John O'Meally

John O'Meally (June 1840 – 19 November 1863), known informally as 'Jack' O'Meally, was an Australia bushranger. He was recruited to join the Gardiner–Hall gang to carry out the gold escort robbery near Eugowra in June 1862, Australia's largest gold theft.[1] O'Meally became a member of the group of bushrangers led by Johnny Gilbert and Ben Hall, which committed many robberies in the central west of New South Wales. Considered to be the most violent and hot-headed of the group,[2] O'Meally was probably responsible for two murders during this time. The gang managed to evade the police for long periods and became the most notorious of the bushranging gangs of the 1860s. Jack O'Meally was shot and killed during an attack on the 'Goimbla' station homestead in November 1863.

John ('Jack') O'Meally | |

|---|---|

An artist's impression of the bushranger, John O’Meally (detail from the 'Gardiner's Gang' mural in Chesher-street, Eugowra, NSW). | |

| Born | John O'Meally June 1840 Cunningham Creek, near Murrumburrah, New South Wales, Australia |

| Died | 19 November 1863 (aged 23) 'Goimbla' station, near Eugowra, New South Wales |

| Resting place | Gooloogong, New South Wales |

Biography

Family circumstances

John O'Meally was born in June 1840 in the vicinity of Cunningham Creek, south-east of Murrumburrah, the eldest of ten children of Patrick O'Meally and Judith (née Downey).[3][4]

John's father had arrived in Sydney as a transported convict in February 1832 aboard the Norfolk, sentenced with his younger brother to seven years for sheep stealing. The brothers were recorded with the surname 'Malley' and were from country Mayo in Ireland. Patrick O'Meally was granted his Ticket of Freedom in February 1839; in July the same year he married Julia Downey at Galong (east of Murrumburrah).[3]

By 1847 Patrick O'Meally had taken up 'Arramagong' station, with an estimated area of 26,800 acres located at the southern foot of the Weddin Mountains in the Lachlan Squatting District. In that year he was granted a license to depasture stock on the leasehold, with an estimated grazing capability of 800 cattle.[5][6] Patrick O'Meally established and worked the 'Arramagong' run in an informal partnership with his brother-in-law, John Daley (husband of Ellen Downey), though the pastoral run was held in O'Meally's name. The two households lived separately on the station, about a mile and a half distant from each other.[3]

The children of both families probably received at least a rudimentary education; in September 1853 it was recorded that a schoolmaster named John Smith was living on the property.[7] Young Jack O'Meally worked as a stockman on the 'Arramagong' run. He was described as "tall, smart, and a splendid horseman".[8]

In June 1860 Patrick O'Meally was granted a publicans’ license for the Weddin Mount Inn, built beside Emu Creek on the 'Arramagong' run.[9][10] With the gold-rush that occurred in the second half of 1860 at Lambing Flat and, nine months later, the opening up of the Lachlan goldfield at Forbes, the prospects for O'Meally’s inn considerably improved, being situated on a road between the two localities, 25 miles from Lambing Flat and 45 miles from Forbes.[11][12]

By 1861 a disagreement had arisen between the brother-in-laws, Patrick O’Meally and John Daley, over the leasehold of ‘Arramagong’ station. In June 1861 O’Meally placed the property, including stock and buildings, up for auction and Daley discovered the lease was held in O'Meally’s name only.[3] In July 1861 the leasehold of the 'Arramagong' run was sold for £1,370 to Patrick Throsby, a landholder near Berrima.[13]

Gardiner's influence

As the Central West region became more populated Jack O’Meally met Frank Gardiner (at that time was using the alias 'Jones'). Gardiner was a convicted horse- and cattle-thief who had been released on a ticket-of-leave to the Carcoar district, but had left that district to run a butcher shop at Lambing Flat with his friend and associate, William Fogg.[14][15] Gardiner and Fogg were obtaining meat for their business from stolen livestock and developed a network of associates in the district willing to provide animals by dishonest means.[16] Gardiner became a frequent visitor to O’Meally’s inn.[8] It was through Gardiner's network that Jack O’Meally met Johnny Gilbert, who had been working as a horse-breaker at Marengo and supplying cattle to Gardiner.[16]

Frank Gardiner’s butchering business was disrupted when he was arrested in May 1861 on a cattle-stealing charge and committed for trial, but allowed bail. He then absconded, after which his identity as a ticket-of-leave holder absent from his district was discovered. Gardiner hid out at William Fogg’s house near Bigga in the upper Lachlan River district. After being located by two policemen at Fogg’s house in July 1861, Gardiner escaped from captivity after a violent encounter, leaving him injured from the incident.[15] After this incident Gardiner either kept a low profile or left the district for a time, but by February 1862 he began to carry out a series of robberies in the Lambing Flat district, in company with young men from the district attracted to the romance and excitement of the bushranging life. Gardiner used the Weddin Mountains and the nearby Pinnacle Range as refuges and the nearby O’Meally’s inn as a base.[16]

Mid-morning on 10 March 1862 two Lambing Flat storekeepers were robbed of gold and cash by Gardiner and his gang near Big Wombat (ten miles south of Lambing Flat). One of the storekeepers, Alfred Horsington, was suffering from a broken leg and was proceeding towards Lambing Flat in a spring-cart, accompanied by his wife and a boy who was driving the cart. The other storekeeper, Henry Hewitt, was travelling with them on horseback.[17] The group was stopped and ordered to bail-up by Gardiner and three others, O’Meally, John McGuiness and either John Gilbert, John Davis or Samuel Dinnir.[16][18] None of the bushrangers were disguised. The cart and Hewitt’s horse were led off the road into the bush, where a search revealed 253 ounces of gold and £145 cash (being carried by Horsington) and 189 ounces of gold and £172 (taken from Hewitt).[19]

By April 1862 it was reported that "Gardiner has become a perfect 'bogie'" in the goldfield districts of the central west, "and his success has drawn others into his course". It was claimed that the notorious bushranger "is supplied with information by numberless accomplices both in the township and along the roads".[20]

In the vernacular of the bush Jack O’Meally was considered to be 'flash', in common with Gardiner and others such as Gilbert.[21] ‘Flashness’ encompassed a flamboyant style of dress, as well as a predilection for superior horses and saddlery and swaggering manner and attitude.[22]

The Eugowra gold escort robbery

In about May 1862 Gardiner began to plan an ambush on the regular gold escort that transported gold and bank-notes from the Lachlan diggings to Sydney. To achieve this undertaking he recruited seven accomplices: Jack O’Meally, Johnny Gilbert, Ben Hall, Dan Charters, John Bow, Alex Fordyce and Henry Manns. The ambush was planned over a number of weeks, with the gang meeting on ‘Sandy Creek’ station (in the Wheogo district, north-west of the Weddin mountains) in either Hall’s house or the nearby house of Hall’s brother-in-law, John Maguire.[16][23]

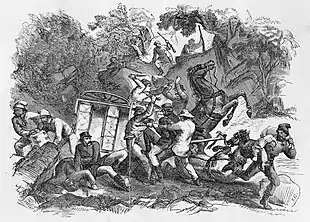

On Sunday, 15 June 1862, the gang of bushrangers commanded by Gardiner ambushed the gold escort near Eugowra, 23 miles east of Forbes, and robbed the coach of gold and bank-notes of an estimated value of £14,000. The regular gold escort from the Lachlan diggings had departed from Forbes late in the morning on its journey to Sydney. The coach was carrying four policemen of the Western Escort, given the task of providing safe passage for a considerable amount of money and gold. At about five o’clock in the afternoon, just under three miles north-east of Eugowra, the coach came across two drays and their teams which were blocking the road, forcing the coach-driver, John Fagan, to slow the horses to a walk in order to pass close to a large rock beside the road. As it passed, the coach was fired upon by the group of eight men concealed behind the large rock and others in the vicinity. The bushrangers were dressed in "red serge shirts, and red nightcaps, with faces blackened". They fired at the driver and policemen in successive volleys, displaying considerable discipline and precision in their actions; as soon as the first group delivered their fire, they fell back to be replaced with the second group. When the gunfire began Fagan jumped off the coach still holding the reins. Several of the escort were wounded in the volleys of gunfire: Sergeant Condell in the box with the driver was hit in his side and Senior-sergeant Moran received a bullet in the groin. The policemen returned fire, but in the exchange of gunfire one or more of the coach horses were struck, causing them to bolt and the vehicle to capsize as the wheels struck broken rocks. When the coach overturned, the bushrangers "began to cheer and rushed down pell mell to secure their booty". The driver and men of the escort scattered into the surrounding bush; "the law of self-preservation came into operation, for every man sought cover from the fire". The outlaws loaded two of the coach horses with the strongboxes and mail-bags and departed. The total plunder stolen from the coach was 2,719 ounces of gold and £3,700 in cash. Sergeant Condell later reported that, as the bushrangers were firing at the coach, they were commanded by one man, "who gave them orders to fire and load" in a voice the policeman recognised as that of Frank Gardiner.[24][25][26]

