Jeremy (film)

Jeremy is a 1973 American romantic-drama film starring Robby Benson and Glynnis O'Connor as two high school students who share a tentative month-long romance.[2][3][4] It was the first film directed by Arthur Barron, and won the prize for Best First Work in the 1973 Cannes Film Festival.[5] Benson was also nominated for a Golden Globe Award for his performance as the title character.[6]

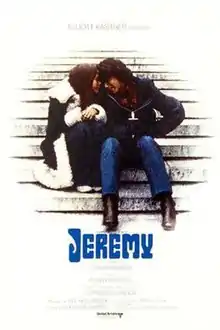

| Jeremy | |

|---|---|

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Arthur Barron |

| Written by | Arthur Barron |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Paul Goldsmith |

| Edited by | Zina Voynow |

| Music by | Lee Holdridge |

Production company | Kenesset Film Productions |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date | May 15, 1973 (Cannes Film Festival)[1] |

Running time | 90 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Plot

Jeremy Jones (Benson) is a shy, bespectacled, Jewish fifteen-year-old living in a New York City apartment with his parents, who are busy with their own pursuits and leave him mostly on his own. He attends a private high school that focuses on the performing arts, where he is a serious student of cello who aspires to musical greatness. He has an after-school job as a dog walker. His other interests include reading poetry, playing chess and basketball, and following horse racing, where he can consistently pick winners, though he never places a bet himself. At school, he enters an empty classroom looking for chalk, sees a girl (O'Connor) inside practicing ballet, and is instantly smitten with her beauty. They talk briefly, but he is flustered and completely forgets to ask her name. He later learns she is a new student named Susan Rollins, and that she is older than him and in a higher grade. Jeremy follows her from a distance for a few days, but is too shy to approach her, so his more confident friend Ralph takes matters into his own hands and explains the situation to her, and she sends the message back to Jeremy that he should call her. However, Jeremy decides not to call after seeing her walking with a handsome older boy. Shortly afterwards, Susan attends a school recital where Jeremy plays the cello as a featured soloist. She is impressed by his playing and congratulates him afterwards, motivating him to finally call her and ask her out.

On their first date, Jeremy finds out that Susan's mother is dead, and that she and her father just moved to New York from Detroit so her father could take a new job. Susan and Jeremy enjoy each other's company and they begin walking to school together every day, visiting places such as the park and racetrack, and generally spending a lot of time together for the next three weeks. Jeremy confides to Ralph that he is falling in love. One rainy afternoon while playing chess in Jeremy's room, Susan and Jeremy profess their love for each other and then make love for the first time.

Susan then returns home, only to find that her father has been offered a better job back in Detroit, so they will be leaving New York immediately, within the next couple of days. Susan tries to explain to her father that she is in love with Jeremy, but her father doesn't take it seriously because he thinks that the "three weeks and four days" that Susan and Jeremy have been seeing each other is not long enough to form a deep relationship. The next day a tearful Susan tells Jeremy the news and he is likewise stunned. He tries to reach out to both his father and Ralph to talk with them about his feelings, but neither one is receptive. In the end, Susan and Jeremy sadly say goodbye at the airport and she departs, leaving Jeremy alone again.

Cast

- Robby Benson – Jeremy Jones

- Glynnis O'Connor – Susan Rollins

- Len Bari – Ralph Manzoni

- Leonardo Cimino – Cello teacher

- Ned Wilson – Susan's father (Ned Rollins)

- Chris Bohn – Jeremy's father (Ben Jones)

- Pat Wheel – Jeremy's mother (Grace Jones)

- Ted Sorel – Music teacher in school

- Bruce Friedman – Shop owner

- Eunice Anderson – Susan's aunt (Eunice)[7]

- Dennis Boutsikaris (uncredited) – Susan's boyfriend (Danny)

