John Bradby Blake

John Bradby Blake (4 November 1745 – 16 November 1773) was an English botanist. Working in China as a resident supercargo for the British East India Company, he sent seeds of local plants to Britain and the American colonies for propagation while also recording and studying Chinese plants and culture. Though he died at the age of 27, Bradby Blake left behind a rich archive of his work and correspondence that gives insight into cross-cultural interactions and botanical study in China at the time.[1]

John Bradby Blake | |

|---|---|

A watercolor portrait of John Bradby Blake, likely painted by Simon Beauvais in 1774.[1] | |

| Born | November 4, 1745 Westminster, London, England |

| Died | November 16, 1773 (aged 28) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Botany |

Family

John Bradby Blake was the son of Captain John Blake (b. 1713) and his wife Mary. John Blake, like his father (John Bradby Blake's grandfather), was a ship's captain.[2] At the age of 20, he sailed for southeast Asia with the East India Company ship the Halifax, serving as second mate. John Blake sailed with the Halifax again on the ship's next voyage; this voyage was his first as a captain. Through voyages with the East India Company and through command of private vessels in Asia, Captain Blake became a wealthy man. From the 1760s he was also manager of a business transporting fresh fish to a market in Westminster, an attempt to circumvent the monopoly of the fishmonger's company, although ultimately stepped away from that project due to financial difficulties.[1]

He married Mary Tymewell (b. 1723) on 17 November 1743. Of the couple's 12 children, only three (John Bradby Blake and two sisters) would survive beyond the age of two.[1]

While John Bradby Blake was working in Canton (Guangzhou) and Macao, Captain Blake was an essential part of his son's international botanical network. Involved in the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, Captain Blake connected John Bradby Blake's shipments of seeds and other botanical materials with botanists and merchants around the world. This included correspondence with John Ellis, whose designs for transporting live plants across the ocean are very similar to John Bradby Blake's, and Henry Laurens, a future signer of the American Declaration of Independence.[1][3][4] It was also Captain John Blake who, with the help of Whang-y-Tong (also called Whang at Tong, Whang Atong, and Whang Yadong), compiled an archive of Bradby Blake's work and correspondence after his death.[1][3][5][6] As well as their botanical interests, the Blakes were also involved to a degree in predatory lending practices based around the tea trade, something that led ultimately to a minor financial crisis and Britain's first embassy to China.[7]

Life

John Bradby Blake was born in Westminster, London. John Bradby Blake was educated at Westminster School. His academic studies at that time would have consisted primarily of Latin, Greek, and biblical study. He likely learned botany from his father and may have also been influenced by the numerous plant nurseries that were located in the part of London where Bradby Blake grew up; wherever Bradby Blake learned botany, it was probably not at Westminster School. On 29 August 1764, Bradby Blake applied for the position of either writer or junior supercargo with the British East India Company, following in his father's footsteps. Though the Company did not accept his first application, Bradby Blake applied again on 27 August 1766. This time he was successful, and later that year Bradby Blake travelled to Canton (present-day Guangzhou) in China as a supercargo of the East India Company. Following a brief return to London in 1768, Bradby Blake sailed again for China, this time as a resident supercargo. Staying in Macao in between trading seasons, Bradby Blake would spend the remainder of his short life in Asia.[8]

He devoted his spare time in Canton to natural science, particularly botany, as well as some attempts to record and study Chinese language and culture.[1][9] His plan was to procure the seeds of commercially useful plants found in China and to send to Europe and the Americas these seeds and the plants producing them. His idea was that they might be propagated in Great Britain and Ireland as well as in the British colonies.[10] As discussed further below, Blake's scheme was in many ways successful. Cochinchina rice was grown in Jamaica and South Carolina; the tallow-tree prospered in Jamaica, Carolina, and in other American colonies;[11] and many of the plants he sent to Britain were also raised in several botanical gardens near London. He also sent to England some specimens of fossils and ores.[10]

