Jeulmun pottery period

The Jeulmun pottery period (Korean: 즐문 토기 시대) is an archaeological era in Korean prehistory broadly spanning the period of 8000–1500 BC.[1] This period subsumes the Mesolithic and Neolithic cultural stages in Korea,[2][3] lasting ca. 8000–3500 BC ("Incipient" to "Early" phases) and 3500–1500 BC ("Middle" and "Late" phases), respectively.[4] Because of the early presence of pottery, the entire period has also been subsumed under a broad label of "Korean Neolithic".[5]

| Geographical range | Korean peninsula |

|---|---|

| Period | Neolithic |

| Dates | c. 8000 – c. 1500 BC |

| Followed by | Mumun pottery period |

| Korean name | |

| Hunminjeongeum | |

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Jeulmun togi sidae |

| McCune–Reischauer | Chŭlmun t'ogi sidae |

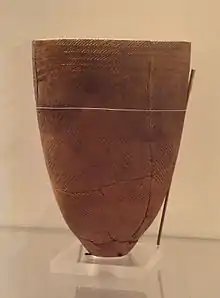

The Jeulmun pottery period is named after the decorated pottery vessels that form a large part of the pottery assemblage consistently over the above period, especially 4000-2000 BC. Jeulmun (Hangul: 즐문, Hanja: 櫛文) means "Comb-patterned". A boom in the archaeological excavations of Jeulmun Period sites since the mid-1990s has increased knowledge about this important formative period in the prehistory of East Asia.

The Jeulmun was a period of hunting, gathering, and small-scale cultivation of plants.[6] Archaeologists sometimes refer to this life-style pattern as "broad-spectrum hunting-and-gathering".

Incipient Jeulmun

The origins of the Jeulmun are not well known, but raised-clay pattern Yunggimun pottery (Korean: 융기문토기; Hanja: 隆起文土器) appear at southern sites such as Gosan-ni in Jeju-do Island and Ubong-ni on the seacoast in Ulsan. Some archaeologists describe this range of time as the "Incipient Jeulmun period" and suggest that the Gosan-ni pottery dates to 10,000 BCE.[2][7] Samples of the pottery were radiocarbon dated, and although one result is consistent with the argument that pottery emerged at very early date (i.e. 10,180±65 BP [AA-38105]), other dates are somewhat later.[8] If the earlier dating holds true, Yunggimun pottery from Gosan-ni would be, along with central and southern China, the Japanese Archipelago, and the Russian Far East, among a group of the oldest known pottery in world prehistory. Kuzmin suggests that more absolute dating is needed to gain a better perspective on this notion.[9]

Early Jeulmun

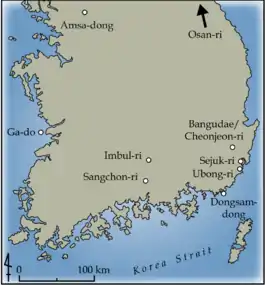

The Early Jeulmun period (c. 6000-3500 BC) is characterized by deep-sea fishing, hunting, and small semi-permanent settlements with pit-houses. Examples of Early Jeulmun settlements include Seopohang, Amsa-dong, and Osan-ri.[10] Radiocarbon evidence from coastal shellmidden sites such as Ulsan Sejuk-ri, Dongsam-dong, and Ga-do Island indicates that shellfish were exploited, but many archaeologists maintain that shellmiddens (or shellmound sites) did not appear until the latter Early Jeulmun.[5]

Middle Jeulmun

Choe and Bale estimate that at least 14 Middle Jeulmun period (c. 3500-2000 BC) sites have yielded evidence of cultivation in the form of carbonized plant remains and agricultural stone tools.[11] For example, Crawford and Lee, using AMS dating techniques, directly dated a domesticated foxtail millet (Setaria italica ssp. italica) seed from the Dongsam-dong Shellmidden site to the Middle Jeulmun.[12] Another example of Middle Jeulmun cultivation is found at Jitam-ri (Chitam-ni) in North Korea. A pit-house at Jitam-ri yielded several hundred grams of some carbonized cultigen that North Korean archaeologists state is millet.[13][14] However, not all archaeologists accept the grains as domesticated millet because it was gathered out of context in an unsystematic way, only black-and-white photos of the find exist, and the original description is in Korean only.

