John Bradford Moore

John Bradford Moore (1855–1926)[1] was a trader who established a post at Crystal, New Mexico, at the western end of the Narbona Pass, where he developed the manufacture of Navajo blankets for sale in the United States.

John Bradford Moore | |

|---|---|

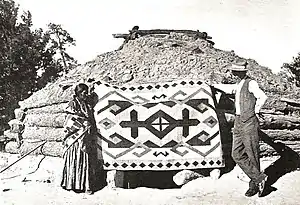

J.B. Moore with a weaver and rug at the Crystal Trading Post, from the 1911 catalog | |

| Born | June 1855 Texas |

| Died | October 14, 1926 (aged 71) [1] |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Trader |

| Known for | Navajo Blankets |

Origins

John Bradford Moore was of Irish origin.[2] He was born in June 1855 in Texas, possibly in Cass County, though on his death certificate of 1926 his age was estimated as "apparently 74".[1] John Bradford Moore of Crook County, Wyoming, marrying Marion A. E. Cooney on 27 Mar 1887.[3] Mary Anne [Marion] Cooney was born on 12 February 1864 in Liverpool, England, and died on 20 September 1917 in LaFeria, Texas.[4] John B. Moore was mayor of Sheridan, Wyoming in 1892.[5] The Moores had one child, Eunice Moore, born in Wyoming on 23 Feb 1894.[4]

Trader

Moore arrived at Narbona Pass in 1896 and bought the trading site, which until then had been open seasonally without permanent buildings. Moore cut timber in the mountains and hauled it down to build a log trading post, which he stocked with supplies carted from the rail head in Gallup. He named his establishment the Crystal Trading Post.[2] Moore wrote of the trading post in 1911, "it is also our mission here to buy any and everything the Navajo has to sell ... to sell him in turn ... everything, in fact, that he has need for."[6]

During the winter months, Moore employed Navajo weavers to make rugs. He ensured that the wool and the weaving were good quality, and created designs of his own,[lower-alpha 1] quickly gaining a reputation as a source of good quality rugs.[2] He would buy local wool, but send it for mechanical cleaning and carding to eastern woolen mills.[7] The mills would also dye some of the wool in blue or black. Moore would issue the dyed wool, along with undyed gray and brown wool, to the most skilled weavers.[6] In a break with tradition, Moore had the sixteen or so weavers who worked for him repeat the same design again and again.[8] In a 1910 article, Moore noted that many excellent weavers were under twenty years old, and often the older women suffered from trachoma or other problems with their eyes that prevented them from producing good quality rugs. He paid low wages. Talking of the weaver's life, he said, "there is no more dismal wage proposition than her remuneration for her part in the industry. Given any other paying outlet for her labor, there would very soon be no such thing as a blanket industry ... it is her one and only way of earning money."[9]

Moore's business flourished, and in 1903 and in 1911 he published mail-order catalogs, drawing business from across the United States.[2] In his 1903 catalog, Moore made much of the authenticity of his products. The catalog included photographs of the interior and exterior of the trading post and the land around it, and of Navajo people, outdoor looms and hogans. He said: "While this booklet makes no claim of being a pioneer in its field, I think it may claim to be the first of its kind published and distributed from the very center of the Navajo Indian Reservation, by an Indian trader living among and dealing directly with the Indans who makes the goods which it illustrates and describes."[10] Moore left the reservation in 1911 due to a scandal.[11] He sold the post to his manager, Jesse A. Molohon.[12] Molohon continued to introduce complex non-Navajo styles that probably drew on Oriental rug designs.[13]

Rug design

Around the turn of the century there was great demand for oriental rugs, so Moore developed simplified oriental patterns for his weavers.[14] Moore understood what the market in the eastern United States would value, and in his catalog stressed the use of natural materials and primitive technology. Despite this, he introduced production-line techniques, and had no problem with using machine-produced yarns with synthetic dyes. When it was too obvious that the materials were commercial, Moore made a point of the authenticity of the spiritual qualities of the works.[15] Moore had considerable influence in the development of Navajo rugs as a form of art. Both the Two Gray Hills and the Crystal styles of rug evolved from Moore's designs.[16]