He fell ill and died in Canton on 16 November 1773, aged 28. He was unmarried. A proposal for Blake's membership of the Royal Society, made in February 1774, was withdrawn when news of his death became known.[8]

Work and legacy

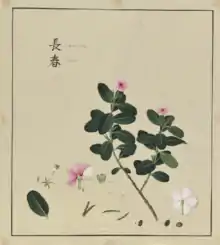

When not working as resident supercargo for the East India Company in China, Bradby Blake was devoting his time to botany and horticulture, as well as some study of Chinese language and culture. His goals were several: first, to cultivate and ship commercially viable plants back to Europe and beyond and, second, to "form a Compleat Chinensis of Drawings copied from Nature, with a Collection of Specimens, Plants, Seeds, etc., etc., with every necessary description relative to their Uses, Virtues, Culture, Seasons, Parts of Fructification, [and] when in bloom."[1] As well as these larger projects, Bradby Blake engaged in the creation of an English-Chinese dictionary, in which Chinese characters are accompanied by illustrations, English phonetic spellings, and English translations.[9] It is important to note that all of Bradby Blake's artistic endeavors were undertaken with the help of Chinese artists and interlocutors, namely Whang-y-Tong and an artist known as Mauk-Sow-U (also called Mai Xiu), making the existing record of his work the result of an international and cross-cultural collaboration.[12] Mauk-Sow-U was likely hired from one of the factories that made Canton export art, a style of painting that provided European sailors with paintings of Asia to take home as souvenirs. The style of the work in the John Bradby Blake archive, however, is markedly different from the style of export art, indicating the botanical focus towards which Bradby Blake steered the project and the skill of Mauk-Sow-U and any other collaborators.[3]

Botanical shipments

Connected with his father, Captain John Blake, in London (and, through Captain Blake, other merchants and botanists around the world), Bradby Blake was responsible for the introduction of a variety of Chinese plants into North America and the Caribbean. Captain John Blake and John Ellis were essential parts of Bradby Blake's botanical shipping operation. While Bradby Blake himself experimented with the best ways to grow, package, and transport seeds and specimens of tallow, turmeric, camellia and other southeast Asian plants, his London counterparts ensured that his shipments reached the broader world. The Americas were most often the destination, as the British saw the New World colonies as having the ideal climate to support valuable Asian plants. While trade was flourishing before the mid-1700s, the American Revolutionary War put up considerable barriers to this intercontinental botanical exchange.[11][13][14]

Although many plants were sent to the colonies in the New World, specimens were distributed to the flourishing nurseries and gardens around London and in other cities as well as the Royal Gardens at Kew and the Chelsea Physic Garden (two well-known centers for botanical knowledge). John Bradby Blake in fact grew up in Westminster, a neighborhood in London well-known for its many nurseries, and these nurseries may have been an early influence that led to his interest in botany. The fact that shipments went to smaller, commercial nurseries as well as the more prestigious botanic gardens signifies the importance of these less well-documented nurseries and also the many avenues of communication and trade within the botanic community.[15]

Bradby Blake spent considerable time and energy experimenting with various ways to send seeds and plants overseas. For example, with the tallow tree, Bradby Blake tested growing seeds in various types of soil and with varying amounts of water. He also tested and recorded various treatments to preserve seeds; these included storage in a tortoiseshell box, storage in wax, and drying the seeds before later packaging and shipping them. For live plants, Bradby Blake ultimately utilized a method of transport similar to one designed by John Ellis, in which plants are kept in wired cases that held them stable while also allowing for efficient movement of the specimens.[3]

A "Compleat Chinensis"

