Johann Dieter Wassmann

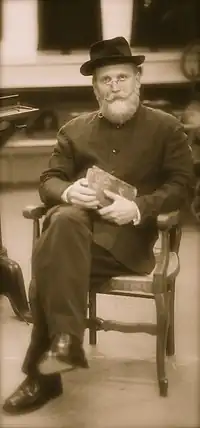

Johann Dieter Wassmann (1841–1898) is a fictitious artist and sewerage engineer, purportedly from Leipzig, Saxony, in east-central Germany. He is the creation of the American-born artist and writer Jeff Wassmann. As a result of the widespread dissemination of his work, Johann Dieter Wassmann is sometimes mistakenly cited as a lesser-known figure among late-19th-century European artists; he is most often identified as an early purveyor of the Dada and Surrealist movements and has become closely associated with several notable artists of the first half of the 20th century, including Kurt Schwitters, Marcel Duchamp, Eugène Atget and Joseph Cornell.[1]

Johann Dieter Wassmann (fictional artist) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | April 2, 1841 |

| Died | March 18, 1898 |

| Nationality | German |

| Education | University of Leipzig |

| Known for | assemblage (art), photography |

| Movement | Dada, Surrealism |

Overview

According to his fictitious biography, Johann Dieter Wassmann was born in Leipzig, where he witnessed the industrial revolution rapidly alter the once agrarian, guild-based and perhaps idealized Electorate of Saxony. In portraying his character as fearful of a less humanitarian world—ill at ease with the changing roles of science, medicine, religion, education, cosmology and time—the artist challenges the viewer to share in the conflicts and anxieties of this ubiquitous thinker.[2] A pivotal event in the author's narrative is Napoleon's defeat at the Battle of Leipzig (1813), recalled first-hand by the character's father. The artist uses Napoleon's rise metaphorically to represent the onslaught of the modern era and his defeat at Leipzig as hope all was not lost of the Romantic era.

The construction of Johann Dieter Wassmann trades heavily on the aesthetic philosopher Samuel Taylor Coleridge's notion of suspension of disbelief to justify the use of certain fantastic or non-realistic elements. Coleridge asserts that if the author can bring a "human interest and a semblance of truth" into a fantastic tale, the reader/viewer will withhold judgement on any improbability that might normally render the story doubtful, a contention the artist is reliant on for his audience to fully engage.[3]

As a sewerage engineer, we see Johann Dieter Wassmann participate in the development of a more modern and scientific approach to the control of infectious disease in cities including Hanover, Göteborg, Dresden, Mexico City and Sydney. As a lecturer at the University of Leipzig, we experience him prompting students to fully explore the creative process, concerned as he is at the decline of liberal education. But Wassmann's lasting legacy is found in his private devotion to his art.[4] (See #Gallery section below.)

Biography

Johann Dieter Wassmann is born into a long line of carpenters on April 2, 1841, the son of August and Maria Wassmann. The youngest of five children to survive into adulthood, he is brought up in the Lutheran creed. After the March Revolutions of 1848, the family flees from Leipzig to Weimar. A bout with rheumatic fever forces Johann to delay the start of his schooling until the age of eight. As a cabinetmaker in Weimar, his father's clients soon include Richard Wagner and Franz Liszt, among others, in what becomes a Grand Tour through 19th-century Germany's music, art, literary and academic elites.[5]

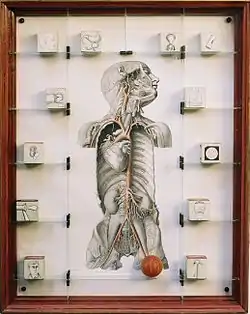

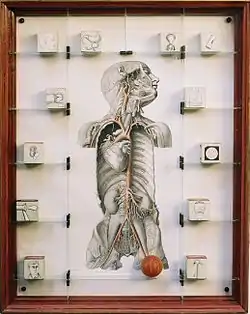

Johann goes on to attend the University of Leipzig before joining an engineering practice, specializing in the emerging field of sewerage management.[6] At 34 he is offered a teaching post in Leipzig. In 1881, six years into his post, Johann sets out to challenge his engineering students through construction of boxed assemblage works enigmatically addressing medical and scientific themes that he feels go unresolved through traditional lecture practices. After an extended display at a Dresden clinic, they become known as the "Dresden Boxes." These works build on the tradition of German wunderkammern and 17th-century Dutch perspective boxes, but display a stripped down aesthetic, precise, but refined.

