Jeronimus Cornelisz

Jeronimus Cornelisz (c. 1598 – 2 October 1629) was a Dutch apothecary and Dutch East India Company merchant who sailed aboard the merchant ship Batavia which foundered near the Australian mainland. Cornelisz then led one of the bloodiest mutinies in history.

Jeronimus Cornelisz | |

|---|---|

| Born | Unknown date, c. 1598 |

| Died | 2 October 1629 (aged 30–31) |

| Occupation(s) | Apothecary, merchant |

| Employer | Dutch East India Company |

| Known for | Mutiny amongst and massacre of survivors of the Batavia wreck |

Criminal charge | Mutiny, murder |

Criminal penalty | |

| Spouse | Belijtgen van der Knas (1626) |

| Parent(s) | Kornelis Jeroens, Sytske Douwes |

After the ship was wrecked in the Houtman Abrolhos, a chain of coral islands off the west coast of Australia, on 4 June 1629, Francisco Pelsaert, the expedition's commander, went to get help from the settlements in the Dutch East Indies, returning several months later.

While Pelsaert was away, Cornelisz led one of the bloodiest mutinies in history, for which he was eventually tried, convicted and hanged.

Early life

Cornelisz was probably born in the Frisian capital of Leeuwarden, where he grew up in a nonconformist household. His mother—and likely his father, too—belonged to the Netherlands' Mennonite Church, members of an Anabaptist church. It has been speculated that they may have had links with some of the more militant Anabaptist movements, such as the Batenburgers, that flourished in the Dutch Republic during the 16th century.

The young Jeronimus was well educated, probably at the Latin School at Dokkum, and followed his father into the family trade by training to become an apothecary. He qualified around the year 1623, and practiced in his home town until 1627. He left that year apparently as a result of disagreements with the town council. Cornelisz moved to the much larger Dutch city of Haarlem, where he opened up an apothecary shop near the centre of the town.

In November 1627, he and his wife had a son, but the child died after fewer than three months after being placed in the care of a wet nurse. The cause of death was established as syphilis, considered a scandal, and Cornelisz became embroiled in a legal action against the nurse, seeking to prove that his child had contracted the disease from her and not from his wife. With his reputation and future business prospects destroyed, Cornelisz was forced to realize what he could by selling off his shop and assets.

Batavia

Whether or not Cornelisz actually was acquainted with Johannes van der Beeck, he left Haarlem within a few weeks after the painter's trial and the ruin of his own prospects. Cornelisz went to Amsterdam and took service with the Dutch East India Company (VOC). He was posted to the Batavia, which sailed for Java in the Dutch East Indies, in October 1628. Sea voyages in this era were often marked by deaths from shipboard epidemics of infectious and nutritional deficiency disease, scurvy being particularly common.

Cornelisz, whose main motive in signing on such a venture seems to have been to escape his degraded social and economic position, allegedly became friendly with the Batavia's skipper, Ariaen Jacobsz, in the course of the ship's long voyage. He and Jacobsz supposedly became discontented with the leadership of the commander of the ship, the VOC commodore, Francisco Pelsaert, and according to the book later written by Pelsaert, almost immediately plotted a mutiny – although this would have been an extremely difficult undertaking given it was a major VOC ship with a paid crew and armed soldiers guarding valuables.

Shipwreck

For some reason, Pelsaert stayed in his cabin for much of the voyage, even though he was responsible for the ship. He later claimed the confession tortured out of Cornelisz confirmed that Jacobsz had deliberately steered the Batavia off course. The ship subsequently ran aground on a reef in the Abrolhos Islands and was lost.

More than 200 survivors made their way ashore, where they discovered there was no shelter, food, nor drinking water. As deaths from dehydration began, Pelsaert, Jacobsz, and all the officers left in the only boat, and although telling the others they were taking a trip looking for water, they eventually embarked on a month-long voyage to Java.

Mutiny

Cornelisz was left on the island with people of lower status and was able to establish himself as a leader. This could not be considered a mutiny as no proper authority had been appointed by the officers before their hasty departure. Cornelisz's rule in the Abrolhos became criminal when he aimed at removing those who the very limited food and water would have to be shared with. Some were tricked and secretly killed. Others, such as a group of soldiers including Wiebbe Hayes, were sent to a nearby island to search for water. The only other candidate for chief was the minister, who saw his family—apart from his daughter—killed and was intimidated thereafter. Rain eventually ameliorated the drinking water problem; food, however, remained insufficient.