While experimenting with methods of packaging and transport, Bradby Blake hired Mauk-Sow-U to create a comprehensive record of Chinese plants, what Bradby Blake also called a "Compleat Chinensis." Whang-y-Tong was also involved in this project, as a translator and interlocutor. Because the Chinese government at the time limited European visitors to Canton (Guangzhou) during the trading season and Macao for the rest of the year, Bradby Blake was largely limited in what plants he could acquire. As a result, many of the plants and all of the animals that Bradby Blake and Mauk-Sow-U depicted were species that could be acquired in the markets of those two cities. These materials now act as a record that allows scholars to reconstruct the plants grown in Chinese gardens at the time, particularly those of the Hong merchants, the powerful trade group that dominated the Canton trade era.[16]

Today, the existing archive of John Bradby Blake's work consists predominately of this unfinished Chinese flora, created as watercolor and gouache paintings. While there are some depicting fish and one of a turtle, the vast majority of the illustrations are of plants. Bradby Blake and Mauk-Sow-U emphasized various botanical details in the illustrations, including the detailed anatomy of flowers, various stages of development, and even the relationship between figs and fig wasps. While not as elegant as the paintings of the contemporary Georg Dionysius Ehret, of whose work with Linnaeus on taxonomy Bradby Blake was likely aware, the Bradby Blake-commissioned paintings are just as scientifically detailed.[3][12][17]

The dictionary

A third part of Bradby Blake's legacy involves a Chinese/English dictionary, a written and illustrated document that translates various aspects of Chinese culture into English. The dictionary was likely a means for Bradby Blake to learn and study Chinese language and culture and was created with the help of several Chinese writers and illustrators. The dictionary entries are always organized in the same way: first, there is always an accompanying illustration of the item, thing or concept; second, there are neatly drawn Cantonese characters to accompany the illustration; third, there are Cantonese pronunciations written out using English letters; finally, these materials are accompanied by definitions, translations, or explanations in English. The writer of the English text (likely Bradby Blake) often demystifies various components of Chinese culture. For example, on the entry for "Dragon," he adds the qualifier "imaginary." Similarly, for later entries of players depicting various figures in Chinese mythology and folklore, the English translation does not translate the mythological significance of these figures, instead describing them as people in costumes. For other entries, the English translator adds contextual information to the Chinese entry (for example, for the entry on "pillory," the English writer adds that people were often punished "for 1, 2, or 3 months" and with "various weights"). The dictionary provides a unique glimpse into cross-cultural interactions at the time, in some ways even more than the botanical illustrations. The different hands working on the dictionary, and the value judgements made by the English writer, reveal multiple voices exchanging and evaluating cultural information.[9]

Posthumous legacy

Following Bradby Blake's death in 1773, Whang-y-Tong likely brought the drawings and records that today make up the John Bradby Blake archive to England. Whang-y-Tong arrived in London in 1775 at the latest, and possibly as early as August 1774. As well as passing on the drawings and records to Captain John Blake, Whang-y-Tong met with Joseph Banks, Josiah Wedgwood, and other members of the English elite, and even had his portrait painted by Joshua Reynolds.[1][5]

While the original drawings remained in the hands of the Blake family, being passed down from generation to generation until their 1963 purchase by Paul Mellon,[6] Bradby Blake had already been sending copies of the drawings to Daniel Solander for advice. These copies ended up in the possession of Joseph Banks. Banks subsequently commissioned a manual for British plant collectors working in China, based on the illustrations in Bradby Blake's drawings. As a result the Bradby Blake drawings became the basis for a chain of influence in botanical art: the manual Banks commissioned was used by the botanist William Kerr, who would influence yet another botanical artist, John Reeves, who became known for his Chinese botanical art. The drawings Bradby Blake commissioned and created with Mauk-Sow-U and Whang-y-Tong were the beginning of a long record of Western interest in Chinese plants.[18]

References

- Goodman, Jordan and Peter Crane (2017). "The Life and Work of John Bradby Blake". Curtis's Botanical Magazine. 34 (4): 231–250. doi:10.1111/curt.12200.

