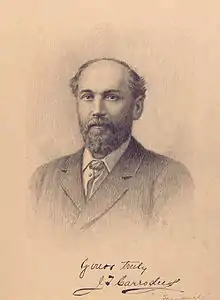

John Tiplady Carrodus

John Tiplady Carrodus (1836–1895) was an English violinist.

Life

Carrodus was born on 20 January 1836, at Keighley, in the West Riding of Yorkshire. He took violin lessons from his father Thomas Carrodus, who was a barber and music-seller.[1] He made his first appearance as a violinist at the age of nine, and before the London public four years later.[2] He had the advantage of studying between the ages of twelve and eighteen at Stuttgart, with Bernhard Molique.[3][2] He also “ became a 'follower of Spohr', who expressed his admiration for the Englishman's playing.”[4]

On his return to Britain in 1853 Sir Michael Costa got him engagements in the leading orchestras. He was a member of the Covent Garden opera orchestra from 1855.[5] He made his debut as a solo player at a concert given on 22 April 1863 by the Musical Society of London, and succeeded Prosper Sainton as leader at Covent Garden in 1869. He led the Covent Garden orchestra for twenty-five years.[6] He also took over from Sainton as the Leader of the Three Choirs Festival orchestra in 1882.[2]

He taught at the National Training School of Music, the Croydon Conservatoire of Music, the Guildhall School of Music, the Royal Academy of Music, and Trinity College, London. He has the distinction of being the first president of the College of Violinists.[4][5][6] He was an early proponent of the violin recital.[5] His concert at St James's Hall on 20 January 1881, which included the works of Molique and Spohr, is “widely recognized as the first public violin recital.”[4]

For many years, Carrodus had led the orchestra of the Philharmonic Society[2][7] and those of the great provincial festivals. The coveted Carrodus violin, made by Guarneri in 1743, was said to have belonged to Carrodus.

Carrodus was constantly striving "for improving the standard of string playing in English orchestras." He was famous for setting extremely high standards in his own playing and in that of his pupils.[8] Lilian Baylis was one of his notable students. He taught her violin at the Royal Academy of Music.[6]

In addition to editions of the treatises of Loder and Spohr, Carrodus published his own “Chats to violin students on how to study the violin.” [4] He published two violin solos and a Morceau de salon, and was a very successful teacher.[3] [9] He edited a popular six-volume edition of violin duets for Pitman's Sixpenny Musical Library.[1]

He died at Hampstead, London on 13 July 1895[3] and was buried in a family grave on the eastern side of Highgate Cemetery.

References

- Orel, Harold (3 December 1996). The Brontës: Interviews and Recollections. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-877-45537-0. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- Boden, Anthony (16 June 2017). The Three Choirs Festival: A History. Woodbridge, Suffolk, England: Boydell & Brewer. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-783-27209-9. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- Chisholm 1911.

- Golby, David (17 June 2016). Instrumental Teaching in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Oxon: Routledge. p. 205. ISBN 978-1-317-22072-5. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- Katz, Mark (9 February 2006). The Violin: A Research and Information Guide. Oxon: Routledge. p. 302. ISBN 978-1-135-57696-7. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- Gilbert, Susie (3 March 2011). Opera for Everybody: The Story of English National Opera. London: Faber & Faber. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-571-26865-8. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- Birkin, Kenneth (7 July 2011). Hans Von Bülow: A Life for Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 260. ISBN 978-1-107-00586-0. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- Schafer, Elizabeth (1 October 2007). Lilian Baylis: A Biography. Hatfield, United Kingdom: University of Hertfordshire Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-902-80664-8. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- Zon, Bennett (29 April 2016). Music and Performance Culture in Nineteenth-Century Britain: Essays in Honour of Nicholas Temperley. Oxon: Routledge. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-317-09238-4. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Carrodus, John Tiplady". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 409.