Production

Conflicting information has been published regarding the conception, writing and direction of the film. According to author John Minahan, the film was based on his novel Jeremy which he began writing in 1972. He shared a pre-publication draft with his friend Arthur Barron, who was then a screenwriting instructor at Columbia University and a staff writer and producer of documentaries at NBC.[7][8] Barron then wrote a screenplay based on the book, assembled a cast with the help of his wife (a former casting director), and recruited his friends Elliott Kastner and George Pappas to produce the film and help him sell it to United Artists.[8] (Minahan's novel was meanwhile published as a Bantam paperback[9] and widely distributed in the U.S. via Scholastic Book Services, coinciding with the holiday 1973 general release of the film.)[8]

However, as documented in an article that appeared Variety in June 1973, Joseph Brooks, who was then a composer of advertising and film music, filed a dispute with United Artists claiming that he rather than Barron had conceived the film, written most of the script, cast and packaged the film with Kastner producing, and directed most of the film until Kastner fired him and replaced him with Barron, who according to Brooks had been an assistant. Kastner contended that Barron had been contracted as co-writer and co-director, and that Kastner replaced Brooks with Barron after Brooks fired Robby Benson and then went over budget. United Artists remained neutral, saying the dispute was between Brooks and Kastner.[7][10] New York Times film critic Roger Greenspun wrote that "it seems fair to suggest that, in whatever proportion, both [Brooks and Barron] were involved in the authorship of the film."[11] In the end, Brooks received full credit only for composing the theme song "Blue Balloon (The Hourglass Song)", although The New York Times continued to recognize his directorial claim.[12]

Jeremy marked the professional acting and film debut of Glynnis O'Connor,[7][13] and the breakthrough role for Benson. The two stars began dating in real life during production, leading to a long-term relationship,[14] and they appeared again in the 1976 film Ode to Billy Joe.

Similar to the character he played, Benson had a hobby of handicapping and betting on horse races, and had even worked as a horse walker at the Aqueduct Racetrack until the time demands of making Jeremy forced him to quit.[14]

Filming was done on location at a variety of Manhattan and Long Island locations, including Park Avenue, the High School of Performing Arts, the Mannes College of Music, and Belmont Park racetrack.[13]

Reception

Jeremy received generally positive reviews,[11][13] including favorable comparisons to the hit films Love Story[11] and Summer of '42, which had similar subject matter about young people coming of age through falling in love. Roger Greenspun called it "true and moving" despite "indulging almost every cliche available to young love in Manhattan."[11] Writing in The New York Times, Rosalyn Drexler called the film "as honest and sympathetic a story about young love as I've ever seen," adding, "Robby Benson is funny, enthustiastic, and intelligent; able to play scenes as if they were entirely spontaneous. It is his presence that gives 'Jeremy' its most attractive quality, a kind of wholehearted plunge into youth's critical rites of passage."[15] Gene Siskel gave the film three-and-a-half stars out of four and that "much of the credit for the film's success belongs to its principal actors, Robby Benson and Glynis O'Connor. They are both capable of expressing a wide range of emotion, and the script gives them the opportunity for such expression. Their performances ring with honesty and candor."[16] Variety wrote that director Barron "handles this slight but glowing pic with insight" and that the final scenes were "executed touchingly."[17] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times called it "a well-made film with a documentary-like feeling for upper Manhattan ... but you can be rendered uneasy by the mixture in 'Jeremy' of a notably well observed physical reality and an uncommonly romanticized make-believe."[18] Tom Shales of The Washington Post wrote that "even if one wants to believe this happy vision and put oneself at the movie's mercy, the improbable and uneventful screenplay, also credited to Barron, makes that difficult. In short, it depicts Jeremy and Susan as a pair of rich little bores."[19]

Some controversy was caused by the nude sex scene between Benson and O'Connor, who were both 16 years old and thus minors at the time of filming.[14] Benson stated in an interview that his parents had consented to the scene (which was filmed on a closed set) on the conditions that no frontal nudity be shown, and that he and O'Connor not be fully nude (according to Benson, they both wore flesh-colored underwear).[20]

