Jim Dennistoun

James Robert Dennistoun (7 March 1883 – 9 August 1916) was a New Zealand mountaineer, explorer and airman in the First World War. He is known in particular as the first person to climb to the top of Mitre Peak / Rahotu.

Jim Dennistoun | |

|---|---|

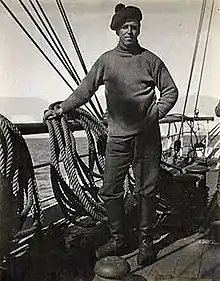

Dennistoun James in 1910 | |

| Birth name | James Robert Dennistoun |

| Born | 7 March 1883 Peel Forest, New Zealand |

| Died | 9 August 1916 (aged 33) Ohrdruf, Germany |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1915–1916 |

| Rank | Lieutenant |

| Unit | No. 23 Squadron RAF |

| Awards | Polar Medal |

Early life

Dennistoun was born the middle of the three children of Emily (née Russell, 1856–1937) and George James Dennistoun (1847–1921) who farmed at Peel Forest Station which is located near the settlement of Peel Forest near Geraldine on the South Island of New Zealand.[1] His siblings were older sister Barbara and younger brother George Hamilton Dennistoun (23 September 1884 – 16 June 1977). Dennistoun attended the Collegiate School in Whanganui and later from 1894 to 1901, Malvern College in England.

After he left school, he took up sheep farming, while his younger brother George eventually went into the navy. He bought a farm at Hawea in April 1910 but ended up selling it in September 1910. He then bought another farm near Lumsden, in the South Island.

Mountain climbing

Attracted by the nearby mountains he became passionate about mountaineering, climbing Little Mount Peel at the age of 12, Big Mt Peel at the age of 14, Ben Nevis at 15, Ben Lomond at 16 and later a number of other of peaks in the Southern Alps including Mt Cook.[2]

In 1908 he and 1905 All Black Eric Harper were the first to cross the 1899 m high pass in the Southern Alps that now bears his name.[3] In March 1910 with Jack Clarke and Lawrence Earle he made first ascent of the 2,875-metre-high (9,432 ft) Mount D'Archiac in the Southern Alps.[4]

Mitre Peak

Undoubtedly his most famous climb, was the first known ascent of Mitre Peak / Rahotu.[2] While only 1692 metres high, the mountain rises almost sheer from Milford Sound and up until that time was considered to be unclimbable.[2]

In 1911 Dennistoun walked in to Milford Sound from Lake Te Anau over McKinnon Pass, and inquired among the track porters in the hope of finding someone to climb the peak with him. None of the porters had any climbing experience, but one of them, Joe Beaglehole (1875–1962), had read Scrambles among the Alps by noted climber Edward Whymper and was thus chosen by Dennistoun to accompany him.[5]

During a sea voyage in the area with brother George in HMS Pioneer in 1909 Dennistoun had identified what he thought was a possible route but as he wasn't able to reconnoitre it he instead decided to take a route recommended by Donald Sutherland. Sunderland had in 1883 unsuccessfully attempted to climb the peak.

After rowing across in a boat to the mouth of Sinbad Gully at the base of the peak they starting climbing at 7.30am on 13 March 1911.[6][7] Dennistoun and Beaglehole climbed via the south east-ridge through the bush until 300 metres short of the summit Beaglehole decided it was too difficult to continue and stopped. Dennistoun continued on alone up steep, smooth slabs of granite, to reach the summit at 1.15pm.[8]

Descending back down Dennistoun rejoined Beaglehole and they continued with the descent. Unfortunately to avoid climbing back over the Footstool, they decided to descend straight into Sinbad Gully, which meant they had to resort to using a rope to lower themselves down bluffs. They eventually reached the valley floor in darkness, and it soon commenced to rain.[5] With no camping equipment, they had no choice but to continue on until they reached the boat at 9.45pm, cold, wet and exhausted.[8] They then rowed back across to spend the night at the hotel operated by Elizabeth Sunderland.[8]

In 1914 Dennistoun's handkerchief was found in a small cairn on the top of the peak by Jack Murrell (1886–1918) and Edger Williams (1891–1983) when they completed the second ascent of the peak.[9] When J.H. Christie and G. Raymond completed the third ascent in 1941, they found remains of the handkerchief, as well as two halfpennies left by Murrell and Williams.[8]

