Jerome Myers

Jerome Myers (March 20, 1867 – June 19, 1940) was an American artist and writer associated with the Ashcan School, particularly known for his sympathetic depictions of the urban landscape and its people.[1] He was one of the main organizers of the 1913 Armory Show, which introduced European modernism to America.[2]

Jerome Myers | |

|---|---|

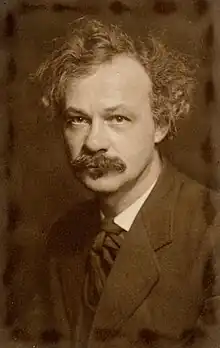

Jerome Myers ca. 1910 | |

| Born | March 20, 1867 |

| Died | June 19, 1940 (aged 73) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Cooper Union, Art Students League |

| Known for | Painting, drawing, pastels, etching |

| Notable work |

|

| Movement | New York Realists, Ashcan School |

| Spouse | Ethel Myers |

Born in Petersburg, Virginia, and raised in Philadelphia, Trenton and Baltimore, he spent his adult life in New York City. Myers worked briefly as an actor and scene painter. He then studied art for a year at Cooper Union followed by study at the Art Students League over a period of eight years where his main teacher was George de Forest Brush. In 1896 he went to Paris, but only stayed a few months, believing that his main classroom was the streets of New York's Lower East Side. His strong interest and feelings for the new immigrants resulted in over a thousand drawings, as well as paintings, etchings and watercolors that depicted their lives outside of the tenements which were their first homes in America.

In a 1923 magazine article he explained why cities were his greatest source of inspiration:

All my life I had lived, worked and played in the poorest streets of American cities. I knew them and their population and was one of them. Others saw ugliness and degradation there, I saw poetry and beauty, so I came back to them. I took a sporting chance of saying something out of my own experience and risking whether it was worthwhile or not. That is all any artist can do.[3]

Life and career

Early years

Born in Petersburg, Virginia, Jerome Myers was one of Abram and Julia Hillman Myers' five children. His brother, Gustavus Myers, later became a prominent muckraking journalist, socialist activist, and historian. As their father was often absent, the Myers children were raised by their mother and eventually lived in Trenton, New Jersey, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. From time to time, the siblings were placed in foster homes when their mother was ill. Given these family hardships, Myers began taking odd jobs at a young age, living in Baltimore, Maryland, before moving on to New York City. Arriving in Manhattan in 1886 at the age of nineteen, Myers worked for several years as a scene painter and later for the Moss Engraving Company, where he reproduced photographic negatives. During this time he began attending evening art classes at Cooper Union and the Art Students League. Even then, his interest in urban subjects was evident. Myers' earliest oil painting, Backyard (1888), depicting a clotheslines silhouetted against distant tenements, is today thought to be one of the first paintings exemplifying Ashcan School subject matter in America.[4] Similarly, around 1893, after sketching a canal boat during a day trip along the Morris and Essex Canal, Myers made his first sale to the woman who lived on the boat. The price was two dollars.[5]

Becoming a professional artist

In 1895, Myers found work in the art department of the New York Tribune. With savings of two hundred and fifty dollars from this job, he traveled to Paris in 1896. Upon his return to New York City, with only twenty dollars left, he rented, for seven dollars a month, a studio at 232 West 14th Street in a former five-story mansion, "equipped with a skylight and converted to the use of artists."[6] There, his next door neighbor was Edward Adam Kramer, a painter just one year older than Myers himself. While Myers' art training had been limited to short stints at New York's Cooper Union and the Art Students League, Kramer had acquired his education in the European art centers of Munich, Berlin, and Paris. It was Kramer who ushered Myers into the world of the professional artist. One day, when the art dealer William Macbeth arrived at Kramer's studio to view work, Kramer directed him to Myers' studio as well. Macbeth purchased two small paintings of his early New York street scenes from Myers on the spot, and simultaneously recommended that he bring additional work to the gallery. Macbeth thought highly of these two paintings and, taking them to his gallery, soon sold one to the banker, James Speyer. As an early critic for the New York Globe stated: "Myers' reputation dates from that purchase."[7] Macbeth also suggested that Myers relinquish drawing in pencil and pastel and turn to oils. In the years following 1902, Myers sold work through the Macbeth Gallery and exhibited in group shows at other venues. In March and April 1903, when the Colonial Club of New York held its annual art show, Exhibition of Paintings Mainly by New Men, among the twenty artists included were Robert Henri, John French Sloan, and Myers, showing their works together for the first time.

