John Surratt

John Harrison Surratt Jr. (April 13, 1844 – April 21, 1916) was an American Confederate spy who was accused of plotting with John Wilkes Booth to kidnap U.S. President Abraham Lincoln; he was also suspected of involvement in the Abraham Lincoln assassination. His mother, Mary Surratt, was convicted of conspiracy by a military tribunal and hanged; she owned the boarding house that the conspirators used as a safe house and to plot the scheme.

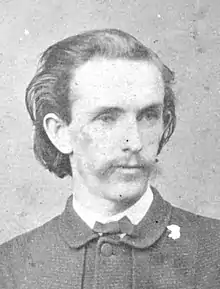

John Surratt | |

|---|---|

Surratt in 1868 | |

| Born | John Harrison Surratt Jr. April 13, 1844 Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Died | April 21, 1916 (aged 72) |

| Burial place | New Cathedral Cemetery |

| Nationality | American[1] |

| Alma mater | |

| Occupation(s) | U.S. postmaster, farmer, parochial school teacher, Pontifical Zouave, public lecturer, company treasurer |

| Known for | Co-conspirator in plan to kidnap U.S. President Abraham Lincoln, Friend of John Wilkes Booth |

| Spouse |

Mary Victorine Hunter

(m. 1872) |

| Children | 7 |

| Parent(s) | Mary Surratt John Harrison Surratt |

| Espionage activity | |

| Allegiance | Confederate States of America |

| Service branch | Confederate Secret Service |

| Rank | courier, spy |

He eluded arrest following the assassination by fleeing to Canada and then to Europe. He thus avoided the fate of the other conspirators, who were hanged. He served briefly as a Pontifical Zouave but was recognized and arrested. He escaped to Egypt but was eventually arrested and extradited. By the time of his trial, the statute of limitations had expired on most of the potential charges which meant that he was never tried.

Early life

He was born in 1844, to John Harrison Surratt Sr. and Mary Elizabeth Jenkins Surratt, in what is today Congress Heights. His baptism took place in 1844 at St. Peter's Church, Washington, D.C. In 1861, he was enrolled at St. Charles College, where he was studying for the priesthood[2] and also met Louis Weichmann. When his father suddenly died in 1862, Surratt was appointed the postmaster for Surrattsville, Maryland.

Plot to kidnap Lincoln

Surratt served as a Confederate Secret Service courier and spy. After he had been carrying dispatches about Union troop movements across the Potomac River. Dr. Samuel Mudd introduced Surratt to Booth on December 23, 1864, and Surratt agreed to help Booth kidnap Lincoln. The meeting took place at the National Hotel, in Washington, D.C., where Booth lived.

Booth's plan was to seize Lincoln and take him to Richmond, Virginia, to exchange him for thousands of Confederate prisoners of war. On March 17, 1865, Surratt and Booth, along with their comrades, waited in ambush for Lincoln's carriage to leave the Campbell General Hospital to return to Washington. However, Lincoln had changed his mind and remained in Washington.

William H. Crook, one of Lincoln's bodyguards, claimed that Surratt had boarded the River Queen shortly before the Third Battle of Petersburg, using the name of Smith and demanding to see Lincoln (who was aboard at the time). Crook later stated his belief that Surratt "was seeking an opportunity to assassinate the President at this time".[3]

Assassination of Lincoln

After the assassination of Lincoln, on April 14, 1865, Surratt denied any involvement and said that he was then in Elmira, New York. He was one of the first people suspected of the attempt to assassinate Secretary of State William H. Seward, but the culprit was soon discovered to be Lewis Powell.

In hiding

When he learned of the assassination, Surratt fled to Montreal, Canada East, arriving on April 17, 1865. He then went to St. Liboire, where a Catholic priest, Father Charles Boucher, gave him sanctuary. Surratt remained there while his mother was arrested, tried, and hanged in the United States for conspiracy.

Aided by ex-Confederate agents Beverly Tucker and Edwin Lee, Surratt, disguised, booked passage under a false name. He landed at Liverpool in September, where he lodged in the oratory at the Church of the Holy Cross.[4]

Surratt would later serve for a time in the Ninth Company of the Pontifical Zouaves, in the Papal States, under the name John Watson.[5][6]

An old friend, Henri Beaumont de Sainte-Marie, recognized Surratt and notified papal officials and the US minister in Rome, Rufus King.[7]

On November 7, 1866, Surratt was arrested and sent to the Velletri prison. He escaped and lived with the supporters of Garibaldi, who gave him safe passage. Surratt traveled to the Kingdom of Italy and posed as a Canadian citizen named Walters. He booked passage to Alexandria, Egypt, but was arrested there by US officials on November 23, 1866, still in his Pontifical Zouaves uniform.[8] He returned to the US on the USS Swatara to the Washington Navy Yard in early 1867.[9]

Trial

Eighteen months after his mother was hanged, Surratt was tried in a Maryland civilian court. It was not before a military commission, unlike the trials of his mother and the others, as a US Supreme Court decision, Ex parte Milligan, had declared the trial of civilians before military tribunals to be unconstitutional if civilian courts were still open.

