John Witt Randall

John Witt Randall (November 6, 1813 – January 25, 1892)[1][2] was a minor poet and, for a brief time, a naturalist, but is best known for the collection of drawings and engravings that he bequeathed to Harvard University.

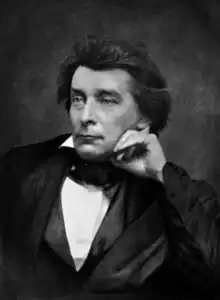

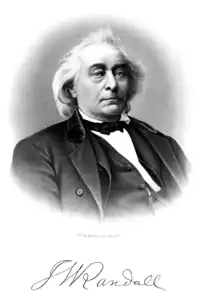

John Witt Randall | |

|---|---|

John Witt Randall, age 40 | |

| Born | November 6, 1813 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | January 25, 1892 (aged 78) Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Occupation | Poet, art collector, and naturalist |

| Alma mater | Boston Latin School, Harvard University |

| Period | 1834–1892 |

| Literary movement | Romanticism |

| Notable works | Consolations of Solitude (1856) |

Early life

Randall was born in Boston, the son of Dr. John Randall (1774–1843), and his wife, Elizabeth Wells Randall (1783–1868). Dr. Randall was an eminent physician and dentist, with three degrees from Harvard College (A.B. 1802, M.B. 1806, M.D. 1811),[3] and Elizabeth Randall was a granddaughter of the American Founding Father Samuel Adams.[4] After they married in 1809, John and Elizabeth Randall lived at 5 Winter Street, a wood-framed house with a garden on the southeast corner of Winter Street at Winter Place (the home, from 1784 until his death in 1803, of Samuel Adams and, until her death in 1808, of his widow Elizabeth Adams).[5] Around 1830, Adams' old house was replaced by Dr. Randall's new one, and the address changed to 20 Winter Street.[6] The family lived there until Dr. Randall's death in 1843.

Notwithstanding his Boston residency, Randall retained an attachment to his family's farm in Stow, Massachusetts, on which he grew up. The success of his medical practice allowed him to buy his siblings' interest in the property, after which "he built a new and more comfortable dwelling-house near the site of the original homestead, which had fallen into decay; and it became a cherished summer resort for him and his family."[7]

An only son, John Witt Randall grew up with four sisters: Elizabeth Wells Randall (1811–1867),[8] Belinda Lull Randall (1816–1897), Maria Hayward Randall (1820–1842), and Hanna Adams Randall (1824–1862) who later changed her name to Anna Checkley Randall.[9][10]

Education and brief career in natural history

Randall prepared for college at Mr. Green's school in Jamaica Plain,[11] and at the Boston Latin School, after which he entered Harvard College, graduating in the class of 1834. Compelled by his father to study medicine, he graduated from the Harvard Medical School (M.D., 1839), but never practiced.

At Boston Latin and Harvard, Randall was considered eccentric. Thomas Cushing, a contemporary who attended both schools with Randall, wrote that "his peculiar and marked originality of character is well remembered [by his classmates]. Though among them, he was not wholly of them, but seemed to have thoughts, pursuits and aspirations to which they were strangers." Cushing recalled how Randall formed an interest in natural science while at Harvard:

His tastes developed in a scientific direction, entomology being the branch to which he devoted himself. The college at that time did little to encourage such pursuits, but he pursued the even tenor of his way till he had made a very fine collection of insects, and extensive and thorough knowledge on that and kindred subjects, while his taste for poetry and the belles-lettres was also highly cultivated.[12]

In 1836, while a student at the Harvard Medical School, Randall accepted an appointment as consulting Zoologist to the United States Exploring Expedition, organized to explore and survey the Pacific Ocean, but resigned before the expedition set to sea in August 1838. In an 1892 obituary notice, one scientific journal noted that Randall was known "to the present generation of entomologists as the author of two papers descriptive of the Coleptera of Maine and Massachusetts published more than fifty years ago in the second volume of the Boston journal of natural history.” (See bibliography below.)