Through his extensive travels in his private practice, Johann is exposed to the best and worst 19th-century urban development has to offer.[7] His growing angst at what he sees as the encroachment of modernity causes him to begin a second, more personal series of boxes, escaping into a romanticized view of a pre-modern Saxony, much of it set in the ancient wood of Goethe and amidst the hopeful spectre of the American Transcendentalist authors Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. By this point Johann is comfortably married with three children, so the intent of this second stage of boxes is largely private: they are mostly shared with family.

In September 1889, an academic conference in Potsdam brings Johann together with the physicist Max Planck in what results in a seismic shift in Johann's thinking. From here onwards he outright rejects his boxed works of recent years, brandishing them reactionary and "Biedermeier," before moving on to a third and final phase of work, the start of his "early Modern" period.

Johann comes to realize his angst is born not in the modernity of the 19th century, but in the earlier reaches of the Enlightenment he was so recently praising. As the Newtonian perception of a clockwork universe merges with the force of social Darwinism he recognizes that the rising mantra of "progress" has now split the world into two distinct entities: time and space. If he is to return to a unified field of time and space he knows his only choice is not to look back, but to move forward into the modern—into the unknown.

Planck is presenting a paper at the conference on the second law of thermodynamics, the subject of his recent doctoral thesis.[8] The first to call himself a "theoretical" physicist, Planck opens his lecture in Potsdam with the revelation that, "My original decision to devote myself to science was a direct result of the discovery... that the laws of human reasoning coincide with the laws governing the sequences of the impressions we receive from the world around us; that, therefore, pure reasoning can enable man to gain an insight into the mechanism of the world." He concludes by expressing a belief that physical laws allow him to presuppose that the "... outside world is something independent from man, something absolute, and the quest for the laws which apply to this absolute appeared... as the most sublime pursuit in life."[9]

In Planck, Johann discovers a friend and colleague dedicated to the pursuit of a non-Newtonian world-view in which the linear nature of absolute time and space will dissolve into one of a multidimensional universe free of the strictures of past, present and future.[10] Johann's remaining years will be spent expressing these early modern notions through his beloved boxes and an emerging interest in photography.

Planck soon introduces Johann to the writings of Ernst Mach, particularly Analysis of Sensations (1886).[11] Here Johann finds Mach arguing that all knowledge is derived from sensation. Mach credits his philosophical awakening to reading, at age fifteen, his father's copy of Immanuel Kant's Prolegomena to any Future Metaphysics:[12] "The book made at the time a powerful and ineffaceable impression upon me, the like of which I never afterwards experienced in any of my philosophical reading. Some two or three years later the superfluity of the role played by “the thing in itself” abruptly dawned upon me. On a bright summer day in the open air, the world with my ego suddenly appeared to me as one coherent mass of sensations, only more strongly coherent in the ego. Although the actual working out of this thought did not occur until a later period, yet this moment was decisive for my whole view."[13]

All scientific investigation is a result of the experience, or "sensation," of the observer, Mach argues—later a determining factor in the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle. But in the more immediate term, Mach has laid the groundwork for Albert Einstein's special theory of relativity, published in 1905.

Much like Woody Allen's fictional 1920s character Leonard Zelig, Johann Dieter Wassmann finds himself caught up in this cacophony of ideas, theories and movements, allowing him to take an active part in one of the great revolutions of the modern era.

Amongst the cacophony is the advent of photography. Throughout the 1890s, Johann continues to expand the visual vocabulary of his assemblage works, but he also begins to experiment with the latent image, using both a bulky glass-plate view camera, as well as several of the newly developed hand-held roll-film cameras. Over an eight-year period he documents the landscapes, streetscapes, architecture and interiors of eastern Germany, in a style that extends beyond the topographic traditions of the day. These photographic works provide the missing link between the meticulous, but still largely prescriptive street imagery of mid-19th-century photographer Charles Marville,[14] and the lyrical melancholy of Eugène Atget in the early 20th century.[15] As a predecessor to his fellow countrymen Heinrich Zille[16] and August Sander,[17] Johann discreetly anticipates what vast potential the photographic arts holds for the coming age.

