John H. Sterrett

John H. Sterrett (1815–June 18, 1879) was a ship captain and investor.

John H. Sterrett | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1815 Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | June 18, 1879, age 64 Galveston, Texas, U.S. |

| Occupation | Steamboat captain |

| Employer(s) | Self-employed, Houston and Galveston Navigation Company, Houston Navigation Company |

| Title | Superintendent |

| Spouse | Susan Wilson |

| Children | Henrietta, Josephine, Julia, Ida, William, Warner, E. Howard, and Adelle |

| History of Texas | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Career

John H. Sterrett was born around 1815 in Pennsylvania. He was already operating steamboats as early as 1838 in Ohio and Pennsylvania. He redeployed his small steamer, Rufus Putnam, to New Orleans later in 1838, and then to the Republic of Texas in January 1839. He offered packet service on Buffalo Bayou and Galveston Bay, which included the towns of Houston and Galveston, Texas.[1]

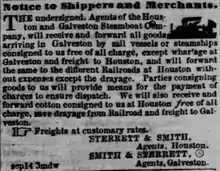

Sterrett also invested and managed transportation companies. In 1851, he invested in the Houston and Galveston Navigation Company, a company headed by William Marsh Rice. Sterrett also managed the company's fleet.[2][3]

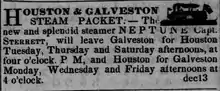

Buffalo Bayou and Galveston Bay were venues for many impromptu steamboat races. Sterrett participated in some of these, and one of these ended in catastrophe. On March 22, 1853, he was racing Captain Webb of Farmer, a vessel which Sterrett himself had recently mastered. The boiler of Farmer exploded, killing about half of the ship's seventy-two persons on board. Local newspapers gave Sterrett mixed revues: they acknowledged his heroism in turning Neptune around to rescue some of Farmer's passengers and crew, but charged him with recklessness for participating in the deadly race. The incident may have had a sobering effect on Sterrett, who was later known for the safety of his shipping operations.[4][5]

In 1854, Rice and other investors of the Houston and Galveston Navigation Company formed a new company. Sterrett would again serve as a managing partner in the Houston Navigation Company, which started with a strategy of competing for United States Mail contracts. Galveston was a transportation hub, controlling traffic for 150,000 pieces of mail from the eastern United States to Texas and California.[6]

Sterrett was the superintendent of the Houston Navigation Company's fleet, and he assumed a similar role for the Texas Marine Department during the Civil War.[7] His responsibility included the Brazos, Sabine, and Trinity rivers, as well as the Galveston Bay system, where the Texas Marine Department operated as many as thirteen steamships.[8] Months after the war, he acquired two Union tinclads, Silver Cloud and St. Clair, and converted them for civilian service between Houston and Galveston.[9] Houston Navigation Company did not survive the war, so he ran his own packet service in 1865 and 1866. In October 1866, William Marsh Rice, the City of Houston, and many investors from the previous firm organized the Houston Direct Navigation Company. They tapped Sterrett as the new company's fleet superintendent and appointed him as one of the officers. In addition, he coordinated lightering, or the transfer of freight from one ship to another without the benefit of a wharf. This enabled the company to obviate the high wharfage fees at the port of Galveston. He also purchased two tugboats for pulling barges laden with cotton as an efficient means of conveying freight.[10]

Sterrett retired from Houston Direct Navigation Company in 1875.[11] He piloted steamers between Galveston and Houston 4,000 times throughout his career.[12]

Death

Sterrett died on June 18, 1879, in Galveston, Texas.[11]

Ship list

Ships owned or mastered by Sterrett (in chronological order by year built):

| Name | Year built | Built at | Acquired | Power | Propulsion | Tonnage | Length | Beam | Draft | Out of service | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rufus Putnam[15] | 1835 | Marrietta, Ohio | 1838 | Steam | Sidewheeler | 98 | 127 | Ohio River (1838). New Orleans (1838). Buffalo Bayou (1839). | |||

| Dayton[15] | 1835 | Pittsburgh, PA | Steam | Sidewheeler | 111 | 1845 | Exploded. Sterrett mastered from 1844.[16] | ||||

| Farmer[15] | 1849 | Brownsville, PA | Steam | Sidewheeler | 158 | 1853 | Master until 1850. Exploded during race.[17] | ||||

| Neptune[15] | 1852 | Brownsville, PA | Steam | Sternwheeler | 214 | 1858 | Off the lists | ||||

| Silver Cloud[15] | 1862 | Brownsville, PA | 1865 | Steam | Sternwheeler | 236 | 155 | 33.5 | 5.3 | 1866 | Three boilers. Lost to snag. Union Navy Tinclad 28. |

| St. Clair[15] | 1862 | Belle Vernon, PA | 1865 | Steam | Sternwheeler | 203 | 156 | 32.6 | 4.9 | After 1869 | Two boilers. Off the lists, 1869. Union Navy Tinclad 19. |

| J.H. Whitelaw[15] | 1865 | Beardstown, Illinois | Steam | Sidewheeler | 439 | 1871 | Buffalo Bayou | ||||

| Superior[15] | 1866 | Buffalo, NY | Steam | Propeller | 14 | 1877 | Tugboat. Abandoned. | ||||

| Ontario[15] | 1866 | Buffalo, NY | Steam | Propeller | 8 | 1929 | Tugboat. Abandoned. | ||||

| T.M. Bagby[15] | 1868 | Louisville, Kentucky | Steam | Sidewheeler | 508 | 175 | 50 | 1876 | Buffalo Bayou. Dismantled. | ||

| Diana[15] | 1870 | Cincinnati, Ohio | 1870 | Steam | Sidewheeler | 450 | 171 | 32 | Converted to barge | ||

| Charles Fowler[15] | 1871 | Steam | Houston Direct Navigation Company | ||||||||

| Lizzie[15] | 1871 | Jeffersonville, IN | Steam | Sidewheeler | Perhaps 1880 | ||||||

| [15] | |||||||||||

References

- Hall, Andrew W. (2012). The Galveston–Houston Packet: Steamboats on Buffalo Bayou. Charleston, SC: History Press. pp. 39–41. ISBN 978-1-60949-591-6.

- Sibley, Marilyn McAdams (1968). Houston: A History. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 69–70.

- Hall (2012), p. 49.

- Hall (2012), pp. 51–52.

- Sibley (1968), p. 71.

- Hall (2012), pp. 56–57.

- Hall (2012), p. 67.

- Hall (2012), 80–81.

- Hall (2012), pp. 83–84.

- Hall (2012), pp. 86–89.

- Hall (2012), p. 102.

- Sibley (1968), pp. 70–71.

- Hall (2012), p. 61.

- Hall (2012), p. 101.

- Hall (2012), pp. 116–122.

- Hall (2012), p. 47

- Hall (2012), p. 51.