The colonial government promptly offered a reward for information regarding "the band of armed men, said to be ten in number" who robbed "the Gold Escort from the Lachlan". A notification dated 17 June 1862 announced that a reward of £100 would be paid for information leading to the apprehension and conviction of “each of the guilty parties” (to £1,000 in total). For any accomplice to the robbery who would give such information, a pardon was offered.[27]

The hunt for the gold escort robbers

A party of troopers under Senior-sergeant Sanderson began a search for the gold escort robbers the next day. On Thursday, June 19, Sanderson stopped at Ben Hall’s house near Wheogo Hill, about 20 miles north-west of Grenfell. With nobody at home, Sanderson was leaving when he saw a rider coming from the hill, heading towards Hall’s or nearby Maguire’s house. As the rider drew closer the man could see they were police and immediately turned and rode away at full gallop. They followed his tracks to Wheogo Hill where they found the tracks of four others who had recently decamped. With the assistance of the Aboriginal tracker, Hastings, the troopers followed the bushranger’s tracks for about twenty-five miles. Finding themselves "so hotly pursued" the outlaws let their pack-horse go, enabling them to escape. The policemen found strapped to the pack-horse about 1,500 ounces of gold, a police cloak and two breech-loading carbines, all of which had been stolen from the gold escort coach.[28][24] Sanderson’s party followed one set of tracks for about nine miles from where the packhorse was found, which led them past John Nowlan’s station to the vicinity of Jack O’Meally’s place near the Weddin Ranges. On nightfall the troopers met Alex Fordyce on horseback who said he had come from O’Meally’s and was on his way to Nowlan’s.[28]

In the meantime Frederick Pottinger and a party of police and volunteers were following the tracks of five riders and two pack horses who had followed the stock-route to the Murrumbidgee River near Narrandera, and were following the river downstream. It was believed Gardiner was one of the men being pursued.[29] Pottinger followed the trail to Hay, on the lower Murrumbidgee, before turning back, convinced that Gardiner and his companions had turned south and crossed into Victoria. By this time only two riders remained in Pottinger’s party, Sergeant Lyons and Richard B. Mitchell, the Clerk of Petty Sessions at Forbes. On July 7 near 'Mirrool' station, north-east of Narrandera, they met three young men on the road, leading a pack-horse. When Pottinger began asking questions of the men, one of them suddenly dug his spurs into his horse's flanks and galloped away into the surrounding bush. At this Pottinger and Mitchell drew their pistols and ordered the remaining two men "to stand". A search of the pack-horse revealed 242 ounces of gold in a flour bag and one of the men had £135 in bank-notes in his possession. The next morning Pottinger and his men continued on the road to Forbes with their two captives.[30]

Unbeknownst to Pottinger at that stage, his captives' names were Charles Gilbert and Henry Manns (one of the escort robbers). The man who got away was Johnny Gilbert, another of the escort robbers and brother of Charles.[31] After his escape Gilbert rode hard for the Weddin Mountains to gather a party to rescue his brother and Manns. The gang gathered weapons, mounted fresh horses and rode through the night to Sproule’s ‘Timoola’ station, where Gilbert judged they were ahead of the police and their prisoners.[32] The bushrangers secured two women and a couple of travellers at the station and waited for the police to arrive. As Pottinger’s party, with their captives, approached 'Timoola' homestead, with Sergeant Lyons in the lead, three or four men suddenly rushed from the dense scrub beside the road. The men had blackened faces and red caps, "each armed with a double-barrelled gun and a brace of revolvers". They called out "bail up" and began firing. Pottinger and Mitchell, in the rear, were set upon by three others, similarly attired. Lyons’ horse was struck by a ball and reared up, unseating the rider, and galloped into the bush with Lyons' revolver attached to the saddle. Three men rushed forward and released the prisoners. Pottinger and Mitchell returned fire, but against overwhelming odds and disciplined gunfire from the bushrangers, they began to retreat back along the road. With their ammunition "all but expended" Pottinger and Mitchell galloped back to the station they had left earlier, in possession of the recovered gold. The bushrangers had been temporary restrained from pursuing them; their horses, tied to a nearby paling fence, had taken fright during the gunfight and ran off into the bush. By the time they returned to 'Timoola' that evening, the bushrangers were long gone. They were heartened to find that Lyons had managed to escape into the bush and was uninjured.[30]

On July 27 Pottinger led a party of troopers who went to the Wheogo district and apprehended Maguire and Dan Charters at Maguire's place, and also Ben Hall and his brother William at Ben Hall's place (half a mile distant from Maguire's). Another man, John Brown, was also apprehended at another locality in the district.[28] At the Forbes Police Court on Tuesday, 5 August 1862, the four men from the Wheogo district, Ben Hall, John Maguire, John Brown and Daniel Charters, together with William Hall (Ben's older brother, described as a miner from Forbes), were brought before the court on suspicion of being involved in the escort robbery near Eugowra. Police Inspector Pottinger asked that the prisoners be remanded to await the appearance of a witness to identify bank-notes found in possession of one of their number and claimed by William Hall as his property. Pottinger opposed bail for all, with the exception of Charters "of whom he had nothing to say". Charters was allowed bail of £500, with two sureties of £250 each, to appear when called upon. The other prisoners were remanded in custody for a further seven days.[33] Charters became an informant, hoping to receive a full pardon. He named the participants in the gold escort robbery, but did not implicate Ben Hall or Jack O'Meally. Hall was granted bail in late August of £500 and two sureties of £250.[34]

In mid-August 1862 Senior-sergeant Sanderson returned to the Weddin Ranges district and arrested Fordyce at Patrick O'Meally's inn. John Bow was arrested by Pottinger on August 21.[28] John Bow and Alexander Fordyce (charged with the escort robbery) and Jack O'Meally and Maguire (charged with being accessories) were brought up at the Forbes Police Court on Monday, 22 September 1862, and remanded in custody.[35] O'Meally and Maguire remained in custody, chained to one another and "carried from one lock-up to another", while the police tried to gather evidence linking them to the gold escort robbery. In the end, Maguire was charged and O'Meally was released.[36] On November 27 Maguire, Fordyce and Bow were charged "with being concerned in the escort robbery" and committed to stand trial.[37] On 1 December 1862 Henry Manns was apprehended at Murrumburrah by Constable Moore "on suspicion of highway robbery". Inspector Pottinger, who happened to be nearby at Lambing Flat, identified Manns a day or two later as one of those forcibly released from his custody near 'Timoola' station in July.[38]

A 'Special Criminal Commission' was held in February 1863 at the Sydney Criminal Court in Darlinghurst to try the four accused gold escort robbers, John Bow, Alexander Fordyce, Henry Manns and John Maguire. After a trial that lasted four days, on Thursday, 26 February 1863, a jury found Maguire not guilty. However, the other three – Fordyce, Bow and Manns – were found guilty of feloniously wounding Sergeant Condell immediately prior to the robbery near Eugowra.[39] Each were sentenced to death, but after petitions pleading for reprieves, the sentences of John Bow and Alex Fordyce were commuted to life with hard labour on the roads, the first three years “in irons”.[40] The pleas for Henry Manns were in vain; he was hanged at Darlinghurst Gaol on 26 March 1863.[41]

