John Cope (British Army officer)

Sir John Cope KB MP (July 1688 – 28 July 1760) was a British soldier, and Whig Member of Parliament, representing three separate constituencies between 1722 and 1741. He is now chiefly remembered for his defeat at Prestonpans, the first significant battle of the Jacobite rising of 1745 and which was commemorated by the tune "Hey, Johnnie Cope, Are Ye Waking Yet?", which still features in modern Scottish folk music and bagpipe recitals.

Sir John Cope | |

|---|---|

Cope, as Colonel, 39th Foot | |

| Governor of Limerick | |

| In office 1751 – 28 July 1760 | |

| Commander-in-Chief, Scotland | |

| In office August 1743 – September 1745 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | July 1688 Camden, London, England |

| Died | 28 July 1760 (aged 72) London, England |

| Resting place | St James's Church, Piccadilly[1] |

| Relations | Sir John Cope, 6th Baronet |

| Education | Westminster School |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Years of service | 1707–1751 |

| Rank | Lieutenant general |

| Unit | 7th Dragoons |

| Battles/wars | |

His military service included the wars of the Spanish and Austrian Successions. Like many of the senior officers present at Dettingen in 1743, victory resulted in promotion, and he was appointed military commander in Scotland shortly before the 1745 Rising. Although exonerated by a court-martial in 1746, Prestonpans ended his career as a field officer.

In 1751, he was appointed governor of the Limerick garrison, and deputy to Viscount Molesworth, commander of the army in Ireland. He died in London on 28 July 1760.

Biographical details

For someone who held high rank, Cope's background is unusually obscure, and for many years biographies referred to his parentage as unknown.[2] His father Henry Cope (1645 – c.1724), was a captain in the Foot Guards, who resigned his commission in April 1688 in order to marry Dorothy Waller. While Cope's date of birth is often given as 1690, parish records show he was baptised on 7 July 1688 at St Giles in Camden; he had two siblings, Mary (1679–1758) and a brother Henry, who died young.[3]

The Cope baronets of Hanwell were the senior branch of the family, with other Copes spread throughout England and Ireland. His grandfather William (1612–1691) fought for Parliament in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, married his brother's widow, and purchased an estate in Icomb, Gloucestershire.[4]

William allegedly disapproved of Henry's marriage, and only allowed him use of Icomb during his lifetime. When he died in 1724, it passed first to his sister Elizabeth (1647–1731), then to his niece Elizabeth (1682–1747), effectively disinheriting John.[5]

Cope's cousin, another Sir John Cope (1673–1749), was disinherited by his father for similar reasons, but also had an extremely successful career. He became a director of the Bank of England in 1706, sat as an MP from 1708 to 1741, and succeeded his father as baronet.[6]

In 1709, Cope had a son James, whose mother is unknown; he later became commercial consul in Hamburg, and was briefly an MP before dying unmarried in 1756, four years before his father.[7] In December 1712, Cope married Jane Duncombe, supposedly an illegitimate sister of Baron Feversham (1695–1763), heir to Sir Charles Duncombe (1648–1711), one of the richest men in Britain.[5]

While Jane's date of death is unrecorded, in August 1736 Cope remarried, his second wife being an Elizabeth Waple, of whom little is known.[5] In July 1758, he wrote to Sir Robert Wilmot (1708–1772), referring to the 'malice and abuse' of his relatives and asking him to act as trustee for John and Elizabeth, his two children by a Mrs. Metcalf. To ensure his direct family would not benefit, if his children died, Cope left his property to Sir Robert's son.[8]

John Metcalf (ca 1746–1771) was educated at Eton, quickly spent the £3,000 left him by his father, ran into debt, and in 1771 committed suicide in Edinburgh.[9] Elizabeth became the second wife of Sir Alexander Leith (1741–1780); she is described only as 'a daughter of Sir John Cope,' and no mention is made of their two sons.[10]

