Königsberg Synagogue

Königsberg's New Synagogue (German: Neue Synagoge) was one of three synagogues in Königsberg in Prussia, East Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia). The other synagogues were Old Synagogue and Adass Jisroel synagogue. The New Synagogue was destroyed in the aftermath of Kristallnacht in 1938. It was reconstructed and reopened in 2018.

| New Synagogue, Königsberg Neue Synagoge (de) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | orthodox Judaism |

| Status | destroyed |

| Location | |

| Location | Königsberg, East Prussia (modern Kaliningrad, Russia) |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Cremer & Wolffenstein |

| Style | Aesopian style |

| Completed | 1896 |

History

In 1508 two Jewish physicians were allowed to settle in the city.[1] 307 Jews lived at Königsberg in 1756. There were 1,027 Jews in Königsberg in 1817. In 1864 there lived 3,024 Jews. In 1880 there were 5,000 Jews at the city. In 1900 there were only 3,975 Jews in Königsberg. The first synagogue was a chapel built in 1680 in Burgfreiheit (a location which was a ducal Prussian immunity district around the castle, not administrated by the city).

In 1704 there was the formation of the Jewish congregation, when they acquired a Jewish cemetery and when they founded a "Chevra Kaddisha". In 1722 they received a constitution. In 1756 a new synagogue in Schnürlingsdamm street was dedicated but destroyed by the city fire in 1811. In 1815 a new synagogue was constructed on the same location, meanwhile called Synagogenstrasse #2. The second constitution of the Jewish congregation was issued in 1811.

Some Orthodox congregants seceded from the Jewish Congregation of Königsberg, which they deemed too liberal, and founded the Israelite Synagogal Congregation of «Adass Jisroel» (German: Israelitische Synagogengemeinde «Adass Jisroel»).[2] In 1893 the Israelite Synagogal Congregation built its own synagogue in Synagogenstraße #14–15. Soon later the mainstream Jewish Congregation of Königsberg built a new and larger place of worship, therefore called New Synagogue, dedicated in August 1896 in Lomse. The synagogue in Synagogenstrasse #2 was called Old Synagogue since.

The New Synagogue, as well as the Old Synagogue, were destroyed in the November Pogrom in the night of November 9–10, 1938. The Adass Jisroel synagogue was terribly vandalised, but spared from arson, and could thus be restored to serve as Jewish place of worship.[3] In July 1939 the Gestapo ordered the merger of the smaller Israelite Synagogal Congregation in the larger Jewish Congregation of Königsberg, which now had to enlist also all non-Jews such as Christians and irreligionists, whom the Nazis categorised as Jews because they had three or more Jewish grandparents. The systematic deportations of Jewish Germans (and Gentile Germans of Jewish descent), starting in October 1941,[4] brought the congregational life in Königsberg to a halt by November 1942.

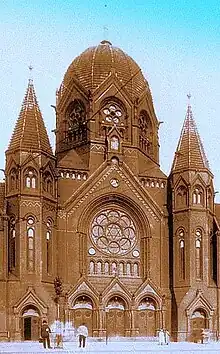

New Synagogue with Lindenstraße (today's ulitsa Oktyabrskaia). Old postcard

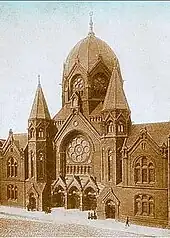

New Synagogue with Lindenstraße (today's ulitsa Oktyabrskaia). Old postcard New Synagogue in 1900

New Synagogue in 1900 New Synagogue, interior. Unknown date

New Synagogue, interior. Unknown date

Reconstruction

In October 2011 the foundation cornerstone of the new synagogue was erected in the same place, where an exact replica of the building destroyed in 1938 was planned.[5] The plaque attached to the cornerstone reportedly was damaged and sprayed with neo-Nazi symbols,[6] but later was cleaned and repaired. The synagogue was reopened in 2018 on the 80th anniversary of its destruction.[7]

Foundation stone and re-construction site of the New Synagogue

Foundation stone and re-construction site of the New Synagogue Rebuilding of New Synagogue, in August 2018

Rebuilding of New Synagogue, in August 2018 The rebuilt New Synagogue, 2019

The rebuilt New Synagogue, 2019

Rabbis

- Solomon Fürst (from 1707 to 1722). He wrote a cabbalistic work and a prayer, which is printed in Hebrew and German language.

- Aryeh (Löb) Epstein ben Mordecai (from 1745 to 1775).