Bushranging resumes

At eight o'clock in the evening of 2 February 1863 five armed men entered George Dickenson's store at Spring Creek near Young and stuck-up Dickenson, his storekeeper and a customer. The men were recognised as Johnny Gilbert, Jack O’Meally, Patsy Daley (O'Meally's younger cousin) and Christie Boland (alias Purtell).[42][43] The fifth man was believed to be Ben Hall.[44] The three detainees were taken outside and guarded at gunpoint by Daley while the other bushrangers searched the store. As others passed by they were detained as well. It was reported that Daley was "very nervous and trembled like a leaf"; noticing his unease several of the captives pressed forward at which point Hall intervened and warned them to stay back.[45] After searching the store the bushrangers departed with £5 in silver, an estimated £10 worth of gold-dust, a revolver, three watches, several pairs of boots and a quantity of clothing.[46] As they were leaving an unarmed policeman in plain clothes, Constable David Stewart, came along. The bushrangers ordered him off his horse. The policeman resisted and he was pulled off, and his horse, saddle and bridle were taken.[47]

Murder of Adolph Cirkel

On Sunday, 15 February 1863, between six and seven in the evening, two men arrived at the Miners' Home Inn at Stoney Creek, near Lambing Flat. After fastening their horses, the men entered the bar and ordered 'nobblers'.[48] The identity of the two men has been the subject of speculation, but the taller man was certainly Jack O’Meally and his shorter companion was probably either Ben Hall or Johnny Gilbert.[3] The two bushrangers soon made their intentions known, by bailing up those in the bar and stealing the contents of the till. Soon afterwards the publican, Adolph Cirkel, who had been in the nearby bakehouse, entered premises by the front door. O'Meally told him to go to the corner of the room with the others who were being detained, but Cirkel, a strong and determined man, resisted and began to struggle with O'Meally. It was reported by witnesses that the other bushranger called out, "Blow his bloody brains out" and "Shoot the bugger", at which O'Meally fired his pistol, the ball striking Cirkel above his left ear and killing him instantly. The two bushrangers then rushed from the house, mounted their horses and departed from the scene.[48]

Mid-afternoon on Saturday, 21 February 1863, four armed bushrangers dressed "in the style of policemen in private clothes" rode up to Meyer Solomon's store at Little Wombat.[49] They were Ben Hall, Johnny Gilbert, Jack O'Meally and Patsy Daley.[44] Solomon's heavily pregnant wife observed the men approaching and informed her husband, who reached for a musket. Meeting them at the door Solomon fired his musket, the ball grazing the neck of one of the bushrangers "and tearing the collar of his coat". The intruders responded by firing two shots in return. Solomon escaped through the back of the premises; he was pursued by two of the men, captured and brought back to the store and placed under guard with his wife and a young lad, George Johnstone, in Solomon's employment.[47] During the robbery the bushrangers warned Solomon by referring to the murder of Cirkel six days previously; they told Solomon “they would serve him like they did the man at Stoney Creek, who was too flash, and blow his bloody brains out, as they did his”.[49] The bushrangers proceeded to ransack the store in "cool, deliberate manner", loading three pack-horses with goods before departing at about seven o'clock in the evening.[49][50] The following morning the police tracked the bushrangers for about ten miles in the direction of the Weddin Mountains, but gave up the pursuit "from the want of a tracker and exhaustion, as most of the police had just returned from Yass".[51]

The detainment of Sub-Inspector Norton

By late February 1863 Sub-Inspector John Norton was given charge of the police at Forbes. On 28 February 1863 Norton and Tracker Billy Dargin were on patrol in pursuit of the bushrangers Hall, O'Meally and Daley; they had arranged to meet ten police troopers at the foot of Wheogo Mountain, north-west of Grenfell, but through a misunderstanding the meeting did not eventuate. Norton and Dargin continued the pursuit and the next morning, March 1, while riding towards 'Pinnacle' station they came upon the camp of the three bushrangers, who immediately mounted their horses and spread out on either side of the road in an effort to encircle Norton and Dargin. O'Meally advanced to within 80 to 100 yards and fired two shots at Norton from a double-barrelled gun. The bushrangers pushed forward to within fifty yards, exchanging shots with Norton, with none taking effect. When the policeman's ammunition was expended Daley, "armed with three revolvers and a pair of pistols", rode up to him and told him to throw down his arms. During the shooting Dargin had dismounted and escaped on foot into the bush, with several shots fired after him. Norton claimed that after his surrender "Hall rode up and fired point blank at him, but fortunately without effect". While O'Meally guarded the prisoner, Hall and Daley started in pursuit of the tracker, without success.[52]

When Hall and Daley returned to their prisoner, it was found that Norton had been mistaken for Trooper Hollister who, it was claimed, "had threatened to shoot Ben Hall". After being confined for three hours Norton was allowed to depart with the police horses. The writer for the Lachlan Observer newspaper (Forbes) considered that the Sub-Inspector owed his release "to his being a 'new chum' in the district, and the fact of his having a wife and family in Sydney". After his escape the tracker Dargin made his way to the Pinnacle police station where he reported the events. Sub-Inspector Norton arrived back at Forbes on March 3.[52]

With Gilbert

On Thursday, 30 July 1863, Gilbert and O’Meally were thwarted in their attempt to rob the Commercial Bank at Carcoar in the middle of the day, managing to escape from the town when the alarm was raised before they could carry out the robbery. That evening the pair robbed Stanley Hosie’s store at nearby Caloola, taking cash and a number of articles of clothing, including silk dresses, boots and shoes which they said they wanted for “their people”. At one stage Hosie challenged either of the bushrangers to lay down his arms and engage him in a “fair fight”; the bushrangers smiled at this and one said, “No mate, we don’t do business in that way”.[53][54]

On Thursday afternoon, 6 August 1863, three prisoners named Thomas Morris, Charles Green, and James Burke, were being conveyed from Carcoar to Bathurst on the mail coach.[55] The prisoners, under the custody of Sergeant Morrisset and three constables, were supposed to be ‘bush telegraphs’ (sympathisers who kept bushrangers informed of police movements).[56] The three prisoners were inside the coach, along with constables Grainger and Merrin; Sergeant Morrisset sat on box with the driver, with a female passenger between them, and Constable Sutton was following on horseback at the rear. Soon after departing, as they neared the Five Mile Waterholes, a dray was seen on the road ahead. Three horsemen came galloping towards the coach, two of whom were recognised as Gilbert and O’Meally. Gilbert and the third man rode to each side of the coach and O’Meally came to the front of the horses, shouting at the driver to "bail up". As the coach came to a stop Morrisset jumped from the box and he and the constables in the coach began to exchange fire with the bushrangers. Gilbert and O’Meally "carried on the contest", advancing and receding as they fired at the police, "and it is said they exhibited extraordinary expertness in the management of their horses – at times dropping at their sides, and then ducking down to the pommel, as they received and exchanged shots". At one point Constable Sutton rode between the two and aimed his revolver at O'Meally, but the bushranger raised his carbine and fired first, the bullet entering Sutton's elbow and exiting at his collar-bone.[55] During the gunfight a bullet hit O'Meally’s watch, saving him from a wounding or death. After the incident the bushranger "kept the relics of the watch as a kind of 'charm' or amulet against police bullets".[57] After Gilbert's horse was struck by a bullet, the bushrangers rode off. The wounded trooper was taken to Blayney and the coach proceeded to Bathurst. Dr. Machattie travelled to Blayney to treat Sutton and the next day brought him to Bathurst, reporting that his patient "was progressing favourably".[55] Newspaper reports speculated that the reason for Gilbert and O’Meally’s attack on the mail coach was to free the prisoners from police custody. However, John Vane, who had agreed to join Gilbert’s gang about a week before this incident, claimed in his biography (published in 1908) that the bushrangers had intended to rob the mail coach and the presence of policemen had taken them by surprise.[58] The third bushranger was initially identified as John Vane, but he was later tried and acquitted of being involved in the attack. Vane’s own account describes the third man as “a resident of the locality”.[58]