Cultivation was likely a supplement to a subsistence regime that continued to heavily emphasize deep-sea fishing, shellfish gathering, and hunting. "Classic Jeulmun" or Bitsalmunui pottery (Hangul: 빗살무늬토기) in which comb-patterning, cord-wrapping, and other decorations extend across the entire outer surface of the vessel, appeared at the end of the Early Jeulmun and is found in West-central and South-coastal Korea in the Middle Jeulmun.

Late Jeulmun

The subsistence pattern of the Late Jeulmun period (c. 2000-1500 BC) is associated with a de-emphasis on exploitation of shellfish, and the settlement pattern registered the appearance of interior settlements such as Sangchon-ri (see Daepyeong) and Imbul-ri. Lee suggests that environmental stress on shellfish populations and the movement of people into the interior prompted groups to become more reliant on cultivated plants in their diets.[15] The subsistence system of the interior settlements was probably not unlike that of the incipient Early Mumun pottery period (c. 1500-1250 BC), when small-scale shifting cultivation ("slash-and-burn") was practiced in addition to a variety of other subsistence strategies. The Late Jeulmun is roughly contemporaneous with Lower Xiajiadian culture in Liaoning, China. Archaeologists have suggested that Bangudae and Cheonjeon-ri, a substantial group of petroglyph panels in Ulsan, may date to this sub-period, but this is the subject of some debate.

Kim Jangsuk suggests that the hunter-gatherer-cultivators of the Late Jeulmun were gradually displaced from their "resource patches" by a new group with superior slash-and-burn cultivation technology and who migrated south with Mumun or undecorated pottery (Hangeul: 무문토기; Hanja: 無文土器). Kim explains that the pattern of land use practiced by the Mumun pottery users, the dividing up of land into sets of slash-and-burn fields, eventually encroached on and cut off parts of hunting grounds used by Jeulmun pottery users.[16]

See also

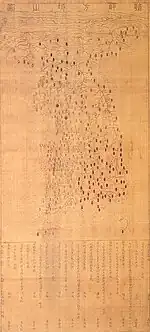

| History of Korea |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

References

- Bale, Martin T. 2001. Archaeology of Early Agriculture in Korea: An Update on Recent Developments. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association 21(5):77-84. Choe, C.P. and Martin T. Bale 2002. Current Perspectives on Settlement, Subsistence, and Cultivation in Prehistoric Korea. Arctic Anthropology 39(1-2):95-121. Crawford, Gary W. and Gyoung-Ah Lee 2003. Agricultural Origins in the Korean Peninsula. Antiquity 77(295):87-95. Lee, June-Jeong 2001. From Shellfish Gathering to Agriculture in Prehistoric Korea: The Chulmun to Mumun Transition. PhD dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison. Proquest, Ann Arbor. Lee, June-Jeong 2006. From Fisher-Hunter to Farmer: Changing Socioeconomy during the Chulmun Period in Southeastern Korea, In Beyond "Affluent Foragers": The Development of Fisher-Hunter Societies in Temperate Regions, eds. by Grier, Kim, and Uchiyama, Oxbow Books, Oxford.

- Choe and Bale 2002

- see also Crawford and Lee 2003, Bale 2001

- Choe, C P and Martin T Bale (2002) Current Perspectives on Settlement, Subsistence, and Cultivation in Prehistoric Korea. Arctic Anthropology 39(1–2): 95–121. ISSN 0066-6939

- Lee 2001

- Lee 2001, 2006

- Im, Hyo-jae 1995. The New Archaeological Data Concerned with the Cultural Relationship between Korea and Japan in the Neolithic Age. Korea Journal 35 (3):31-40.

- Kuzmin, Yaroslav V. 2006. Chronology of the Earliest Pottery in East Asia: Progress and Pitfalls. Antiquity 80:362–371.

- Kuzmin 2006:368

- Im, Hyo-jae 2000. Hanguk Sinseokgi Munhwa [Neolithic Culture in Korea]. Jibmundang, Seoul.

- Choe and Bale 2002:110

- Crawford and Lee 2003:89

- To, Yu-ho and Ki-dok Hwang 1961.Chitam-ni Wonshi Yuchok Palgul Pogo [Excavation Report of the Chitam-ni Prehistoric Site]. Kwahakwon Ch'ulpan'sa, Pyeongyang.

- see also Im 2000:149

- Lee 2001:323; 2006

- Kim, Jangsuk 2003. Land-use Conflict and the Rate of Transition to Agricultural Economy: A Comparative Study of Southern Scandinavia and Central-western Korea. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 10(3):277-321.

Further reading

- Nelson, Sarah M. 1993 The Archaeology of Korea. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.