Career

Educated at Westminster School, in 1706 he joined the household of Lord Raby (1672–1739), British ambassador to Prussia. In 1707, Raby arranged for Cope to be commissioned into the Royal Regiment of Dragoons, then fighting in Spain under James Stanhope, part of the War of the Spanish Succession. Appointed aide-de-camp to Stanhope, Cope took part in the 1708 capture of Minorca and the Battle of Almenara in 1710.[11]

When George I succeeded in 1714, the Whigs formed the new government, with Stanhope as its dominant figure. In 1715, Cope was commissioned captain in the 2nd Foot Guards, then the Horse Guards in 1720. Both units were normally based in London, the Horse Guards having served there continuously since 1691, providing security for the monarch and government. This gave officers like Cope regular contact with highly influential people, while being in London made it easier to combine political and military careers.[3]

After Stanhope died in 1721, Sir Robert Walpole replaced him as chief minister and in the 1722 election, Cope was elected MP for the Whig-controlled constituency of Queenborough. While relatives like Edward Cope Hopton (1708–1754) were Tory MPs, Cope, his former brother-in-law Feversham, his cousin Sir John, and nephew Monoux Cope (1696–1763), were all Whigs. In 1727, he was MP for Liskeard; defeated at Orford in 1734, he was returned unopposed in a 1738 bye-election. However, as Walpole's influence weakened, many Whig MPs did not contest the 1741 election, including Cope.[6]

His military career continued to progress. In 1730, he became colonel of the 39th Foot, then successively the 5th Foot, the 9th Dragoons and finally the 7th Dragoons in 1741. He served in Flanders during the War of the Austrian Succession and was promoted lieutenant general in February 1743. He led a cavalry brigade at the Battle of Dettingen in June 1743, where King George II became the last ruling British monarch to command troops in battle. In the aftermath of victory, Cope was appointed commander of military forces in Scotland.[6]

1745 Rising

The July landing of Prince Charles on Eriskay was confirmed in early August. Most of Cope's 3,000–4,000 men were inexperienced recruits, but his main handicap was the poor advice he received from local experts, particularly John Hay, 4th Marquess of Tweeddale, the Secretary of State for Scotland.[12]

Leaving his cavalry at Stirling under Thomas Fowke, Cope and the infantry marched on Corrieyairack Pass, the key connection point between the Western Highlands and the Lowlands. He found the Jacobites already in possession, and after conferring with his officers, withdrew to Inverness on 26 August, leaving Edinburgh exposed. Using the newly constructed military road network, the lightly equipped Jacobite army moved much faster than expected.[13]

Cope loaded his troops onto ships at Aberdeen, and reached Dunbar on 17 September, only to find Charles had entered the city earlier the same day.[14] Joined by Fowke and the cavalry, Cope advanced towards Edinburgh, confident he could deal with a Jacobite army of no more than 2,000.[15] While a reasonable assessment, his army's effectiveness was undermined by inexperience, and the poor quality of many senior officers. This included James Gardiner, later mythologised for his heroic death, who was described as a 'nervous wreck'. On 16 September, his dragoons fled in panic from a small party of Highlanders, the so-called 'Coltbridge Canter'.[16]

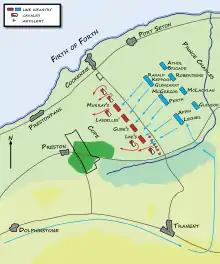

The two armies made contact on the afternoon of 20 September; Cope's forces faced south, with a marshy area immediately in front, and park walls protecting their right (see Map). The 1746 court-martial agreed the ground was well chosen, and the disposition of his troops appropriate.[17] During the night the Jacobites moved onto his left flank and Cope wheeled his army to face east (see Map); his dragoons panicked and fled, exposing the infantry in the centre. Attacked on three sides, they were over-run in less than 15 minutes, with their retreat blocked by the park walls to their rear; government losses were 300 to 500 killed or wounded and 500 to 600 taken prisoner.[18]