Young district

On 13 August 1863 "a band consisting of four finely mounted robbers, headed by Gilbert" was seen in the neighbourhood of Marengo, 15 miles east of Young.[59] Gilbert, O'Meally, Vane and Mick Burke (a new recruit to the gang) joined with Ben Hall at his campsite on 'Mimmegong' station (now known as 'Memagong'), west of Young. In his biography Vane states that, from when the bushrangers met up, Hall "became our leader".[60]

On 16 August 1863 a police patrol which had been hunting for the bushrangers, led by Inspector Frederick Pottinger and consisting of three troopers and two Aboriginal trackers, came across the tracks of five horses south of the Weddin Mountains. They followed the tracks until dark. The next morning, after "incessant rain" during the night, they came upon the riders. The bushrangers, seeing the police, galloped off and escaped on their "superior horses". Pottinger and his men had come within three hundred yards of the gang and were able to identify Gilbert, O'Meally, Hall, Vane and Burke.[61] Pottinger’s trackers followed the bushrangers’ trail to their camp on 'Mimmegong' station.[62][63] The bushrangers had formed two separate camps on 'Mimmegong' about a mile distant from each other, one for the day another for the night, and the trackers had found the night-camp where some of the bushrangers' horses were tethered. Hall and Vane, on returning to the day-camp, had seen the fresh tracks of shod horses heading in the direction of the night-camp and concluded “that the police were about”. Wishing to retrieve some of their horses, however, the gang cautiously approached the night-camp and, while the others waited in hiding, Vane rode up and began to put a bridle on one of the horses. From his concealed position Pottinger called out "Stand!", upon which the bushrangers began firing, with the police returning fire. Vane ran back to his horse and was in the process of mounting it when he was shot in the calf. Despite his wound Vane mounted the horse and escaped. O’Meally, who had approached from the opposite side, had managed to secure a horse and the five bushrangers then galloped through the scrub and onto a flat, when they turned and kept their pursuers at bay with their rifles, having a longer range than the police revolvers.[64] On the night of 18 August 1863, the bushrangers called at Roberts' 'Currawang' station in the Black Range, south of Marengo, and stole "four or five" of the best horses from the stables. Roberts had been engaged by the police to muster, select and break in horses "for the express purpose of bushranger-hunting".[65] After the confrontation with Pottinger and his party the bushrangers camped in the dense scrub near Bald Hill, north-west of Young, while Vane recovered from his wound.[66]

During the morning of 24 August 1863 Gilbert, O'Meally, Hall, Vane and Burke stuck up and robbed several people on the Hurricane Gully Road between Young and the Twelve-mile Rush. Amongst those who were robbed were four storekeepers travelling to the diggings to collect accounts. The storekeepers were not carrying money, but the bushrangers took their horses, saddles and bridles.[67][68] After camping in the Black Range for several days the gang separated. Gilbert, Hall and Burke headed to Burrowa while O'Meally and Vane remained at James O’Meally’s place in the Black Range, with the arrangement they would meet up again at 'Demondrille’ station near Murrumburrah.[69]

On Saturday evening, 29 August 1863, O'Meally and Vane stuck up 'Demondrille' station, stealing a revolver, a saddle and bridle, four bottles of "pale brandy" and other articles from the superintendent of the station, John Edmonds.[70][71][69] After the robbery the two bushrangers stopped at a slab hut two and a half miles from 'Demondrille' homestead, occupied by Walter Tootal, his mother and two younger siblings, as well as a carrier named George Slater.[72] Vane described the visit as "a friendly one, and the brandy was brought into requisition". In the meantime, after information of the armed robbery was received at Murrumburrah, Senior-constable Haughey and Constable Keane joined with two policemen from Wombat and rode towards the station. In the early hours of Sunday morning the four troopers, having arrived at 'Demondrille' and acting on information received from Edmonds, went to Tootal’s hut and saw four horses tied up outside (three of them saddled). Mounted-constable Churchman approached the hut and called on those inside to come out; the door was opened momentarily and then closed again. Suddenly shots were fired from the hut, wounding the policemen’s horses and hitting Haughey in the knee. O’Meally and Vane emerged from the hut, exchanging fire with the police in the darkness. O’Meally reached their horses but one broke away in the confusion, leaving Vane to escape into the surrounding bush on foot.[73][74]

Murder of John Barnes

After his escape from Tootal’s hut, O’Meally rejoined Gilbert, Hall and Burke who were camped a short distance away. A horse was then brought for Vane, but, as the gang was a horse short, later that morning Gilbert and O’Meally rode off in search of one.[75]

At about midday on 30 August 1863 a Murrumburrah store-owner named John Barnes, accompanied by John Hanlow, an assistant-storekeeper, were riding near 'Wallendbeen' station, travelling from Murrumburrah to Cootamundry, when they were bailed up by O'Meally and Gilbert. The bushranger told Barnes, "get off, I want that horse"; instead of dismounting, however, the storekeeper wheeled the horse around and galloped towards the station homestead. O'Meally fired his revolver at Barnes and then galloped after him, firing three more times. Between a stockyard and the homestead Barnes fell from his horse, with three bullet wounds to his body and his head hitting a stump as he fell. The squatter, Alexander McKay, emerged from the house and O’Meally ordered him to the station store where he selected boots, a coat and hat, the bushranger explaining it was "for my mate, for he lost them last night in a skirmish with the police". Afterwards, Hanlow, McKay and O’Meally went to where Barnes had fallen, finding him dead on the ground. O’Meally said: "I am sorry for him – it was his own fault – he ought to have stood, and he would not have been shot". O’Meally and his companion then departed, taking Barnes’ horse.[76]

After this incident the gang returned to the Young district, camping on 'Mimmegong' station to the west of the township. Gilbert, Hall and Burke remained only a few days, leaving O’Meally and Vane at 'Mimmegong'.[77]

On Friday, 4 September 1863, O’Meally and Vane stuck-up McGregor’s store on Humbug Creek in The Bland district. During the robbery William Campbell, a magistrate of Burrowa, rode up and was greeted by Vane (mis-identified in the newspaper report as Gilbert). The bushrangers took a quantity of clothing and other property from the store and Campbell’s gold watch and chain.[78][79]

On the evening of 10 September 1863 O’Meally and Vane entered Eastlake’s store at the Twelve-mile Rush at Burrangong (west of Young). O’Meally presented his revolver at the storekeeper who immediately dropped behind the counter and called out for assistance. In response O’Meally fired his revolver, the bullet hitting the shelves and the flash extinguished the candle. Vane went to a backroom where another man was in the act of taking down a revolver from the mantelpiece. Disarming the man Vane returned to the store. Meanwhile, in the darkened room, the storekeeper had crawled to the end of the counter and gained access to a gun. He fired at Vane, with the bullet passing between Vane’s arm and his body. O’Meally and Vane hurriedly left the store, mounted their horses and headed towards the nearby Ten-mile Rush. At the outskirts of the settlement they entered Neasmith’s store and held up Mrs. Neasmith, during which the robbers were described as being "quite cool and jocular". After gathering a number of articles from the store, a customer entered from whom they took a bag which contained (according to Vane's biography) £60 in notes and seven ounces of gold. Soon afterwards the bushrangers departed, returning to their "camp in the scrub".[80][81] After about a week at the camp O’Meally and Vane loaded up two pack-horses with stolen store goods ("chiefly drapery"), intended as gifts for their friends and sympathisers, and travelled back to the Carcoar district.[82]

