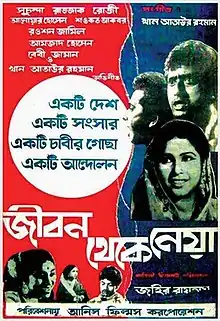

Jibon Theke Neya

Jibon Theke Neya (lit. 'Taken from Life') is a critically acclaimed Bengali-language East-Pakistani film directed by Zahir Raihan. Released in 1970, described as an example of "national cinema", using discrete local traditions to build a representation of the Bangladeshi national identity[2][3]

| Taken from life | |

|---|---|

| |

| Bengali | জীবন থেকে নেয়া |

| Directed by | Zahir Raihan |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Zahir Raihan |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Afzal Chowdhury |

| Edited by | Maloy Banerjee |

| Music by | Khan Ataur Rahman Altaf Mahmud |

| Distributed by | Anees Films Corporation |

Release date |

|

Running time | 133 minutes[1] |

| Country | Pakistan |

| Language | Bengali |

Set against the backdrop of the political and social upreveal in East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh) during the late 1960s, Jibon Theke Neya portrays the struggles and aspirations of the common people in the face of oppression and injustice.[4] The film addresses themes such as poverty, political corruption, political exploitation, and the power of unity.[5]

Zahir Raihan, known for his socially conscious approach to filmmaking, crafted a compelling narrative that resonated with audiences. The film is a political satire based on the 1952 Bengali Language Movement under the rule of Pakistan metaphorically, where an autocratic woman in one family symbolizes the political dictatorship of Ayub Khan in East Pakistan, The film highlights the socio-political issues prevalent in the era and critiques the ruling elite's exploitation of the masses. The film's title, which translates to "Taken From Life" reflects the underlying message that change and progress can only be achieved through collective action and a steadfast commitment to justice. It resonated deeply with audiences in the 70's and became a symbol of resistance against inequality and oppression.[6][7]

Jibon Theke Neya garnered widespread acclaim for its powerful storytelling, poignant performances, and the director's exceptional execution. It played a pivotal role in shaping the trajectory of Bangladeshi Cinema and became a landmark film in the country's history. Moreover, the movie holds historical significance as it was released just months before the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971, which ultimately led to the independence of Bangladesh from Pakistan.The impact and relevance of Jibon Theke Neya continue to be felt today. It remains a cultural touchstone, serving as a reminder of the importance of social justice and the enduring spirit of the Bangladeshi people. The film's legacy endures, and it continues to inspire filmmakers and audiences alike, cementing its place as a timeless classic in Bangladeshi cinema.[8] According to The Daily Star, the film is considered to be Zahir Raihan's finest work till date.[9]

Plot

The story of the film is based on a very ordinary family of Bengal. In one family there are two brothers, Anis (Shawkat Akbar) and Farooq (Razzak), the elder sister Raushan Jamil and the sister's husband Khan Ataur Rahman. Elder sister Raushan Jamil is married. She lives in her father's house. Her husband is very innocent. All the power in the world is in the hands of Raushan Jamil. By abusing this power, she continues to have some kind of dictatorship over her husband and her two brothers. She walks around with a bunch of keys in the area. The housemaid walks around with a drinking bowl behind her. Everyone is restless in her dreadful glory. The character of the then Pakistani dictator has been portrayed in this metaphor. Raushan Jamil's husband Khan Ataur Rahman works as a court employee. Khan Ataur Rahman arranged the marriage of his brother-in-law Shawkat Akbar on the advice of one of his friends. The bride is a quiet, polite girl named Sathi (Rosie Samad). But Raushan Jamil sat completely bent. She is reluctant to marry her brother. He was afraid that the key of the world would not fall and his hand slipped into the hands of his new wife. As a result, Khan Ataur Rahman married his brother without informing Raushan Jamil. Raushan Jamil's sword of oppression came down on her when she became his wife. On the other hand, Farooq alias Razzak fell in love with his younger sister Bithi (Suchanda). If brother-in-law and elder brother give permission, he can also marry Bithi. Sathy and Bithi's elder brother Anwar Hossain. Anwar Hossain is an activist of a political movement. He was imprisoned in the freedom movement. On the other hand, under the leadership of Sathy and Suchanda, everyone in the house became united. Posters are hung on the walls inside their houses. Raushan Jamil's bunch of keys went to the two sisters. The drinking bowl keeps turning behind them. Raushan Jamil lost his power and became crazy and began to make new conspiracies. In the meanwhile, when Sathy and Bithi became pregnant, they were admitted to the hospital. Unfortunately the partner gave birth to a stillborn child. The doctor fears that this grief may not be tolerated by the partner. So Bithi's child was placed in her lap. Thinking it was his own child, the companion began to nurture him. Raushan Jamil conspired and started a dispute between the two sisters. Tactically, he poisoned Bithi and put the blame on her partner. Although Bithi recovered, her partner was arrested on the charge of poisoning. When the case came up in the court, Shawkat Akbar fought the case against his wife, and Khan Ataur Rahman became the lawyer for her partner. Khan Ataur Rahman proved in court that his own wife Raushan Jamil was the main culprit. This is how the story of the film ends.

