Jennie Goodell Blow

Jennie Goodell Blow (née Matteson Goodell) (1860 – January 26, 1935) was a prominent American-born socialite. Blow resided in a number of different locations during her life. Hailing from a prominent family, married to a wealthy man, and reputed for her beauty, Blow established herself as a leading society figure in several different cities. While residing in the United Kingdom, she was a leader in the successful effort to convert the Maine into a hospital ship during the Boer War. The idea for this effort had been Blow's. She worked with Lady Randolph Churchill and Fanny Ronalds to lead this effort and was recognized for it by Queen Victoria and later Edward VII.

Jennie Goodell Blow | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Born | Jennie Mateson Goodell 1860 Joliet, Illinois |

| Died | January 26, 1935 London, U.K. |

| Spouse |

Albert Allmand Blow (died) |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Mary Goodell Grant (sister) Joel Aldrich Matteson (grandfather) James Benton Grant (brother-in-law) |

Biography

Born Mary Matteson Goodell in Joliet, Illinois in 1860,[1][2] she was one of five daughters born to Roswell Eaton Goodell and Mary Matteson Goodell (née Mary Jane Goodell).[3] In addition to her sisters, Mary, Clara, Olive, and Jennie, her parents also had a son named Roswell Eaton Goodell Jr.[3][4] Her maternal grandfather, Joel Aldrich Matteson, was a former governor of Illinois. Her maternal ancestry can be traced back to Mayflower pilgrims John Alden and Priscilla Alden, who were her great-great-great-grandparents through her maternal grandmother Mary Fish Matteson.[3]

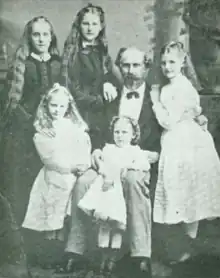

L-R (daughters):

Back row: Mary, Annie; front row: Clara, Olive, Jennie

Her family were Protestants. While their personal home was in Joliet at this time, during part of her childhood, she and her family appear to have lived in the Springfield, Illinois of her grandfather Joel Alrich Matteson, particularly in the period after the American Civil War. From 1870 until 1873, she and her family resided abroad in France and Dresden, Germany. When they returned in the United States, they moved to Chicago, Illinois.[3]

Despite all being Protestants, she and her sisters all attended Washington, D.C.'s Georgetown Academy of the Visitation for part of their education.[3]

In 1878, after the Chicago Fire of 1871 and the panic of 1873 likely damaged her family's fortune, the family moved westward to the state of Colorado, where they settled in mining town of Leadville, which was founded as a town that year and not incorporated until the following year. To arrive in Leadville, the family had to travel from Denver by either stagecoach or covered wagon, as this was the only way to travel to the town until the 1880 opening of the Rio Grande Railroad. She, her, mother and her sisters moved with her father into a log house that he had prepared for them ahead of their arrival.[3]

The Goodells established themselves as a prominent Colorado family.[5] In Leadville, she and her four sisters attracted the attention of many eligible suitors. They were described to have been "the belles of Denver and Leadville".In their adulthood, she and her sisters, who were often collectively referred to as the "famous Goodell sisters", were notable figures in Colorado's social scene. They are considered to have been civic leaders in their own rights and each married a man of prominent stature. The sisters also received a reputation of beauty and fashionable dress.[3][6]

She married Allmond A. Blow, who was considered among the most renown American experts in mining. Her husband was wealthy.[6] Through this marriage, she became the daughter-in-law of George W. Blow Jr.[7] (1813–1894), who had served in political office in the Republic of Texas and also had served as a delegate at the Virginia Secession Convention of 1861 and as judge in Norfolk, Virginia.[8]

In October 1891 in Leadville, Blow gave birth to son Allmand Matteson Blow.[9] In September 1897 in Leadville, Blow gave birth to son George Allmand Blow (1897–1947).[7] The Blows would move to South Africa where Allmond A. Blow was manager of a gold mine.[2]

Blow lived a cosmopolitan life and traveled across different areas of the world. Beauty and wealth afforded Blow the ability to establish herself as a leading society figure in several different cities. While living in London, she established herself in the company of the higher social-circle of English society.[6]

In 1899, Blow, while living in London, was a leading force in the Ladies Hospital Ship Fund for South Africa, a successful effort that converted the Maine into a hospital ship for the Second Boer War. Also leading this effort was fellow American-born London socialites Lady Randolph Churchill and Fanny Ronalds.[1][6][4][10] The idea behind the effort had been Blow's.[11][12] They worked with other American-born London socialites to organize the effort.[6] The fund persuaded Atlantic Transport Line leader Bernard N. Baker to gift the committee a cattle freight ship, the Maine.[1] They then proceeded to solicit financial contributions from other American-born women that were residing in London.[1][6] Among those that contributed were Margaret White (wife of Henry White, Nannie Field (wife of Marshall Field), Caroline Winans (wife of Walter W. Winans).[6] While they were also gifted provisions by British firms, they refused to accept financial contributions from the British, only accepting financial contributions from Americans.[6][2] When the ship was ready, they staffed it with American medical workers and turned possession of the ship over to the government of the United Kingdom.[1] Blow, Churchill, and Ronalds were honored for their work by being granted an audience with Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle. In an uncommon sign of respect, Victoria stood while receiving them.[6] In further recognition of her work, in 1901 Edward VII of the United Kingdom granted Blow the decoration of "lady of the Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem".[6]

In his adulthood, Blow's son Allmand Matteson Blow married Dorothy Deneen, the daughter of Illinois governor Charles S. Deneen.[9]

Blow died while in New York City on January 27, 1935. She had been predeceased by her husband.[1][2]

References

- "Mrs. A. A. Blow, Hospital Ship Creator, Dead". Chicago Tribune. January 27, 1935. Retrieved 10 April 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Jennie Goodell Blow". The Wichita Beacon. February 9, 1935. Retrieved 10 April 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Cannon, Helen (Winter 1964). "First Ladies of Colorado Mary Goodell Grant" (PDF). Colorado Magazine. 4 (1). Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Ferril, William Columbus (1911). Sketches of Colorado: being an analytical summary and biographical history of the State of Colorado as portrayed in the lives of the pioneers, the founders, the builders, the statesmen, and the prominent and progressive citizens who helped in the development and history making of Colorado. Western Press Bureau Company. pp. 268–269. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Noel, Thomas J. (11 October 2021). "Grant-Humphreys Mansion". coloradoencyclopedia.org. Colorado Encyclopedia (History Colorado). Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- "Americans Honored". Newspapers.com. Wilkes-Barre Times Leader. August 7, 1901. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- "George Allmand Blow Roster ID 5159". archivesweb.vmi.edu. Virginia Military Institute. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- "TSHA | Blow, George W., Jr". www.tshaonline.org. Texas State Historical Society. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- "Allmand Matteson Blow Roster ID 5670". archivesweb.vmi.edu. Virginia Military Institute. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- "Great Britain: Boer War S.S. Maine Hospital Ship". www.southafricanmedals.com. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- "Mrs. Blow is Enroute Home". Valentine Democrat. May 23, 1901. Retrieved 10 April 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Thurmond, Aubri E. (December 2014). "Under Two Flags: Rapprochement and the American Hospital Ship Maine: A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of the Texas Woman's University Department of History and Government College of Arts and Sciences" (PDF). Texas Women's University. Retrieved 11 April 2023.