The burning of Patrick O'Meally's house

A fortnight after the murder of John Barnes at 'Wallendbeen' station, the police burned down Jack O'Meally's parents' home in the Weddin Mountains, previously a public house. Even though 'Arramagong' station had been sold in July 1861, Patrick O'Meally, his wife Judith and several of their children had continued to occupy their house on the property, against the new owner's wishes.[3] On 14 September 1863 a party of police led by Sub-Inspector Roberts arrived at Patrick O'Meally’s ex-public house in the Weddin Mountains. After searching the house the police told O'Meally to "clear himself, family and chattels out of the house" as they intended to burn it down. The old man refused, saying, "The police have often threatened to burn us out but they have never done it yet, and I do not believe they ever will". At this the sub-inspector took a fire-stick from the hearth, took it outside and "commenced the work of destruction". Before very long "nought remained of the once substantial inn but a heap of charcoal and smoking embers". After the house was destroyed, for a time the family lived nearby in a tent.[83]

The response in the colonial press to the burning of Patrick O'Meally’s house was scathing, labelling the act as "the distinguishing characteristic of a weak government". The Marengo correspondent to the Yass Courier commented: "People around here say that as some police inspectors find themselves incompetent to take the leading bushrangers, they therefore vent their disappointment and rage upon the robbers' relatives, i.e, by rendering houseless their aged parents, wives, and children".[83]

Carcoar district

On Tuesday, 22 September 1863, word reached Gilbert's gang, from one of their 'telegraphs', that three troopers were on patrol on the road towards Carcoar in the vicinity of Mount Macquarie. Gilbert, O'Meally, Vane and Burke set off in pursuit; following their tracks they observed the troopers had called at the hut of a man called Marsh. As they approached the hut the three policemen and Marsh emerged, but were taken by surprise by the four bushrangers, disarmed and tied to a fence. They were released after several hours, the bushrangers having taken the troopers' horses, saddles and bridles, as well as their firearms and handcuffs.[84][85]

Late on Wednesday afternoon, 23 September 1863, Stanley Hosie's store at Caloola was stuck up by Gilbert, O'Meally, Vane and Mick Burke (for the second time within two months). They secured Hosie with handcuffs taken from the three troopers they robbed the day before, and then rounded up the blacksmith and another man living opposite and the village shoemaker, handcuffing all three. The bushrangers then proceeded to ransack the store, pulling things from the shelves and causing much damage. They told Hosie "they did this as a punishment for his having given information to the police of their former visit to them". In the paddock adjoining the store the bushrangers managed to catch two horses, and "being unable to catch the others, deliberately shot them". They loaded the horses with the goods they wished to keep and left. The bushrangers then "adjourned to an inn close by, and there caroused until a late hour".[86][87]

On Friday evening, 25 September 1863, John Loudon's household at 'Grubbenbong' station, fifteen miles from Carcoar, was robbed by the gang of bushrangers, Gilbert, Hall, O’Meally, Vane and Burke. The bushrangers arrived at about ten o’clock and forced their way into the house at gunpoint. The members of the household were taken to the verandah where Loudon and some of the men at the station were handcuffed and Loudon’s wife and "the other females" were given chairs to sit on. After ransacking the house the bushrangers "ordered supper", and had ham and eggs cooked for them. Later “Vane amused the party by playing the piano”. The bushrangers remained at the station for about four hours before departing in the early hours of the morning.[88][89][90]

Late on Saturday morning, 26 September 1863, the bushrangers arrived at William Rothery’s 'Cliefden' station at Limestone Creek, south-west of Carcoar, where they bailed up the occupants and "partook of dinner – regaling themselves with champagne and brandy". Hall and Gilbert rode down the paddock and ran the station horses up to the yard where three were selected and saddles and bridles procured.[88][91][92] From Rothery’s the bushrangers proceeded to Canowindra (after having informed Rothery of their intended destination), arriving at the township at six o’clock in the afternoon. They firstly detained Constable Sykes, the only policeman stationed at Canowindra, and took him to Robinson’s public-house. O’Meally and Burke remained at the inn while Hall, Gilbert and Vane “went on a foraging expedition” to the two stores in the township, belonging to Pierce and Hilliar, taking a quantity of men’s clothing and three pounds in cash. They then adjourned to Robinson’s house and ordered tea. The publican and his wife had departed for Bathurst, leaving Robinson's sister and "the two Miss Flanagan's in charge of the house". After they had eaten “Gilbert very politely requested one of the young ladies to play him a tune on the piano”. Later in the evening a dance was proposed, which "continued till daylight the next morning". A number of the town's residents had also been brought to the public-house and it was reported that "the night’s amusement" was "spoken of as one of the jolliest affairs that has ever taken place in that small town".[88] In the morning Hall, Vane and Burke rode to 'Bangaroo' station in search of horses, but finding none, returned to Canowindra where Gilbert informed them that troopers were camped on the opposite side of the Belubula River, now in full flood, waiting for the waters to subside. With the exception of Burke, the bushrangers crossed the flooded stream and camped on a hill overlooking the town. Burke crossed the next morning after the waters had dropped, after which the gang rode into "very rough country" to evade the police.[93]

Bathurst and surrounds

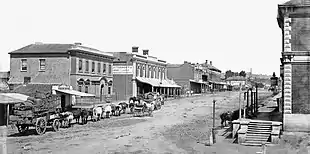

Early on Saturday evening, 3 October 1863, Gilbert’s gang of bushrangers rode into Bathurst, the most populous township west of the Blue Mountains and headquarters of the Western police force. Saturday night was the ‘market night’ for the town, where the shops around the town square were open for business. Vane kept watch in the darkness near the Telegraph Office while the others went shopping in William-street. They stopped at the shop of Pedrotta, the gunsmith, hoping to obtain revolving rifles, but were informed none were presently available. Proceeding a few doors down Hall and Gilbert entered McMinn’s jeweller’s shop with guns drawn, while O’Meally and Burke waited in the street outside. In the shop McMinn’s daughter started to scream and several of those in the street became aware of the situation and raised the alarm. Realising the situation had gotten out of hand, Hall and Gilbert “beat a retreat”. Having left the shop and remounted their horses, they galloped back along William-street. At the Howick-street corner, Hall and another of the riders turned and the others, appearing to have become uncertain of their way, continued in a direction leading to the police barracks. Hall fired his revolver in the air, causing his companions to turn. By this time Vane had also joined them and the bushrangers crossed over into George-street. As they passed the corner with Piper-street they saw John de Clouet’s public-house, the Sportsman’s Arms. De Clouet owned a racehorse named 'Pasha' which Gilbert coveted, so he, Vane and O’Meally dismounted and entered the rear of the yard. Finding the stable locked they went to the house and bailed up De Clouet and his wife, taking from them £10 and two watches. By this time police had been seen galloping along George-street, so they remounted and started making their way out of the town. The bushrangers were spotted by troopers and fired upon, but managed to escape.[94][95][96]

On the evening of 6 October 1863 Gilbert’s gang raided several places along the Vale Road, leading south from Bathurst. To start with they paid a visit to a store kept by the widow, Mary Mutton, only half a mile from the township, where they demanded money but were assured there was none. While searching the bedroom with a candle for light, Gilbert set fire to the bed-curtains (he claimed by accident). O’Meally and Vane rushed in and Vane put out the flames, but burnt his hands in the process. He later recalled that “the old lady was very kind when she saw what had happened, and got me some Holloway’s ointment to dress the burns, at the same time remonstrating with us for pursuing such evil courses”.[97] The Mutton family story is consistent with Vane’s recollection except for one significant detail: that it was Gilbert, not Vane, who extinguished the flames and burnt his hands.[98] The next place the bushrangers called at was Walker’s public-house, a mile further on, where they obtained only a few notes and some silver coins, as well as an old horse-pistol. The next place was McDiarmid’s store, where they bundled groceries and other goods into pillow-cases. A mile down the road was the Hen and Chickens Hotel, kept by Henry Butler, where once again there were meagre rewards.[99][97]

The affray at 'Dunn's Plains'

