the drug. When the men couldn't revive her, they grew frantic and went to the home of a doctor, who came outside and pronounced Jennie dead.[2]

At the doctor's insistence, the men left with the girl's body. Jennie was found a few hours later, lying a short distance away from the Wagaraw bridge (now known as the Lincoln Ave. Bridge) on the Bergen County, New Jersey, side of the Passaic River in Columbia Heights section what is now Fair Lawn, between 5:30 and 6:15 am. The discovery was made by Marinus Gary on his way to work. Her head rested on a jagged rock, and there was a fracture of her skull near the base of her brain. Initially, the skull fracture was thought to be the cause of death but it was determined the damage to her skull was postmortem. The description of her body at discovery was made in an article in the Trenton Times dated October 20, 1900 "She lay as though asleep. She was stretched out on her back, he hands lying at her side, palms downward and fingers relaxed. One leg crossed the other at the ankle. Her dress was not disturbed and was stretched at full length." The coroner estimated the time of death to have been two to three hours before discovery.

An article in the Newark Daily Advocate dated January 29, 1901, described the account of the carriage driver, Augustus Sculthorpe, who came forward to police and gave them a break in the case. According to the report, Sculthorpe told police that on October 19 he was called to Saal's saloon and that at midnight, four men carried an unconscious girl from the saloon to his coach. Sculthorpe says he then drove out to a road house, which was closed. Sculthorpe said he then started back towards Paterson. Somewhere on the road the girl was taken from the hack and "ill treated."

George J. Kerr, Walter C. McAlister, Andrew J. Campbell, and William A. Death were indicted for her murder and arraigned on November 17, 1900, before Judge Dixon. Newspapers at the time made clear that the attackers were not "wild boys" but were instead "old enough to know the meaning of consequences." They were described as "men of families well known and respected in Paterson."

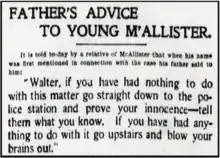

The city of Paterson was shocked. McAlister was from a very wealthy, respectable family in Paterson. The McAlisters owned a number of businesses and employed a substantial number of Paterson residents at their mill and breweries. McAlister's father, who had spent decades establishing his reputation in the city, was so humiliated by the accusation, he offered his son some harsh advice which was reprinted in the local papers.

George Kerr's family was similarly affluent and his father was a devoutly religious man. George's brother John was a judge and his brother-in-law was the mayor of Paterson. George himself was married and, at the time of the attack, his wife was eight months pregnant with his sixth child. Death had married into a prosperous family just over a month before the crime. Campbell was working class and the youngest of the men, but he was very well thought of. Of all the men, there was the most doubt of Campbell's guilt.

All four men pleaded not guilty. The trial was set for January 14 of the following year. Walter C. McAlister, Andrew J. Campbell, and William A. Death were tried together. At the last minute, newspapers announced George Kerr would be tried separately. Several outlets incorrectly reported that George had turned state's evidence, but this was not true. He had not been present when the drug that killed Jennie was administered.[2]

Jennie's parents attended the trial, as did Death's young wife Charlotte, Judge John Kerr, and others.[2] At the trial the defense tried to blame her death on the absinthe and not the overdose of chloral hydrate. They blamed Jennie's parents for letting her go out. They blamed Jennie for accepting the men's invitation. They suggested she had victimized the men who stood accused of her murder. The jury rejected that the death was from the absinthe and that the murder was premeditated. The men were found guilty of murder in the second degree for her killing and sentenced to thirty years imprisonment at hard labor.

George initially entered a plea of Not Guilty, but after the other men were found guilty, George changed his plea to the charge of rape to "non vult contendere" or No Contest. He was sentenced to fifteen years imprisonment at hard labor.

All four sentences were the maximum the law would allow. The appeals of the men were rejected.

Legacy

Jennie's murder received national press coverage for months after her death. The scandalous nature of her death and the power dynamics between her and her murderers drove much of the interest in the story. Jennie was a working class girl; the men who attacked her were wealthy and powerful.

There was a possible copycat crime on March 12, 1901, with Mary Paige drugged, raped and found severely ill, however, Paige did recover. Three boys were convicted of assault and served brief sentences.

Others

- Marinus Gary, who found the body, worked for Alyea Brothers feed mill

- Augustus Sculthorp, the carriage driver

- William Vroom, the coroner

- Frederick Graul, chief of police

- Christopher Saal, owner of the saloon

- Judge Dixon, the Judge who heard the trial of the four men accused of murdering Jennie Bosschieter

- Joseph Bosschieter (b. 1884), Jennie's brother who was born in the Netherlands

- Susie Bosschieter (b. 1881), Jennie's sister who was born in the Netherlands

Further reading

- New York Times; January 9, 1901. "Within an Hour Jury Is Selected to Try the First Case. McAlister, Campbell, and Death Listen Nonchalantly to Testimony of the Victim's Family and Witnesses of the Crime. Separate Trial for Kerr. McAllister's Plea for a Review Denied." "The first case taken up by Judge Dixon in the Supreme Court today was the application of George J. Kerr for a separate trial on the indictment charging him with assaulting and murdering Jennie Bosschieter, and of Walter C. McAllister for removal of the indictment to the Supreme Court, to the end that it may be reviewed and quashed ..."

- New York Times; January 15, 1901. "Paterson, New Jersey; January 14, 1901. The trial of three of the four men who are accused of the murder of Jennie Bosschteter was begun in the Court of Oyer and Terminer, in the old Court House, in Main Street, today. The three men – Walter McAlister, Andrew Campbell, and William Death – who are the persons most concerned in the progress and outcome of the ..."

- New York Times; January 20, 1901. "Paterson, New Jersey; January 19, 1901. The verdict in the Bosschieter case was the principal topic of conversation here today. In every shop, in every public place, the fate of Walter J. McAlister, Andrew J. Campbell, and William A. Death was discussed. So far as could be judged from a general expression of opinion, the verdict pleased."

- New York Times; April 22, 1907. "Bosschieter Convict Seeks Pardon."

- New York Times; May 30, 1908. "Bosschieter Slayer Seeks Pardon."

- "Attacked by the Gang". New York Daily News. October 26, 2008. Retrieved October 29, 2008.

On a mild October evening in 1900, a pretty teenager named Jennie Bosschieter walked to a drugstore from her home in Paterson, N.J., to fetch baby powder for an infant niece.

External links

- Jennie Bosschieter at Find a Grave

- The Poisoned Glass by Kimberly Tilley on Amazon

References

- "Factory Girl Found Dead. Skull Fractured and the Paterson Police Think She Was Murdered" (PDF). New York Times. October 21, 1900. Retrieved August 21, 2007.

Paterson, New Jersey; October 20, 1900. The body of Jennie Bosschieter was found lying a short distance from the Wagaran bridge, on the Bergen side of the Paterson River at 5:30 o'clock this morning. The discovery was made by two milkmen. The head of the girl rested upon a jagged rock, and there was a fracture of the skull near the base of the brain.

- Tilley, Kimberly (2019). The Poisoned Glass (1st ed.). Black Rose Writing. ISBN 978-1-68433-292-2.