Randall's Harvard classmate Henry Blanchard, wrote that Randall was "a very learned man, and in natural science distinguished...had he been allowed by his father to follow his inclination, I have little doubt he would have been a distinguished man — distinguished as a scientist, a more useful and happier man. His father was determined he should adopt medicine as a profession. The son might have enjoyed it as a study, but the practice of it as a pursuit would have been abhorrent.[13]

Later life

According to Randall's friend and literary executor, Francis Ellingwood Abbot, Randall's "whole boyhood and youth had been embittered by unhappy relations with his father" for "Dr. John Randall was a man of iron will, disguised to the world by great suavity and polish of manner, but manifested to his family in a despotic and often capricious arbitrariness that brought much misery to those whom, doubtless, he sincerely loved." After Dr. Randall's death in 1843, "the son lived on, educated for a professional career he abhorred, diverted from the scientific and literary career he desired, and driven into a seclusion from the world which his early companions beheld in dull, uncomprehending wonder.”[14]

After his father's death, Randall inherited his father's estate and thenceforth, wrote Abbot, "passed his life in leisure and retirement from the world," nurturing his family's property on behalf of his mother and sisters, expanding and developing the house and grounds at Stow, and indulging his taste for literature and the fine arts. Between 1843 and the outbreak of the Civil War, he accumulated a collection of some 575 drawings and 15,000 etchings and engravings, intending to illustrate the whole history of the art.

In an autobiographical sketch written in 1884 for the 50th anniversary of his Harvard Class, Randall summarized his literary accomplishments:

As to my literary works, — if I except scientific papers on subjects long ago abandoned, [such] as one on Crustacea in the Transactions of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia; two on insects in the Transactions of the Boston Society of Natural History; one manuscript volume on the animals and plants of Maine...; Critical notes on Etchers and Engravers, one volume; classification of ditto, one volume, both in manuscript incomplete and not likely to be completed, together with essays and reviews not likely to be published, — my doings reduce themselves to six volumes of poetic works, the first of which was issued in 1856, and reviewed shortly after in the North American, while the others, nearly or partially completed at the outbreak of the civil war, still lie unfinished among the many wrecks of Time, painful to many of us to look back upon, or reflect themselves upon a Future whose skies are as yet obscure.[15]

Death and bequests

_-_H427_-_Harvard_Art_Museums.jpg.webp)

John Witt Randall died a bachelor at Boston on January 25, 1892, at the age of seventy-eight and was buried in Boston's Mt. Auburn Cemetery. His friend Francis Abbot attended the funeral:

On Thursday, January 28th, a small company gathered at the house. The funeral services were conducted by Rev. Dr. Edward Everett Hale, and all that could die of John Witt Randall was laid to rest at Mt. Auburn. Three of us, Miss [Belinda] Randall and Miss O'Reilly and myself,[16] followed him together in one carriage, at her own request, to the family tomb.[17]

During the previous quarter century, Abbot had observed a change in his friend, which he called a "puzzling phenomenon."

...the apparent diversion of a most serious, lofty and unworldly spirit to the accumulation of worldly wealth. By his own ability and indomitable energy, he multiplied the comfortable family inheritance into a great fortune, ten times as large as he found it. From the period of the Civil War, he almost wholly ceased to increase his invaluable art collections, or to take much interest in the writing of poetry...in the winters, I found him, when I entered his study, bending grimly over a vast mass of maps, railroad reports, statistical tables, and business documents of all sorts. He was studying out for himself, at first hand, the foundations and elements and necessary conditions of all that vast activity in railroad development which in a generation created a new America.

He prepared no will, and his estate passed to his only surviving sibling, Belinda Lull Randall, to whom he entrusted its final disposition. She made many bequests, executed both before and after her death in 1897. Among her beneficiaries were Harvard University, the town of Stow, and many charitable institutions.[18]

In April 1892, she created a $500,000 trust fund to be used "for charitable purposes," to be known as the J.W. Randall Fund, and in May the Treasurer of Harvard University reported that, in accordance with her brother's wishes, she "had given to the college his large collection of engravings, gathered by him to illustrate the history of the art of engraving: also the sum of $30,000 to establish the John Witt Randall Fund, the income of which is to be used so far as it may be needed for the care and preservation of his engravings..."[19]

That same year she made a gift of $55,000 to the town of Stow, $20,000 for general purposes, $10,000 for poor relief, and $25,000 for the construction of a library building, which was built in 1893 and dedicated in February 1894 as the Randall Library. The new building was initially furnished with 700 books donated to the town by John Randall from his private library.[20]

In 1897, the Randall Fund gave Harvard University a large sum, including $10,000 for the construction of a new dining hall (Randall Hall, completed in 1898), a "further $10,000 toward the Phillips Brooks House, and a liberal endowment to Radcliffe."[21]

Bibliography

Writing on natural history

- John Witt Randall. "Description of new species of coleopterous insects inhabiting the state of Maine," in the Boston Journal of Natural History, February 1838, vol.2, no.1, pages 1-33.

- John Witt Randall. "Description of new species of coleopterous insects inhabiting the state of Massachusetts," in the Boston Journal of Natural History, February 1838, vol.2, no.1, pages 34–52.