On the evening of Saturday, 24 October 1863, the bushrangers Johnny Gilbert, Jack O'Meally, Ben Hall, Johnny Vane and Mick Burke approached the house of Henry Keightley, at 'Dunn’s Plains' near Rockley. Keightley, an assistant Gold Commissioner, was about thirty yards from the house when the gang rode up and ordered him to "bail up". Rather than obey the order Keightley ran towards the house, as the bushrangers fired at him. When he was inside the house, he and a guest, Dr. Pechey, guarded the door with a double-barrelled gun, of which only one barrel was loaded, and a revolver. The bushrangers fired at the men from cover. Burke crept up the side of the house and, swinging his arm around, fired at the defenders as they stood at the doorway. Keightley waited for Burke to show himself; when he next appeared, "incautiously exposing his body", he was shot in the abdomen, causing him to stagger to the side of the house. Burke was heard to say, "I’m done for, but I’ll not be taken alive", and tried to shoot himself with his revolver. The first shot grazed his forehead and the next "blew away a portion of his skull", whereupon he fell to the ground. The other bushrangers continued to fire from cover. At one stage Dr. Pechey attempted to cross the yard to a kitchen where another gun could be found, but he encountered Vane, who ordered him back and fired after him. The two defenders then climbed to the roof through a skylight and Keightley exchanged shots with Vane in the yard below. Ben Hall called out that they would burn the house if they did not come down. With Keightley's wife and child sheltering in the house, the two men relented and agreed to surrender. After they descended, an infuriated Vane struck Dr. Pechey with the butt of his revolver, knocking him to the ground.[100][101]

Keightley was now in a precarious position. With his friend lying gravely wounded, Johnny Vane grabbed Keightley’s gun and loaded it. In anger Vane told them that "Burke and he had been brought up as boys together, that they had been mates ever since, and that the gun that had deprived him of life should in turn take the life of the man who killed him". Caroline Keightley, "in frantic agitation", implored Hall and Gilmore to save her husband's life, at which Hall called on Vane to desist. Gilbert and Hall then decided that "as the Government had placed five hundred pounds upon Burke’s head, the amount of the reward should be handed over to them". They agreed to allow until two o'clock the following day "for the production of the money". Dr. Pechey examined Burke, who was still breathing but unconscious, and said there was little he could do without his instruments. The doctor was permitted to go into Rockley to get what he needed, "having first pledged his honour that he would not raise the alarm". O'Meally had been tending to the horses during these negotiations. When he returned, O'Meally rejected the ransom proposal "and declared his intention to revenge the death of his companion", but eventually he was "pacified by the others". While they awaited Pechey's return the bushrangers went into the house and "drank some spirits and wine". By the time Dr. Pechey returned from Rockley, Burke had died.[100][101]

Arrangements were then made for payment of the ransom. Caroline Keightley and Dr. Pechey were to go into Bathurst for the money. If there were any indication of the police being notified the bushrangers vowed to shoot Keightley immediately. Their captive was taken to a nearby hill called Dog Rocks, which overlooked the road. Pechey and Mrs. Keightley rode the 24 miles to Bathurst, arriving at about four in the morning. They went to Caroline’s father, Henry Rotton, who had the Commercial Bank opened for him so he could procure the required money. Rotton and Dr. Pechey then travelled back to 'Dunn’s Plains' where the doctor handed over the ransom and Keightley was set free.[100][101]

While they had been waiting for the ransom the bushrangers arranged with men from a neighbouring station to take Burke's body on a spring cart to his father's house, for which they were paid two pounds each. Two days later troopers from Cowra met the men conveying Burke’s body, took charge of the cart and conveyed the body to Carcoar so an autopsy could be carried out.[100]

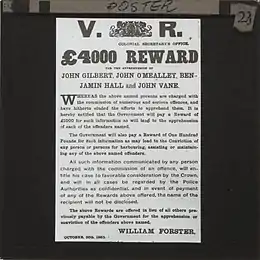

After the death of Mick Burke, the colonial government increased the reward to one thousand pounds each for information leading to the apprehension of the remaining gang members, John Gilbert, John O’Meally, Ben Hall and John Vane, "charged with the commission of numerous and serious offences".[102]

The attack on 'Goimbla' station

Just before nine o’clock in the evening of 19 November 1863, the squatter David Campbell, of 'Goimbla' station on the Eugowra Creek, was seated in his dining room when he heard footsteps on the front verandah. Campbell grabbed a gun and met a man at the doorway of his bedroom, who fired a double-barrelled gun at the squatter and Campbell fired his gun in return. The intruder ran around the corner of the house to join his two comrades at the front door. Campbell’s wife Amelia went to the dining room and retrieved a spare gun and ammunition, which, under fire from the bushrangers, she brought to her husband who had sought refuge in a bedroom.[103] After she had brought the firearm to her husband, Amelia Campbell left by the back of the house and, in the darkness, crossed a paddock about a hundred yards to a hut where four servant men slept, in order to seek their assistance. However the men refused to become involved; no arguments on her part could convince the men to leave the hut and render assistance against the bushrangers. While Amelia was returning alone to the house "the vulture eye of Gilbert caught sight of her"; he ordered her to stand "or he would blow her brains out", but the woman "paid no attention to the threat" and hurried on in the darkness, making her way to the house.[104] With his guns loaded, David Campbell went through the house to the back door and took up position between the main house and the kitchen. After she returned from the men's hut, Mrs. Campbell and a servant girl joined Campbell behind the house. A number of shots were fired at the front door, with repeated calls to surrender. After several more shots were fired by the bushrangers from different directions, one of them called out, "If you don’t immediately surrender, we will burn your place down!". Soon afterwards flames were seen, arising from the barn and stable about thirty yards from the house.[103]

With the light increasing as the barn burned, it was observed that the bushrangers were crouched in a field of oats behind a paling fence about forty yards from the front of the house. Amelia Campbell drew her husband's attention to a man in a cabbage-tree hat, looking over the fence in the direction of the burning barn. Campbell ran to the end of the house, and from the front corner, took deliberate aim at Jack O'Meally, the man in the cabbage-tree hat, and fired his gun. While Campbell reloaded, several shots were fired but it appeared to him the bushrangers were retreating.[103] Before leaving the station, the bushrangers retreated to one of the huts, where a female servant heard them "cursing and swearing in a most fearful manner that they would have their revenge". In a letter to her mother after the events of that night, Amelia Campbell disclosed that the servant "heard one of them regretting not having shot the woman, – meaning, I suppose, myself, – but his comrade called out to him to hold his tongue, and mind what he was about".[105]

When the shooting had begun at 'Goimbla' homestead, David Campbell's younger brother, William, was in his bedroom. He rushed out the back door onto the verandah, where he encountered a man who shot at him twice in quick succession. The first struck him in the chest, causing him to stumble and fall.[103] William had received "a charge of slugs in the breast, four wounds in all, but fortunately not deep".[105] When he recovered he made his way through the back gate to the oat field at the back of the barn, where he observed from a distance the volleys of gunfire and the burning of the barn. After a while, after all was quiet, Campbell proceeded on foot to the Eugowra police station to alert the police.[103]

At the homestead after about half an hour after the shooting had ceased, by which time it was half-past eleven o'clock, David Campbell cautiously approached the spot where he had shot at the man, where he found a single-barrelled carbine rifle and a cabbage-tree hat behind the fence amongst the oats. The men in the huts "had now recovered from their panic"; Campbell stationed them at various places and they kept watch until morning. The police arrived at dawn.[105] Campbell and Constable Fagan returned to the spot and, following a track through the oats they found O'Meally’s body with a bullet wound in his neck, about ten yards from the fence.[103]

Burial

Jack O'Meally was initially buried on 'Goimbla' station, at a location about fifty yards from the homestead. After ten days, however, O'Meally's father and brothers came to 'Goimbla' to retrieve the bushranger's body. The corpse was exhumed and reburied in the cemetery at Gooloogong, south-west of Canowindra, where other members of the O'Meally family were interred. The burial plot, located between the back of the saleyards and the river, is no longer a cemetery and the graves are unmarked.[106]

