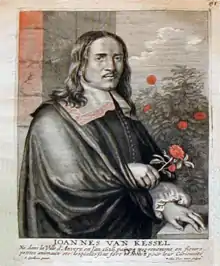

Jan van Kessel the Elder

Jan van Kessel the Elder or Jan van Kessel (I) (baptized 5 April 1626, Antwerp – 17 April 1679, Antwerp) was a Flemish painter active in Antwerp in the mid 17th century. A versatile artist he practised in many genres including studies of insects, floral still lifes, marines, river landscapes, paradise landscapes, allegorical compositions, scenes with animals and genre scenes.[1] A scion of the Brueghel family many of his subjects took inspiration of the work of his grandfather Jan Brueghel the Elder as well as from the earlier generation of Flemish painters such as Daniel Seghers, Joris Hoefnagel and Frans Snyders.[2] Van Kessel’s works were highly prized by his contemporaries and were collected by skilled artisans, wealthy merchants, nobles and foreign luminaries throughout Europe.[3]

_-_Garden_and_house_spiders_with_grass_snakes_and_caterpillars_contorted_and_entwined_to_spell_the_artist's_name.jpg.webp)

Life

Jan van Kessel the Elder was born in Antwerp as the son of Hieronymus van Kessel the Younger and Paschasia Brueghel (the daughter of Jan Brueghel the Elder). He was thus Jan Brueghel the Elder's grandson, Pieter Bruegel the Elder's great-grandson and the nephew of Jan Brueghel the Younger. His direct ancestors in the van Kessel family line were his grandfather Hieronymus van Kessel the Elder and his father Hieronymus van Kessel the Younger, who were both painters. Very little is known about the work of these van Kessel ancestors.[4]

_-_A_sprig_of_redcurrants_with_an_elephant_hawk_moth%252C_a_ladybird%252C_a_millipede_and_other_insects.jpg.webp)

At the age of only 9, Jan van Kessel was sent to study with the history painter Simon de Vos.[4] He further trained with family members who were artists. He was a pupil of his father and his uncle Jan Brueghel the Younger.[1]

In 1644 he became a member of the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke where he was recorded as a "blomschilder" (flower painter).[1] He married Maria van Apshoven on 11 June 1646. The couple had 13 children of whom two, Jan and Ferdinand, were trained by him and became successful painters. He was captain of a local schutterij (civil guard) in Antwerp.[4]

Jan van Kessel was financially successful as his works commanded high prices and were widely collected at home and throughout Europe.[3][5] He bought in 1656 a house called the Witte en Roode Roos (White and Red Rose) in central Antwerp. By the time his wife died in 1678 his fortune seems to have turned for the worse. In 1679 he had to mortgage his house. He had become too ill to paint and died on 17 April 1679 in Antwerp.[4]

He trained other painters and also his own family members. His pupils included his sons Jan and Ferdinand.[1]

Work

General

Jan van Kessel the Elder was a versatile artist who practised in many genres including studies of insects, floral still lifes, marines, river landscapes, paradise landscapes, allegorical compositions, scenes with animals and genre scenes.[1] His dated works range from 1648 to 1676.[6]

_-_A_River_Landscape_with_Figures_on_a_Track.jpg.webp)

Attribution of work to Jan van Kessel the Elder has been difficult due to confusion with other artists with a similar name all active around the same time. In addition to his son Jan, there was another Antwerp painter with the name Jan van Kessel (referred to as 'the other' Jan van Kessel) who painted still lifes, while in Amsterdam there was a Jan van Kessel known as a landscape painter. To complicate things further, while he is usually referred to as Jan van Kessel I since he had an uncle also called Jan van Kessel he is sometimes referred to as Jan van Kessel II and his son Jan van Kessel the Younger as Jan van Kessel III.[7][8][9] Another problem for attributions has been the fact that Jan van Kessel the Elder used two different styles of signature on his work. He used a cursive, more decorative signature for larger formats, which would have been difficult to read in a smaller painting. This practice lead to the erroneous assumption that these works were made by two different painters.[2]