- John Witt Randall. "Catalogue of the crustacea brought by Thomas Nuttall and J.K. Townsend from the west coast of North America and the Sandwich Islands, with descriptions of such species as are apparently new, among which are included several species of different localities previously existing in the collection of the Academy," in the Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 1839, vol. viii, Pages 106–147.

Poetry

- John Witt Randall. Consolations of Solitude (Boston: John P. Hewitt, 1856).

- John Witt Randall (author), Francis Ellingwood Abbot (editor). An Early Scene Revisited: A Poem (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson & Son, University Press, 1894).

- John Witt Randall (author), Francis Ellingwood Abbot (editor), with illustrations by Francis Gilbert Attwood. The Fairies' Festival (Boston: Joseph Knight Co., 1895).

- John Witt Randall (author), Francis Ellingwood Abbot (editor). Poems of Nature and Life (Boston: George H. Ellis, 1899).

Publications about Randall

- A.G.R. Hale. John Witt Randall (Stow, MA: Stow Historical Society, 1892).

- "John Witt Randall," in Psyche, A Journal of Entomology, September 1892, page 316.

- Sarah Vure, Fogg Art Museum. The John Witt Randall Collection (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Art Museums, 1998).

See also

- Anna Maria Wells, poet, wife of Randall's uncle Thomas Wells

- Frederick A. Wells, politician, Randall's first cousin once removed

- Webster Wells, mathematician, Randall's first cousin once removed

- Joseph Morrill Wells, architect, Randall's first cousin once removed

References

- The earliest source for his date of birth is: Thomas Cushing, Memorials of the Class of 1834 (Boston: David Clapp & Son, 1884), page 83-84.

- For his date of death see: "Massachusetts Deaths, 1841-1915, 1921-1924," database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:N7PH-3C7 : 2 March 2021), John W. Randall, 25 Jan 1892; citing Boston, Suffolk, Massachusetts, v 429 p 43, State Archives, Boston; FHL microfilm 961,508.

- Quinquennial Catalogue of the Officers and Graduates of Harvard University (Cambridge MA: Harvard University, 1910), page 169.

- "John Witt Randall" (PDF). Psyche. 6 (197): 316–317. 1892. doi:10.1155/1892/61412.

- The date of purchase, the location and description of the house are found in: William V. Wells. The Life and Public Services of Samuel Adams (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1865), vol. iii, pages 332-333.

- In 1807, the bachelor Dr. Randall lived at 5 Winter Street, possibly as Mrs. Adams' tenant. By this proximity he may have met Mrs. Adams' step-daughter Elizabeth Wells.

- Abbot, "The Randall Family, p. 42.

- Elizabeth Wells Randall married in 1836 Alfred Cumming, the governor of the Utah Territory from 1857 to 1861.

- Descendants of John Adams, Samuel Adams, Josiah Bartlett, and Carter Braxton, Signers of the Declaration of Independence, Collections of the Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia (not dated), p.48.

- Francis Ellingwood Abbot, "The Randall Family" in John Witt Randall's Poems of Nature and Life (Boston: George H. Ellis, 1899), pp. 41-42.

- John Witt Randall (edited by Francis Ellingwood Abbot, with illustrations by Francis Gilbert Attwood), The Fairies' Festival (Boston: Joseph Knight Co., 1895).

- Thomas Cushing. "Notices of the Survivors," in Memorials of the Class of 1834, Harvard College (Boston: David Clapp & Son, 1884) page 84.

- Abbot, "The Randall Family," p. 54.

- Abbot, "The Randall Family," pp. 60-61.

- Thomas Cushing. "Notices of the Survivors," in Memorials of the Class of 1834, Harvard College (Boston: David Clapp & Son, 1884) pages 85-86.

- “Miss O’Reilly” cannot refer to the Randall’s first cousin, Catherine Hall Wells O’Reilly, as she died in 1891, but probably refers to O'Reilly's step-daughter, Mary Jane O’Reilly (1836–1915), to whom Belinda Randall willed all her property in Stow. Mary Jane Reilly's grandmother was Marysylvia Randall Whitcomb, Belinda Randall's aunt.

- Abbot, "The Randall Family," p. 219."

- Abbot, "The Randall Family," pp. 209-210.

- Justin Winsor, editor. Harvard University Bulletin, No. 53, 1892, page 2.

- "About the Library | Stow MA".

- "Recent Bequests," in The Harvard Crimson, September 29, 1897.

External links

- John Witt Randall (1856). Consolations of Solitude. Jewett.