Aftermath

On Wednesday, 2 December 1863, a public meeting was held at the Forbes Court-house, attended by "a considerable assemblage of the most respectable and influential of the townspeople and stockholder of the Lachlan", which voted to present a testimonial and address to David and Amelia Campbell in a token of "the appreciation of the public of their courageous and exemplary conduct in resisting the bushrangers during their recent attack upon their household at Goimbla". The Police Magistrate, Mr. Farrand, addressed the meeting; describing the Campbells as "a brave man and a true-hearted woman", he commended their "courageous stand" that had delivered "a serious blow and sore discouragement to the band of ruffian freebooters, who, for a considerable period, had kept the Western districts in continuous alarm". At the meeting a purse of sovereigns was also contributed "as a testimonial to the servant girl at Goimbla, who had manifested great personal daring throughout the contest, and whose conduct was worthy of the highest praise".[107][108]

On 2 March 1864 a public meeting was held in the Chamber of Commerce in Sydney, to decide on the best method of "expressing approval of the gallant conduct" of David Campbell of 'Goimbla' "in repelling the attack of the bushrangers upon his station, and by the death of O'Meally breaking up the gang that so long infested the Western districts". The meeting was chaired by Thomas Holt, the Speaker of the Legislative Assembly, and attended by other politicians and gentlemen of influence (though overall the meeting "was rather thinly attended"). In his opening address the chairman noted that "since the death of O’Meally, scarcely anything had been heard about the rest of the gang". The meeting passed a resolution to form a committee and leave subscription lists at various banks and newspaper offices, "towards a testimonial to Mr. Campbell". It had been estimated that Campbell made an overall loss of between six and seven hundred pounds from the attack on his station, through the destruction of his barn and stable, as well as the losses to his tobacco and hay crops "for, after the affair, he could get no labourers to come near the place".[104]

Great hopes were held that the death of John O'Meally would lead to the breaking up of the gang of bushrangers, variously described as being led by either John Gilbert or Ben Hall. One of the gang members, Johnny Vane, had surrendered to the authorities on the same day that his former comrades attacked 'Goimbla' station, leading to O'Meally's death.[109] Vane had become disillusioned after the death of his childhood friend, Micky Burke, on October 24 at 'Dunn's Plains'.[101] However, the optimism following O'Meally's death proved to be premature. Gilbert and Hall gathered new gang members and remained at large and active for the next eighteen months, though both eventually met violent deaths (Hall on 5 May 1865 and Gilbert eight days later on May 13).[110][111]

In December 1875 the New South Wales government made a special issue of gold and silver medals in recognition of the bravery displayed by the recipients during the bushranging era of the 1860s. Amongst those who were awarded gold medals were Henry Keightley, "who killed the bushranger Burke" at 'Dunn’s Plains' in October 1863, and David Campbell, "who shot bushranger O’Meally" at 'Goimbla' in November 1863.[112]

References

- Notes

- "Escort Rock Gold Robbery". Monument Australia. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- MacAlister (1907), page 276.

- Mark Matthews. "The Gang: John O'Meally". Ben Hall Bushranger. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- Family records, Ancestry.com.

- Lachlan, New South Wales Government Gazette (Sydney), 28 May 1847 (Issue No. 47), page 580.

- Claims to Leases of Crown Lands Beyond the Settled Districts, No. 92, Sydney Morning Herald, 4 October 1848, page 3.

- Bathurst Assize Court, Empire (Sydney), 7 March 1854, page 3.

- Early Colonial Days, The Biography of a Reliable Old Native, John McGuire, W. H. Pinkstone, XIII. Eugowra Escort Robbery, Braidwood Dispatch and Mining Journal, 6 October 1906, page 2.

- Certificate by Justices to Authorise the Granting of a License, Patrick O’Maley, Weddin Mount Inn, 18 June 1860, NSW State Archives; Series: 14403; Item: [7/1512]; Reel: 1241 (per Ancestry.com).

- "Story of the Gold Escort Robbery". Eugowra. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 22 December 2008.

- Lambing Flat, Yass Courier, 1 August 1860, page 2.

- The Lachlan, Yass Courier, 12 February 1862, page 2.

- Pastoral Property, Sydney Morning Herald, 20 July 1861, page 3.

- The Bushranger Gardiner, Empire (Sydney), 19 June 1862, page 4.

- White (1900), Chapter VI: 'Gardiner and Piesley'.

- Mark Matthews. "Frank Gardiner". Ben Hall Bushranger. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- Robbery of Mr. and Mrs. Horsington, Empire (Sydney), 1 June 1864, page 5.

- The Late Highway Robbery of £1800, near Wombat, Sydney Morning Herald, 25 March 1862, page 5; republished from the Western Examiner (Orange), 22 March 1862.

- The Australian Bushranging: Eugowra Escort Robbery, Charles White, Goulburn Evening Penny Post, 27 September 1902, page 6.

- Miscellaneous, Empire (Sydney), 19 April 1862, page 3.

- The Bushranging Days, Sydney Mail, 3 November 1920, page 14.

- Susan West (December 2015). "'The Thiefdom': bushrangers, supporters and social banditry in 1860s New South Wales". Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society. 101 (2): 134–155.

- Central Criminal Court, Freeman’s Journal (Sydney), 7 February 1863, page 2.

- The Gold Escort Robbery, Freeman’s Journal (Sydney), 19 July 1862, page 8.

- Further Particular, Empire (Sydney), 24 July 1862, page 8; republished from the Western Examiner.

- Special Criminal Commission, Sydney Morning Herald, 26 February 1863, page 5.

- Mail and Gold Escort Robbery, New South Wales Government Gazette (Sydney), 17 June 1862 (Issue No. 105 Supplement), page 1110.

- Special Criminal Commission, Sydney Morning Herald, 24 February 1863, page 5.

- An Interview With Gardiner, Bathurst Free Press and Mining Journal, 9 July 1862, page 2; reprinted from the Lachlan Observer.

- The Late Escort Robbery. – Capture of Two of the Gang. – Their Subsequent Rescue, Sydney Mail, 26 July 1862, page 6; abridged from the Lachlan Observer, 16 July 1862.

- The Gilbert Family, The Age (Melbourne), 19 November 1863, page 7; reprinted from the Kyneton Guardian.

- Matthews, Mark. "John Gilbert". Ben Hall Bushranger. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- The Lachlan Escort Robbery, Sydney Morning Herald, 14 August 1862, page 8; reprinted from the Lachlan Observer of 9 August 1862.

- Matthews, Mark. "Ben Hall Pt 1". Ben Hall Bushranger. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- Again Remanded, Yass Courier, 27 September 1862, page 4.

- How Bushrangers Are Made in New South Wales, Goulburn Herald, 30 December 1863, page 2.

- Committal of Three of the Escort Robbers, Yass Courier, 6 December 1862, page 2.

- Lambing Flat, Sydney Morning Herald, 12 December 1862, page 2.

- Special Criminal Commission, Sydney Morning Herald, 27 February 1863, pages 4-5.

- Matthews, Mark. "Eugowra". Ben Hall Bushranger. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- Execution of Henry Manns, Empire (Sydney), 27 March 1863, page 5.

- Robbery Under Arms, New South Wales Police Gazette and Weekly Record of Crime (Sydney), 11 February 1863 (Issue No. 6), page 40.

- Albury Police Court: Saturday, April 16, Albury Banner and Wodonga Express, 23 April 1864, page 2.

- Mark Matthews. "Ben Hall Pt 1". Ben Hall Bushranger. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- Old Time Bushrangers: Some Local Characters, by 'Old Ned', Mudgee Guardian and North-Western Representative, 11 April 1912, page 28.

- Goulburn Assizes, Goulburn Herald, 26 September 1863, page 2.

- Committal of Patrick Daley, Yass Courier, 18 April 1863, page 4; republished from the Burrangong Star of 11 April 1863.

- The Murder of Mr. Cirkel, Empire (Sydney), 26 February 1863, page 2; republished from the Burrangong Star, 21 February 1863.

- Sticking Up and Robbery of Mr. Myers Solomon’s Store, Near Wombat, Newcastle Chronicle and Hunter River District News, 7 March 1863, page 3; republished from the Burrangong Star of 28 February 1863.