Judge David Carter presided over Surratt's trial, and Edwards Pierrepont conducted the federal government's case against him. Surratt's lead attorney, Joseph Habersham Bradley, admitted Surratt's part in plotting to kidnap Lincoln but denied any involvement in the murder plot. After two months of testimony, Surratt was released after a mistrial; eight jurors had voted not guilty, four voted guilty.

The statute of limitations on charges other than murder had run out, and Surratt was released on bail.[10]

Later life

Surratt tried to farm tobacco and then taught at the Rockville Female Academy. In 1870, as one of the last surviving members of the conspiracy, Surratt began a much-heralded public lecture tour. On December 6, at a small courthouse in Rockville, Maryland, in a 75-minute speech, Surratt admitted his involvement in the scheme to kidnap Lincoln. However, he maintained that he knew nothing of the assassination plot and reiterated that he was then in Elmira. He disavowed any participation by the Confederate government, reviled Weichmann as a "perjurer" who was responsible for his mother's death and said his friends had kept from him the seriousness of her plight in Washington. After that revelation, it was reported in Washington's Evening Star that the band played "Dixie" and a small concert was improvised, with Surratt the center of female attention.

Three weeks later, Surratt was to give a second lecture in Washington, but it was canceled because of public outrage.[11]

Surratt later took a job as a teacher in St. Joseph Catholic School in Emmitsburg, Maryland. In 1872, Surratt married Mary Victorine Hunter, a second cousin of Francis Scott Key. The couple lived in Baltimore and had seven children.[12]

Some time after 1872, he was hired by the Baltimore Steam Packet Company. He rose to freight auditor and, ultimately, treasurer of the company. Surratt retired from the steamship line in 1914 and died of pneumonia in 1916, at the age of 72.[13]

He was buried in the New Cathedral Cemetery, in Baltimore.[14]

In film

Surratt was portrayed by Johnny Simmons in the 2010 Robert Redford film The Conspirator.[15]

See also

- James W. Pumphrey – Surratt introduced Booth to Pumphrey, who supplied Booth's getaway horse.

References

- "The Surratt Family Tree – Surratt House Museum". Surrattmuseum.org. Archived from the original on October 28, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- Trindal, Elizabeth Steger (1996), Mary Surratt: An American Tragedy, Pelican Pub. Co., p. 46, ISBN 978-1-56554-185-6, LCCN 95050031

- Crook, William Henry; Gerry, Margarita Spalding (1910). Through five administrations; reminiscences of Colonel William H. Crook, body-guard to President Lincoln. New York, London: Harper & Brothers. pp. 45–47. OCLC 1085597035.

- Steers, Edward (October 21, 2005), Blood on the Moon: The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, University Press of Kentucky, pp. 231–, ISBN 0-8131-9151-3

- Shuey v. United States, 92 U.S. 73 (1875).

- Howard R. Marraro. "Canadian and American Zouaves in the Papal Army, 1868–1870". Canadian Catholic Historical Association Report, 12 (1944–45). pp. 83–102. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

Footnote 1 lists documents and works related to Surratt.

- Martinkus, Mary Salesia (1953). Diplomatic Relations between the United States and the Vatican During the Civil War (MA thesis). Loyola University Chicago. pp. 40–42. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- Hatch, 2016, p. 130

- Hatch, 2016, p. 134

- Loux, Arthur F. (August 20, 2014), John Wilkes Booth: Day by Day, McFarland, p. 224, ISBN 978-0-7864-9527-6

- "The Text of John Surratt's Lecture at Rockville, Maryland". Washington Evening Star. December 7, 1870. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- Trindal, Elizabeth Steger (1996), Mary Surratt: An American Tragedy, Pelican Pub. Co., p. 233, ISBN 978-1-56554-185-6, LCCN 95050031

- "John H. Surratt Dead! Last Of The Alleged Conspirators In The Lincoln Assassination". The New York Times. 1916-04-22. p. 11. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- Jampoler, Andrew C. A., The Last Lincoln Conspirator: John Surratt's Flight from the Gallows, Naval Institute Press, 2009

- Puente, Maria (April 14, 2011). "Redford's 'Conspirator' lets Mary Surratt testify". USA Today. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

Sources

- Hatch, Frederick (June 20, 2016), John Surratt: Rebel, Lincoln Conspirator, Fugitive, McFarland, ISBN 978-1-4766-6513-9

- Jampoler, Andrew C. A. (2008). The Last Lincoln Conspirator. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-407-6.

- Leonard, Elizabeth D. (2005). Lincoln's Avengers; Justice, Revenge, and Reunion after the Civil War. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-32677-2.

- Serup, Paul (2008). Who Killed Abraham Lincoln?. Salmova Press. ISBN 978-0-9811685-0-0.

- Swanson, James L. (2006). Manhunt: The Twelve Day Chase for Lincoln's Killer. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 0-06-051849-9.

- Winkler, H. Donald (2003). Lincoln and Booth; More Light on the Conspiracy. Nashville: Cumberland House. ISBN 1-58182-342-8.

External links

- John Surratt

- Text of John Surratt's public lecture giving his version of the conspiracy

- A map and timeline of John Surratt's two-year flight and eventual capture

- John H. Surratt's career as a teacher after the assassination aftermath