Cast

- Shuchanda as Bithi

- Razzak as Faruk

- Rosy as Sathi

- Shawkat Akbar as Anis

- Rawshan Jamil

- Khan Ataur Rahman

- Anwar Hossain

- Amjad Hossain as Modhu

- Baby Zaman as Ghotok

Production

The film was originally titled Tinjon meye o ek peyala bish (lit. 'Three Girls and a Cup of Poison').[10] At the request of film producer Anis Dosani, Zaheer Raihan took over the responsibility of making the film. Zaheer Raihan decided that in the story of the film, one sister will poison another sister. Writer Amjad Hossain could not accept this story because he thought that making a film with such a story would not be hit. However, instead of writing the story as per the words of Zaheer Raihan, Amjad Hossain continued to write the story as his own. Amjad Hossain later said in an interview with Prothom Alo that he could not write the story as directed by the director as he could not continue making a documentary film about Amanullah Asaduzzaman due to government objections.[11]

Shooting for the film began on 1 February 1970, but some scenes were recorded a year earlier. Pakistan's military government had repeatedly tried to stop the film. The government threatened the film's director and actor Razzak. The director also received death threats for this film.[10] Film maker Alamgir Kabir attributed the film's uneven production quality to threats to ban it and to the haste with which it was made. Filming was compressed into about 25 shooting days, as little as a third of what was typical in Pakistan at that time.[1]

Music

| Jibon Theke Neya | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Sabina Yasmin, Khan Ataur Rahman, Ajit Roy, Mahmudun Nabi, Nilufar Yasmin, Khandaker Farooq Ahmed and others | |

| Released | 1970 |

| Genre | Film music |

| Language | Bengali |

Khan Ataur Rahman was the music director of this film. Although the use of Tagore Songs was banned by the Information Minister of Pakistan Khwaja Shahabuddin in 1967, a song by Rabindranath Tagore has been used in the film in defiance of that ban.[10]

| No. | Title | Lyrics | Singers | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Eki Sonar Aloy" | Sabina Yasmin | ||

| 2. | "E Khacha Bhangbo Ami" | Khan Ataur Rahman | ||

| 3. | "Amar Sonar Bangla" | Rabindranath Tagore | Ajit Roy, Mahmudun Nabi, Sabina Yasmin, Nilufar Yasmin | |

| 4. | "Karar Oi Louho Kopat" | Kazi Nazrul Islam | Ajit Roy, Khandaker Farooq Ahmed and others | |

| 5. | "Amar Bhaiyer Rokte Rangano" | Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury |

Release

The film was not released on the scheduled date due to government restrictions. As the film was not released, the people of East Pakistan staged protests and demonstrations in various places. So the government cleared the film and released it. The government banned the film after it was released. The military junta later lifted the ban on the film in the face of protests.[12] The film was shown in East Pakistani cinemas for about six months. The film was also screened in Kolkata, capital of Indian Bengal[10] in 1971.[12]

Reception

Critical reception

Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Ritwik Ghatak and Tapan Sinha praised the film.[12] Exactly one month after the release of the film, film journalist Ahmed Zaman Chowdhury wrote in the weekly Chitrali magazine, "Zahir has the ease of editing a film, but lacks overall skills. As a result, there is not always an equation of how long a shot will last. So the application ends before it is spread." According to Bidhan Biberu, the film was able to represent the then Bengali society of Pakistan. Criticizing the film, Alamgir Kabir said that the character of the elder sister in the film is arranged in the style of Ayub Khan and the family shown in the film is compared with the politics of Pakistan at that time. However, according to him, such a family is not realistic in the true sense. He noted that many scenes showed in the film were not perfect.[13]

References

- Kabir, Alamgir (1970). Cowie, Peter (ed.). International Film Guide 1971. London: Tantivy Press. p. 217. ISBN 0-498-07704-7.

- Alam, Shahinur (10 February 2022). জীবন থেকে নেয়া: পারিবারিক গল্পের আড়ালে বলা এক রাষ্ট্রের গল্প. Ittefaq (in Bengali). Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- "Jibon Theke Neya, an emblem of political satire - Young Observer - observerbd.com". The Daily Observer. Retrieved 2023-06-26.

- Correspondent, A. A. "Jibon Theke Neya: Cinema that reflects life | The Asian Age Online, Bangladesh". The Asian Age. Retrieved 2023-06-26.

- Tithi, Naznin (2021-08-19). "Zahir Raihan and the making of Jibon Thekey Neya". The Daily Star. Retrieved 2023-06-26.

- Staff Correspondent (2019-03-25). "'Jibon Theke Neya', an exposure of authority". Prothomalo. Retrieved 2023-06-26.

- "Jibon Theke Neya: A Film of Revolution". corners.news. Retrieved 2023-06-26.

- "The celebs' list of favourite movies based on 1971". The Business Standard. 2021-12-16. Retrieved 2023-06-26.

- Ishtiaq, Ahmad (19 August 2021). জহির রায়হান: অকালে হারানো উজ্জ্বল নক্ষত্র. The Daily Star (in Bengali). Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- Muhammad Altamis Nabil (30 January 2022). জীবন থেকে নেয়া: বাংলাদেশের অস্তিত্বের চলচ্চিত্র. Banglanews24.com (in Bengali). Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- Ali, Masum (10 April 2020). 'জীবন থেকে নেয়া'র ৫০ বছর আজ. Prothom Alo (in Bengali). Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- Mohammad, Jahangir (17 August 2021). ছবির ভাষায় মুক্তির স্বপ্ন. Anandabazar (in Bengali). Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- Biberu, Bidhan (19 August 2015). জীবন থেকে নেয়া : চেতনার রূপকথা (in Bengali). NTV.