Until the modern era catches up with him, that is. On January 6, 1898, Johann slips on ice while boarding a tram in Leipzig; his right leg is crushed, requiring amputation. He dies of a streptococcal infection on March 18, 1898, two weeks shy of his 57th birthday.

The vast trove of artworks Johann has amassed travels to Washington, D.C., with family members in 1910, but remains in storage through two wars with Germany. Only in 1969 is the Wassmann Foundation established, with the works slowly coming to prominence in the years since.[18]

This elaborate fiction allows Johann Dieter Wassmann to escape the conceptual and physical boundaries of the art of his time, making him a pioneer of German modernism, his work emerging as a long lost precursor to the modern art methods and movements we now know as assemblage, collage, installation, Constructivism, Dada and Surrealism.

Historical perspective

%252C_1897_F.jpg.webp)

Johann Dieter Wassmann is part of a long history of artistic pseudonyms and hoaxes. Rrose Sélavy was just one of the pseudonyms used by the artist Marcel Duchamp.[19] In Jeff Wassmann's adopted home of Australia, Ern Malley was the creation of writers James McAuley and Harold Stewart. The 1944 Ern Malley affair, as it is known, remains Australia's most celebrated literary hoax.[20] In the late 1990s, the artist Walid Raad began constructing elaborate fictions chronicling the contemporary history of his native Lebanon, signing his work The Atlas Group and presenting it as a body of collective scholarship.[21] More recently, a New York-based art collective known as the Bruce High Quality Foundation has seen considerable critical and commercial success. In November 2013, a silkscreen by these anonymous artists, "Hooverville," depicting the New York skyline with hobos, was auctioned for $425,000 at Sotheby's New York.[22]

In an artistic intervention known as culture jamming, Wassmann has also intertwined his work with contemporary literary conceits. In 2006, Rohan Kriwaczek created a sensation with his publication of An Incomplete History of the Art of the Funerary Violin (Overlook Press), which purported to trace the lost history of the funerary violin. Shortly before publication, the book was exposed to the New York Times as a hoax by a book buyer at Prairie Lights Books in Iowa City, Iowa.[23] Wassmann stepped in to confuse matters further by using an additional character, a German curator, to defend Kriwaczek in online literary blogs and discussion pages, claiming that as a child in Leipzig, August Wassmann (the character's father) had known one of the funerary violinists Kriwaczek cites, further proof of the funerary violin. Wassmann had been sent an advance copy of the book by the owner of Prairie Lights Books, Jim Harris, allowing him to comment with apparent authority on the book's contents prior to publication.[24]

Legacy and influence

The character of Johann Dieter Wassmann was launched under the supposed auspices of the fictitious Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C., in the solo exhibition Bleeding Napoleon at the Melbourne International Arts Festival 2003.[25] Since that time, the artist has created a rival institution vying to have the works of Johann Dieter Wassmann repatriated to Germany: MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.[26]

In the United States, Johann Dieter Wassmann is best known through a long-running Google Adwords campaign in the New York Times. The ads, with politically charged entendres such as The Wassmann Foundation – art & philanthropy – forging a better tomorrow, have received over nineteen million page-views in the newspaper's online Arts section. Art in America's Washington, D.C., correspondent, James Mahoney, has written,

Such visionaries as Herr Wassmann will not only endure, they will prevail, I'm more than certain.

As the Wassmann Foundation and related characters have evolved, the project has come to function on three distinct levels. Firstly, the artist endeavours to scrutinise the ever-increasing presence of artist, curator and art institution alike, as brands. In establishing his own artist, curators and institutions as wholly fictitious, the contemporary artist is free to explore these roles as pure brand, existent for no other purpose than critical assessment.

Secondly, the artist argues that the unresolved angst of our current age is the culmination of the mistakes of modernity. We catch a glimpse of this angst, as expressed by the sewerage engineer protagonist, before losing clarity to the mounting failures of the 20th and now 21st-centuries, distorting our anxieties beyond recognition.[27]

Lastly, on a third level, the project points up a certain paradox created by the proliferation of the worldwide-web: in a mass society, the individual grows in importance, rather than diminishes.

