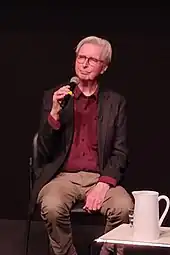

Jerome Hiler

Jerome Hiler (born March 27, 1943) is an American experimental filmmaker, painter, and stained glass artist.

Early life

Hiler was born on March 27, 1943 in Jamaica, Queens.[1] He grew up in a religious Catholic family.[2] He enjoyed classical music, particularly Igor Stravinsky. In high school, Hiler enrolled in a program at the Pratt Institute where he learned painting from Natalia Pohrebinska. He was inspired by the abstract expressionists of the time. He followed Jonas Mekas's column in The Village Voice and travelled into Manhattan to attend screenings at the Bleecker Street Cinema.[2][3]

After graduating high school, Hiler moved into a storefront in the East Village and took a job as a runner on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange. After being kicked out of a shared artist's loft on Eldridge Street, he moved into a Bowery hotel. He met filmmaker Gregory Markopoulos, who had cast a friend of Hiler's in The Illiac Passion, and moved into his Greenwich Village apartment.[1][2]

Career

1963–1971: New York and New Jersey

Hiler became an assistant for Markopoulos, designing costumes and scouting locations for The Illiac Passion. He borrowed a Bolex 16 mm camera from Markopoulos and tried began photographing street scenes.[1][3] He met Nathaniel Dorsky after the 1964 premiere of Dorsky's Ingreen, and the two became romantic partners.[3]

Hiler worked as a projectionist alongside Robert Cowan, at The Film-Makers' Cinematheque at 125 West 41st St. in New York City.[4] He was the first projectionist for Andy Warhol's Chelsea Girls and went on to project that film more than 150 times.[5] He continued shooting film during this time, preferring reversal film for its speedier development process. This also gave him the ability to continually re-edit his footage in apartment screenings he held regularly.[1][6]

Hiler and Dorsky moved to rural Lake Owassa, New Jersey in 1966.[7] Hiler's first completed film was an untitled work given as a gift for Dorsky's birthday. Dorsky made one in response, and the two pieces are now known as Fool's Spring (Two Personal Gifts).[3]

1971–present: San Francisco

Hiler moved with Dorsky to San Francisco in 1971, where they became involved with Canyon Cinema and San Francisco Cinematheque.[2][7] Hiler re-established his practice of holding regular private screenings of his work; however, he did not complete or release any films for many years.[2][6] During this time, he worked as a carpenter, the caretaker for a convent, and a stained glass artist.[8] His next film Gladly Given was made when Silt, a local film collective, offered to organize a public screening. It was edited in camera as Hiler shot three rolls of film without remembering what had already been recorded on each one, resulting in multiple superimpositions.[2][3] The film was later screened at the 1997 New York Film Festival. Photographer Frederick Eberstadt commissioned his 2001 film Target Rock.[8]

Starting in 2010, Hiler began releasing films regularly. Music Makes a City, a documentary co-directed with Owsley Brown III, depicts the resurgence of the Louisville Orchestra, with musical interludes scored to landscape images. Words of Mercury experiments with multiple superimpositions. It screened at the New York Film Festival and the Whitney Biennial.[6] In the Stone House is edited from footage taken from Hiler's time in New Jersey during the 1960s, and New Shores uses footage from the same period, but shot in California.[2]

Style

Hiler creates experimental films. An Artforum review by P. Adams Sitney of his 2011 film, Words of Mercury, described Hiler as part of the "rare company of significant if almost invisible filmmakers of the American avant-garde cinema."[8] Manohla Dargis of The New York Times wrote that Hiler's "output is limited but stunning."[9] Wheeler Winston Dixon has described his films as works in which "everyday objects, places, things and people are transformed into integers of light, creating a sinuous tapestry of restless imagistic construction."[1]

Filmography

- Fool's Spring (Two Personal Gifts) (co-made with Nathaniel Dorsky) (1966)

- Library (co-made with Nathaniel Dorsky) (1970)

- Gladly Given (1997)

- Target Rock (2000)

- Music Makes a City (2010)

- Words of Mercury (2011)

- In the Stone House (1967–70/2012)

- New Shores (1979–90/2012)

- Misplacement (2013)

- Bagatelle II (1964–2016)

- Bagatelle I (2016–2018)

- Marginalia (2016)

- Ruling Star (2019)[10]

References

- Dixon, Wheeler Winston (1997). The Exploding Eye: A Re-Visionary History of 1960s American Experimental Cinema. SUNY Press. pp. 77–82.

- Hiler, Jerome; McGinnes, Mac (February 27, 2020). "Hidden in Plain Sight: Jerome Hiler and Mac McGinnes in Conversation". San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

- MacDonald, Scott (2006). A Critical Cinema 5: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers. University of California Press. pp. 87–109.

- Anderson, Steve (July 1999). "The Exploding Eye: A Re-Visionary History of 1960s American Experimental Cinema". Film Quarterly. 52 (4): 44–45. doi:10.1525/fq.1999.52.4.04a00090. ISSN 0015-1386.

- The Chelsea Girls: An Interview with Jerome Hiler, San Francisco Cinematheque, 2014-10-13, retrieved 2020-05-20

- Goldberg, Max (2012). "Return to Form: An Interview with Jerome Hiler". Cinema Scope. No. 52. p. 48.

- Sitney, P. Adams (November 2007). "Tone Poems". Artforum. Vol. 46, no. 3. pp. 341–347. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- Sitney, P. Adams (March 2012). "P. Adams Sitney on Jerome Hiler's Words of Mercury". Artforum. Vol. 50, no. 7. Retrieved 2020-05-20.

- Dargis, Manohla (2015-09-24). "For Nathaniel Dorsky and Jerome Hiler, Film Is the Star". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-05-20.

- "Jerome Hiler". Canyon Cinema. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

External links

- Jerome Hiler at IMDb