In a 1970s study of "love-shy" men done by Dr. Brian G. Gilmartin, with "love-shyness" being defined as "shyness that prevails in coeducational or man/woman situations wherein there is no purpose but pure, unadulterated friendliness and sociability", Jeremy ranked as the favorite film among the 300 love-shy men in the study. Many of the men had seen the film more than once, with 17 men seeing it 20 or more times. One 39-year-old man had seen it 86 times, and another 43-year-old man had seen it 42 times and then spent $1,000 to obtain his own 16 mm "underground" (illegal) print of the film, despite having an income of only $9,000 per year and receiving food stamp assistance. According to Gilmartin, the appeal of the film to the love-shy men in his study was due to O'Connor's physical appearance and the love-shyness of the title character as played by Benson.[21]

Soundtrack

The soundtrack was released in 1973 on LP by United Artists Records (UA-LA145-G). The soundtrack was composed by Lee Holdridge, and it contained two original songs:[22]

- "Blue Balloon (The Hourglass Song)", sung by Robby Benson and written by Joseph Brooks

- "Jeremy", sung by Glynnis O'Connor and written by Lee Holdridge and Dorothea Joyce

See also

References

- "Cannes: Lineup of Main Items." Variety. May 9, 1973. 104.

- "MGM's 2005 Romance Promotion: Jeremy (January 19/05)". reelfilm.com. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- "Review: 'Jeremy'". variety.com. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- "Jeremy". timeout.com. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- "Festival de Cannes: Jeremy". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- "Jeremy". upcomingdiscs.com. Archived from the original on 2013-12-13. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- "AFI Catalog of Feature Films: Jeremy". afi.com. American Film Institute. 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-04-03. Retrieved 2015-11-20.

- Minahan, John (2001). The Music of Time: An Autobiography. Lincoln, Nebraska: Writer's Showcase (iUniverse). pp. 290–297. ISBN 0-595-20073-7.

- Minahan, John (1973). Jeremy. New York City: Bantam Books. ISBN 0553105493.

- "Campus Teacher Barron Credited Unfairly For 'Jeremy', Declares Brooks; Kastner Angry; UA, Guild Neutral". Variety. New York City: 4. 1973-06-03. Retrieved 2015-11-22 – via Variety.com.

- Greenspun, Roger (1973-08-02). "Jeremy (1973): Very Young Love Story, 'Jeremy', Is on Screen: The Cast". The New York Times. New York City. Retrieved 2015-11-17 – via Nytimes.com.

- Lichtenstein, Grace (1977-12-25). "These Days, Movies Light Up His Life". The New York Times. New York City. p. 63. Retrieved 2015-11-17 – via NYTimes.com.

- "Movie at Temple, 'Jeremy', is Story of a First Love". The Kane Republican. Kane, Pennsylvania. 1974-01-29. Retrieved 2015-11-25 – via Newspapers.com.

- Boyle, Hal (1973-08-05). "Film Romance Turns Out To Be Real Thing". The Salina Journal. Salina, Kansas. Retrieved 2015-11-25 – via Newspapers.com.

- Drexler, Rosalyn (August 12, 1973). "'Jeremy'—A Big 'Little' Movie". The New York Times. Section 2, p. 1, 13.

- Siskel, Gene (October 15, 1973). "Jeremy". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 7.

- "Film Reviews: Jeremy". Variety. May 23, 1973. 18.

- Champlin, Charles (September 21, 1973). "Young Love in Afternoon of '72". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 1.

- Shales, Tom (September 27, 1973). "Young Love in Candyland". The Washington Post. B17.

- The Moviegoer (1973-09-17). "Romance in Film Becomes Real". Deseret News. Salt Lake City, Utah. Retrieved 2015-11-25 – via News.google.com.

- Gilmartin, Dr. Brian G. (1987). Shyness & Love: Causes, Consequences, and Treatment. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America. pp. 474, 477, 482–483. ISBN 0819161020.

- "Lee Holdridge – Jeremy (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) (1973, Vinyl) - Discogs". Discogs.

men