Antarctica

In 1911 Lieutenant Harry Pennell of the Royal Navy visited Peel Forest station. He was assigned to the research vessel Terra Nova. After having transported the Terra Nova Expedition (1910–1913 ) under the command of British polar explorer Robert Falcon Scott to Cape Evans on the Ross Island in the Antarctic, the ship was wintering over in New Zealand prior to returning with supplies for the expedition. Pennell mentioned that he wanted someone to take charge of the seven Himalayan mules donated by the Indian government which they would be carrying south to the expedition.[10][11] The mules had arrived in September 1911 and were quarantined on Quail Island which is located 3 km from the port of Lyttelton. Pennell could offer no pay, but the adventure was enough to attract Dennistoun and he signed up. While some clothing was provided, Dennistoun had to supply much of his own. As well as caring for the mules Dennistoun was also responsible for 14 Siberian dogs being transported south.[12]

The Terra Nova arrived at Cape Evans on 22 February 1912. After offloading the mules and other supplies Dennistoun returned to New Zealand arriving on 1 April 1912. Instead of being used on a second attempt on the Pole the mules were used later that year to pull the sledges of the search party for Scott. The mules struggled in the harsh environment and all were eventually put down.

For his services to the expedition he received the Polar Medal in silver and the medal of the Royal Geographical Society.[13]

Return to farming

He returned to his farm near Lumsden but eventually sold it in April 1914.

During an expedition in the Southern Alps in January1914 by Dennistoun, his brother George and Sydney King they discovered and named the 2,065-metre-high (6,775 ft) Terra Nova Pass which overlooks the Havelock and Godley Valleys.[14]

In July 1914 he bought yet another farm, this time at Mangamahu, near Whanganui, but his business partner hadn't seen it. When he did eventually see it, he didn't like it. In a panic, Dennistoun tried to get out of the deal as he risked being declared bankrupt and to his relief, he was able to find other partners.

World War I

Following the outbreak of the First World War, Dennistoun travelled as a deckhand on a ship to England where he enlisted. By mid-May in 1915 he was commissioned as a 2nd lieutenant and had joined the North Irish Horse.[15] Arriving in France with his squadron in November, he was immediately promoted to lieutenant. At first he served as an intelligence officer but after a few months was seconded to the Royal Flying Corps, joining the newly-arrived No.23 Squadron as an observer. Another member of the squadron was Dennistoun's cousin, pilot officer Herbert Bainbrigge (Herbie) Russell (1895–1963), and the pair were permitted to fly in the same plane.[15]

Ten days later on 26 June 1916 Dennistoun was observer and bomb thrower in a FE2b biplane being piloted by his cousin, which departed with four other FE2bs on a bombing sortie against the Biache railway junction in Germany.[2] Their aircraft encountered engine problems and they returned to base only for their commanding officer to demand that they take another airplane and continue with the raid. That aircraft was fitted with no bomb racks or sights so there was little chance of hitting the target. Dennistoun was instead instructed to instead throw the bombs over the side by the commanding officer.[2] While flying alone they were attacked near Fampaux by three Fokker Eindeckers. While firing the rear gun Dennistoun was hit three times in the stomach and soon after the main fuel tank was hit and caught fire. Russell despite being shot in the shoulder was able to flatten the aircraft's dive out enough to crash landed near the German trenches, with both being thrown out by the impact with Russell severely burnt. They were captured. Dennistoun was taken to a hospital at nearby Hamblain where he had two operations and appeared to be on the way to recovery. One of the nurses, Lili Eidam, spoke English and wrote a letter dictated by Dennistoun to his mother.[15]

The two airman were reunited at Biache and taken on 5 August to the hospital in the Ohrdruf prisoner of war camp in central Germany. On 9 August Dennistoun's condition deteriorated and he had a third operation. He survived the operation but soon after rapidly declined and he died at 12.05pm the same day.[2] Russell survived his injuries, was repatriated to England in 1918 and later attained the rank of Air Vice-Marshal in the RAF. Dennistoun was first buried at Ohrdruf, before he was reburied after the war in the Niederzwehren Cemetery near Kassel.[16][15]

Legacy

Dennistoun Glacier in Ross Dependency is named after Dennistoun,[17] as is New Zealand's 2,315-metre-high (7,595 ft) Dennistoun Peak,[18] which is located close to the headwaters of the Godley and Havelock Rivers in the Southern Alps. Nearby Dennistoun Pass[19] and Dennistoun Glacier[20] also bear his name.