Jan van Kessel specialized in small-scale pictures of subjects gleaned from the natural world such as floral still lifes and allegorical series showing animal kingdoms, the four elements, the senses, or the parts of the world. Obsessed with picturesque detail, van Kessel worked from nature and used illustrated scientific texts as sources for filling his pictures with objects represented with almost scientific accuracy.[10]

Nature studies

Jan van Kessel produced a great number of studies of animals such as insects, caterpillars and reptiles as well as images of flowers and rare objects from all over the known world.[11] He showed himself to be a keen observer and his animal studies were praised in his day for their meticulousness and precision.[5] His work in this field reflects the contemporary worldview in which the appreciation of art and nature went hand in hand. That same desire to collect and categorize the natural world, which had given impetus to the creation of the Kunstkammern and Wunderkammern in the late 16th and 17th century, inspired the artists of the day to achieve the same in painted form.[11] Jan van Kessel's grandfather Jan Brueghel the Elder had already demonstrated in his work how artists, starting from empirical observation, could represent the world through ordering and classifying its many elements.[12]

An important influence on his animal studies was the scientific naturalism of the Flemish artist Joris Hoefnagel known primarily for his illuminated manuscripts and still lifes on vellum. Hoefnagel's studies of flowers and insects were engraved and published under the title Archetypa studiaque patris Georgii Hoefnagelii by his son Jacob Hoefnagel in 1592 in Frankfurt. The book is a collection of 48 engravings of plants, insects and small animals shown ad vivum made after studies by Joris Hoefnagel and was very influential on next generations of animal painters.[13]

Van Kessel's animal studies distinguish themselves from the dispassionate approach of his predecessors, who arranged the various flora and fauna in rows, as if they were specimens in a collector’s cabinet. Van Kessel put greater emphasis on composition and aesthetic without abandoning an accurate depiction of the individual creature in question. An example of this approach is the work A still life study of insects on a sprig of rosemary with butterflies, a bumble bee, beetles and other insects (Sotheby's 10 November 2014, New York, lot 31). In this composition van Kessel created a dynamic arrangement with insects around a single sprig of rosemary, which gives the illusion that the butterflies and bee are conversing. Despite the absence of a moralizing text, as found in the Archetypa of Hoefnagel, van Kessel's message of nature as a mirror of God’s power would have been clear to his audience.[11][14]

His studies of flora and fauna were often executed in large sets and occasionally served as the drawer fronts of collector's cabinets that were used for displaying objects in Wunderkammern. Unlike the dried and pinned samples stored within these cabinets, van Kessel’s painted subjects appear very much alive and are clearly intended to surprise and delight the viewer upon opening the outer doors.[11] Jan van Kessel started painting these works in the first half of the 1650s and the earliest dated examples were painted in 1653. While some of these works were executed on panel, the majority were painted on copper. Copper provided the smooth surface best suited to his meticulous and detailed finish.[14]

The four continents

Jan van Kessel created two series of allegorical paintings representing the Four parts of the world or the Four continents. These series dating to the 1660s were composed of four composite pictures made up of 16 miniature oil paintings on copper plates that are arranged around a larger painting, also on copper, and mounted into a compartmentalized ebony cabinet. The centerpieces represent the continents of Europe, Asia, Africa and America through a myriad of figures in ethnic dress and exotic animals. The surrounding plates depict separate cities and geographic areas in which supposedly native flora and fauna are shown.[3]

The first series in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich is complete unlike the second one which is in the Museo del Prado in Madrid of which a few panels are missing. A description that was made of the work in Spain is evidence that the two series were identical in format. The cabinets in which the series are mounted were a specialty of Antwerp and one of its important luxury good exports. They were made from expensive, exotic woods. Their fronts were divided into multiple compartments. It has been argued that van Kessel created a new type of pictorial type in his series of The four parts of the world by inverting the hierarchy of the materials that make up the cabinet object by elevating the importance of the paintings over the furniture in which they are embedded.[3]