For artists and individuals in what were formerly the planet's outer reaches, Wassmann has seen the web democratize access to the structures and machinations of power to an extent previously unimagined. He contends that little more than 25 years after the art world discovered there was an outside and a periphery, they suddenly find it is gone. In a postcolonial/internet age, there is only the center to be fought over and for the artist, the ensuing chaos to decipher. Where once the internet merely informed the political process, Wassmann has argued that the internet would, and now has developed the immense capability of wholly transforming political process. While projects such as Wassmann's function on a relatively benign level, he believes the realigned power structures they allude to allow individuals outside the arts to masterfully, and often frighteningly, alter the real world irretrievably.[28]

Gallery

Assemblage boxes

Arteriae Pelvis, Abdomimis, et Pectoris, 1883. 70 x 55.5 x 8 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.

Arteriae Pelvis, Abdomimis, et Pectoris, 1883. 70 x 55.5 x 8 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig. Foucault’s Pendulum, 1884. 36 x 18.5 x 9 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.

Foucault’s Pendulum, 1884. 36 x 18.5 x 9 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig. The Case of the City of London, 1894. 39.5 x 29.5 x 26 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.

The Case of the City of London, 1894. 39.5 x 29.5 x 26 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig. L'Hotel de Vie, 1886. 52 x 70 x 15.5 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.

L'Hotel de Vie, 1886. 52 x 70 x 15.5 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig. Phrenology of the Brain, 1895. 36 x 30.5 x 9 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.

Phrenology of the Brain, 1895. 36 x 30.5 x 9 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig. Trephining of the Skull, 1895. 36 x 30.5 x 9 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.

Trephining of the Skull, 1895. 36 x 30.5 x 9 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig. Harmonisch, 1895. 14.5 x 14.5 x 7 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.

Harmonisch, 1895. 14.5 x 14.5 x 7 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig. Prince Otto von Bismarck, 1896. 66 x 53 x 13 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.

Prince Otto von Bismarck, 1896. 66 x 53 x 13 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig. 16969, 1896. 38 x 28 x 10 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.

16969, 1896. 38 x 28 x 10 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig. Appareil Auditif, 1896. 46 x 35 x 10 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.

Appareil Auditif, 1896. 46 x 35 x 10 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig. L’Hotel des Spheres, 1896. 80 x 49 x 24 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.

L’Hotel des Spheres, 1896. 80 x 49 x 24 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig. Nebula, 1896. 17.5 x 17 x 11 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.

Nebula, 1896. 17.5 x 17 x 11 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig. Nietzsche, 306P, 1897. 38 x 28 x 10 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.

Nietzsche, 306P, 1897. 38 x 28 x 10 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.%252C_1897_F.jpg.webp) Dasein (Being), 1897. 48 x 26 x 7 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.

Dasein (Being), 1897. 48 x 26 x 7 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.%252C_1897_F.jpg.webp) Ehepaar (Married Couple), 1897. 30.5 x 25 x 5.5 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.

Ehepaar (Married Couple), 1897. 30.5 x 25 x 5.5 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.%252C_1897_F.jpg.webp) Vorwärts! (Go Forward!), 1897. 57.5 x 31 x 9.5 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.

Vorwärts! (Go Forward!), 1897. 57.5 x 31 x 9.5 cm. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.

Photography

Freundschaftstempel, Potsdam, 1896. Albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm. The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C.

Freundschaftstempel, Potsdam, 1896. Albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm. The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C. 1000 Oaks, 1897. Albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm. The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C.

1000 Oaks, 1897. Albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm. The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C. Berlin, 1897. Albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm. The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C.

Berlin, 1897. Albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm. The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C. Freyburg, 1897. Albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm. The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C.

Freyburg, 1897. Albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm. The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C. Nikolaikirche, Leipzig, 1894. Albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm. The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C.

Nikolaikirche, Leipzig, 1894. Albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm. The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C. Quedlinburg, 1897. Albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm. The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C.

