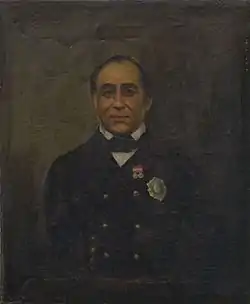

João Maria Ferreira do Amaral

João Maria Ferreira do Amaral (4 March 1803 – 22 August 1849) was a Portuguese military officer and politician. While he was governor of Macau, he was assassinated by several Chinese men, triggering the Battle of Passaleão between Portugal and China.

João Maria Ferreira do Amaral | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| 79th Governor of Macau | |||||||||||

| In office 21 April 1846 – 22 August 1849 | |||||||||||

| Monarch | Mary II | ||||||||||

| Preceded by | José Gregório Pegado | ||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Government Council | ||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||

| Born | 4 March 1803 Lisbon, Portugal | ||||||||||

| Died | 22 August 1849 (aged 46) Macau, Portugal | ||||||||||

| Spouse | Maria Helena de Albuquerque | ||||||||||

| Children | Francisco Joaquim Ferreira do Amaral Joana Teresa de Albuquerque | ||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||

| Allegiance | Portuguese Empire | ||||||||||

| Branch/service | Portuguese Navy | ||||||||||

| Years of service | 1821–1849 | ||||||||||

| Battles/wars | War of Independence of Brazil Liberal Wars Revolt of the Faitiões | ||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 亞馬留 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 亚马留 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Background

João was the first son of Francisco Joaquim Ferreira do Amaral, born in the parish of Alcântara, Lisbon, on 3 May 1773. His father was a descendant from de Macedo, a fidalgo of the Royal Household and a sergeant in the Portuguese Army and the Portuguese Legion during the Napoleonic Wars. His father froze to death during the French Invasion of Russia, where he might have been promoted to alferes, in the winter of 1812. His father was married in Alcântara, Lisbon, on 4 February 1801 to Ana Isabel Cirila de Mendonça. He had two brothers, Joaquim Ferreira do Amaral, born in Alcântara, Lisbon, on 15 October 1804, and Francisca Ferreira do Amaral, born in Alcântara, Lisbon, on 10 May 1805.

Career

João Maria Ferreira do Amaral was a distinguished and valiant officer of the Portuguese Royal Fleet. In 1821, he started his military career as a midshipman in the Brazilian Squadron of the Portuguese Navy posted in Brazil. In 1821, during Brazil's brief war of independence against Portugal, Ferreira do Amaral lost his right arm in the Battle of Itaparica on January 7, 1823.

During the Portuguese Civil War, he was one of the few navy officers that managed to make his way from mainland Portugal to the Terceira island in the Azores, where the Liberal side had established its base. Throughout the war, he served as an officer in the navy of the Portuguese Liberal side. By the end of the war, Ferreira do Amaral was already a high-ranking officer in the Portuguese Navy.

After serving as a deputy governor for Angola, he was appointed the 79th governor of Macau on 21 April 1846. During his three-year tenure as governor, he implemented a range of policies to entrench Portugal's colonial authority over Macau. He unilaterally declared Macau a Portuguese colony, stopped annual rent payments to China, occupied the nearby Island of Taipa (which had never been Portuguese territory), and imposed a new series of taxes on Macau residents.[1]: 81 The Qing authorities in Macau immediately protested against his action and attempted to negotiate. However, beginning in 1849, he expelled all Qing officials from Macau, destroyed the Qing Customs and ceased paying ground rent to the Qing government. In 1851, Amaral led local troops to capture Taipa, an outlying island of the Macau Peninsula.[2]

His actions enraged the Chinese residents further, and he was assassinated on 22 August 1849 by a group of seven Chinese men led by Shen Zhiliang,[3][4] who knocked him off his horse and cut off his head.[5] This was the trigger for the Passaleão incident.

Marriage and issue

Maria Helena de Albuquerque, 1st Baroness of Oliveira Lima (Funchal, São Pedro, 1817 – Lisbon, 6 June 1909), was married to the deceased João Maria Ferreira do Amaral by proxy on 2 October 1849 in Lisbon, Santa Catarina. This marriage took place nearly two months after João Maria Ferreira do Amaral was killed. She did this to legitimize their son Francisco Joaquim Ferreira do Amaral and their daughter Joana Teresa de Albuquerque, Maria Helena de Albuquerque, 1st Baroness of Oliveira Lima (Funchal, São Pedro, 1817 – Lisbon, 6 June 1909). At the time of the marriage, Maria Helena de Albuquerque was unaware that João Maria Ferreira do Amaral was dead.

At that time, Maria Helena was a widow and was taking advantage of the fact that her first husband, António Teixeira Dória, the Lord of the Portuguese colony of Macau, son of Francisco Teixeira Dória and Joana Margarida da Câmara, had died earlier that year. António Teixeira Dória, her first husband, whom she had married in 1836, was a first mate in a navy corvette, whose commander was João Maria Ferreira do Amaral.

According to one of Maria Helena and João Maria’s descendants, Augusto Martins Ferreira do Amaral, 3rd Baron of Oliveira Lima, Maria Helena cheated on her first husband and had an affair with the commander of her first husband’s ship, who was João Maria Ferreira do Amaral. He would later become her second husband. It is also believed that her first son of her first marriage, João Eduardo Teixeira Dória (Lisbon, São Paulo, 13 October 1841), an artillery officer, was also João Maria Ferreira do Amaral's son, for he had similar features. Maria Helena later separated from her first husband and went to live in a convent.

It was during this time that she conceived Francisco Joaquim Ferreira do Amaral, by the ship's commander; although this baby was baptized as son of João Maria Ferreira do Amaral and an unknown mother, to avoid being registered under the name of her first husband.

Legacy

Amaral receives a mixed reception in the former Portuguese colony. While Chinese officials regard him as a symbol of colonialism and national humiliation, the local Macanese community often praises his defense of Macau's autonomy and promotion of free trade with China.[6]

References

- Simpson, Tim (2023). Betting on Macau: Casino Capitalism and China's Consumer Revolution. Globalization and Community series. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-1-5179-0031-1.

- Chan, Ming K. (2003). "Different Roads to Home: The Retrocession of Hong Kong and Macau to Chinese Sovereignty". Journal of Contemporary China. 12 (36): 497. doi:10.1080/10670560305473. ISSN 1067-0564. S2CID 925886.

- Newton, Michael (2014). Famous Assassinations in World History: An Encyclopedia: Volume 1: A-P. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-Clio. p. 150. ISBN 9781610692854. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- Hao, Zhidong (2011). Macau: History and Society. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. p. 148. ISBN 9789888028542. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- Ride, Lindsay; Ride, May (1999). The Voices of Macao Stones. Hong Kong University Press. p. 45. ISBN 9789622094871.

- Yee, Herbert S.; Lo, Sonny S. H. (1991). "Macau in Transition: The Politics of Decolonization". Asian Survey. 31 (10): 911. doi:10.2307/2645063. ISSN 0004-4687. JSTOR 2645063.

- Anuário da Nobreza de Portugal, III, 1985, Tomo II, p. 758 to 761

- GeneAll.net – João Maria Ferreira do Amaral at www.geneall.net João Maria Ferreira do Amaral