Between 1650 and 1675 van Kessel produced more than 300 paintings on small copper plates, many of which were used for the decoration of cabinets. Where the paintings placed in cabinets were traditionally low quality workshop products, van Kessel's The four parts of the world consists of highly individualised works of high artistic achievement which could be admired in their own right. As objects that depict treasures from different parts of the world and are themselves composed of materials from faraway places, van Kessel's pictures of the continents would have held particular significance for his elite audience of artisans, merchants, connoisseurs and foreign dignitaries. Van Kessel's The four parts of the world is known to have been appreciated by contemporary viewers as a demonstration of his artistic skill and virtuosity, which were qualities that were highly prized by collectors.

The pictorial theme of the four parts of the world had emerged in Antwerp’s humanist circles around 1570. It appeared originally in allegorical prints, book publications and pageantry decorations.[3] The theme's great popularity can be understood by contemporary scientific interests.[15] The theme had migrated to painting by the early 17th century.

Stylistically, van Kessel's views imitate the miniaturist manner of his grandfather Jan Brueghel the Elder. All of the pictures follow a similar same compositional scheme: a view of a city is seen in the background while a close-up of large animals of various species makes up the foreground. This scheme was characteristic for 16th-century graphic artists such as Joris Hoefnagel and Adriaen Collaert, who are known to have been a source of inspiration for Van Kessel's work more generally. This arrangement seems inspired by the cartography of the time, where the maps of the continents are illustrated with a multitude of animals, real and fantastic, and surrounded by borders divided into small scenes with the representation of the planets, the seasons of the year and the four elements, or maps of countries bordered by small vignettes with views of the most important cities. Joris Hoefnagel and Adriaen Collaert were also the direct source for some of the animals painted by van Kessel. Others are copied from paintings by Jan Brueghel the Elder, Jan Fyt, Frans Snyders, Paul de Vos and Rubens.

Despite their naturalism, the inclusion in the pictures of fantastic animals and beings seems to indicate that the painter did not entirely seek an objective or scientific description but a representation of the exotic as such.[15]

Garland paintings

_and_David_Teniers_(II)_(attributed_to)_-_Soap_bubbles%252C_allegory_of_Vanitas.jpg.webp)

Van Kessel's grandfather Jan Brueghel the Elder played a key role in the invention and development of the genre of garland paintings in the first two decades of the 17th century. Garland paintings typically show a flower garland around a devotional image or portrait.[16] Other artists involved in the early development of the genre included Hendrick van Balen, Andries Daniels, Peter Paul Rubens and Daniel Seghers. The genre was initially connected to the visual imagery of the Counter-Reformation movement.[17] The genre was further inspired by the cult of veneration and devotion to Mary prevalent at the Habsburg court (then the rulers over the Southern Netherlands) and in Antwerp generally. The earliest specimens of the genre often include a devotional image of Mary in the cartouche but in later examples the image in the cartouche could be religious as well as secular.[16][17]

Garland paintings were usually collaborations between a still life and a figure painter. Van Kessel would typically paint the surrounding still life while a figure painter was responsible for the figure or other image in the cartouche. His collaborators on garland paintings are believed to have included his uncle David Teniers the Younger, Erasmus Quellinus the Elder, Hendrick van Balen the Elder, Thomas Willeboirts Bosschaert and possibly Jan Boeckhorst.

An example of a collaborative garland painting made by Jan van Kessel and David Teniers the Younger is the composition The soap bubbles (c. 1660-1670, Louvre). In this work Jan van Kessel painted a decorative garland representing the four elements around a cartouche showing a young man blowing soap bubbles, which symbolizes vanity, i.e. the transience of life.[18]

Other collaborations

Van Kessel collaborated on a series of twenty copper panels commissioned by two members of the Moncada family, a noble Catalan family. The panels illustrate the deeds of Guillermo Ramón Moncada and Antonio Moncada, two brothers from the Moncada House who lived at the end of the 14th and beginning of the 15th century in Sicily. Five prominent Flemish artists collaborated on the panels. Of 12 scenes devoted to Guillermo Ramón Moncada, Willem van Herp painted six, Luigi Primo five and Adam Frans van der Meulen one. Van Kessel's uncle David Teniers the Younger was responsible for all eight panels describing the deeds of Antonio Moncada. These were painted not long after the first part of the series had been finished. Jan van Kessel created the decorative borders framing each episode.[19]