Quedlinburg, 1897. Albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm. The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C. Schloss Sanssouci, Potsdam, 1896. Albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm. The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C.

Schloss Sanssouci, Potsdam, 1896. Albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm. The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C. Weinbergterrassen, Park Sanssouci, Potsdam, 1897. Albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm. The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C.

Weinbergterrassen, Park Sanssouci, Potsdam, 1897. Albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm. The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C.

Ephemera

Worn apothecare print. French, 1870s. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.

Worn apothecare print. French, 1870s. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig. Biedermeier snuff box. German, 1840s. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.

Biedermeier snuff box. German, 1840s. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig. Envelope to Anna Peterson. Swedish, 1890s. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.

Envelope to Anna Peterson. Swedish, 1890s. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig. Family death notice. Swedish, 1890s. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.

Family death notice. Swedish, 1890s. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig.

References

- Negrini, Paolo. Network Map of Knowledge and Art Retrieved April 30, 2012

- Wassmann Foundation Retrieved October 10, 2014

- Tomko, Michael. "Politics, Performance, and Coleridge's 'Suspension of Disbelief'," Victorian Studies, Volume 49, Number 2, Winter 2007. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- Crawford, Ashley. "Hoax most perfect," Melbourne Age, October 11, 2003. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- Stombock, M. "A Carpenter's Tale" MuseumZeitraum Leipzig. Retrieved October 19, 2014

- Seeger, H. "The history of German waste water treatment," European Water Management, Volume 2, Number 5, 1999, pp. 51-56. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- Sorensen, S. (et al). "Historical overview of the Copenhagen sewerage system," Water Practice & Technology, Volume 1, Number 1. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- "Max Planck - Biographical Nobel Lectures, Physics 1901-1921," Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam, 1967. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- "Who was Max Planck?" European Space Agency. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- Minkowski, Hermann (1909), , Physikalische Zeitschrift, 10: 75–88

- Various English translations on Wikisource: Space and Time.

- Mach, Ernst. The Analysis of Sensations (1886), William, C.M. (trans.), Chicago: The Open Court Publishing Company, 1914. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- Kant, Immanuel. Prolegomena to any Future Metaphysics (1783), Carus, Dr. Paul (trans.), Chicago: The Open Court Publishing Company, 1912. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- Pojman, Paul. "Ernst Mach", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2011 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.). Retrieved October 20, 2014

- Kimmelman, Michael. "Glimpsing a Lost Paris, Before Gentrification," New York Times, March 9, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- Grundberg, Andy. "Photography View; Eugene Atget—His art bridged two centuries," New York Times, March 10, 1985. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- Kimmelman, Michael. "Lively Eye on Old Berlin: Wonderful Life, Ja?" New York Times, March 27, 2008. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- Kimmelman, Michael. "Preserving an Era Image by Image," New York Times, June 4, 2004. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- Vogt, S. "Bleeding Napoleon-The Art of Johann Dieter Wassmann" Wassmann Foundation. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- Fair, S.S. "Gaga for Dada," New York Times, September 25, 2005. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- Pierce, Peter. McAuley, James Phillip (1917-1976), Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 15 (MUP), 2000. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- Smith, Roberta. "Mixing Fact and Fiction to Open Up Larger Reality,' New York Times, March 4, 2006. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- Sotheby's sale, 13 November 2013 Sotheby's. Retrieved September 5, 2014.

- Bosman, Julie. "British Author Espies a Funerary Violin Vacuum and So Fills It," New York Times, October 4, 2006. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- "Tonight: McNally Robinson's, Halloween, Funerary Violin & Rohan Kriwaczek," Overlook Press blog, October 31, 2006. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- "Best of the fest," Melbourne Age, October 5, 2003. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- Blouin "Early Modern Works Returning to Germany," ArtInfo, Nov. 1, 2007. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- Rose, Gideon (ed.), "How We Got Here—The Rise of the Modern Order," Foreign Affairs, January/February 2012. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- Wright, Lawrence. "The Terror Web: Were the Madrid bombings part of a new, far-reaching jihad being plotted on the Internet?" New Yorker, August 2, 2004. Retrieved September 24, 2014.