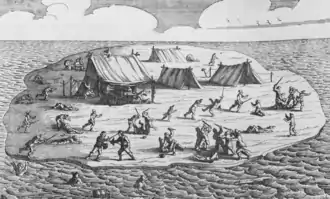

Cornelisz established a brutal personal rule in the islands, backed by men who had plotted with him on board ship. When later questioned, they said they had been obeying orders from the recognized leader that Cornelisz seemed to be. At first covertly, then more and more openly, the survivors not in Cornelisz's faction were killed or sent away to the near islands or escaped there. In all, Cornelisz and his henchmen were responsible for the deaths of between 110 and 124 men, women, and children over a two-month period. Their victims were drowned, strangled, hacked to pieces, or bludgeoned to death, singly or in large groups. Seven surviving women were forced into sexual slavery, with Cornelisz reserving Lucretia Jans for himself. Cornelisz's faction then began killing those dispersed on the other various islands, who presented a threat through now being collectively more numerous than his own men.

Capture

.jpg.webp)

The group of soldiers—including Wiebbe Hayes—that had been dispatched to a nearby island to search for water, unexpectedly found it. They sent a smoke signal, which drew survivors that then warned of the killings. They set up a hilltop stonework defense against the Cornelisz faction, which now faced a forewarned and re-enforced group in good health. After a pair of unsuccessful attacks, Cornelisz tried personally to negotiate with Hayes's men before moving in for a final attack.

According to Pelsaert's account, he arrived at exactly the right moment—aboard the Sardam—to stop Cornelisz's lieutenants from annihilating the resistance, and thwarting an intention to seize the rescue ship, massacre its crew, and turn pirate in the Indian Ocean. How Cornelisz and his band armed with few muskets could possibly have hoped to overcome a Dutch East India Company ship's crew and marines is not explained by the account given in Pelsaert's book.

Execution

Cornelisz and his men were subsequently tortured into confession. In the Pelsaert account that is the only source, a strictly Calvinist worldview of the time portrays Cornelisz as an inherently evil disbeliever in Hell, although his group swore religious oaths. Cornelisz himself maintained he was simply trying to make sure he survived. Cornelisz was tried on the islands, found guilty of mutiny, and hanged along with half a dozen of his men. Both of his hands were amputated with a hammer and chisel prior to the hanging. The remaining mutineers were taken back to Java and tried; many were subsequently executed. Ariaen Jacobsz apparently died in the dungeons of Castle Batavia.

VOC authorities were not impressed with Pelsaert's stewardship of their valuable ship and assets, and he was not allowed to take up the post he had been sailing to.

Personality

In the historical work, Batavia's Graveyard, which analyzes the incident based on research in Dutch archives, among other sources, author Mike Dash theorizes that Cornelisz was almost certainly psychopathic and probably suffered from neurosyphillis.

Dash suggests this is shown by Cornelisz's often erratic behavior on the islands, his unattainable dreams of setting up a personal kingdom in the islands, and his complete assurance that he could do no wrong and that God himself inspired all of his deeds. Dash argues that this is connected to heretical ideas that he had picked up during his supposed acquaintance with the controversial painter Johannes van der Beeck.

Bibliography

- Commelin, I., ed. (1647). Ongeluckige Voyagie, Van't Schip Batavia (in Dutch). Amsterdam: J. Jansz. OCLC 1049972433.

- Dash, M. (2003). Batavia's Graveyard: the mad heretic who led history's bloodiest mutiny. London: Orion Books. ISBN 9780753816844.

- Drake-Brockman, H. (2006). Voyage to Disaster: the life of Francisco Pelsaert. Nedlands: UWA Publishing. ISBN 9781920694722.

- Gerritsen, R. (2009). "Australia's first military conflict in 1629" (PDF). Sabretache. 50 (4): 5–10. ISSN 0048-8933.

- Gerritsen, R. (2011). Australia's first criminal prosecutions in 1629 (PDF). Watson: Batavia Online Publishing. ISBN 9780987214126.

- Leys, S. (2005). The Wreck of the Batavia. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 9781560258216.

- Lydon, J. (2018). "Visions of Disaster in the Unlucky Voyage of the Ship Batavia" (PDF). Itinerario. 42 (3): 351–374. doi:10.1017/S016511531800058X. S2CID 166085539.

- Roeper, V. D. (2002). De schipbreuk van de Batavia, 1629 (in Dutch). Zutphen: Walburg Pers. ISBN 9789057302343.

- Sparrow, J. (April 2015). "Bring up the bodies". The Monthly. Essays. ISSN 1832-3421. Retrieved 2 September 2019.