Gallery

- Selected works

_-_Still_life_of_fish_in_a_harbor_landscape%252C_possibly_an_allegory_of_the_element_of_water.jpg.webp) Still life of fish in a harbor landscape, possibly an allegory of the element of water

Still life of fish in a harbor landscape, possibly an allegory of the element of water.jpg.webp) Allegory of air

Allegory of air_-_Venus_at_the_Forge_of_Vulcan_-_WGA12152.jpg.webp) Venus at the forge of Vulcan

Venus at the forge of Vulcan A still life of flowers, a lizard and insects

A still life of flowers, a lizard and insects Masques made with seashells

Masques made with seashells The submission of the Sicilian rebels to Antonio de Moncada in 1411

The submission of the Sicilian rebels to Antonio de Moncada in 1411

Brueghel family tree

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Jan van Kessel (I) at the Netherlands Institute for Art History (in Dutch)

- W. Laureyssens. "Kessel, van." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 17 January 2017

- Nadia Groeneveld-Baadj, A World of Materials in a Cabinet without Drawers: Re-framing Jan van Kessels The Four Parts of the World', in: Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art/Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek 62: Meaning in Materials, pp. 202-237, 2013

- Frans Jozef Peter Van den Branden, Geschiedenis der Antwerpsche schilderschool, Antwerp, 1883, pp. 1098–1101 (in Dutch)

- Johannes van Kessel in Cornelis de Bie, Het Gulden Cabinet, 1662, page 409

- Jan van Kessel (Antwerp 1626-1679), Grapes, peaches, cranberries, flowers and butterflies, in a porcelain bowl on a wooden ledge; and Grapes, blackberries, cherries, butterflies and a walnut in a porcelain bowl on a wooden ledge at Christie's

- Jan van Kessel the Younger at the Netherlands Institute for Art History (in Dutch)

- 'the other' Jan van Kessel at the Netherlands Institute for Art History (in Dutch)

- Jan van Kessel (of Amsterdam) at the Netherlands Institute for Art History (in Dutch)

- Jan van Kessel (Antwerp 1626-1679), Roses, tulips, an iris and other flowers, in a glass vase on a stone plinth, with butterflies and other insects at Christie's

- Jan van Kessel (I), A still life study of insects on a sprig of rosemary with butterflies, a bumble bee, beetles and other insects at Sotheby's

- Arianne Faber Kolb, Jan Brueghel the Elder: The Entry of the Animals into Noah’s Ark, Getty Publications, 2005, p. 47

- The Archetypa studiaque patris Georgii Hoefnagelii at archive.org

- Jan van Kessel, Study of insects, butterflies and a snail with a sprig of forget-me-nots; study of butterflies and other insects with a sprig of apple blossom at Sotheby's

- Posada Kubissa, T., El paisaje nórdico en el Prado: Rubens, Brueghel, Lorena, 2012, pp. 129-130 (in Spanish)

- Susan Merriam, Seventeenth-Century Flemish Garland Paintings. Still Life, Vision and the Devotional Image, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2012

- David Freedberg, "The Origins and Rise of the Flemish Madonnas in Flower Garlands, Decoration and Devotion", Münchener Jahrbuch der bildenden Kunst, xxxii, 1981, pp. 115–150.

- Jan van KESSEL, Les Bulles de savon at the Louvre (in French)

- David Teniers II and Jan van Kessel I, The Submission of the Sicilian Rebels to Antonio de Moncada in 1411 at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection

External links

Media related to Jan van Kessel the Elder at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Jan van Kessel the Elder at Wikimedia Commons Media related to Paintings of insects and flowers by Jan van Kessel the Elder at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Paintings of insects and flowers by Jan van Kessel the Elder at Wikimedia Commons