Until the 1930s the Crystal rugs were bordered, with a central design woven in natural colors, sometimes with some red. After this, the style changed to banded rugs with distinctive "wavy" lines made by alternating weft strands in two or three different colors. A typical new-style Crystal rug will alternate groups of two or three wavy or solid lines with broader bands decorated with patterns representing squash blossoms or geometrical motifs. The newer rugs are woven in muted colors such as rust, rich brown and grey, but may include pastel colors.[17]

Bibliography

- Moore, John Bradford (1901). John Marshall: By J.B. Moore. Ginn. p. 19. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- Moore, John Bradford. Catalogue of Navajo Baskets. The Indian Print Shop. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- Moore, John Bradford (December 1986). The Navajo: a reprint in its entirety of a catalogue published by J.B. Moore, Indian trader, of the Crystal Trading Post, New Mexico, in 1911. Avanyu Publishing. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-936755-01-4. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- Moore, John Bradford (August 1988). The catalogues of fine Navaho blankets, rugs, ceremonial baskets, silverware, jewelry & curios: originally published between 1903 and 1911. Avanyu Pub. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-936755-05-2. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

References

Notes

- A number of Moore's designs incorporated the "whirling log" symbol, a swastika. In the 1940s, this became unpopular with purchasers.[2]

Citations

- Death certificate.

- James 1988, p. 46.

- Details For Marriage ID#297463.

- HI Family Group Sheet.

- Leonard, Suzanne (1998). "Mayors of Sheridan WY". GenWeb Project. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- Powers 2002, p. 69.

- Ortiz & Sturtevant 1983, p. 596.

- M'Closkey 2008, p. 154.

- M'Closkey 2008, p. 147.

- Wilkins 2008, p. 65.

- M'Closkey 2008, p. 146.

- Linford 2005, p. 75.

- Graburn 1976, p. 96.

- Campbell 2006, p. 144.

- Wilkins 2008, p. 65-66.

- Neyland 1992, p. 18.

- Lamb 1992, p. 20.

Sources

- Campbell, Gordon (2006-11-09). The Grove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts: Two-volume Set. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518948-3. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- "Details For Marriage ID#297463". BYU-Idaho and David O. McKay Library. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- Graburn, Nelson H. H. (1976). Ethnic and Tourist Arts: Cultural Expressions from the Fourth World. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03842-4. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- "HI Family Group Sheet for John Bradford MOORE Family". FGS Project. Archived from the original on 2015-09-19. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- James, Harold L. (1988). H.L. James's rugs and posts: the story of Navajo weaving and Indian trading. Schiffer Pub. ISBN 9780887401343. Retrieved 2012-08-24.

- Lamb, Susan (1992). A Guide to Navajo Rugs. Western National Parks Association. ISBN 978-1-877856-26-6. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- Linford, Laurance D. (2005-09-01). Tony Hillerman's Navajoland: Hideouts, Haunts, and Havens in the Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee Mysteries. University of Utah Press. ISBN 978-0-87480-848-3. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- M'Closkey, Kathy (2008-05-30). Swept Under the Rug: A Hidden History of Navajo Weaving. UNM Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-2832-8. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- Neyland, Charlotte Smith (1992-12-01). Southwest Traveler: A Travelers Guide to Southwest Indian Arts and Crafts. American Traveler Press. ISBN 978-1-55838-129-2. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- Ortiz, Alfonso; Sturtevant, William C. (1983-10-20). Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 10: Southwest. Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-16-004579-0. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- Powers, Willow Roberts (2002). Navajo Trading: The End of an Era. UNM Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-2322-4. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- Wilkins, Teresa J. (2008-05-15). Patterns of Exchange: Navajo Weavers and Traders. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3757-5. Retrieved 2012-08-23.