- Mozley, Geraldine (1935). The Blakes of Rotherhithe. Privately Printed.

- Crane, Peter and Zack Loehle (2017). "Introduction". Curtis's Botanical Magazine. 34 (4): 215–230. doi:10.1111/curt.12215.

- Ellis, John (1770). Directions for Bringing Over the Seeds and Plants from the East Indies and Other Distant Countries in a State of Vegetation Together with a Catalog of Such Foreign Plants as are Worthy of being Encouraged in Our American Colonies for the Purpose of Medicine, Agriculture and Commerce. To which is Added, the Figure and Botanical Description of a New Sensitive Plant Called Dionaea Muscipula: Or Venus's Fly-trap. London: L. Davis.

- Clarke, David (2017). "Chinese Visitors to 18th Century Britain and Their Contributions to its Cultural and Intellectual Life". Curtis's Botanical Magazine. 34 (4): 498–521. doi:10.1111/curt.12201.

- Goodman, Jordan (2017). "Following the Thread to Oak Spring: The Afterlife of John Bradby Blake's Canton Drawings". Curtis's Botanical Magazine. 34 (4): 276–278. doi:10.1111/curt.12204.

- Hanser, Jessica (2017). "Two Botanists, a Financial Crisis, and Britain's First Embassy to China". Curtis's Botanical Magazine. 34 (4): 314–322. doi:10.1111/curt.12207.

- McConnell, Anita. "Blake, John Bradby". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2580. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- St. André, James (2017). "John Bradby Blake's Multimedia Dictionary: From Wordlist to Worldview". Curtis's Botanical Magazine. 34 (4): 323–358. doi:10.1111/curt.12208.

- Cooper, Thompson (1886). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 05. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 170.

- Batchelor, Robert (2017). "John Bradby Blake, the Chinese Tallow Tree and the Infrastructure of Botanical Experimentation". Curtis's Botanical Magazine. 34 (4): 402–426. doi:10.1111/curt.12211.

- Noltie, Henry (2017). "John Bradby Blake and James Kerr: Hybrid Botanical Art, Canton and Bengal, c. 1770". Curtis's Botanical Magazine. 34 (4): 427–451. doi:10.1111/curt.12212.

- Pickersgill, Barbara (2017). "The British East India Company, John Bradby Blake and Their Interest In Spices, Cotton and Tea". Curtis's Botanical Magazine. 34 (4): 379–401. doi:10.1111/curt.12210.

- Menzies, Nicholas K. (2017). "Representations of the Camellia in China During Its Early Career in the West". Curtis's Botanical Magazine. 34 (4): 452–474. doi:10.1111/curt.12213.

- Easterby-Smith, Sarah (2017). "Botanical Collecting in 18th Century London". Curtis's Botanical Magazine. 34 (4): 279–297. doi:10.1111/curt.12205. hdl:10023/17202.

- Richard, Josepha; Woudstra, Jan (2017). "'Thoroughly Chinese': Revealing the Plants of the hong Merchant's Gardens Through John Bradby Blake's Paintings" (PDF). Curtis's Botanical Magazine. 34 (4): 475–497. doi:10.1111/curt.12214. S2CID 89932649.

- Huang, Hongwen (2017). "The Plants of John Bradby Blake" (PDF). Curtis's Botanical Magazine. 34 (4): 359–378. doi:10.1111/curt.12214. S2CID 89932649.

- Goodman, Jordan; Jarvis, Charles (2017). "The John Bradby Blake Drawings in the Natural History Museum, London: Joseph Banks Puts Them to Work". Curtis's Botanical Magazine. 34 (4): 251–275. doi:10.1111/curt.12203.

Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cooper, Thompson (1886). "Blake, John Bradby". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 05. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 170.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cooper, Thompson (1886). "Blake, John Bradby". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 05. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 170.

External links

- Block mould for a portrait medallion depicting John Bradby Blake – 1779 The Wedgwood Museum