Summer in Manhattan

For Jerome Myers, summer in Manhattan provided particular opportunities for depicting immigrant life in the urban landscape. The hot weather brought the tenement dwellers out into the streets and parks of the city. By July 1906, Myers' reputation as an artist depicting the life of the people on the Lower East Side was such that a New York Times reporter was assigned to him, beginning at five o'clock one morning, to observe the artist capturing likenesses of the adults at work and children at play. To walk through the East Side with Myers, the reporter noted, "turning off here and there to glance at some particular house or group of people, ... [was] to receive an impression of a joyous life lived in the open air for much the same reason as people live in that fashion in Europe—because their homes are not as comfortable as the streets."[8] Individual responses to Myers' presence, however, were grounded in cultural differences. While the residents of Italian neighborhoods viewed the artist and his activities with excitement and curiosity, those of the Jewish Quarter, whose traditions often forbade the production of representational images, protested by moving away from the artist's range of vision.[8]

Later years

Myers won the Altman Prize for Street Shrine in 1931 and again in 1937 for City Playground. He was awarded the National Academy's Carnegie Prize in 1936 and the Isidor Medal in 1938. In 1934 the Metropolitan Museum of Art had purchased the painting Street Group from the Municipal Art Exhibition in Rockefeller Center. The New York Herald Tribune reported:

the painting by Mr. Myers is of a group of women standing talking in a somber street, with children playing about them. Mr. Myers considers it typical of his work, and says it is the sort of scene he most enjoys to paint. "Old streets and old houses and the people who live in them," he explained. "I am trying to catch the New York that is passing," he said. "I painted that down on Delancey Street seven or eight years ago and already the scene has changed in spirit. I want to get it before it is gone."

Twenty two years earlier, in 1912, the Metropolitan had made its first purchase of a Myers painting, The Mission Tent. The June 1913 Metropolitan Museum Bulletin wrote:

Jerome Myers for several years has been showing New Yorkers the artistic possibilities of what is perhaps the unique part of the city's scenes. He has discovered these subjects for himself and treats them in his own way. It is never the exciting moments of street life that move him, only the daily happenings, the usual things that all may see. Boys and girls playing in the square, the crowd at a recreation pier, an organ-grinder followed by a troop of dancing children, old people whom the night freshness lures to the park-bench or the wharf, a religious festival in Little Italy—these are his favorite themes and he renders them with loving sincerity and a profound appreciation of their significance.

Not only was the sale to the Metropolitan a great honor then, but it also provided him with enough money to move his family from their small studio into a more spacious one in the new Carnegie Hall.[10] Over the years, despite moving around to various studios, he always came back to Carnegie as his real home.

Myers died in his Carnegie studio on June 19, 1940, after a series of illnesses complicated by an injury sustained from a fall. He was 73.[10][11] Earlier that year, he had published his autobiography, Artist In Manhattan. In their obituary for Myers, published in July 1940, The Art Digest wrote:

Though Myers later achieved wide honors—he was elected to the Academy and awarded such important prizes as the Altman, the Carnegie and the Isidor Medal—he suffered from neglect in recent years. Forgotten, for the most part, were Myers' distinctive contributions to our native art and the battles he has fought for art freedom.[12]

In April–May 1941 the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City held the Jerome Myers Memorial Exhibition with over 90 of his paintings, drawings and etchings lent by museums throughout the United States as well as private collectors. The oil paintings exhibited ranged from his 1905 The Tambourine to a self-portrait completed in 1939, the year before his death.[9] Myers was survived by his wife and fellow artist Ethel Myers whom he had married in 1905 and their daughter, the dancer Virginia Myers. Following her husband's death Ethel devoted much of her time to furthering his artistic reputation. She lectured on his work throughout the United States, under the auspices of the American Federation of Arts from 1941 to 1943 and maintained the Jerome Myers Memorial Gallery in New York City for a number of years.[13]