Unable to rally his troops, Cope left the field with his artillery commander, Colonel Whitefoord, while his infantry commander Peregrine Lascelles fought his way out. Joined by Fowke and the dragoons, they reached Berwick-upon-Tweed the next day with some 450 survivors.[19] Several hours after the battle, Cope wrote to Tweeddale; I cannot reproach myself; the manner in which the enemy came on was quicker than can be described...and the cause of our men taking on a destructive panic...[20]

He was replaced as commander in Scotland first by Roger Handasyd, then Henry Hawley, who was also over-run by the Highland charge at Falkirk Muir in January 1746. Cope had retained his ability to make friends in high places; by inviting him to a public reception, George II indicated his personal support. Tried by a court-martial in 1746, the only witness against Cope was the mathematician Richard Jack, whose testimony was discounted owing to his exaggeration of his own accomplishments and the lack of corroboration. In the end, all three officers were exonerated,[21] the Court ruling that the defeat had occurred due to the 'shameful conduct of the private soldiers'.[22]

Despite this, Cope never held field command again, although Lascelles and Fowke continued their careers.[23] A modern historian has summarised the Report's findings as follows:

The Report of the Board's proceedings was published in 1749. Anyone who scrutinizes it closely can only conclude that the Board was correct. What emerges from the pages is not, perhaps, the portrait of a military genius but one of an able, energetic and conscientious officer who weighed his options carefully and who anticipated - with almost obsessive attention to detail - every eventuality except the one which he could not have provided for in any case: that his men would panic and flee.[24]

Legacy

In 1751, Cope was appointed Governor of Limerick, and deputy to Viscount Molesworth, commander of the army in Ireland; neither post required residence, and he seems to have quietly accepted the end of his career. Writing to Fowke on 19 July 1753, he states 'I am just as desirous not to be employed, as those who could employ me are unwilling to do it, so in that we are perfectly agreed.' He also suffered from severe gout, a common illness at the time; another letter dated 8 July 1755 mentions his residence in Bath, whose Spa waters were a favourite remedy for invalids.[25]

Many perceptions of Cope's responsibility for Prestonpans come from third party accounts, none of whom were present, and often written with specific objectives. In his 1747 book Life of Colonel Gardiner, Nonconformist minister Philip Doddridge turned evangelical convert Gardiner into a Christian hero, largely by ridiculing Cope; this remains an enduring myth.[26]

Gardiner also features in Walter Scott's 1817 novel Waverley, his heroic death convincing the English Jacobite hero the future lies with the Union, not the Stuarts.[27] The suggestion attributed to Lord Mark Kerr, governor of Berwick, that Cope fled so fast, he brought news of his own defeat, appears to be yet another embellishment by Scott.[28]

The most enduring legacy was provided by Alan Skirving, a local farmer who visited the battlefield later that afternoon where he was, by his own account, mugged by the victors. He wrote two songs, "Tranent Muir" and the better known "Hey, Johnnie Cope, Are Ye Waking Yet?", a tune that still features in Scottish folk music and bagpipe recitals.[29]

References

Citations

- The Register Book for Burials. In the Parish of St James in Westminster in the County of Middlesex. 1754-1812. 5 August 1760.

- Cope 1935, p. 170.

- Cope 1935, p. 171.

- A History of the County of Worcester: Volume 3 1913, pp. 410–412.

- Brumwell 2004.

- Newman 1970.

- Cannon 1964.

- "Sir John Cope to Sir R Wilmot, 27 Jul 1758 A new will". Derbyshire Records Office. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- Bullock 1952, p. 179.

- Namier 1964.

- Burton & Newman 1963, p. 659.

- Royle 2016, pp. 17–18.

- Royle 2016, p. 20.

- Duffy 2003, p. 198.

- Tomasson & Buist 1978, p. 42.

- Corsar 1941, pp. 93–94.

- "The London Gazette" (PDF). No. 8585. 4 November 1746. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- Charles 1817, pp. 51–52.

- Duffy, Christopher. "Victory at Prestopans and its significance for the 174 campaign". p. 14. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- Elcho 1907, p. 303.

