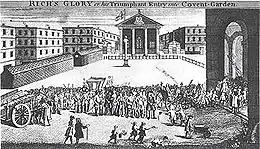

John Rich (producer)

John Rich (1692–1761) was an important director and theatre manager in 18th-century London. He opened The New Theatre at Lincoln's Inn Fields in 1714, which he managed until he built the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden in 1732. He managed Covent Garden until 1761, putting on ever more lavish productions. He popularised pantomime on the English stage and played a dancing and mute Harlequin himself from 1717 to 1760 under the stage name of "Lun."[1][2] Rich's version of the servant character, Arlecchino, moved away from the poor, dishevelled, loud, and crude character, to a colourfully-dressed, silent Harlequin, performing fanciful tricks, dances and magic.[3] Rich's decision to be a silent character was influenced by his unappealing voice, of which he was well aware,[2] and the British idea of the Harlequin character was heavily inspired by Rich's performances.

Biography

Rich as theatre manager

The exact date of John Rich's birth has not been established. He was baptised on 19 May 1692 at St Andrew, Holborn, the eldest son of the theatre manager Christopher Rich, who died on 4 November 1714, and his wife Sarah (née Bewley).

Christopher Rich left his eldest son three-quarters of his share in the Lincoln's Inn Fields theatre, and its associated patent, in his will.[4][5] John Rich's younger brother, Christopher Mosyer Rich (1693-1774) received the remaining quarter. At that time, the theatre was still under re-construction,[6] and performances did not start until 14 December 1714. The two brothers undertook the management of the theatre together at the outset but, over the years, Christopher Mosyer gradually withdrew from active involvement.[4]

Rich's theatre came to specialize in what contemporaries called "spectacle." Today we might call them "special effects." His stagings would endeavour to present actual cannon shots, animals, and multiple illusions of battle. In particular, John Rich exaggerated the theatricality of the Restoration spectacular by creating a new form of hireling drama designed strictly to generate opulent stagecraft. Rich's work was heavily criticized by some, with open letters being published, accusing his work of causing decay in the culture and morality of the stage.[7]

When Alexander Pope wrote the first version of The Dunciad, and even more in the second and third editions, Rich appears as a prime symptom of the disease of the age and debasement of taste. In his Dunciad Variorum of 1732, he makes John Rich the angel of the goddess Dulness:

Immortal Rich! how calm he sits at ease

Mid snows of paper, and fierce hail of pease;

And proud his mistress' orders to perform,

Rides in the whirlwind, and directs the storm." (III l. 257–260)

During his time as producer and director, Rich had multiple battles with his rival managers, including Colley Cibber. Pope summarizes the battle between Cibber's Drury Lane and Rich's Lincoln's Inn Fields as,

"Here shouts all Drury, there all Lincoln's-Inn;

Contending Theatres our (Dulness's) empire raise,

Alike their labours, and alike their praise."

1728 was the year that Rich produced John Gay's The Beggar's Opera.[6] The play ran so successfully, with 62 performances, that it was famously said the play "made Gay rich and Rich gay."[5] John Gay was a long-time friend of Pope's and a frequent collaborator of his.

A couple of years after the success of The Beggar's Opera, Rich moved his company from Lincoln's Inn Fields to a new theatre in Covent Garden.[1][8] It is still a common misconception that Rich built Covent Garden Theatre with the profits from The Beggar's Opera. The true facts have been readily available since at least 1906, when Henry Saxe Wyndham's history of the theatre was published.[9] Rich did what any entrepreneur might do - he advertised for investors, raised the money, and with it built the theatre. A complete paper-trail showing these events still exists: a copy of his Proposals, which all the prospective investors signed, is in the British Library.[10] The subsequent share allocation for each investor is entered in the Middlesex Deeds Register at the London Metropolitan Archives, and the records of Hoare’s Bank in Fleet Street show when the money was received. These facts can now be found elsewhere, in a variety of sources,[4][11] and show that the profits from The Beggar’s Opera were not involved in any way. The Survey of London even includes an Appendix giving the names of all the investors.[12] Rich's theatre opened in 1732 and was the first of three theatres on the site, now known as the Royal Opera House. Rich commissioned some of the great landscape artists of his day to paint scenery for the Theatre, including George Lambert.[6]

Rich's Lincoln's Inn, and then Covent Garden, theatres were in competition throughout his lifetime with Cibber's Drury Lane. Indeed, the two theatres twice put on the same play on the same night, with Romeo and Juliet and King Lear in 1756–57. Rich's company also staged a number of Shakespearean plays that are rarely seen today, among them Cymbeline. In Cibber's Apology, he blames the degradation and skyrocketing costs of play productions on Rich. The general opinion of satirists was that Cibber was thoroughly as guilty as Rich.