- Samuel Wigdor (from 1777 to 1784).

- Shimshon ben Mordechai (from 1791 to 1794).

- Joshua Bär Herzfeld (from 1800 to 1814).

- Joseph Levin Saalschütz (from 1814 to 1823).

- Wolff Laseron (from 1824 to 1828).

- Jacob Hirsch Mecklenburg (from 1831 to 1865). He who wrote the "Ha-Ketav we-ha-Qabbalah".

- Isaac Bamberger.

- Hermann Vogelstein (from 1897).

Notable members

The community was one of the pioneers of modern culture. Jews of Königsberg have taken an important part in the struggle for the Jewish emancipation:

- Hannah Arendt (1906–1975), political theorist

- Yaakov Ben-Tor (1910–2002), geologist

- Isaac Euchel (pupil of Immanuel Kant). Euchel founded a Hebrew literary society. He wrote the periodical "Ha-Me'assef" and the circular letter "Sefat Emet". Euchel defended institutions for the education of the young pupils, like the "Freischule" at Berlin.

- Hugo Falkenheim (4 September 1856 – 22 September 1945), last Chairman of the Jewish congregation of Königsberg

- Ferdinand Falkson (physician)

- David Friedländer (1750–1834), writer

- Leah Goldberg (1911–1970), author

- Theodor Goldstücker (1821–1872), scholar

- Marcus Herz (pupil of Kant)

- Immanuel Jacobovits, (1921–1999), Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth

- Johann Jacoby (politician)

- Aaron Joel (pupil of Kant). Joel introduced the ideas of Moses Mendelssohn into the city of Königsberg

- Raphael Kosch (physician). In 1869 Kosch secured for Jews the abolition of the Jews' oath in Prussia

- Rudolf Lipschitz (1832–1903), mathematician

- Moshe Meron (born 1926), politician

- Leah Rabin (1928–2000)

- Simon Samuel (physician). Samuel has taken an important part in securing for Jews the right of admission to the faculty of the Albertina University in Königsberg.

- Moritz Simon (financier)

- Samuel Simon (financier)

- Moshe Smoira (1888–1961), first President of the Supreme Court of Israel

- Marcus Warschauer (financier)

- Michael Wieck (1928-2021), violinist and author

In 1942 most of the remaining Jews of Königsberg were murdered in Maly Trostinez (Minsk), Theresienstadt and Auschwitz.

References

- Borowski, Beitrag zur Neueren Geschichte der Juden in Preussen, Besonders in Beziehung auf lhre Freieren Gottesdienstlichen Uebungen, in: Preussisches Archiv, ii., Königsberg, 1790; idem, Moses Mendelssohns und David Kypkers Aufsätze über Jüdische Gebete und Festfeiern, ib. 1791;

- Jolowicz, Geschichte der Juden in Königsberg in Preussen, Posen, 1867;

- Saalschütz, Zur Geschichte der Synagogengemeinde in Königsberg, in Monatsschrift, vi.-ix.;

- Vogelstein, Beiträge zur Geschichte des Unterrichtswesens in der Jüdischen Gemeinde zu Königsberg in Preussen, Königsberg, 1903.

Notes

- "FJC | Communities | Kaliningrad". Archived from the original on 2011-06-17. Retrieved 2009-05-30.

- In the Ashkenazzi pronunciation of Hebrew the words עדת ישראל become Adass Jisroel in German orthography, which was the official name in Latin letters. In English orthography Adas Yisro'el would better represent the Ashkenazzi pronunciation. In Sephardi Hebrew pronunciation, today prevailing, the words עדת ישראל become Adat Yisra'el in English.

- Michael Wieck, Zeugnis vom Untergang Königsbergs: Ein «Geltungsjude» berichtet (11990), Munich: Beck, 82005, (Beck'sche Reihe; vol. 1608), pp. 81 and 194. ISBN 3-406-51115-5.

- The deportations of Jews and Gentiles of Jewish descent from Austria and Pomerania (both to Poland) as well as Baden and the Palatinate (both to France) had remained a spontaneous episode.

- "Kaliningrad Jews battle circus over restoring synagogue".

- "Baltic Republican Party". Archived from the original on 10 July 2012.

- Liphshiz, Cnaan (2018-11-09). "Russia's Westernmost Synagogue Rebuilt 80 Years After Kristallnacht Destruction". The Jewish Week. Retrieved 2018-11-10.