- Robins 1749.

- Blaikie 1916, p. 434.

- Dalton 1904, p. 269.

- Margulies 2002.

- "Two autograph letters from Sir John Cope to Lt.-General Thomas Fowke; 19 July 1753 & 8 July 1755". Lyons & Turnbull. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- Cook, Faith (December 2015). "The surprising story of Colonel James Gardiner (1688–1745)". The Evangelical Times. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- Sroka 1980, pp. 139–162.

- Cadell 1898, p. 269.

- "Johnny Cope - Highland Bagpipes traditional tunes' stories by Stephane BEGUINOT".

Sources

- A History of the County of Worcester: Volume 3. Victoria County History. 1913.

- Blaikie, Walter Biggar (1916). Publications of the Scottish History Society (Volume Ser. 2, Vol. 2 (March, 1916) 1737-1746). Scottish History Society.

- Brumwell, Stephen (2004). "Cope, Sir John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6254. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Bullock, H (1952). "1058. The Mystery of Sir John Cope". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 30 (24).

- Burton, I.F.; Newman, A.N. (1963). "Sir John Cope: Promotion in the Eighteenth-Century Army". The English Historical Review. 78 (309).

- Cadell, Sir Robert (1898). Sir John Cope and the Rebellion of 1745. William Blackwood & Sons.

- Cannon, JA (1964). Namier, Lewis; Brooke, John (eds.). COPE, James (c.1709-56) in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1754-1790. HMSO.

- Charles, George (1817). History of the transactions in Scotland, in the years 1715-16 & 1745-1746; Volume II. Gilchrist & Heriot.

- Cook, Faith (December 2015). "The surprising story of Colonel James Gardiner (1688–1745)". The Evangelical Times. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- Cope, EE (1935). "The Mystery of Sir John Cope". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 14 (55).

- Corsar, Kenneth Charles (1941). "The Canter of Coltbridge; 16th September 1745". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 20 (78).

- Dalton, Charles (1904). English army lists and commission registers, 1661-1714 Volume V. Eyre and Spottiswood.

- Duffy, Christopher (2003). The '45: Bonnie Prince Charlie and the untold story of the Jacobite Rising. Orion. ISBN 978-0-304-35525-9.

- Elcho, Lord David (1907). Charteris, Edward Evan (ed.). A short account of the affairs of Scotland : in the years 1744, 1745, 1746. David Douglas, Edinburgh.

- Margulies, Martin B (2002). "Unlucky or incompetent? History's verdict on General Sir John Cope". History of Scotland. 2 (3).

- Namier, Lewis (1964). Namier, Lewis; Brooke, John (eds.). LEITH, Alexander (1741-80), of Burgh St. Peter, Norfolk in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1754-1790. HMSO.

- Newman, AM (1970). Sedgwick, Romney (ed.). COPE, John (1690–1760) in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1715-1754. HMSO.

- Robins, Benjamin (1749), A Report of the Proceedings and Opinions of the Board of General Officers, on Their Examination into the Conduct, Behaviour, and Proceedings of Lieutenant-General Sir John Cope, Knight of the Bath, Colonel Peregrine Lascelles, and Brigadier-General Thomas Fowke from the Time of the Breaking Out of the Rebellion in North-Britain in the Year 1845, till the Action at Preston-Pans Inclusive..., Dublin: George Faulkner.

- Royle, Trevor (2016). Culloden; Scotland's Last Battle and the Forging of the British Empire. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1-4087-0401-1.

- Sedgwick, Romney, ed. (1970). COPE, Sir John (1673–1749), of Bramshill, Hants; in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1715-1754. HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-880098-3.

- Sroka, Kenneth M. (January 1980). "Education in Walter Scott's Waverley". Studies in Scottish Literature. 15 (1). eISSN 0039-3770.

- Tomasson, Katherine; Buist, Francis (1978). Battles of the Forty-five. HarperCollins Distribution Services. ISBN 978-0-7134-0769-3.