St Stephen's Church in Peel Forest has a stained glass window donated by Dennistoun's mother, Emily in 1923. It commemorates Dennistoun and his father George. The face of St Michael is a portrait of Dennistoun and in the bottom pane is a small representation of Mitre Peak.

In 1999, Guy Mannering of Geraldine, whose father, also named Guy, was a friend and climbing companion of Dennistoun, compiled and published The Peaks and Passes of JRD, using letters, diaries, photographs and notebook entries held by the Dennistoun family through three generations.

Notes

- "James Robert Dennistoun". Ancestry.com. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- Classen Pages 198, 199, 200, 202, 203, 421

- "Dennistoun Pass". Climb NZ. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- John, Wilson (2 February 2017). "Story: Mountaineering Page 5 – Beyond the central Southern Alps". Te Ara – the Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- Hegg, Danilo (25 April 2015). "Mitre Peak / Rahotu, 1683m". Tramping and Climbing in Aotearoa. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- "First ascents and explorations in the Te Anau – Milford District", The New Zealand Alpine Journal, Berlin: New Zealand Alpine Club, IV (18): 150, 1931

- Hall-Jones (2000), pages 30-31. Dennistoun in his account of the climb in the Otago Witness of 7 February 1912 stated that he climbed Mitre Peak on 13 March 1911. This is now regarded as a mistake was he was descending Mt D'Archiac on this date. An entry on Donald Sunderlands's visitor book states "11-14th March 1911, Barbara and J R Dennistoun, Peel Forest. J.R.D climbed Mitre Peak (first ascent) on 13th taking Joe Beaglehole as far as the long fairly level ridge running into the face of the final peak."

- Hall-Jones (1968), page 167.

- Ede, page 26.

- Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I. 1914, S. xxii.

- Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. II. 1914, S. 372.

- "Quail Island, Lyttelton used by Antarctic expeditions". Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- Kain, Conrad (16 September 2014). Conrad Kain: Letters from a Wandering Mountain Guide, 1906–1933. University of Alberta. ISBN 9781772120042.

- "Long High-Level Journey.", The New Zealand Herald, 2 February 1914, retrieved 23 February 2018

- "Lieutenant James Robert Dennistoun". The North Irish Horse in the Great War. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- "Lieutenant Dennistoun, James Robert". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- "Dennistoun Glacier: Antarctica". Geographic Names. 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- "Dennistoun Peak". NZ Tope Map. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- "Dennistoun Pass". NZ Tope Map. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- "Dennistoun Glacier". NZ Tope Map. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

References

- Classen, Adam (2017). Fearless: The Extraordinary Untold Story of New Zealand's Great War Airmen (Hardback). Auckland, New Zealand: Massey University Press. ISBN 9780994140784.

- Ede, Jock (1988). Mountain Men of Milford (Hardback). Christchurch: Jack Ede. ISBN 0-473-00682-0.

- Hall-Jones, John (1968). Early Fiordland (Hardback). Wellington: A.H. & A.W. Reed.

- Hall-Jones, John (2000). Milford Sound: An Illustrated History of the Sound, the Track and the Road (Hardback). Invercargil: Self-published. ISBN 0-908629-54-0.

- Huxley, Leonard (1913). Scott's Last Expedition (Hardback). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

Further reading

- Mannering, Guy (1999). The Peaks and Passes of J.R.D (James Robert Dennistoun) from the Notebooks, Diaries and Letters from life. Geraldine: JRD Publication. ISBN 0-473-06025-6.

- Strathie, Anne (2015). From Ice Floes to Battlefields – Scott's 'Antarctics' in the First World War. Geraldine: The History Press. ISBN 978-0750961783.

External links

- 'In memoriam – Lieutenant James Robert Dennistoun

- James Robert Dennistoun.

- Mitre Peak / Rahotu, 1683m.

- History Of Scott's Expedition: British Antarctic (Terra Nova) Expedition 1910–1913

- First A-Top Of Mitre Peak. Account in the 12 April 1911 issue of Dominion Post newspaper of Dennistoun's climb of Mitre Peak.

- First Ascent of Mitre Peak. First-hand account by Dennistoun in the 7 February 1912 issue of the Otago Witness of his climb of Mitre Peak.

- The Roll of Honour. Death notice in The Press newspaper for Dennistoun.

- James Robert Dennistoun.