- Robbery of Mr. Solomon at Big Wombat, The Herald (Melbourne), 14 March 1863, page 7; republished from the Burrowa Times, 26 February 1863 (via the Goulburn Chronicle).

- Telegraphic Despatches, Sydney Morning Herald, 24 February 1863, page 4.

- The Capture of Mr. Inspector Norton, by Bushrangers, Sydney Morning Herald, 9 March 1863, page 3; republished from the Lachlan Observer, 4 March 1863.

- Attempt to Rob the Bank at Carcoar – A Store Stuck Up at Caloola, Empire (Sydney), 4 August 1863, page 2; republished from the Bathurst Times, 1 August 1863.

- Vane & White (ed.) (1908), Chapter XII: 'Attack Upon the Carcoar Bank', pages 58-65.

- Desperate Affray With Bushrangers, Sydney Morning Herald, 11 August 1863, page 5; republished from the Bathurst Times of 8 August 1863.

- Pascal Tréguer (17 January 2021). "'Bush Telegraph': Meanings and Origin". Word Histories. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- MacAlister (1907), page 272.

- Vane & White (ed.) (1908), Chapter XIV: 'Highway Robbery in Earnest. – Working in Two Divisions. – A Brush With the Police', pages 72-75.

- Marengo, Yass Courier, 19 August 1863, page 2.

- Vane & White (ed.) (1908), page 80.

- Telegram from Pottinger to the Inspector-General of Police (tabled by Charles Cowper in Parliament); New South Wales Parliament, Sydney Morning Herald, 19 August 1863, page 6.

- Bushrangers Chased by the Police, Yass Courier, 26 August 1863, page 2; reprinted from the Burrangong Star, 21 August 1863.

- Mark Matthews. "Ben Hall Pt 2". Ben Hall Bushranger. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- Vane & White (ed.) (1908), pages 80-84.

- Marengo, Yass Courier, 26 August 1863, page 2.

- Vane & White (ed.) (1908), pages 85-86.

- Young, Monday, 4 p.m., Bell’s Life in Sydney and Sporting Chronicle, 29 August 1863, page 3.

- Robbery With Arms or Violence, New South Wales Police Gazette and Weekly Record of Crime, 2 September 1863 (Issue No. 35), page 264.

- Vane & White (ed.) (1908), Chapter XX: 'A Kind Woman’s Concern', pages 99-102.

- In regard to the identity of the bushrangers, Edmonds later testified, "I believe them to be Gilbert and O'Maley", but Vane’s biography and subsequent events indicate it was O’Meally and Vane who robbed 'Demondrille' station.

- The Sticking-up at Demondrille, Yass Courier, 9 September 1863, page 2.

- Shooting With Intent, Goulburn Herald, 26 September 1863, page 2.

- The Encounter Near Demondrille, Yass Courier, 9 September 1863, page 2.

- Young, Bell’s Life in Sydney and Sporting Chronicle, 5 September 1863, page 3.

- Vane & White (ed.) (1908), page 106.

- The Murder of Mr. Barnes of Murrumburrah, Sydney Morning Herald, 7 September 1863, page 5.

- Vane & White (ed.) (1908), pages 107-108.

- Sticking-up on The Levels, Yass Courier, 9 September 1863, page 2.

- Vane & White (ed.) (1908), page 108.

- Sticking-up at the Ten and Twelve Mile Rushes, Burrangong, Yass Courier, 16 September 1863, page 2; reprinted from the Burrangong Star, 12 September 1863.

- Vane & White (ed.) (1908), pages 112-115.

- Vane & White (ed.) (1908), pages 116-117.

- Patrick O’Meally’s House Burnt By the Police, The Golden Age (Queanbeyan), 1 October 1863, page 2; original source: the Marengo correspondent of the Yass Courier.

- Bathurst, Maitland Mercury and Hunter River Advertiser, 26 September 1863, page 4.

- Vane & White (ed.) (1908), Chapter XV: 'We Capture Three Police Men', pages 76-77.

- Hosie’s Store at Caloola Again Stuck-up, Yass Courier, 26 September 1863, page 2.

- Outrage at Caloola, The Golden Age (Queanbeyan), 1 October 1863, page 3; republished from the Bathurst Times.

- Bushranging, Empire (Sydney), 6 October 1863, page 2.

- Further Examination of Vane, the Bushranger, Sydney Morning Herald, 8 December 1863, page 3.

- Vane & White (ed.) (1908), pages 135-136.

- The Bushrangers in the Western Districts, Sydney Morning Herald, 7 October 1863, page 5.

- Vane & White (ed.) (1908), pages 136-137.

- Vane & White (ed.) (1908), pages 139-140.

- Audacity of the Bushrangers in New South Wales, Argus (Melbourne), 13 October 1863, page 6; republished from the Bathurst Times, 7 October 1863.

- Gilbert and Three of His Mates in Bathurst, Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, 10 October 1863, page 5; republished from the Bathurst Free Press, 7 October 1863.

- Vane & White (ed.) (1908), Chapter XXXV: ‘The Raid Upon Bathurst. – A Challenge and What Came of It’, pages 123-134.

- Vane & White (ed.) (1908), pages 151-153.

- Bushrangers at Bathurst, Evening News (Sydney), 9 September 1911, page 7.

- Bathurst, Empire (Sydney), 8 October 1863, page 5.

- Desperate Encounter With the Bushrangers, Sydney Morning Herald, 30 October 1863, page 5; republished from the Bathurst Times, 28 October 1863.

- Vane & White (ed.) (1908), Chapter XXXII: ‘The Fight at Keightley’s. – Death of Mick Burke’, pages 167-179.

- Four Thousand Pounds Reward, New South Wales Government Gazette (Sydney), 26 October 1863 (Issue No. 207 Supplement), page 2313.

- The Death of O’Meally: Magisterial Enquiry, Sydney Morning Herald, 27 November 1863, page 4; from the correspondent of the Bathurst Times.

- Testimonial to Mr. H. D. Campbell, of Goimbla, Sydney Morning Herald, 3 March 1864, page 5.

- The Bushrangers at Goimbla, The Herald (Melbourne), 2 December 1863, page 3; letter from Amelia Campbell to her mother, originally published in the Sydney Morning Herald.

- Peter Soley (29 November 2013). "Mystery over outlaws graves an old story". The Grenfell Record. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- Public Meeting, Sydney Morning Herald, 9 December 1863, page 8.

- The signed testimonial is held in the collection of the Museum of Australia; see also: "Amelia Campbell's coffee urn". National Museum of Australia. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- Vane & White (ed.) (1908), Chapter XXXV: 'I Surrender to a Priest', pages 188-193.

- The Death of Ben Hall, Sydney Mail, 13 May 1865, page 9.

- The Death of Gilbert. – Further Particulars, Empire (Sydney), 17 May 1865, page 5.

- Reward for Bravery, Sydney Morning Herald, 2 December 1875, page 5.

- Sources

- MacAlister (Snr.), Charles (1907). Old Pioneering Days in the Sunny South. Goulburn NSW: Chas. MacAlister Book Publication Committee.

- White, Charles (1892). Early Australian History: The Story of the Bushrangers, part IV. Bathurst NSW: C. & G. S. White.

- White, Charles (1900). History of Australian Bushranging, Volume I. Sydney NSW: Angus and Robertson. ISBN 0-85550-496-X.

- White, Charles (1903). History of Australian Bushranging: 1863-1880, Ben Hall to the Kelly Gang. Sydney NSW: Angus and Robertson.

- John Vane and Charles White (editor) (1908), John Vane, Bushranger, Sydney: N.S.W. Bookstall Co.

External links

- Patrick William Marony (1858-1939) Bushrangers attacking Goimbla Station, an oil painting (1894) kept in the National Library of Australia.

- Patrick William Marony (1858-1939) Bourke (i.e. Burke) ; Ben Hall ; Frank Gardiner, King of the Road; Gilbert; Dunne (i.e. Dunn) , an oil painting (1894) of the gang members (1894), kept in the National Library of Australia.