Though he may have been portrayed poorly by his rivals, Rich earned a reputation for being a good manager among other players, for good business practices, as well as supporting actors who had left the stage.[6]

Around 1735, John Rich founded the Beefsteak Club along with his scenic artist, George Lambert, that met on Saturdays at a room in Covent Garden theatre.[4][6]

Rich as performer

Rich began his work as "Lun" the Harlequin character in 1717, wearing a leotard with diamond-shaped patches and a mask, encouraging the silence that became normal for the pantomime character.[2] By 1728, Rich was synonymous with lavish (and successful) productions. He performed multiple roles as the "Harlequin" character while the Manager at Lincoln's Inn Fields, including Harlequin Doctor Faustus.[3][6] He was praised for his movement style, allowing each limb to tell a story, such as in Harlequin Sorcerer where he portrayed the harlequin being hatched from an egg.[1][7] According to Soame Jenyns in The Art of Dancing,[13] Rich was a fine dancer, noted for his elevation:

That Pindar Rich despises Vulgar Roads,

And soars an Eagle’s height among the Clouds,

Whilst humbler Dancers, fearful how they climb,

But buzz below amidst the flow’ry Thyme:

Now soft and slow he bends the circling Round,

Now rises high upon the spritely Bound,

Now springs aloft, too swift for Mortal sight,

Now falls unhurt from some stupendous Height;

Like Proteus, in a thousand Forms is seen,

Sometimes a God, sometimes an Harlequin.

After Rich's death, pantomime was criticized for losing the artistry he exhibited with his performances, relying instead more on spectacle and choral numbers.[3] It wasn't until after his death, that many of his rivals, David Garrick included, would recognize his work. Garrick even said his pantomime performances were unmatched in his time.[5]

Private life

John Rich married Henrietta Brerewood on 7 February 1717 at St Clement Danes; they had a son who died in infancy. Henrietta died in September 1725, and Rich then formed a relationship with one of the actresses in his company, Amy Smithies. Her name is quoted in the dispute over the delay in finalising probate on Rich's will in 1779.[14] They had four daughters who survived into adulthood: Henrietta (1727), Charlotte (c.1727?), Mary (1730) and Sarah (1733). Rich considered them to be his legitimate children, although no marriage has yet been found. Amy died in November 1737, and was buried as 'Amie, wife of Mr J Rich' on 1st December in the family tomb in Hillingdon. During this period Rich also sired two children with another of his actresses, Ann Benson - Charles Rich was born in 1729, but nothing further is known about him; and he was followed by Catherine Benson c.1730. Rich acknowledged Catherine as his 'natural daughter' in his will, and left her a bequest. Finally, in 1744, Rich married Priscilla Wilford, who used the stage name, Mrs Stevens. She survived him, and Rich's estate was eventually distributed equally between her and the four daughters.[4]

Rich's niece, by Priscilla Wilford, was Mary Bulkley, who trained and performed at Covent Garden Theatre during his lifetime.[15]

Notes

- "John Rich – Harlequin in England". Archived from the original on 2 July 2007. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), PeoplePlayUK Theatre Museum, retrieved 2 July 2007 - Grantham, Barry (2001). Playing Commedia. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. ISBN 0-325-00346-7.

- Wilson, Matthew R. (2015). The Rutledge Companion to Commedia dell'Arte. New York: Routledge. pp. 359–60. ISBN 978-0-415-74506-2.

- Jenkins Terry:John Rich: the man who built Covent Garden Theatre (Bramber, Barn End Press, 2016)

- "John Rich | British theatrical manager and actor". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- "Londoners of Note: John Rich, Pioneer of Panto". London Historians' Blog. 7 December 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- Smith, Winifred (1964). The Commedia dell'Arte. New York: Benjamin Blom, Inc. p. 147.

- "Rich, John". factmonster.com. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- Saxe Wyndham, Henry: The Annals of Covent Garden Theatre from 1732 to 1897 (London, Chatto & Windus, 1906), vol. 1, pp. 20-26.

- British Library: Add MS 32428. Original list of share-holders in Covent Garden Theatre, on its being built by John Rich in 1731.

- Hume, Robert D: "John Rich as Manager & Entrepreneur”. The Stage’s Glory, John Rich (1692-1761) edited by Berta Joncus & Jeremy Barlow, (Delaware U.P., 2011) pp. 40-41.

- Covent Garden Theatre and the Royal Opera House: Management, in Survey of London: Vol. 35, the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, and the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, ed. F H W Sheppard (London, 1970), pp. 71-85, and Appendix, pp. 109-111.

- Jenyns, Soame: The Art of Dancing: A Poem, in Three Canto's (W.P. and sold by J. Roberts, 1729), pp. 28-9.

- The National Archives: C 12/1056/10: Bencraft v. Rich

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: Bulkley née Wilford; other married name Barresford, Mary, by John Levitt

References

- . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.