Gallery

Band Concert Night, 1910, oil on canvas

Band Concert Night, 1910, oil on canvas Wonderland, 1921, oil on canvas

Wonderland, 1921, oil on canvas Waiting for the Concert, 1921, oil on canvas

Waiting for the Concert, 1921, oil on canvas Evening on the Pier, 1921, oil on canvas

Evening on the Pier, 1921, oil on canvas

Museums holding Jerome Myers' work

- Addison Gallery of American Art

- Arkansas Arts Center

- Arkell Museum

- Art Gallery of Hamilton

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Barnes Foundation

- Blanton Museum of Art

- Boston University

- Brooklyn Museum of Art

- Butler Institute of American Art

- Carnegie Museum of Art

- Claremont Colleges

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Columbus Museum (Georgia)

- Columbus Museum of Art (Ohio)

- Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum

- Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

- Corcoran Gallery of Art

- Currier Museum of Art

- Delaware Art Museum

- Denver Art Museum

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Emerson Gallery, Hamilton College

- Everson Museum of Art

- Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

- Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center

- Georgia Museum of Art

- Greenville County Museum of Art

- Heckscher Museum of Art

- Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art

- High Museum of Art

- Hillstrom Museum of Art, Gustavus Adolphus College

- Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

- Hood Museum of Art

- Hunter Museum of American Art

- Huntington Library

- Indianapolis Museum of Art

- Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts

- Joslyn Art Museum

- Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art

- Kennesaw State University

- Library of Congress

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- Maier Museum of Art

- Mead Art Museum

- Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Milwaukee Art Museum

- Minneapolis Institute of Arts

- Montclair Art Museum

- Museum of Art at Brigham Young University

- Museum of Art Fort Lauderdale

- Museum of the City of New York

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute

- Muskegon Museum of Art

- Nashville Parthenon

- National Academy of Design

- National Gallery of Art

- National Portrait Gallery (United States)

- Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

- New Britain Museum of American Art

- New York Historical Society

- New York Public Library

- Norton Museum of Art

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Phillips Collection

- Portland Art Museum

- Princeton University Art Museum

- Quick Center for the Arts, St. Bonaventure University

- Saint Joseph College

- Santa Barbara Museum of Art

- Seattle Art Museum

- Sheldon Museum of Art

- Smithsonian American Art Museum

- Southern Illinois University

- Spencer Museum of Art

- Staten Island Institute of Arts & Sciences

- Syracuse University

- Telfair Museum of Art

- Ulrich Museum of Art, Wichita State University

- University of Iowa Museum of Art

- University of Wyoming

- Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

- Washington County Museum of Fine Arts

- Westmoreland Museum of American Art

- Williams College Museum of Art

- Whitney Museum of American Art

- Wichita Art Museum

- Yale University Art Gallery

- Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University

References

- "Jerome Myers". Smithsonian American Art Museum and Renwick Gallery. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- "1913 Armory Show: The Story in Primary Sources". Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- "The Life Song of the People: Paintings and Sketches by Jerome Myers". The Survey: 33–39. October 1, 1923.

- Holcomb, Grant (May 1977). "The Forgotten Legacy of Jerome Myers (1867-1940) Painter of New York's Lower East Side". American Art Journal, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 78-91. Retrieved via Jstor.org 25 July 2015 (subscription required).

- Perlman, Bennard B. (2010). Ashcan humanists: John Sloan & Jerome Myers. Scranton, PA: Hope Horn Gallery, the University of Scranton.

- Myers, Jerome (1940). Artist in Manhattan, p. 25. New York: American Artists Group, Inc.

- Holcomb III, Grant (1970). The Life and Art of Jerome Myers (Masters' thesis). University of Delaware

- "Life on the East Side his Art Inspiration," New York Times, July 1, 1906.

- Wickey, Henry (1941). Jerome Myers Memorial Exhibition. Whitney Museum of American Art

- "Jerome Myers Papers, 1904-1967, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-12-18. Retrieved 2015-07-24.

- New York Times (20 July 1940). "Jerome Myers, 73, Noted Artist Dies", p. 23. Retrieved 24 July 2015 (subscription required for full access).

- "Jerome Myers Passes". The Art Digest. July 1, 1940.

- Columbus Museum. Creator Record: Myers, Ethel. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

External links

Media related to Jerome Myers at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Jerome Myers at Wikimedia Commons- Video: Artist In Manhattan on YouTube

- Video: Jerome Myers Visits The Burlesque on YouTube